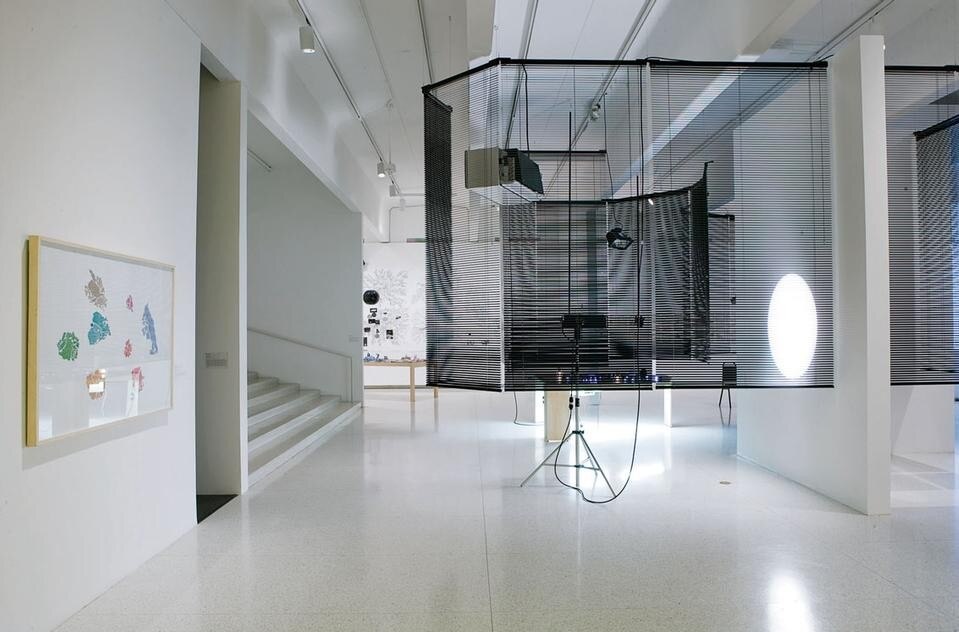

This process of observation and alteration is also present in the manner in which Yang constructs space. Concentrating on the most precarious of details, she has made the condition of ephemerality a central aesthetic principle of her practice. In the installation Series of Vulnerable Arrangements – Blind Room, 2006-2007 (in the exhibition “Brave New Worlds” at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis), which serves as a viewing space for the video trilogy, she conceived an indoor pavilion that conceals as much as it reveals. Made from dozens of black Venetian blinds that have been rolled down to their full length, these horizontal lines divide the space into four enclosures. Slightly titled at 60 degrees, the shades let less than half the light filter through. The blinds’ overall layout follows a precise diagram that appears to take its shape from the creases left on a piece of paper previously used for origami, as mountain folds and valley folds repeat throughout the space. Fronts and backs, positives and negatives are played against each other to form a moiré of lights and shadows. Thresholds between each blind allow light to filter through vertically, while the open space below makes visible its interior: a quartet of chairs and stools, a table, electrical cables, and two freestanding lamps.

