I met John Robinson for the first time in a quiet bar in Campo Santo Stefano, Venice. It’s the eve of his solo show, and around us unfold the usual conversations: final setup details, deadlines, curatorial notes. But he withdraws from that ordinary current of words and, with a gesture that feels almost sacred in its stillness, slips silently out of the linear time of anticipation and into the territory of confession.

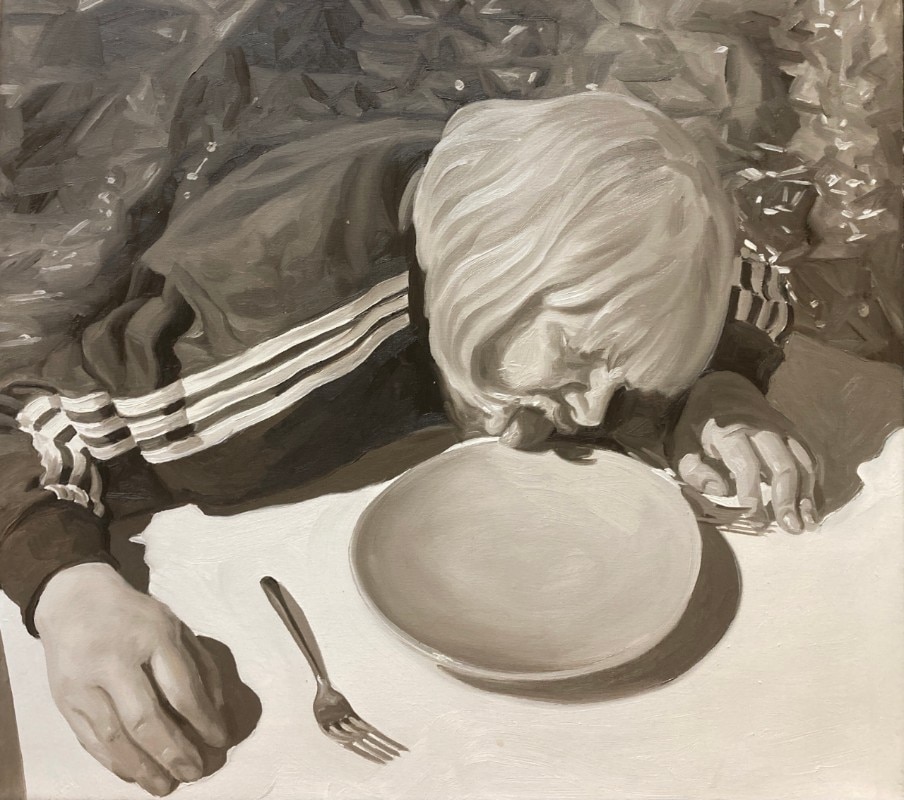

He begins to tell me his story: he says he was raised within a Christian cult, a radical religious movement that emerged in nineteenth-century England. He left it at the age of seventeen. He recounts this with a surprising calmness, almost detached. There’s no pathos, no dramatic emphasis – just a clarity that unsettles. He speaks as though the events no longer concern him, as though they belonged to another biography. It’s no coincidence that each of his paintings is a literal depiction of a real event, restaged through collective performance. Every painting, in fact, emerges from performance – a ritual in which the artist reenacts true episodes, reconstructed and documented. The painting comes after, as synthesis, as material echo, as reckoning.

In the following days, at the 10 & ZERO UNO gallery, I finally see him in action. The space is intimate, and at its center stands The Shed: a wooden structure transported from his garden in Worcester and rebuilt inside the gallery. Within its narrow confines, Robinson performs a tarot reading – using a deck he has illustrated himself. The cards depict distorted, dreamlike figures, ambiguous bodies, symbols that seem to surface from a collective, archetypal unconscious.

Robinson is a grown man with a powerful build, yet within the two square meters of The Shed, he appears more like a child. The space feels less like a shed and more like a shield. The artist exposes himself, though not to seek attention. Rather, he becomes the child attempting to reckon with his own story – reflected in those who sit before him to have their cards read. What takes center stage is not him, but memory – trauma, specifically – which unites past and present in a single, uninterrupted instant. And painting, again, acts as a form of expiation, a gesture of catharsis. There's also the notion of the limit, both physical and temporal: drawn by the architectural boundaries of the shed, but also by the symbolic threshold of what the artist – and the man – can bear.

There is a frontier here, one worth probing: the line between what can still be endured and what cannot. When does belief dissolve? When does one abandon an identity? And what remains after? Robinson also navigates the delicate knot between vulnerability and power, between faith and manipulation. This time, it is he who assumes the role of prophet and seer – a reversal of the position once held over him.

