The Austrian town of Baden bei Wien, since 2021 part of the UNESCO network of Great Spa Cities of Europe, was once the summer residence of Austrian emperors and a favored destination for artists and musicians such as Mozart and Beethoven, drawn to its baths and Biedermeier-style palaces.

Today, well connected to the capital Vienna, it remains a sommerfrische where historic and contemporary buildings coexist in balance. In recent decades, new architecture has been integrated into the fabric without imposition, working through both similarity and contrast with the past. One example can be found on an introverted plot overlooking the local streetcar line: a new dwelling designed by Balissat Kaçani and Jann Erhard.

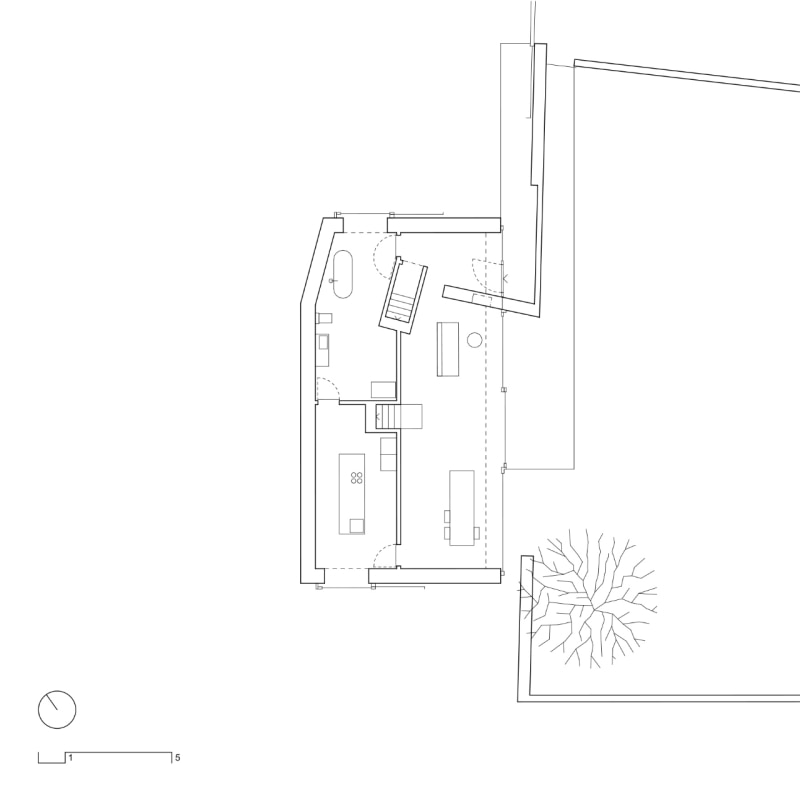

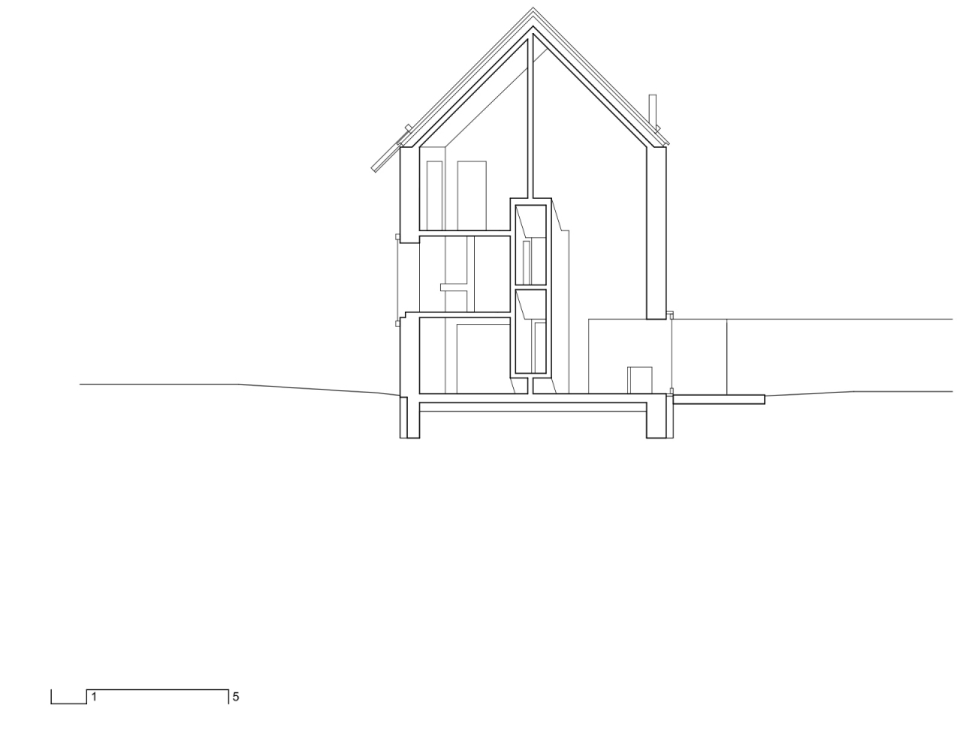

The site preserves the memory of a large private garden that once belonged to a bourgeois mansion, part of which is now occupied by the new house, flanked by tall trees and a pedestrian access path. On one side lies the railroad; on the other, a wall encloses an autonomous, self-contained garden, accessible only through the intimacy of the dwelling. The house thus acts as a threshold, mediating between infrastructure and nature, public space and private space.

