The elegant silhouette of a young seated woman in a kimono, with an industrial port in the background, is the powerful image by Nobuyoshi Araki chosen to advertise the summer exhibition at the Astrup Fearnley Museum in Olso, dedicated this year to the collections of the Selvaag Real Estate Group. It is not simply a focus on the splendid collection, but also the story of the successful architecture by Renzo Piano located on the city’s sea front. In an ex-port area, it is a celebration of the still-new museum and the project, closely tied to a private group which has re-qualified the entire area of Tijuvholmen. This is a success for the Astrup Fearnley whose park, open to the public, permanently hosts some important sculptures from the collection. Selvaag carries forward its vocation which began in the 1950s and 60s when, alongside the construction of affordable housing, the real estate group also commissioned and placed works by Norwegian artists, creating an opportunity for the arts.

View gallery

View gallery

In more recent years, with the collection becoming international, sculptures by Anish Kapoor, Louise Bourgeois, Franz West and Ellsworth Kelly have become an integral part of the walk along the fjord. The title “I still believe in miracles”, taken directly from a famous work by Douglas Gordon, makes reference to a miracle which has probably already happened. To the attentive eye, the young woman in the photograph appears focused on eating a piece of watermelon which has been roughly opened. The red of the pulp matches that of her undergarment, and makes reference to the brick red which for almost a century was the dominant colour of the port front in the city, in chromatic continuity with the colour of its municipal monument, the neighbouring Rådhus. Edvard Munch, at the age of seventy, dreamed of decorated its hall, inspired by the work of those who built it. The design was not even officially presented. This is an episode which now seems like a prophecy for the recent increase in the concentration of art in the down-town area of the new Oslo. It is probable that the economic boom linked to petroleum resources directly inspired neither the boring post-modernism of the Bjørvika bar code project or the white marble which covers the Snøhetta Opera House, but with Renzo Piano’s “sail”, these venues have been given a breath of fresh air for Norwegian art.

View gallery

View gallery

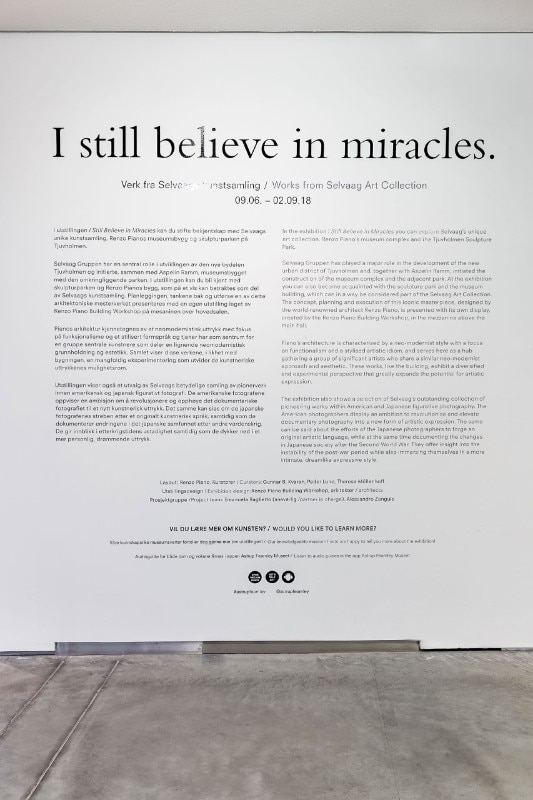

The exhibition is therefore not completely innocuous. The director, Gunnar B. Kvaran, the gallery owner and art advisor to the Selvaag brothers, Peder Lund, and the curator Therese Möllenhoff aim not only to reflect on a private collection, but directly on the culture of a city. This is a way to understand what is going on in the area. Along the Oslo seafront, we will soon see the arrival of other cultural institutions which are abandoning their traditional locations, the brand new Nasjonalmuseet and the future Munch Museum, currently under construction but soon to be completed. The presentation of the Selvaag Art collection is a precise examination of the relationship between private collecting and its public role. An open discussion with the Scandinavian art scene which hints at much wider-ranging cultural consequences. As was the case with architecture critics of the past, the exhibition identifies several assonances between the works exhibited and the building designed by Renzo Piano. It reflects on neo-modernist aesthetics which link buildings to content. In the work of the Italian architect, there are no signs of the institutional fatigue or surrender which are beginning to emerge in the solutions proposed by the contemporary architectural star system. In one of the museum’s most beautiful halls, with its intimate and breath-taking sea view, The Lucky Stone by James Lee Byars from 1980, Lenticular 11 by Mike Kelley and Asshole, a 2017 drawing by Paul McCarthy which is a caustic caricature of Donald Trump, are aligned in a monastic manner.

