The making of the Autostrada del Sole – which translates into “Sun Motorway” – is a glorious moment in the history of Italian highways. A history, it shall be noted, that includes both premieres and shames, records and disasters, framed within two one-of-a-kind events with opposite signs. The very first highway in the world is realized in Italy, in the early 1920s, when engineer Piero Puricelli designs a two-lanes straightaway projected from Milan towards Varese and the Lakes region. Almost an entire century separates its opening from the most sensational Italian highway failure: the collapse of the Morandi Bridge, during a summer storm in August 2018.

Around the middle of the same century, between the 1950s and the 1970s, stands the golden age of the network’s growth. That is a period of huge quantities but also of multidisciplinary reflection on the possible qualities of the infrastructure. It starts during the economic boom, with the multiannual plan established by the Romita Law in 1955. It ends rather abruptly in 1975, when the Law 492 requires the shutdown of new constructions, suddenly made obsolete by the continuation of the oil crisis. In the meantime, the length of the Italian highway network has increased tenfold from 500 kilometers in the prewar period to almost 5,000 kilometers. More importantly, the most ambitious of all Italian highways, the actual backbone of the entire system, has been completed in its main parts: the A1, Autostrada del Sole.

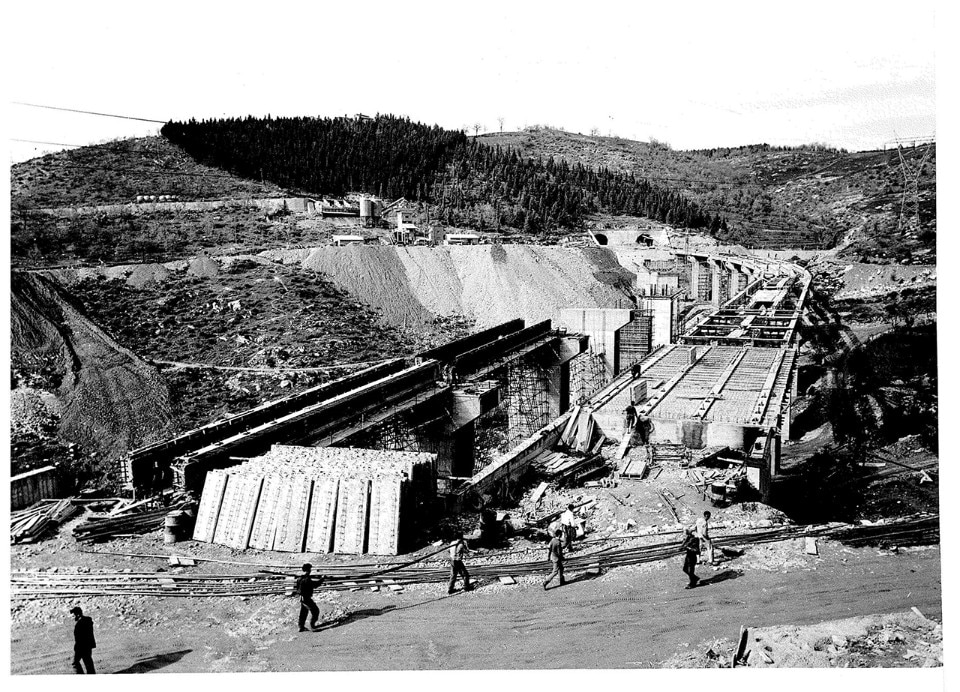

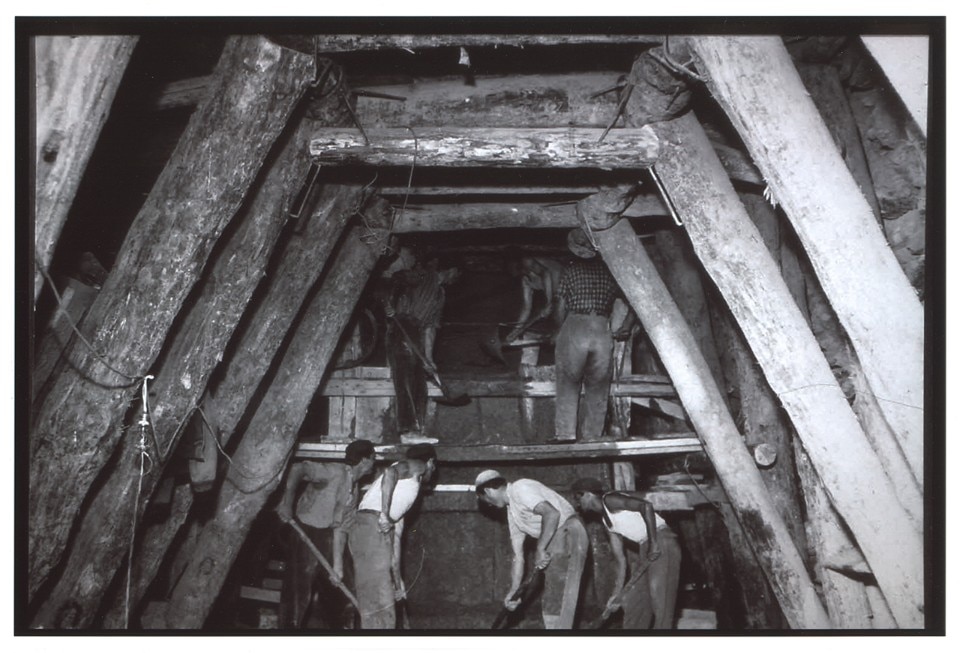

