Can an astonishing museum become a chance for the city’s redemption? Text by Lea Vergine. Photography by Peppe Avallone. Edited by Loredana Mascheroni

Google Earth: 40 51' 17.47" N, 14 15' 31.29" E

http://www.museomadre.it

Fight the Anti-city

Lea Vergine

This is the city where you can visit the Archaeological Museum’s Sala della Meridiana during a national preview and gaze at treasures from the Chinese Tang dynasty predating 1000 AD. This is the same museum space that has in recent years hosted major solo shows by artists from Richard Serra to Nino Longobardi. In this city you can go up to the Capodimonte Museum and see Mimmo Paladino’s latest effort, Don Quixote; a city where it is still an extraordinary experience to walk through the ambulatory of Castel del’Ovo to take another look at Carmine Di Ruggiero’s informal period. In another part of this city you can go up to Castel Sant’Elmo for an exhibition on Domenico Morelli, or visit the 18th-century Palazzo Roccella in Via dei Mille, today called PAN (Palazzo delle Arti Napoli), and find contemporary art illustrated, albeit debatably, through the activity of local galleries (nearly two hundred works). Or, on your way to Piazza Plebiscito, where the annual installation is located, you can get off at the numerous metro stations where local, European and American artists have contributed to an enormous open-air museum.

The fact that this city exists makes it unique in Europe. If we add the spaces of the neoclassical Villa Pignatelli and the Palazzina in Villa, the halls of Palazzo Reale and the Aragonese Maschio Angioino, we count ten venues for contemporary art exhibitions. Another space can be found at Palazzo Donna Regina, called MADRE. So what’s Naples doing? Is it cyclically reborn? “History is made slowly here. Above all, it is an exotic history, an invention flavoured with Homer, with cyclical poems and innumerable fragments of legend, fables, tall stories, tavern brawls and flashing knives, adultery and nostalgia… Someone died in Naples before Naples even existed. Then, between the deep silences and deserted spaces, a murmuring was heard, a constant babble of sirens. Parthenope was a siren and a city; she was Greek and she died for love. She was a Goddess, a place, a street, a tavern; she was miraculous and should be revered. Parthenope is here and everywhere, stealthily springing from the sea, here where she is named after a nymph and the nymph will be sacred through the centuries. The city will not die, the nymph-city will not die.” So says Giorgio Manganelli (in his writings collected under the title Salons, published by Adelphi, Milan 2000).