The challenging work of the curator is a success in the perfect setting of the building by Renzo Piano, lending an algid and timeless beauty to a recent magnificent glass sculpture, Untitled 2016 by Roni Horn. It is very clear that in order for contemporary art to involve its audience in its fruition, it needs to re-define the rules of consumption which concern it. Seeing it exhibited in an architectural masterpiece consolidates its future economic value. In this case, the aesthetic and anthropological set-up becomes self-evident.

View gallery

View gallery

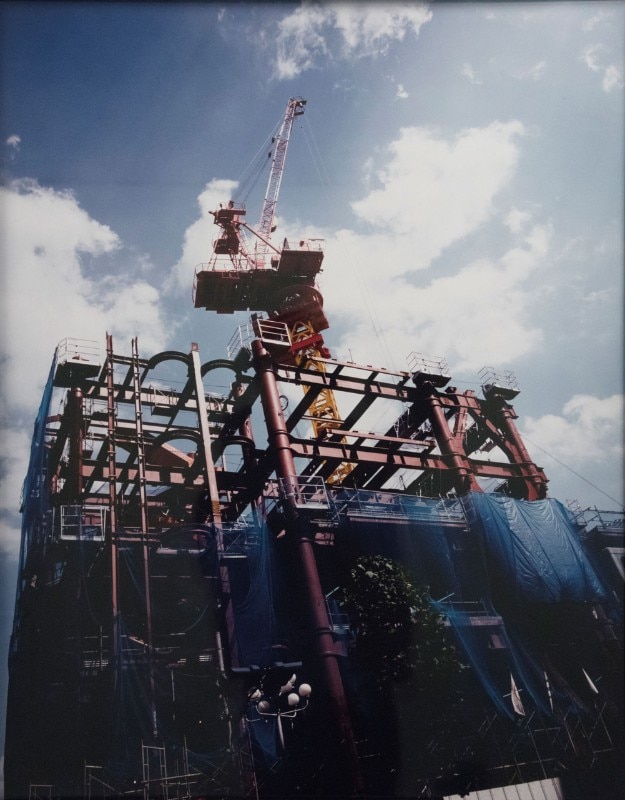

Piano is the architect responsible for the Pompidou centre, he radically modified the rituals of the museum approach. The story of his work in Oslo is explained in extreme detail in the heart of the exhibition. One understands that this adventure is most definitely part of the DNA of the collection. Renzo Piano himself, together with Emanuela Baglietto (partner in charge) and Alessandro Zanguio, designed the layout, re-designing the circulation and division of the exhibition spaces. Each work is inserted in a precise layout, constructed from panels suspended in the space, which prolong the architectural experience. The original drawings by Piano in his characteristic green, his notes and photographs of the work site form part of the exhibition space. The beautiful maquettes of the museum communicate with a monumental work by Paul McCarthy. The minimalist Ellsworth Kelly seems to mimic its forms, and a small Kapoor in gold reflects its preciousness. Everything is decidedly in harmony with the splendid form of the building itself. The soaring lines of the iconic silhouette of its roof literally graze the garden on the fjord, and here it merges with its sculptures. It is the most evident gift that the Selvaag Art Collection has made to a city in full renovation. The successful equation in the relationship between public and private is becoming a positive model to be replicated.

- Exhibition title:

- I still believe in miracles

- Opening dates:

- 9 June – 2 September 2018

- Venue:

- Astrup Fearnley Museet

- Address:

- Strandpromenaden 2, Oslo

- Curators:

- Gunnar B. Kvaran, Peder Lund, Therese Möllenhoff

- Exhibition design:

- Renzo Piano Building Workshop

- Design team:

- Emanuela Baglietto (partner in charge), Alessandro Zanguio