Francesco Zizola probably needs no introduction, but it is here perhaps appropriate to underline how from his degree in Anthropology to his activity as a photojournalist, from the many awards he received to the important works he published, from the foundation of the photographic agency NOOR to the creation of 10b Photography, each step of his career has been moved by the desire to take a new path, to experiment new ways, to test himself and take nothing for granted, even in the solidity of an organic and always recognizable project.

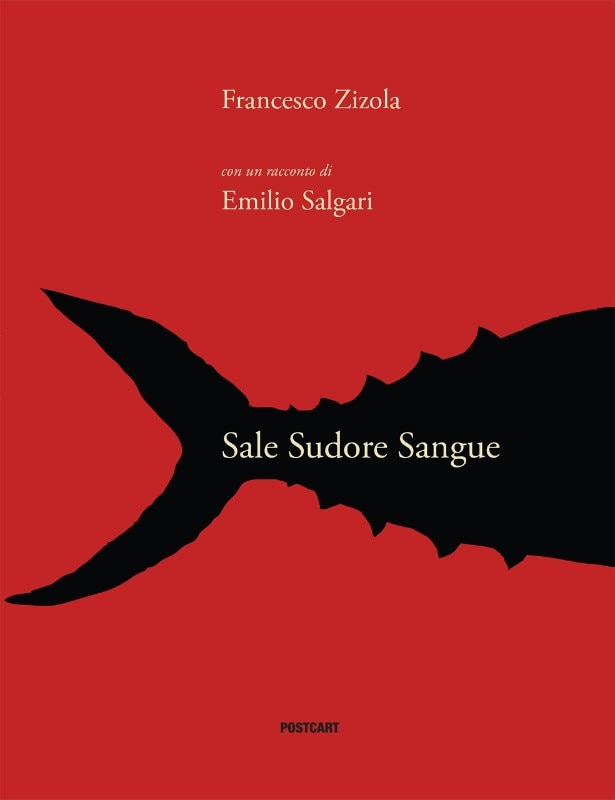

In this sense, his latest book for Postcart Edizioni, Sale Sudore Sangue (Salt Sweat Blood) is both the culmination of a seven–year research project and one of the many possible access points to a broader and more complex reflection: from the traditional fishing of bluefin tuna, carried out for thousands of years in the tuna nets of the Mediterranean, of which only a few examples remain today in Sardinia, to a large and multifaceted fresco on the relationship between man and nature, soon to be published.

On the occasion of the release of Sale Sudore Sangue, Zizola agreed to share with Domus some of the background and reasons that have characterized and led him to this new chapter of his narrative through images, accompanying everything with an ad hoc selection for visitors to our website.

You have been practicing scuba diving since you were 14 years old, so long before becoming a photographer, and the image that led you to undertake this new job was born almost as a souvenir photo, on the wave of emotion, but then won a World Press Photo: where did your passion for the sea and, in particular, your interest in the traditional fishing of bluefin tuna come from?

As with photography, I prefer to define this passion more appropriately as love, which was initially youthful and then became increasingly mature and complex as the decades passed. The sea as a physical reality is an element in which I find a deep part of me while, as a symbolic entity, it is a metaphor for the psychic reality and the complexity of nature. In this sense, the encounter with the millenary reality of bluefin tuna fishing that uses the tuna trap method opened up unprecedented scenarios on both levels.

Sale Sudore Sangue is a title that already says a lot about how your images are direct and yet never immediate. In the book, a certain epic dimension is in fact intertwined with the everyday, a timeless aura overlaps with a story with a contemporary flavor: how did you achieve this synthesis?