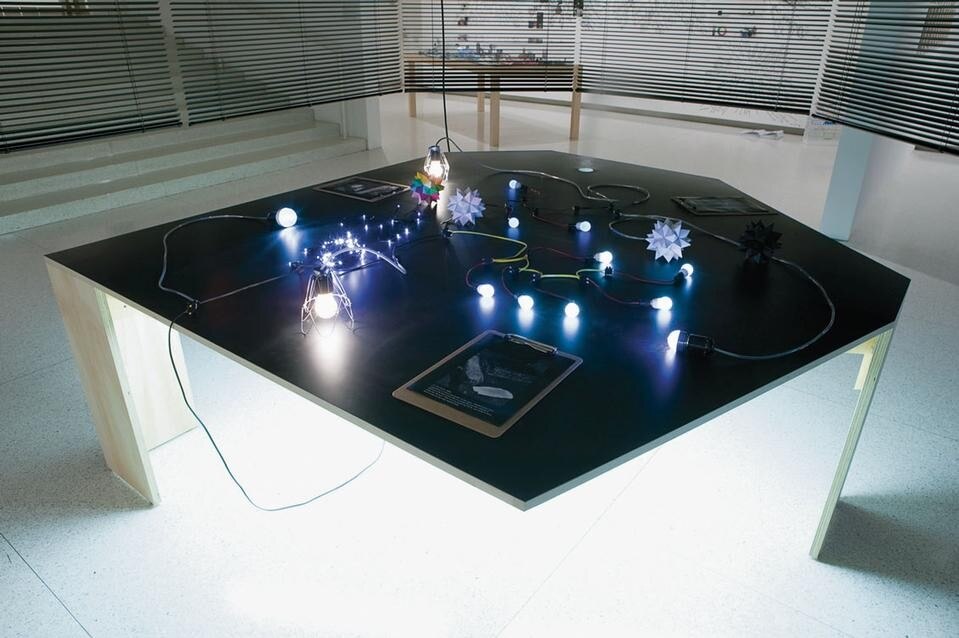

The doorway to Yang’s Blind Room is marked by visual and sensorial effects: the cool breeze from an air conditioner above the entrance, and a warm blaze emanating from an infrared heating lamp on the side. In front of us, a large white disc projected on the wall attracts our attention: an enormous spotlight has been set up, perhaps for those who desire to be watched or listened to, or maybe neither. In the adjacent room is a table with objects laid on it, surrounded by a pathway that allows us to take a closer look. An element of solitude permeates this area, as we understand before entering that the path is only wide enough for one person at the time. As a result, we must maintain a certain distance from both the person in front as well as the person behind. A bitter smell similar to burning tyres greets us as we enter the space, reminding us what revolting smells like. On the table, Yang has arranged a series of delicate light strands, a number of colourful pieces of origami in the shape of stars, and placed photocopies of photographs on clipboards for us to observe. A humidifier below the table creates a cloud of steam that rises steadily through a hole, turning the table into a miniature stage set for a tale that we have to invent. As we leave the space we are offered one last scent, but this time we recognise the undeniably familiar smell of clean laundry. The objects in Yang’s custody are never arbitrary or solely material symbols. In her concept of social relations, light, heat, smell and sound are tangible forms coded with image value and charged with the nobility of having more than one function. One of Yang’s recurrent objects, the light bulb, takes on a referential status through its “behaviour” in shadowy spaces, ranging from bold autonomy to shy reclusion. These objects of light vary in scale, colour and voltage, for she is not only seeking illumination but also the gesture of presence to be enacted in a given space. On the table in Blind Room she offers groupings of two, four and six lights in the form of constellations, but together they constitute a single white light that twitches energetically in complete anarchy, blinking for its own sake. Another reappearing object in Yang’s lexicon is the Venetian blind. These blinds split and reconcile space by affirming and denying light. In Yang’s cosmos they function as a surrogate for perception, pointing to the subjectivity of seeing. As the artist has stated, “I’m fascinated by the blind and its function of filtering light and creating a kind of half-transparent wall between two spaces. It is that space between people that I’m very interested in. You are not alone. You can see other people walking through the half-shadow, half-light. You are sharing but not sharing” (in “Artist Haegue Yang at Redcat” by Lynne Heffley, Los Angeles Times, 16 July 2008). In Blind Room, lights and blinds mark moments of transition but also transactions, abstracting social relations between the “I” and the “You” into discreet coexistences, simultaneously suggesting proximities and distances, and playfully teasing us into being and not being.

The third enclosure of Blind Room presents Yang’s video trilogy showing on separate screens. Accompanying the moving images are individual voice-overs narrating anecdotes of odd encounters, meditations on the human “pursuit of place”, as well as reflections on the artist’s voluntary exile. Yang’s visual and textual contemplations of displacement examine the conflicting relationship between foreign land and homeland with a sense of protestation. “Even if most of my work is led by a voice of silence, it is engaging the ‘act of speech’ with a potential addressee,” says Yang. “It is a dialogue between ‘singularities’, whose location is rather vague whereas his or her identity of ‘homeless’ is definite, remembering Bataille’s concept of the ‘community of absence’. Even if the footage derives from various places, the work does not submit itself to any travel experiences. The voice-over is contemplating about being lost, constantly losing oneself, negating distinctive territories, lacking courage, while various minor informal urban scenarios as well as staged elements are unfolding” (from the exhibition catalogue of the 27a Bienal de São Paulo, 2006, curated by Lisette Lagnado and Adriano Pedrosa). But what does it mean to be “constantly losing oneself” when we are talking about seeing? In what way might losing oneself imply losing sight, as an affirmation of a necessary blindness that returns us to seeing and perhaps finding? Tucked in behind the wall of the third room, a row of blinds extends beyond to form an exterior room of its own. Inside we find a round mirror hanging on the wall, hidden. Its diameter matches that of the spotlight projected on the other side of the wall, at the entrance of the room. One must exit Blind Room to see this last calculated arrangement, implying that in order to see one must find. Here Yang’s poetic irony arouses our curiosity one last time. Piercing through the blinds, one finds homeland, one sees oneself. The image of seeing, if one may call it that, is an image of finding oneself. “Fear can cause blindness, said the girl with the dark glasses,” writes José Saramago (from Blindness, The Harvill Press, London 1997). “Never a truer word, that could not be truer, we were already blind the moment we turned blind, fear struck us blind, fear will keep us blind, ‘Who is speaking?’ asked the doctor, ‘A blind man,’ replied a voice, ‘just a blind man, for that is all we have here.’”