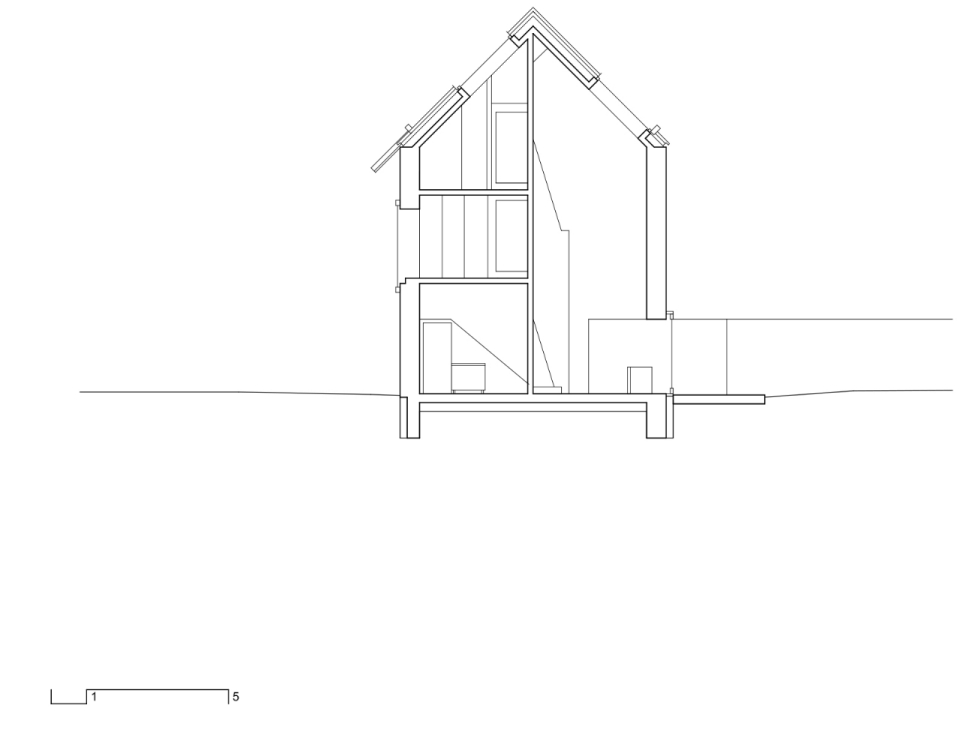

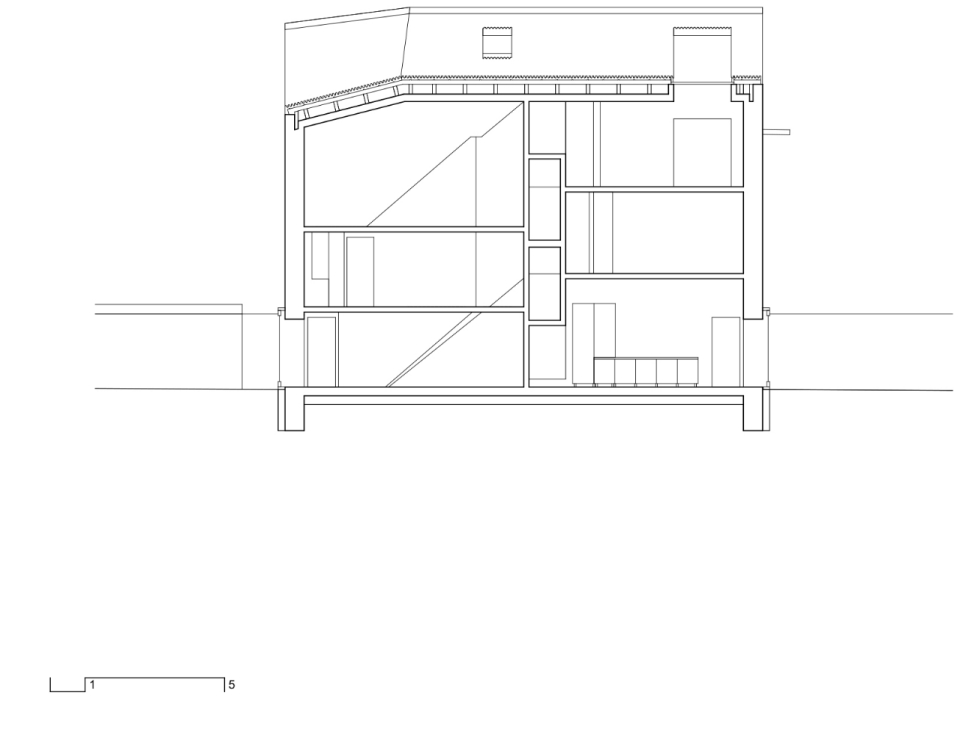

The volume appears as a monolithic mass of reinforced concrete, with an insulation system cast directly into the masonry. The absence of layers and the uniformity of the material give the building an archaic yet innovative character. Walls and floors, made of slender concrete partitions, directly integrate heating and cooling pipes: the house thus becomes a thermoactive body, capable of self-regulation.