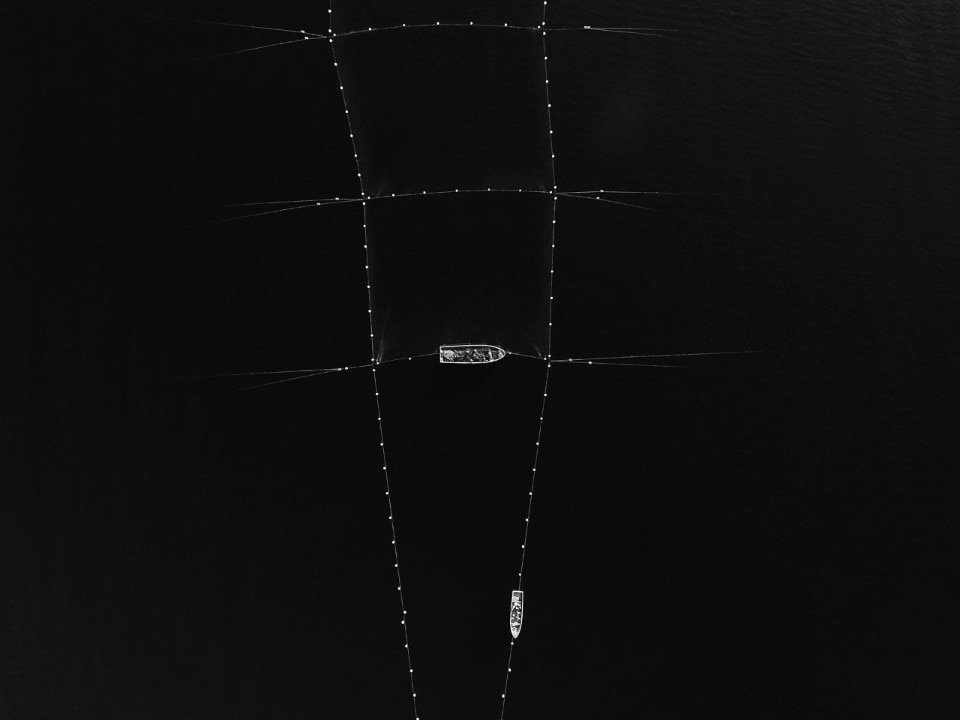

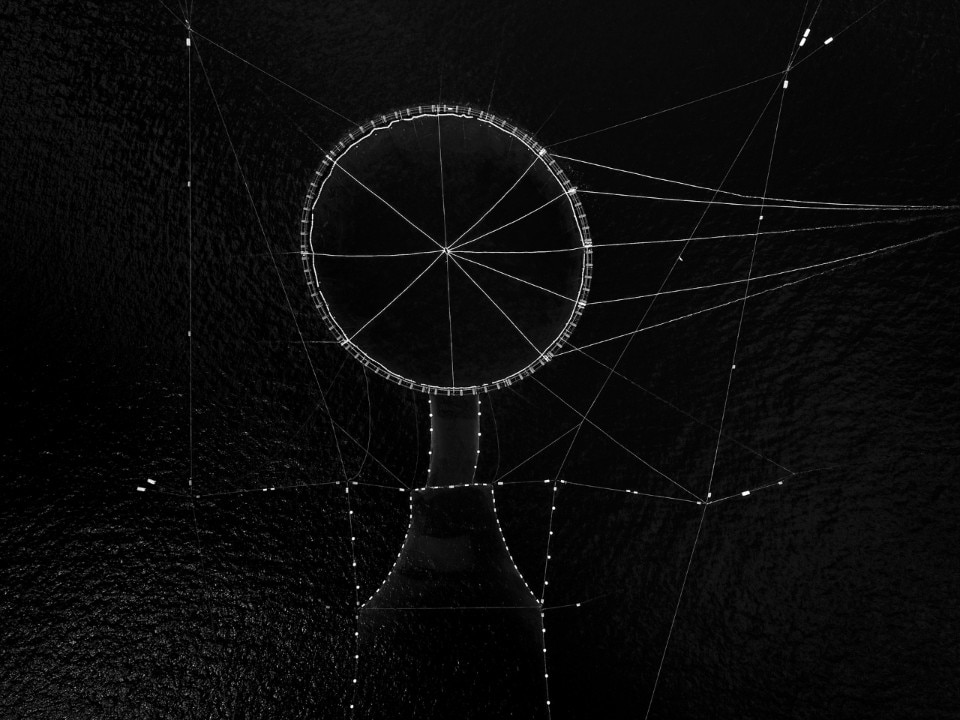

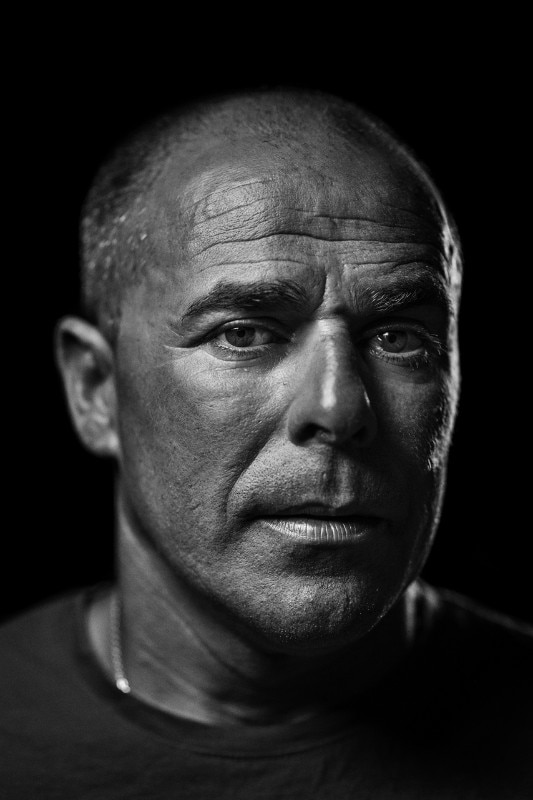

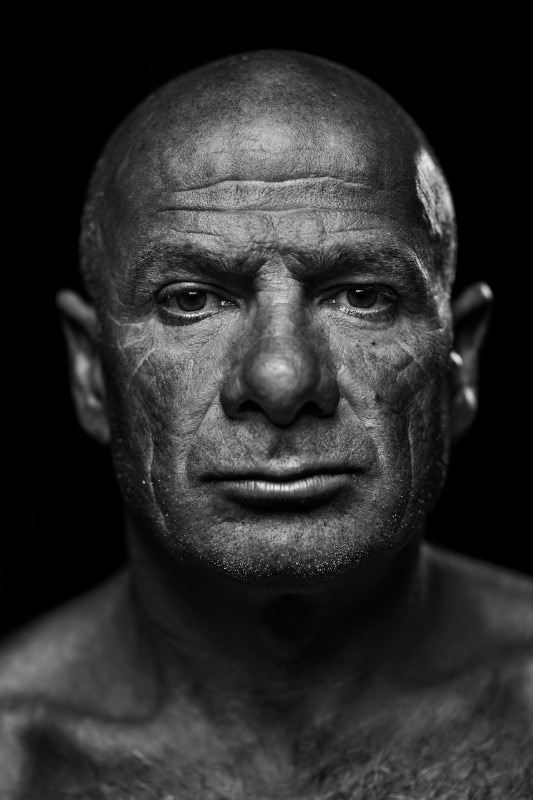

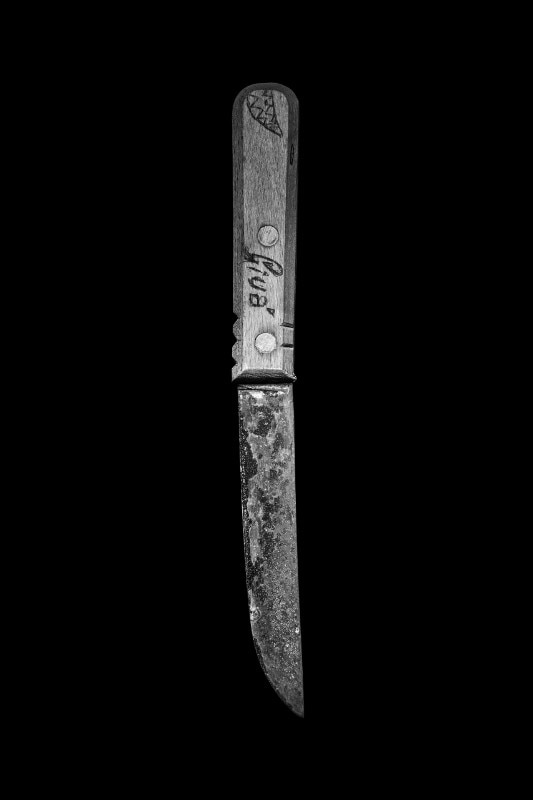

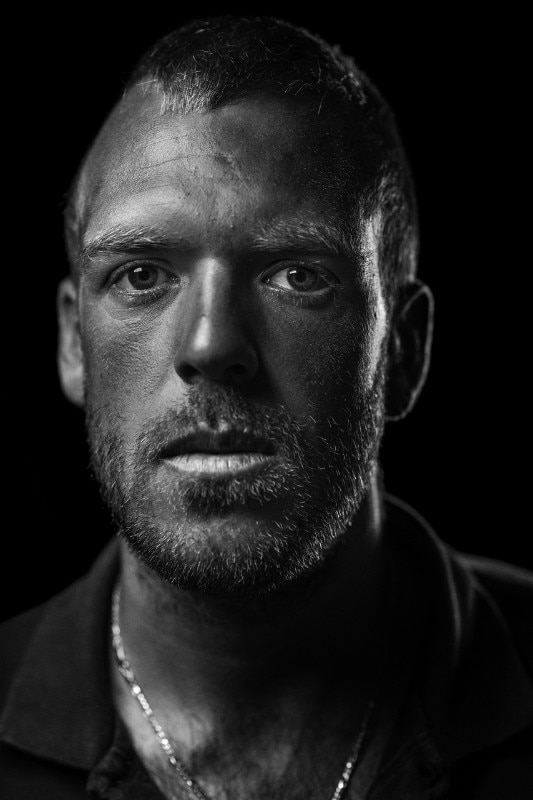

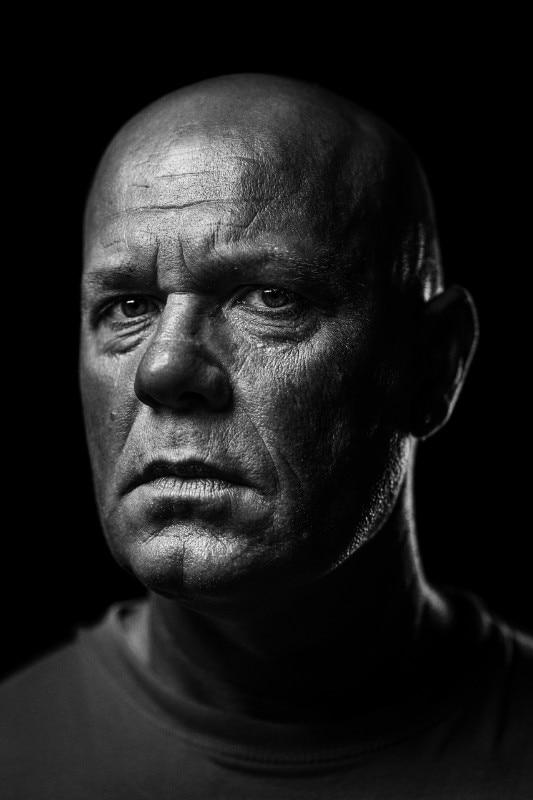

I tried various devices to direct the visual narration of a present reality towards a diachronic perspective. The black and white, with the implicit reference to the past and to the synthetic document, the different perspectives that gave voice, as in a chorus, to the different protagonists of the story (the tuna fish underwater, the fishermen on the boats and finally the seagulls that opportunistically follow the fishing operations from above), the rhythm and the alternation of these subjective visions. I also believe that a significant contribution was made by the decision not to focus on the slaughter, the climax of a complex act of knowledge of nature on the part of this wise community of fishermen, but rather on the relationship between the space of nature and that of the instrument, that is, the tuna trap intended both as a trap and a physical proof of the contrasting and never obvious relationship between man and nature.

