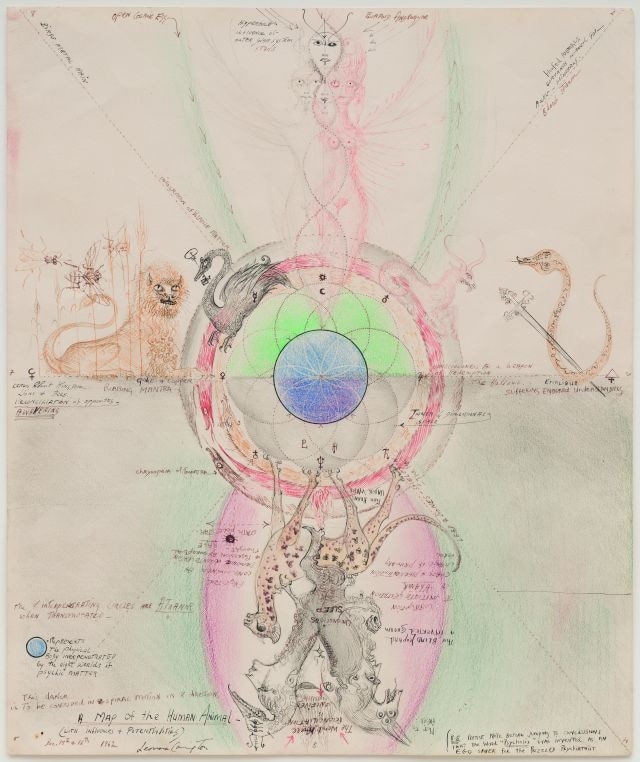

Always on the run. From her family, from bourgeois conventions, from values that never felt like hers. And later, from cities, lovers, schools and psychiatric hospitals. Carrington fled many times. The first escape came in childhood, when the Irish fairy tales and Celtic myths told by her mother became a portal to a world of mystical salvation. She spent long hours at the zoo, convinced that “each of us has our own inner bestiary.” Hers was just beginning to take shape.

Fourteen years after her death — and three years after Cecilia Alemani paid tribute to her at the 2022 Venice Biennale — Palazzo Reale in Milan is hosting the first Italian retrospective devoted to Carrington, the artist who made the fantastic, alchemy and the unconscious her true visual language.

Between disobedience and Surrealism

Carrington was not so much a rebel as she was disobedient. She didn’t destroy order; she chose carefully which systems to overturn. Born during the First World War, she clashed early with her wealthy British family, owners of textile industries and active in trade. They sent her to a Catholic boarding school in an attempt to rein her in. Instead, she got herself expelled and, not yet eighteen (in 1936), moved to Florence. There, the Italian Renaissance met Celtic folklore, harmony met mysticism — and a first portrait of the artist emerged: a vessel capable of holding even the most incompatible worlds.

I didn't have time to be a muse-I was too busy rebelling against my family and finding my own way as an artist.

Leonora Carrington

Love or Surrealism? In 1937, in London, Carrington found both in the figure of Max Ernst, the celebrated German Surrealist. What opened before her was not only the irrational passion of youth but also a hunger for the new. She crossed paths with Lee Miller, the American photographer and model, and Leonor Fini, the Italian-Argentine painter known for her defiantly feminine portraits — both already fixtures in the Surrealist circle. But Carrington soon realized that even within the movement founded by André Breton, the space for a truly free woman was limited.

“I had no time to be a muse,” she later recalled. “I was too busy rebelling against my family and finding my own path as an artist.”

Her affair with Ernst also burned fast. In 1939 he was deported to an internment camp in France, leaving her alone. Emotional collapse overwhelmed her, leading to confinement in the asylum of Santander, Spain, where doctors branded her “incurable.” Out of this abyss came Down Below (1944), her harrowing autobiographical account of breakdown and rebirth, described by Breton as “one of those journeys from which one has little chance of returning.”

Redemption in New York, a new life in Mexico

If her time in New York seemed to restore some stability, the call that truly shaped her destiny came from Mexico. She moved there at just twenty-six — and never left. Mexico offered her new inspiration and new forms: paintings, sculptures, tapestries, papier-mâché installations and lithographs. She grew close to Frida Kahlo and to Spanish Surrealist Remedios Varo. Together they took part in the Mexican feminist movement and in the landmark exhibition La mujer como creadora y tema del arte — a turning point both for Mexican art and for that strand of Surrealism seeking, far from Europe, a new understanding of women’s bodies and lives.

Under the Mexican sun, Carrington also became a mother, an experience that inspired The Giantess (1947), her most iconic work: a majestic lunar-faced figure holds a speckled egg, while wild geese wheel above a golden field of wheat. At the dawn of the new millennium, Mexico honored her with the title of mujer distinguida, acknowledging the cultural and political impact of the exiled intellectuals who had made the country their home during and after the war.

People often say one lifetime is not enough. For Leonora Carrington, her ninety-four years were enough to be everything — artist, writer, exile, migrant, mother, activist, feminist.

An inner ecosystem, or better yet, a “bestiary” in which all her identities could coexist. All except, of course, that of the muse.

- Exhibition:

- “Leonora Carrington”

- Curated by:

- Tere Arcq and Carlos Martín

- Where:

- Palazzo Reale, Milan, Italy

- Dates:

- 20 Sept 2025 - 11 Jan 2026

Opening image: Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Paisaje, torre, centauro 1943. Collection Peréz Simón © Estate of Leonora Carrington, by SIAE 2025. Courtesy Palazzo Reale Milano