Architecture becomes the spokesperson for those who have no real weight in decision-making processes, despite being deeply impacted by the project—not for one but for several generations.” This is how the Paris-based firm Architecturestudio describes one of its most recent completed projects: the renovation and expansion of the ESSEC university campus (École Supérieure des Sciences Économiques et Commerciales). Over more than fifty years of practice, the studio has consistently framed architecture as a long-term, strategic act, asserting its place within governance processes often confined to clients and developers.

A stake that is both a concrete challenge and a desired attitude for architecture brings us back to ESSEC, one of France’s most prestigious higher education institutions in the field of economics and business. At the end of the 1970s, the business school was among the first to leave behind the cramped classrooms of inner-city Paris. The new campus in Cergy-Pontoise, located on the edge of this suburban city, took the form of a horizontal complex inspired by the model of American universities. At the time, the public transport network, still only planned on paper, had not yet arrived: the car remained the primary means of access to the campus, as evidenced by the presence of a large parking lot. The extent and orthogonality of the layout, the dominance of exposed concrete, and a certain impermeability to the surrounding urban fabric, reinforced over time by security concerns, turned the school into a self-centred, markedly mineral universe.

Architecture becomes the spokesperson for those who have no weight in decisions, even though they are strongly impacted by the project, and not for one but for several generations.

Architecturestudio

Rethinking ESSEC today therefore represents, for Architecturestudio, an opportunity to put into practice this systemic, long-term-oriented approach. Beyond any form of compartmentalisation, architecture itself takes on a pedagogical role, making visible—and where possible guiding—users towards responsible behaviours. Sustainability and new learning models in the age of technological revolution remain crucial questions, but they are not exhaustive. The project also integrates other variables: governance and inclusion, of course, but also the orientation of production chains and the economic foresight of real estate investments, particularly in relation to their chronotopy.

“When working on existing buildings, architecture must lead the diagnostic process, bringing together all available data before making decisions, and operating with respect for what already exists in order to enhance it.” Architecture thus assumes a pedagogical role, showing and, where possible, steering users towards responsible behaviour. Building on this reflection, the architects redefined the forms and functions of the spaces around two main objectives: integrating spaces to make the transversality of knowledge tangible, and reintegrating ESSEC into the urban fabric of Cergy-Pontoise, softening the elitist and isolated vision of an ivory tower intended exclusively for academia and research.

The Research Green Tower—the emblematic tower of the campus, where research spaces and faculty offices were previously confined—becomes the ultimate symbol of this transformation. In the new project, the building is wrapped in a bioclimatic façade composed of double wooden pillars. In addition to regulating solar gain and generating a virtuous climatic cycle, the gallery incorporates a staircase and terraces, both public and private, available to faculty and students. Circulation spaces are thus transformed into opportunities for collective study and learning.

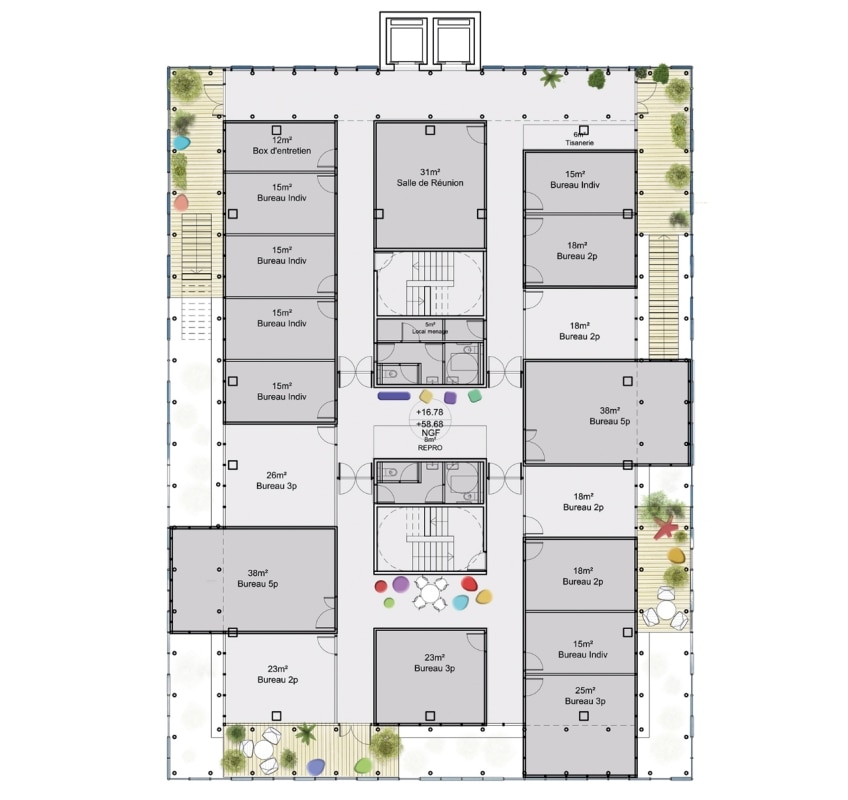

Within the Center for Creative Learning, which brings together the campus’s teaching activities, new interstitial spaces have been introduced alongside the main auditorium and classrooms. Designed to support informal learning, they also accommodate both individual and group study. Beyond the buildings, previously residual areas—including the former parking lot—have been transformed into public green spaces, open to students and to the wider community alike. The gymnasium of the Sports & Recreation Center has also been fully renovated and opened to the residents of Cergy.

As education itself becomes increasingly virtual, ESSEC’s response is not confined to embedding technology within architecture. Rather, flexibility and the capacity of spaces to support different modes of use emerge as the factors that shape the identity of the campus and sustain the desire to cross the university’s physical threshold, beyond the allure of form alone.

This vision has been applied by Architecturestudio across its projects, from the rehabilitation of the Maison de la Radio to the redevelopment of the Jussieu campus in Paris, and theorised in the book Tracé Bleu, a manifesto of their holistic method in a world challenged by climate change. The approach confronts architecture with its own uncertainties—"opening up imaginaries about our powerlessness, or about the need to build reassuring yet creative imaginaries for a near future where norms may no longer be the solution," in their own words. Yet the foundation persists: that the value of relationship remains architecture's surest measure of relevance.