In the story that opens the book, perhaps what is most striking is to hear Salgari's true voice, that of a reporter and not that of the famous novelist who set his stories in places he did not know firsthand. It is a rare point of view that represents a bit of a surprise, but also a confirmation of your intentions: where did the idea of publishing it come from?

Salgari's story comes from a little–known publication from the beginning of the twentieth century, which has recently entered the center of the debate on Salgari the storyteller who was often inspired by Sardinian culture and landscape to color his novels and exotic tales of adventure. “La pesca dei tonni” (Fishing for Tuna) is the only story directly related to Sardinia and seems to be the result of a direct experience lived by the writer. It was the beginning of the last century and Salgari interpreted his time, where the dominion of man over nature was a heroic and positive reality. The adventurous epic of the crew of fishermen who, under the command of the Rais, bend until death a large number of mammoth tunas echoes the century in which progress and technology begin to prefigure the alliance towards the unchallenged domination of man and his power over the rest of the living creatures.

After reading it the first time, I was particularly struck by the fact that the fishing told by Salgari was identical to the one I witnessed during the seven years of my project. The only difference was not in the subject matter, but in the way it was told. I wanted to emphasize a reality that is anything but romantic or heroic, even if it is still positive. The fishermen I have portrayed are men who still know the wise art of drawing survival from nature without compromising it, and therefore declining to the future the sustainability of their action.

The tuna fishermen I met face nature not to dominate it, but to measure themselves against it, extracting the minimum they need and thus ensuring the longevity of the fish stock for future generations. Ultimately, it is one of the few examples of an industry that we would call sustainable today; it seeks profit but gives up an immediate part of it to ensure its reproducibility in the future.

This practice, by the way, is not taught in schools or universities, but is the result of a practical transmission that has been going on uninterruptedly from generation to generation for millennia.

