“The collection, really, I have no idea how it even started,” says Pio Mellina. A Palermo-based collector, Mellina is the founder of the Stanze al Genio Museum of Majolica, which opened in 2008, with the aim of making a private collection of antique Italian majolica tiles—assembled over more than thirty years—accessible to the public. Today the collection comprises more than five thousand examples of Neapolitan and Sicilian production, dating from the early sixteenth to the early twentieth century, and is considered one of the largest collections of Italian tiles open to the public in Europe. The museum occupies part of the piano nobile of Palazzo Torre Pirajno, in the historic Kalsa district.

“I remember going to flea markets often with my mother when I was a child. She was fond of antique textiles. I would go along with her, and then I would always ask for a small gift,” he continues. “I liked the tiles, so she started buying them for me.”

A collection born out of attraction, repetition, habit—and, in some ways, spontaneous accumulation. “I never had the idea of creating a collection,” Mellina says. “It really came about by chance.” Over time, however, that chance solidified. Mellina grew up, gained independence, studied, and continued to search, look, and choose. “Then I carried on on my own. At a certain point, I realized I had lost track of what I had and what I didn’t. Fortunately, I always bought different pieces.”

Majolica floor tiles are not simply surface decoration. They are structural components of architecture, capable of organizing space

Maria Reginella, specialist and scientific advisor of the collection

Four centuries underfoot

Stanze al Genio opened to the public in 2008 as a house museum, with a specific goal: to present a collection of majolica as closely as possible to its original function. “They are not objects designed to stand alone,” explains Pio Mellina. “The tiles are meant to be together.”

For this reason, the majolica tiles are not displayed in showcases or isolated as individual pieces, but instead cover the walls of the rooms entirely, placed side by side. A choice that immediately strikes the visitor and reflects a precise museographic approach. “The design is never in the individual tile,” Mellina continues. “The design emerges when you put them together.”

The design is never in the single tile

Pio Mellina, collector and expert

Majolica tiles were conceived as pavements: architectural surfaces designed to be traversed, walked on, and experienced, in dialogue with domestic space and the overall decorative ensemble of the rooms. “The majolica floor tile is not a simple covering,” emphasizes art historian Maria Reginella, who oversees the scholarly aspects of the collection. “It is a structural component of architecture, capable of organizing space.”

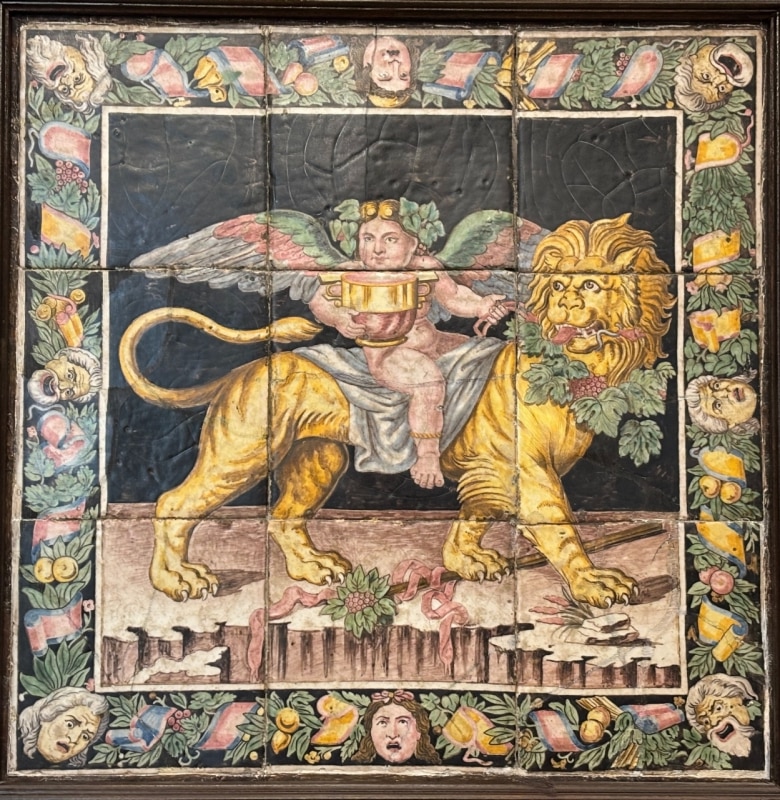

Different types coexist within Stanze al Genio: single tiles, serial modules, and above all figurative panels and fragments of flooring conceived as unitary images. In these cases, separating the elements means losing their meaning. “A panel can be composed of thirty or forty tiles,” Mellina notes. “To divide it is to destroy it.”

These artisans, for centuries, have never repeated themselves

Pio Mellina

The collection spans more than four centuries of production, from the early sixteenth to the early twentieth century, making visible the evolution of techniques and formats. “In the beginning, the tiles were very small,” Mellina explains. “They broke easily under foot traffic, and the kilns were small. Then, over time, the format grew.” From the earliest modules measuring just a few centimeters, production gradually shifted toward larger tiles, culminating in the large nineteenth-century formats.

Geographical differences also emerge clearly. “Neapolitan and Sicilian production developed different visual languages,” Reginella notes. “In Naples, precision of drawing and compositional balance prevail; in Sicily, greater iconographic freedom and strong chromatic intensity.” Stanze al Genio places these variants side by side, showing how floor majolica was never a uniform language, but rather a broad and evolving repertoire, deeply rooted in local contexts.

The challenge of integrity

Many of the challenges Pio Mellina says he has faced over more than thirty years of collecting revolve around a very simple point: explaining to others what he is buying. And why.

“It often happens that antique dealers want to divide the panels,” he says. “A figurative panel can consist of thirty or thirty-six tiles.” Not everyone selling them, however, is aware of their rarity and value. For many, worth lies in multiplying the number of lots rather than preserving the integrity of the work. It is a common practice, one that reveals how frequently these tiles are still seen as stand-alone objects. “But to divide them is to destroy them,” Mellina cuts short. “They completely lose their meaning.”

“Even when I wouldn’t intend to,” he adds, “most of the time I end up buying them all. By necessity.”

Then there is the challenge of travel. “Even when I find them in Rome, getting them home can become a problem.” The tiles, he explains, often cannot travel by plane. “It happened that they wouldn’t let them on board—they considered them improper weapons,” he recalls. “I said: do you realize you can’t put them in the cargo hold? If they had broken, it would have been a mortal sin.”

“These craftsmen, over centuries, never repeated themselves. Form after form, they created a repertoire that never seems to run out. I look at them every day, I keep buying, and I keep wondering how they managed it—and how they kept doing it.”

“Every year we take stock of the situation,” he adds. “Together with Dr. Reginella, we decide what to include and what to move.” Today, ten rooms are open to the public, with more to be added in the future.

“In a sense,” Mellina concludes, “ours is also a potentially endless operation.”