"As a matter of fact, if modern physics is to be believed, sight, prudently employed, gives us a more delicate knowledge concerning objects than touch can ever do. Touch, as compared with sight, is gross and massive. We can photograph the path of an individual electron. We perceive colours, which indicate the changes happening in atoms. We can see faint stars even though the energy of the light that reaches us from them is inconceivably minute. Sight may deceive the unwary more than touch, but for accurate scientific knowledge it is incomparably superior to any of the other senses."

Of course, when talking of art exhibitions in public galleries, the irony of all this — never mind that Russell is talking about physics, not art; light is light, after all, whether art or photons — discussion of the relative merits of sight versus touch is that in art galleries you often aren't allowed to touch anything at all, and must rely entirely on sight for deduction and interpretation.

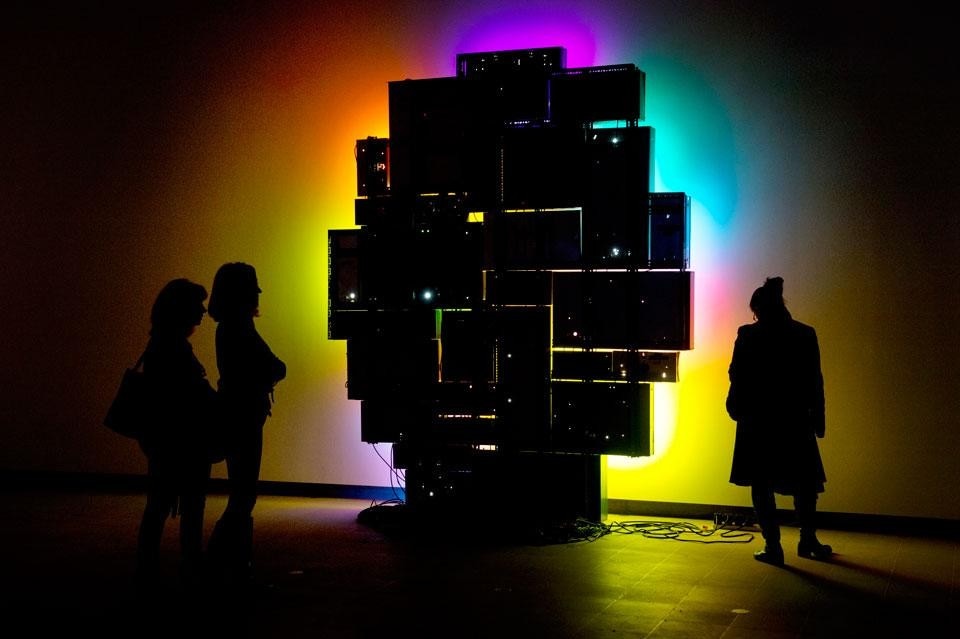

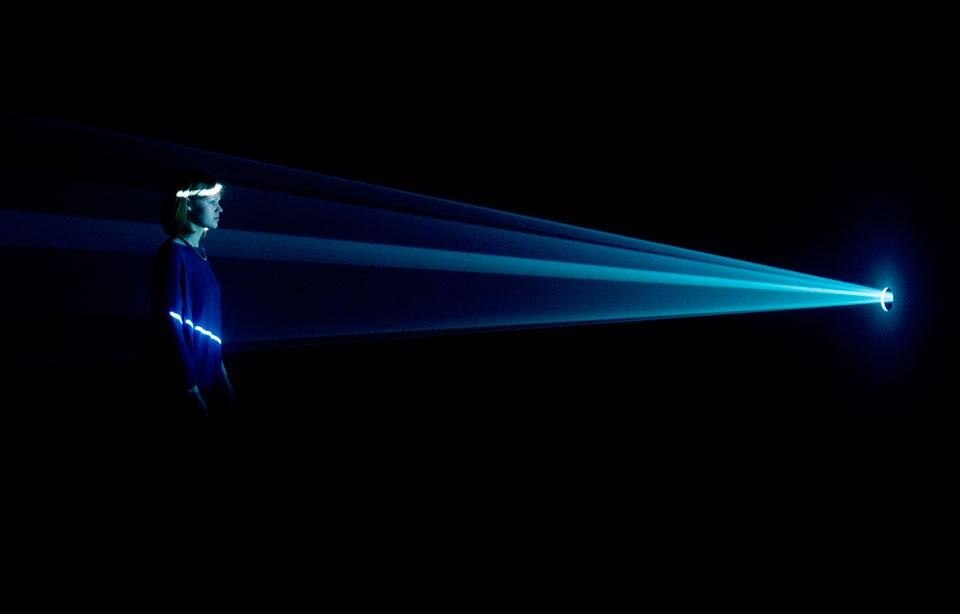

But this is all much of a muchness as regards Light Show, an exhibition featuring 22 artists, the majority of which featured here were born between 1923-1968, with only three born in the 70s and one in the 80s. Light Show isn't necessarily intended as a celebration of the old grandees of light art, though they're all present and correct with works by Dan Flavin, James Turrell, Anthony McCall and Carlos Cruz-Diez. The presence of younger artists like Katie Paterson and Conrad Shawcross, to the exclusion of many other contemporary artists who trade in light, can in fact be explained by the exhibition guide, which mentions that the works have been selected for their exploration of how artificial light can be used to create a sense of sculptural space that plays with human perceptual responses.

When it comes to light and art and perception, half of the fun is in figuring out the trick for yourself. Or in not figuring it out and enjoying it anyway

Light Show

Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre

Belvedere Road, London