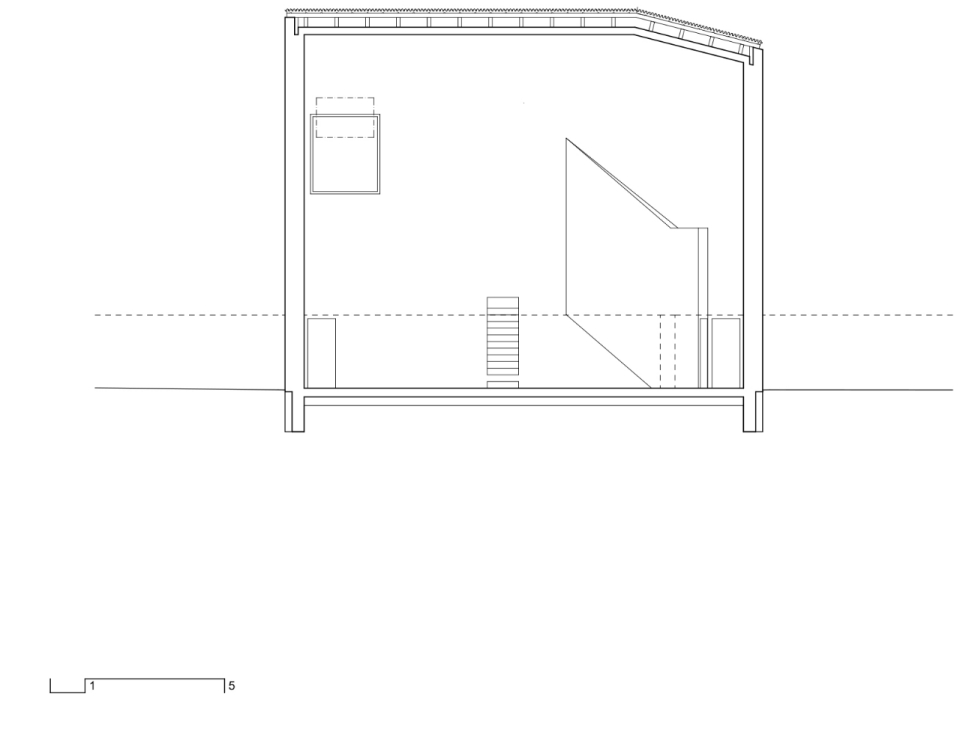

The wall fence from the outside invites toward the entrance of the dwelling and continues into the interior space, which opens longitudinally toward the garden. This space, more than ten meters high, twelve meters long and just over three meters wide, is configured as an empty half of the dwelling, a place suspended between inside and outside, between house and garden.