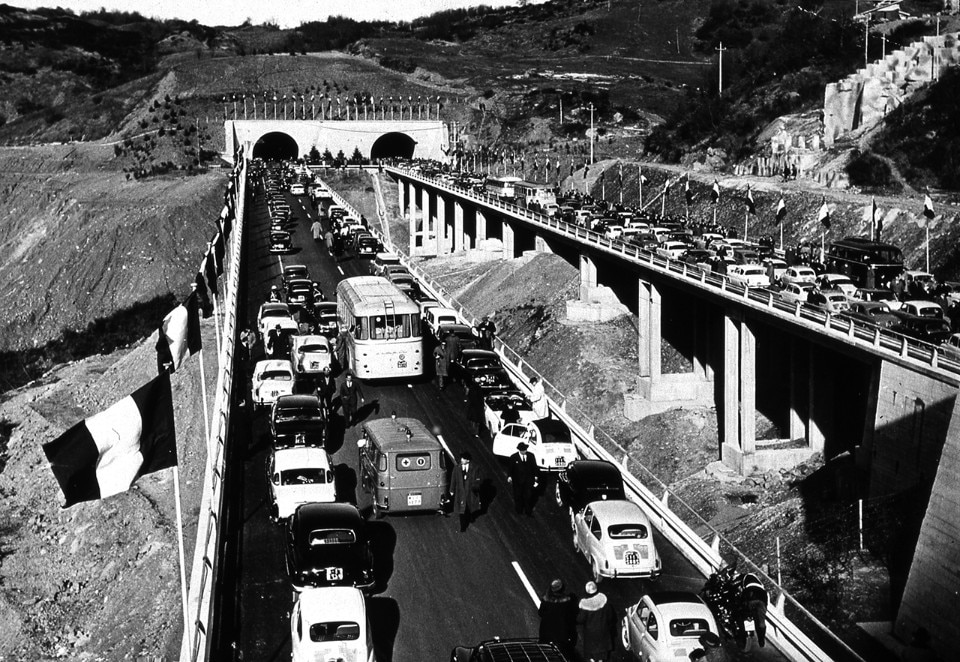

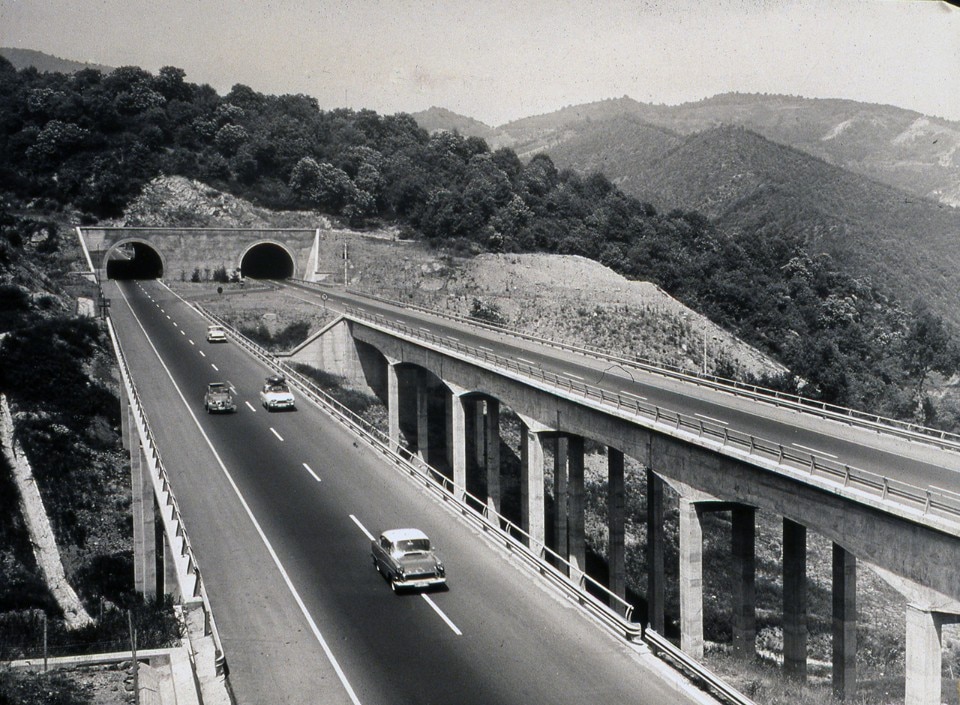

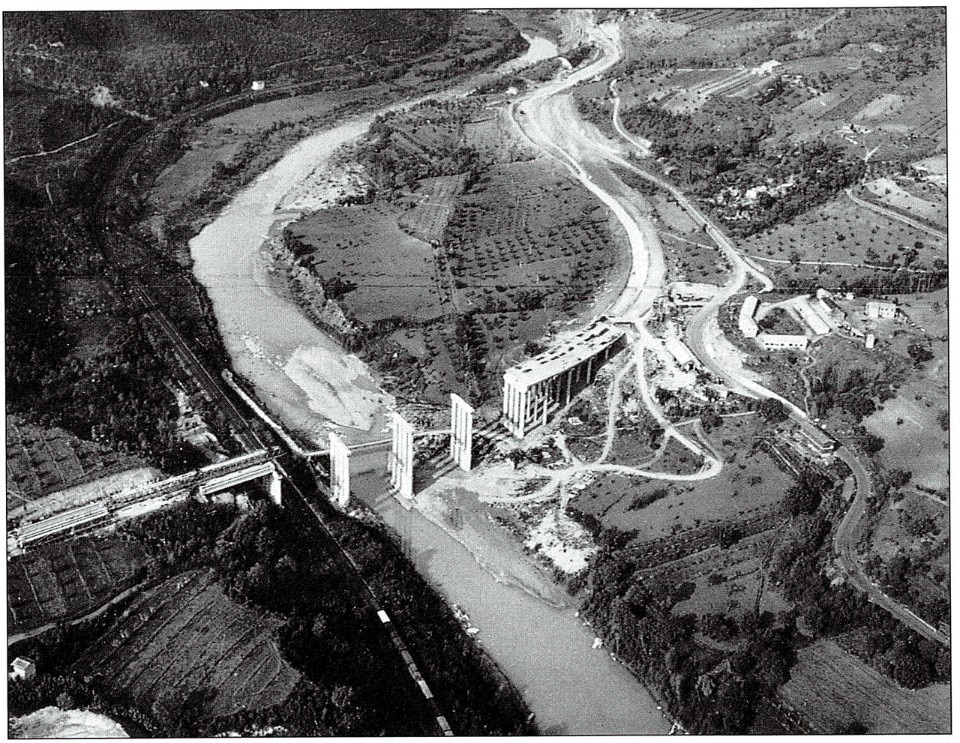

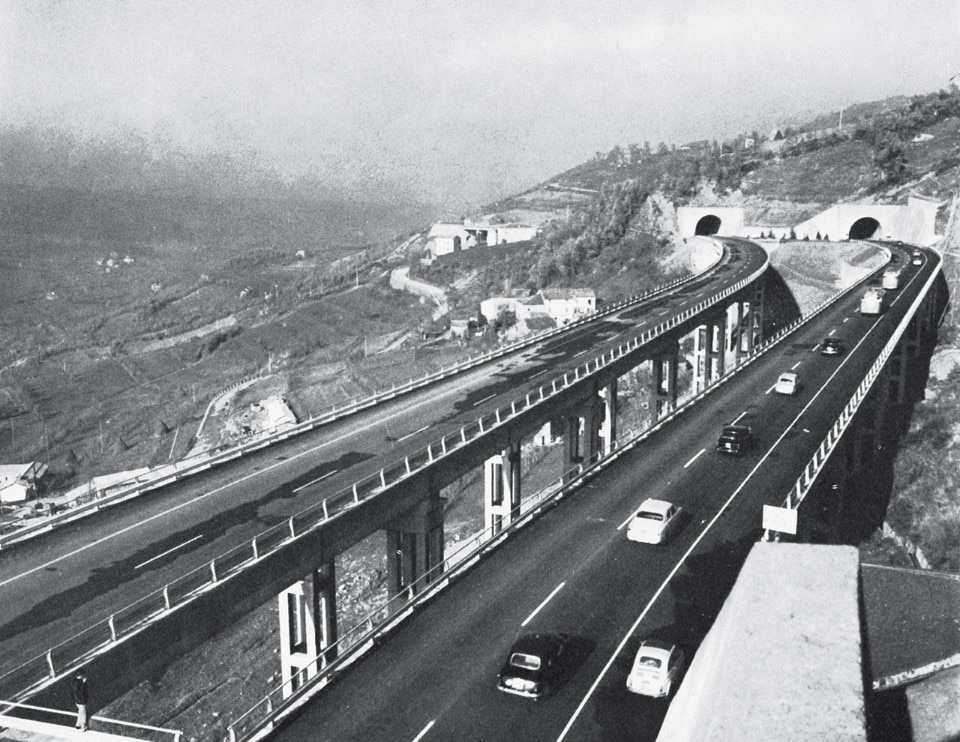

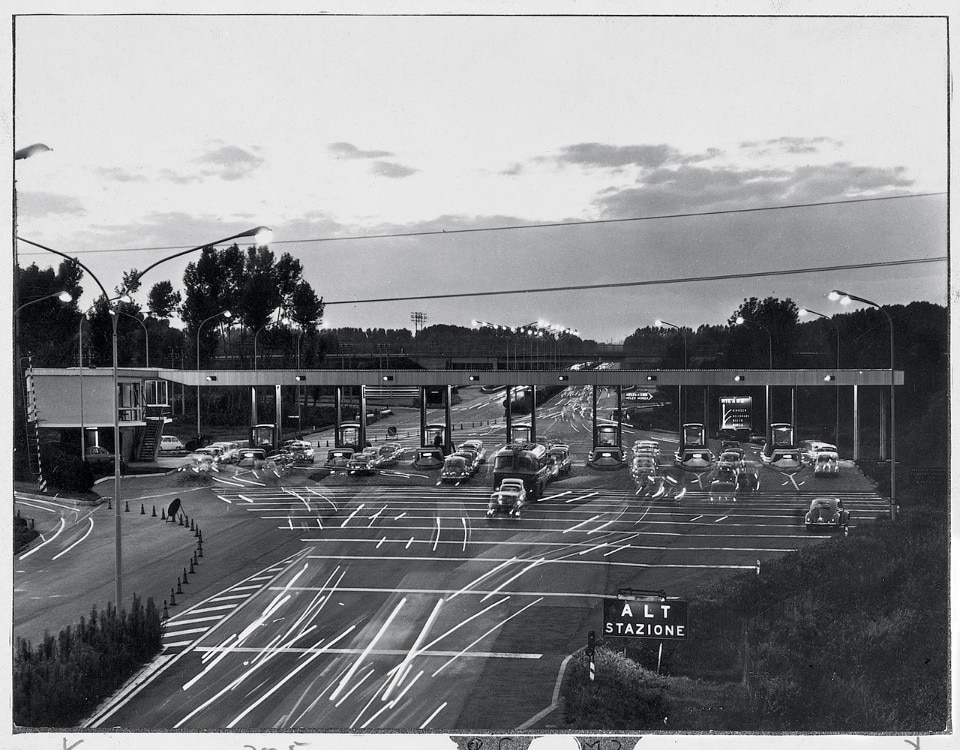

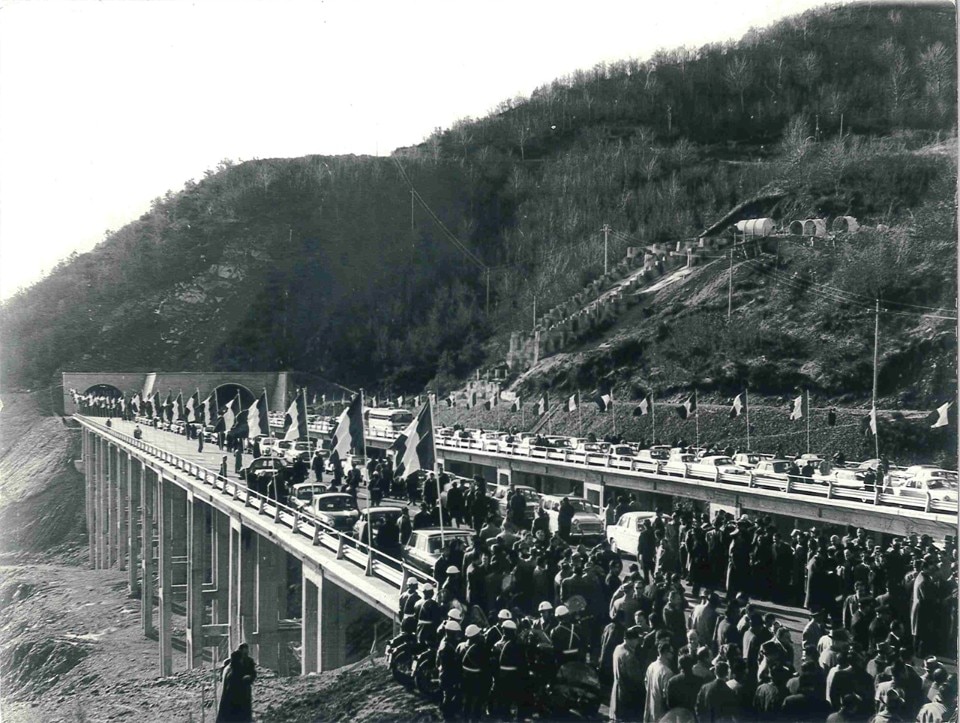

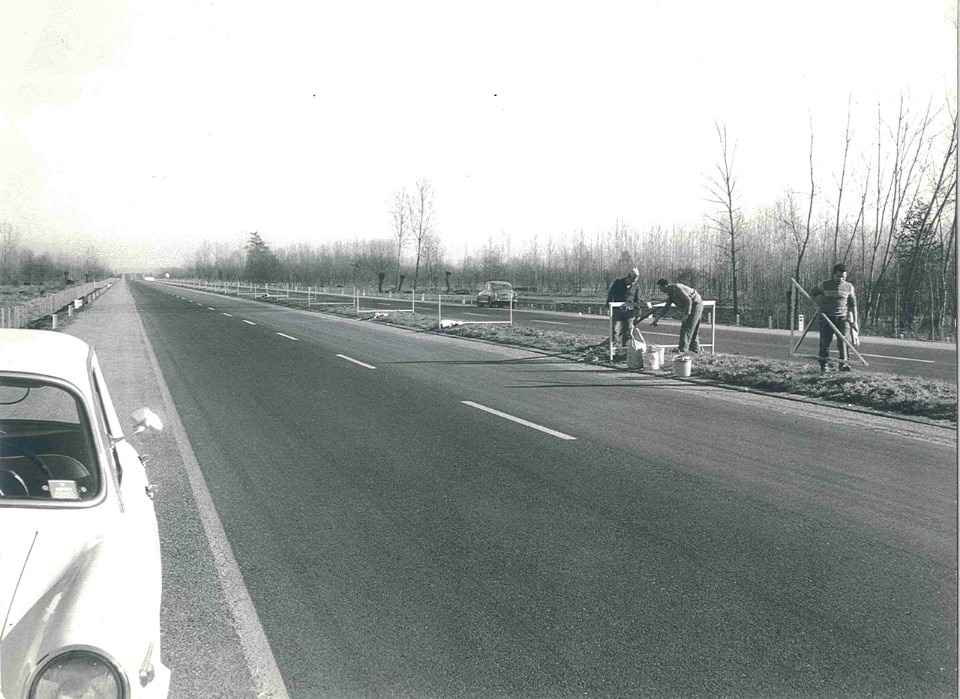

Eight years pass between the laying of the first stone, on May 19 1956 in San Donato Milanese, with President of the Republic Giovanni Gronchi, and the inauguration of the 764 kilometers between Milan and Naples, on October 4 1964, by Prime Minister Aldo Moro. Never since the end of the war had so much money been invested on a single infrastructure: 100 billions of Italian lire, which materialize in 113 bridges and viaducts, 572 flyovers, 38 tunnels and 57 junctions.