He had told me, with a tone that was both grave and lucid, that the next day’s performance would be “something terrible to witness.” He looks me straight in the eye and says, “I don’t even know why I’m doing this.” But it’s not the voice of someone hesitant or disengaged. It’s the voice of someone moved by an impulse so primal, so uncontrollable, it overrides reason. In that sentence lies a quiet desperation – but also something fiercely alive. It is the same energy that makes art possible.

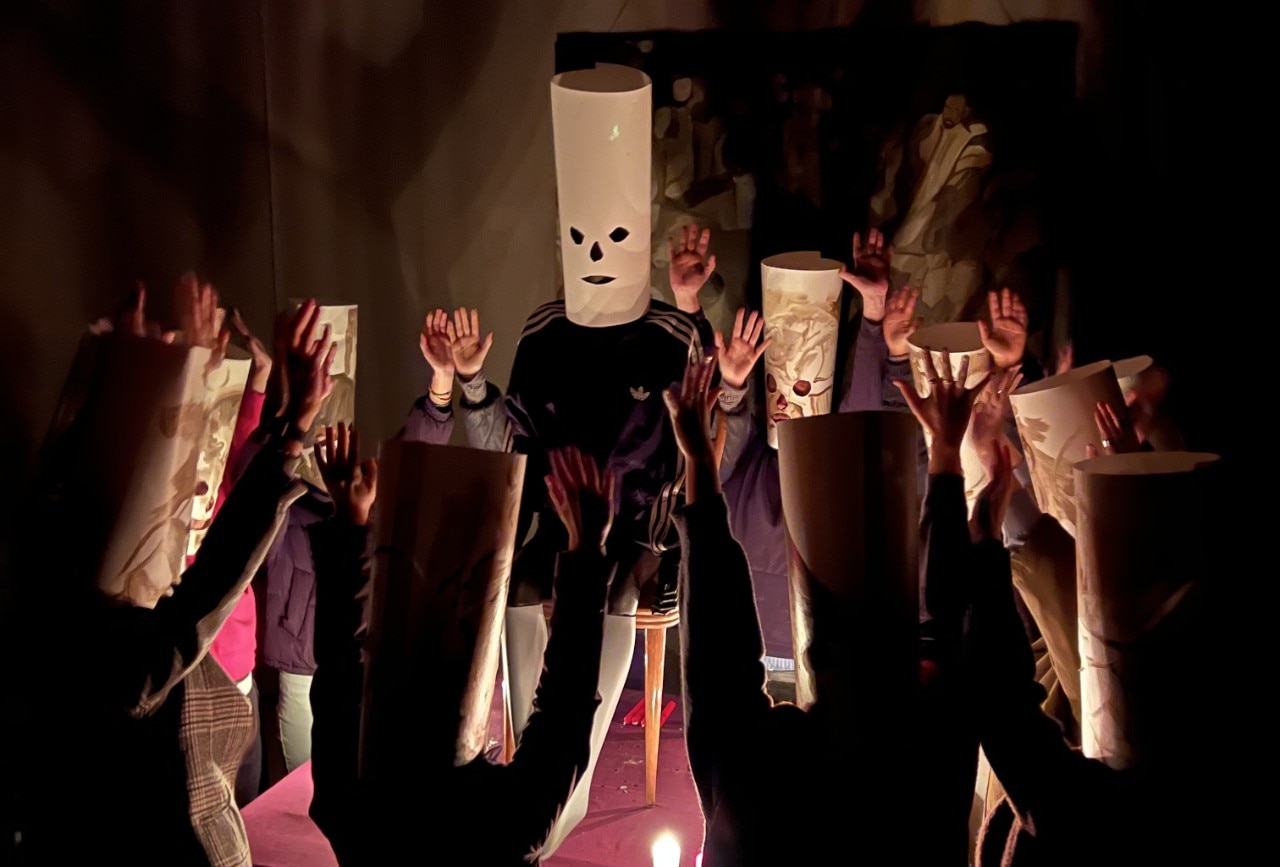

The second performance is a disturbing, visceral re-enactment of a childhood birthday. A party reconstructed in raw, almost violent terms. Inside the shed, the participants wear masks bearing the artist’s face. Robinson celebrates alone, surrounded by multiplied versions of himself, chewing on torn wrapping paper, burying his face in the food. Humiliation becomes the axis. But it’s not just the artist’s own – nor only that of his inner child – it’s also the viewer’s.

To take part in Robinson’s work is to enter a zone of instability. His practice touches on the fear of exposure, the weight of memory, the body as a site of both shame and resistance. Ultimately, painting becomes a way to hold onto what has happened – not to fix it, but to prevent it from vanishing entirely. The Shed remains open to visitors until July 19.