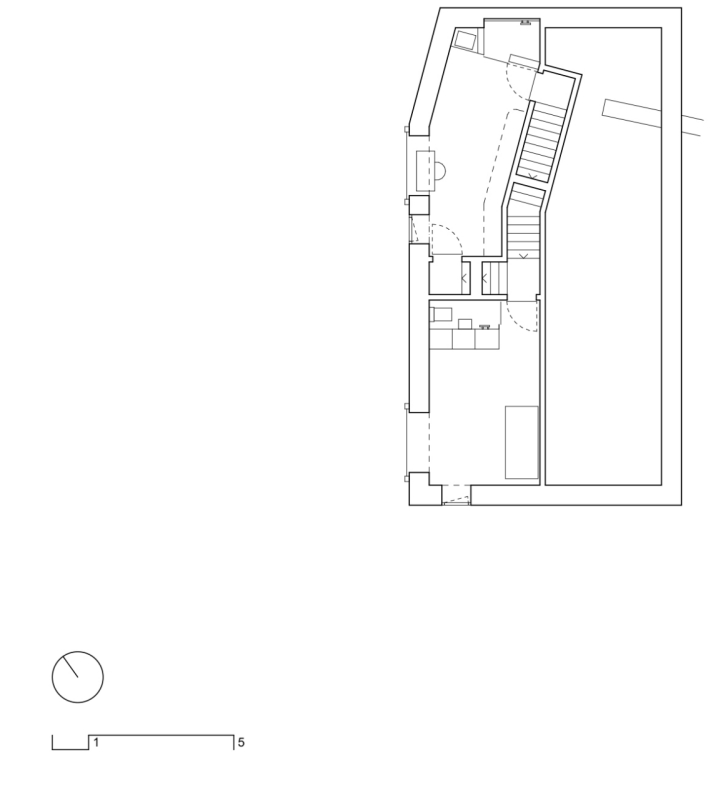

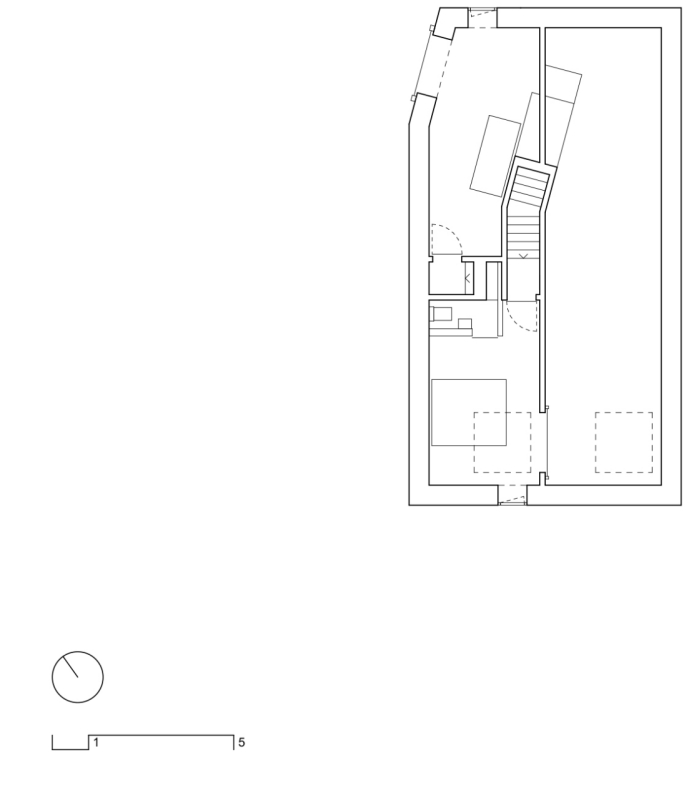

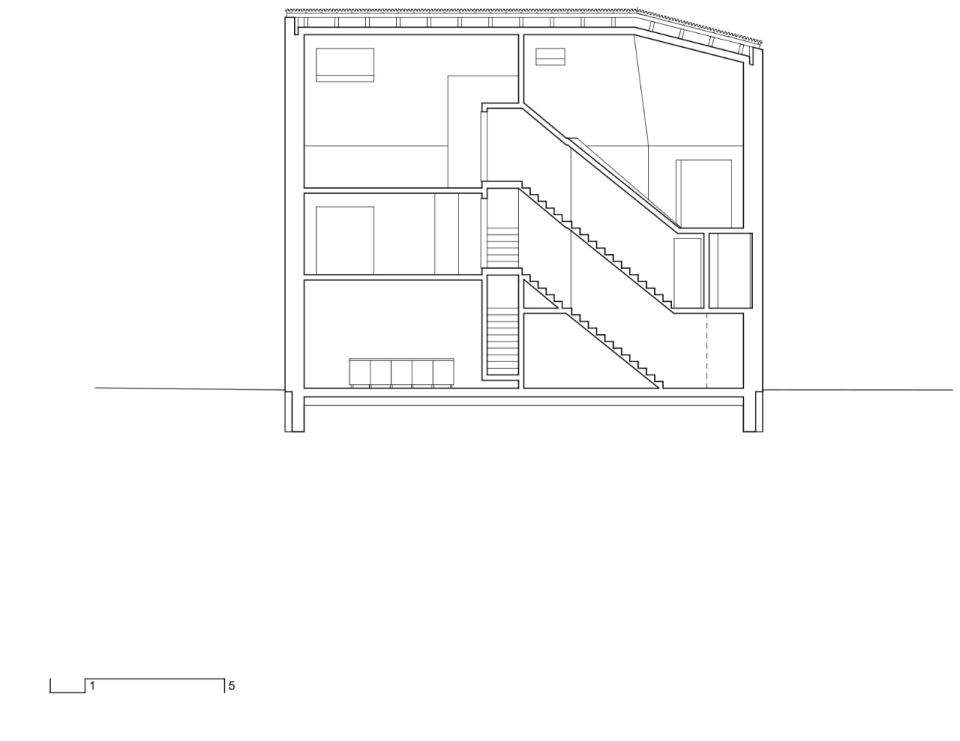

From this crucial space, a system of two overlapping staircases, resembling a double helix, leads to the second half of the dwelling: six rooms spread over three floors, facing the tracks. Identical in surface area, with large windows on the north side and openings for natural ventilation on the opposite side, the rooms gain specificity due to the different heights generated by the difference in height of the stairs.

The two ramps define independent paths, never intersecting yet always adjacent: one leads to two rooms offset by half a floor, the other to a vertical sequence culminating in the highest space of the house. Thus, although physically close, the rooms seem distant, separated by a principle of discontinuity that becomes the dwelling’s defining element.

The result is a complex architecture capable of generating unexpected relationships. A house conceived not only to meet present needs, but also to anticipate future ways of living and to host forms of existence that have not yet taken shape.