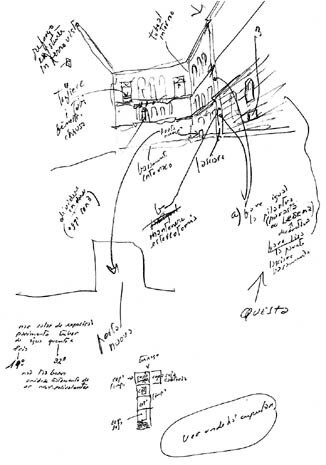

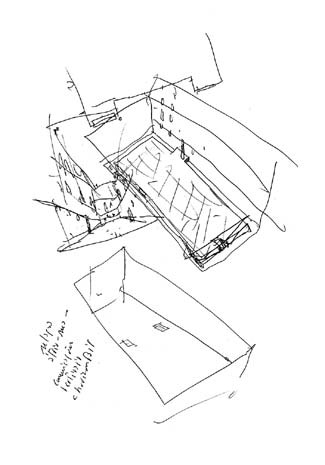

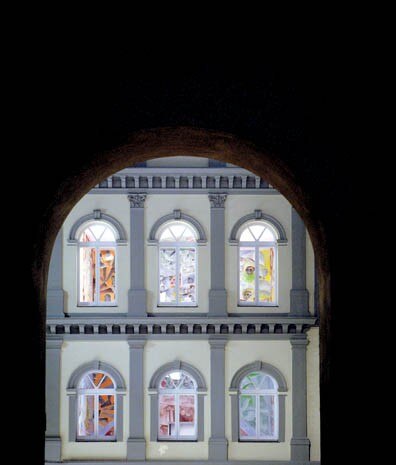

The Madre has been open since last June in Via Settembrini, in the San Lorenzo district. Not far from the Cathedral and the Monastery of Santa Maria di Donna Regina, it was bought by the Regional Council with the aid of European funds in March 2004, together with the project by Álvaro Siza. The cost of obtaining 8,000 square metres of museum space came to forty-two million euros. There is an inner courtyard of about 500 square metres for large-scale installations, and another slightly smaller one for usual museum services. There will be an enormous functional terrace, with the internal exhibition spaces spread over four levels. A lot of nonsense has been said recently about the origins of the exhibited works and the omission of Neapolitan artists. In reality there are six locals – from Carlo Alfano to Francesco Clemente and Gianni Pisani – while on the first floor Kapoor, Kounellis, Richard Long, Rebecca Horn and all those invited over the past decade to write the artistic history of Piazza Plebiscito, are represented by works purchased by the museum (and also by some donated pieces).

The Council of the Campania region has also acquired (at a cost of three and a half million euros) a number of works representing the past fifty years of artistic study, including Lucio Fontana, Richard Hamilton, Yves Klein, Anselm Kiefer, Piero Manzoni, Mario Merz and Giuseppe Penone. More than sixty artists comprise the exhibition on the second floor, with around one hundred works. There are also works on long-term free loan originating from Neapolitan, Italian, German and American collections. Twenty-eight are on loan from the Sonnabend collection for the next thirty-five years, partly because the museum building is able to satisfy the most sophisticated maintenance requirements like no other place in Italy. Since 10 December 2005, the museum has been open every day. But the old Neapolitan adage that “nothing is done but nothing must be done” (as I was told by Raffaello Causa way back in 1960), still, in a way, holds good. With a shade of bitterness to be sure, it serves to explain the chorus of citizens’ complaints and the anger of a handful of gallery owners based in the city. But what can be held against a museum that was made astonishing through the determination of its director Edoardo Cicelyn and, above all, the regional governor, Antonio Bassolino? Cicelyn is accused of tyranny. The gallery owners – so I am told – would like the director to sit them around the decision-making table and include them in all manner of choices (sharing out the cake). The other objection concerns Cicelyn’s curriculum. He is said to be neither a historian nor an art critic and cannot even boast publications. But what is all this? In that case what objections could be levelled at the governing bodies of the Museo di Rivoli or of the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Rome, to mention just a couple?

People also keep harping on about the age-old problem of criminality in the suburbs and widespread petty crime. “In Italy, the suburbs, degradation and the lack of services are an archipelago, not a belt,” writes Stefano Boeri. “They are everywhere: in the vacant buildings of city centres, in the parks and in disused factories. Have you ever been to the Spagnoli or Sanità districts of Naples? Today the suburbs of European cities represent a mobile condition, a label for multiple landscapes. Let us leave the conquest of the centre, the fourth state on the march towards the bourgeois areas, to the nightmares of those who still believe in the myth of an ancient and rich Centre, in contrast to a recent Suburb given up as a bad job. Leave all that to those who think that history perfectly corresponds to geography… It should be explained to those who see insurrection smouldering in Italian suburbs that the threat to civil life does not come from the suburbs or the outer fringes of cities. No, the truth is that a veritable Anti-city is growing in European cities. Thousands of people, youths, couples and the elderly, are cut off from cultural life, from economic and institutional relations… The riots in Paris have much in common with the rage that for months coursed through the veins of the Scampia or Sanità quarters of Naples… The Anti-city is discovering at its own expense that social mobility, like that of housing, is a mirage… Antibodies against the spread of the Anti-city are not part of any generic ‘anti-suburb’ therapy: they are political. The laws governing welfare, family incentives and the redistribution of income, are political. It is a political challenge facing the governments of European cities – from Paris to Naples – that seem to have lost their bearings.”

But why doesn’t a population with a lofty tradition, but that has also suffered more than a hundred years of international silence, celebrate a situation of this kind instead of continuing to complain of not being sufficiently assisted?