Back to the theme of points of view, looking at the photos taken with the drone brings to mind projects drawn in negative, but also drawings and monumental works of the ancient past, whose practices are still partly mysterious: how much has the awareness of being faced with the documentation of a fishing technique that has its roots in a past in many ways still obscure influenced your work?

Yes, generally in my visual research work I often play with the second degree, that is, with the possibility of exploiting the ambiguous potential of the nature of images. In doing so, I have found it more interesting to use images and sequences not so much to offer easy explanations of reality, but to create visual paradoxes, short circuits of meaning, curiosity... ultimately, to stimulate questions. I believe that today it is important to reactivate, as far as possible, critical thinking as opposed to a standardized and homogenized vision of reality that anesthetizes minds and consciences.

So, the nets from above seen by the seagulls can also be — or seem, for the humans who observe these images, to be — unseen constellations in the night in which we are lost, and to which we appeal to seek new paths of meaning.

The nets of the trap, then, are physical constructions composed of rooms arranged in a straight line and which underwater resemble a building. These rooms begin with a labyrinth where the tuna is invited to enter, and end in a larger place called "room of death." This enclosed space, in its entirety, is not made to kill fish but to put them under the control of men in order to select, and then kill and profit from them, only the most interesting specimens, releasing at the end of the process the younger ones. From a symbolic point of view, it is an architecture that separates the natural and wild space, outside the trap, from the controlled one in which man has a chance of success, inside the trap. An architecture that, seen from above, makes you perceive how much the immensity of the natural space overcomes the reduced dimensions of the trap itself.

On the one hand, then, the tradition of sustainable fishing, based on thousands of years of experience and handed down as a method of subsistence and protection of the ecosystem; on the other hand, the technology of its industrialized version, practiced mainly by foreign countries in the international waters of the Mediterranean and a real threat to our seas. Or else, the sacredness of the direct relationship between man and nature against the logic of pure commercial exploitation of one by the other: what can you tell us about the cultural and media misunderstanding that criminalizes the traps?

Yes, you are right, it seems like a paradox, but it is not. My intention is to point out that this type of fishing, apparently brutal in its end (the killing of large fish), is not only to be preferred to the technologically advanced type, which is certainly more profitable but highly destructive and predatory, but it becomes exemplary precisely in its rarity as an important and perhaps last chance for man to take an unprecedented step towards acting in balance with nature, in which nature finally has a chance to survive our destructive fury. On the other hand, these days it is clear that nature can react to our will of blind power, where the viruses that see their ecosystem threatened are looking for their last territory of survival in the dominant humans.

The few traditional and sustainable tuna fisheries still in operation are an example of how a balance can still be recovered; if they disappear, we will lose this knowledge forever and with it the possibility of having an alternative to the brutality of technological domination over nature.

In the traditional fishing of bluefin tuna in the Sardinian “tonnare” you can find a very strong symbolic level, which gives space to a more complex reflection that is in turn at the center of your wider work: would you like to tell us about it?

"Sale Sudore Sangue" is a rib of a larger project that I have been working on for years. I called it “Hybris”, a Greek term that indicates the characteristic of men unable to recognize the limits of their action. The ancient Greeks knew that if they stepped on the territory of the gods, going beyond the limits, they would suffer their wrath, in the form of natural disasters or pestilence and misfortune. In my vision, the gods are being replaced today by nature.

The project is divided into four parts, which correspond to the natural elements. The first one is dedicated to the Aqua element and, although it includes it, it does not end with the work on the tuna nets. In order to realize the book, now blocked by the pandemic but soon to be published by the French publisher Delpire, I have been in different places of the Mediterranean, such as Sicily, Calabria, Sardinia, Greece, but also in Senegal. It is in this project that I experiment in a very marked way the evocative and symbolic potential of photographic images, using both black and white and color, but also more sophisticated forms of processing.

Also as part of this project, and in confirmation of a research in constant evolution, Zizola wanted to add to the language of still images an experimental short film, where the images are in movement. In the 18 minutes of “As If We Were Tunas” the play of parts staged in the book becomes even more vivid, and the paradoxical identification with the tuna even more than with the fishermen leaves one dazed, with a feeling of raw unease but also of vitality and in essence of admiration and respect for a practice of which perhaps not enough is known. Presented out of competition in the Authors section at the 2018 Venice Film Biennale, received the SIAE award for creative talent ‘for a visual language of great intensity and for the skill with which it uses sound and image’.