The German word “Heimat” dates back to the 11th century and carries a broader meaning than the English “home” (or the German “heim”). Not only it signifies “home” but also “homeland.”

The “Heimat” that artist Sandra Knecht brings to the KBH.G gallery in Basel is a mosaic of photographs – a selection from the over 20,000 images from her decade-long project My land is your land, images she has shared on her Facebook account. It includes a dismantled Swiss bee house (“It was too tall to fit in here,” explains Raphael Suter, the foundation’s director), its roof adorning the entrance hall while the house itself occupies the main exhibition space. Nearby stands a striking bronze sculpture, a metamorphosis of a pear tree trunk, a homage to a tree that holds deep personal significance for Knecht, as seen on her Instagram profile; and then, scattered across the floor, there are a series of objects: mummified animal bodies, including snakes, cats, and a raven staring at you.

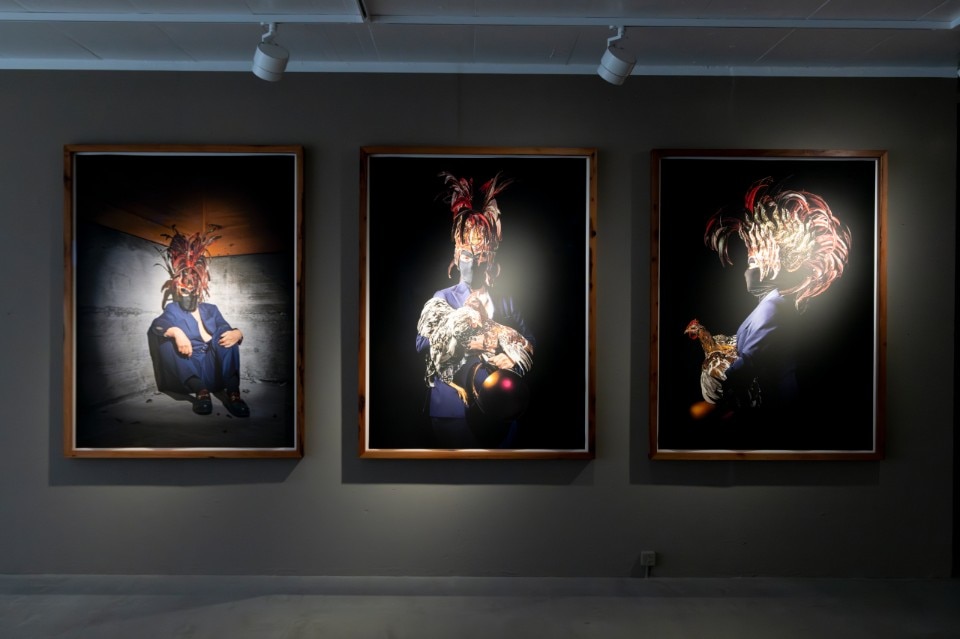

“There are eyes watching you here,” Sandra Knecht tells me. Her concept of home defies the illuminist concept of architectural designs, the pristine aesthetic of renderings, or “Instagrammable” interiors seen in Domus. Instead, it’s a restless place – “a foreign place, an unstable place,” as the exhibition brochure describes. It’s a place that is also a body, that is inhabited by spirits, by “djinns.” The “twilight archetypes” are the focus of the artist’s attention, the attraction point of her “Home is a foreign place.”

What house is this?

The exhibition features Knecht’s collection of vinyl records, mostly from her youth, displayed alongside a record player and two speakers. It’s silent. It’s here that I meet Sandra Knecht, dressed in sweatpants – whose font suggests it belongs to some metal band – and Nike sweatpants, fiddling with the sound system that doesn’t work. One of her Chihuahuas, Lupita, circles around her. I wonder if it’s a performance. For Knecht, music is essential; she often DJs, director Suter explains. In addition to the critical essays and a selection of photographs, there’s the exhibition’s companion volume – given for free to all visitors – which includes QR codes to Knecht’s playlists. Lupita the Chihuahua approaches me, her cartoonishly expressive sweet eyes fixed on me.

Sandra Knecht hasn’t always been an artist by passion. She worked as a social worker for over 20 years before entering the visual arts in 2011, well into her thirties. She participated in the Venice Biennale in 2017 and won the prestigious Swiss Art Award in 2022, Switzerland’s highest honor for the arts.

Archetypes in the twilight

Knecht speaks passionately about archetypes, like the rooster – one that is very dear to her – which she reconnected with “during a residency in Mexico where I spent time on horseback with gauchos.” Her work explores Alpine folklore and its masks, from the Tschäggättä and Krampus to the Jodels, and cooking, which is another recurring theme in her art – her Dinner Party series features 20 recipes inspired by 20 iconic female figures, including Patti Smith, Nan Goldin, Audre Lorde, and Ana Mendieta, the Cuban American artist. We talk about this exhibition featuring many pictures, yet the house she creates feels like an evocation, an ethereal structure of shifting lines and ambiguous light, a concept hard to fix. Its queer identity, much like hers, transcends definitions and boundaries. “Home is within you,” she tells me. Though her English is direct and powerful, she expresses self-doubt about it, saying she speaks “like a little kid,” often relying on a translator, an English teacher from Basel who points out to me that the back of the bee house reads in Gothic script: “Willst du Fleiß & Ordnung sehen, musst du zu den Bienen gehen” – “If you want to see diligence and order, you must go to the bees.”

It is said that Cezanne had a visual defect and that this resulted in his painting showing 'the birth of order', as Merleau-Ponty put it. Talking to Knecht, watching her as she moves through the rooms of the exhibition, which I visit when the sun is about to set, when the shadows outside the Foundation lengthen and then everything is swallowed up by darkness, makes me think that she does not see the same things that I see, that we see, it is as if her perception has extra layers, of things that I feel are there but cannot clearly distinguish. She manages to capture all this in her Gesamtkunstwerk. In Knecht’s case, separating the artist from the person seems almost impossible. Her home, her dwelling is in Buus, in Basel’s countryside, where she lives with her partner and a menagerie of animals, including sheep (“sometimes, especially if they are old and sick,” she slaughters one and cooks it) and a turkey named Kurt, admired by famed curator Hans Ulrich Obrist. Animals, nature, folklore, and books are part and parcel of the identity she crafted on her generous Instagram profile – definitely not your typical artist’s feed.

For the opening of “Home is a Foreign Place,” Knecht hosted a group of about 20 journalists and influencers in Buus. “Balenciaga shoes and sheep, imagine that!” she laughs. At the foundation’s opening, she cooked herself – serving sheep sausages, Suter recalls, made from one of her own.

Preserves and self-preservation

At the entrance to the exhibition stands a shelf filled with preserves, a nod to Chnächt, Sandra Knecht's gastronomic project housed in a renovated barn in Basel, open until 2019 – a house that “seemed to fall from the sky.” These are the Heimatgläser – jars of Heimat – first presented at the Venice Biennale. They serve as a metaphor for identity, which, according to Knecht, cannot truly be preserved; at best, it can become a “preserve.” It’s a way of freezing ourselves in time, stored in dark, protected spaces like cellars but always with an expiration date.

On the wall farthest from the Foundation’s entrance – yet strategically positioned to be one of the first things visitors see in the main exhibition room – is a triptych of photographs of Sandra Knecht wearing a headdress shaped like a rooster’s head. It’s actually a helmet, she explains. In a way, these images hold the key to understanding the entire exhibition. “I am a queer woman who grew up in the mountains, in a small town,” she tells me. She says it in German carefully repeating and elaborating on the details – a sign of how deeply personal and fundamental this is to her. In such an environment, she says, “they see you as a drag queen.” The rooster, which appears again in another large photograph in the exhibition, is an archetypal animal for Knecht. It is not merely a costume but a form of armor. “That rooster head is a helmet that protects you.”

- Exhibition:

- Home is a Foreign Place, Sandra Knecht

- Location:

- Kulturstiftung Basel H. Geiger

- Dates:

- Until 27th April 2025