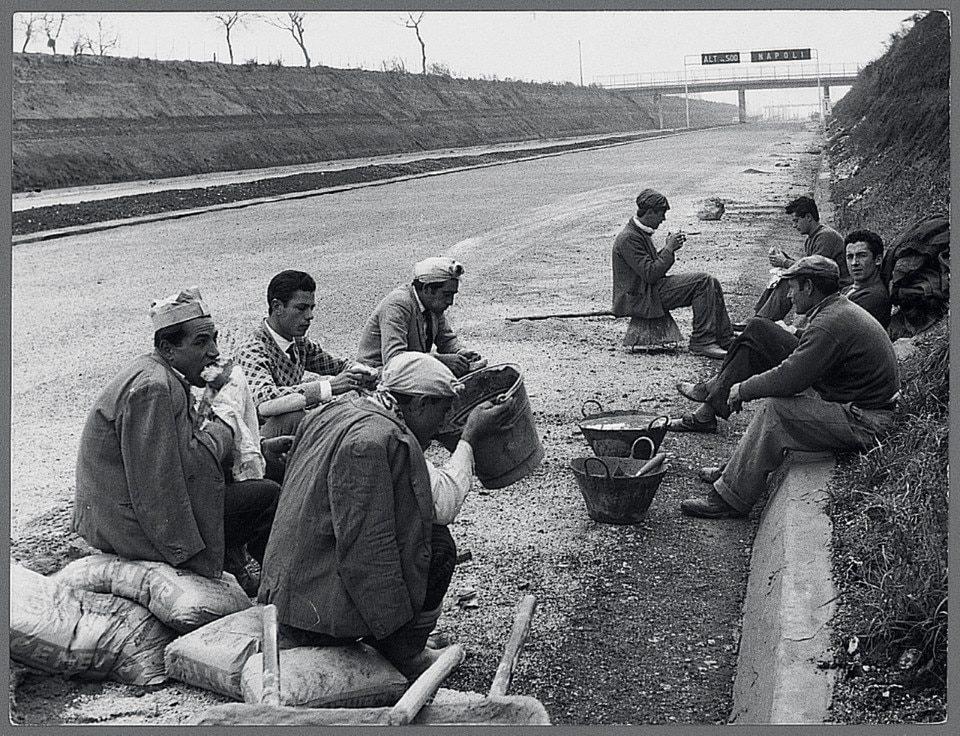

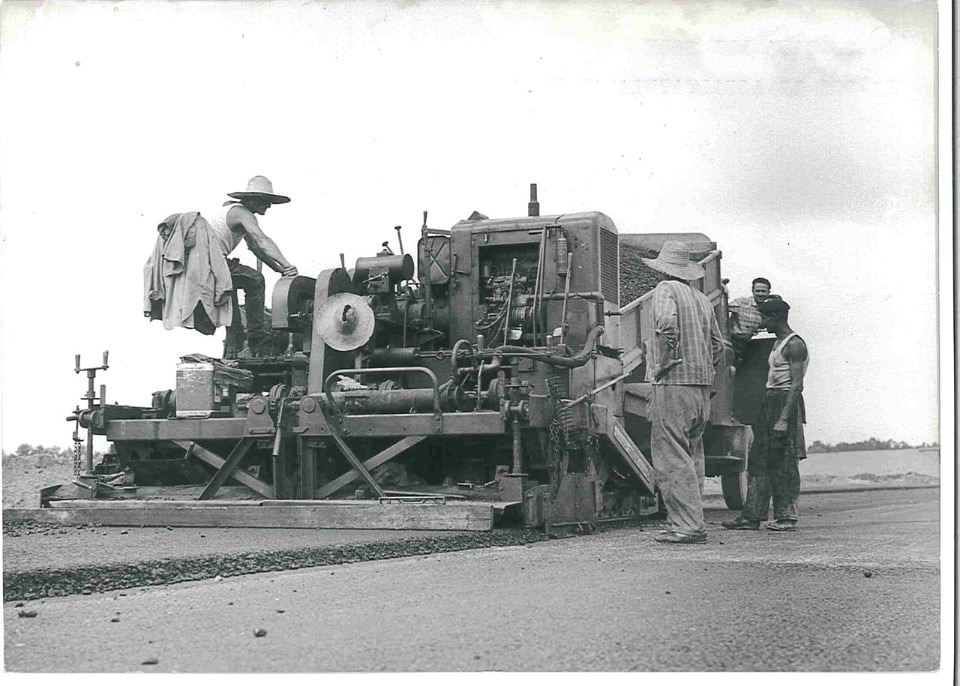

Under positive and short-lived circumstances the country’s authorities, minds and manpower team up for the realization of an inevitably collective enterprise. The IRI, a public body, launches the project that is rapidly endorsed by four large scale private companies – Agip, Fiat, Pirelli and Italcementi – which understand its potential, also for their own interests. The baseline intuition is Puricelli’s, the initiator of the Lakes region highway, but other engineers attend to its implementation: Francesco Aimone Jelmoni, the author of a comprehensive preliminary project, and Fedele Cova, the CEO of Società Autostrade per l’Italia, who coordinates the operations. He is the one who suggests dividing the road into few-kilometers lots, to simplify working sites management but also to involve as many contractors as possible.

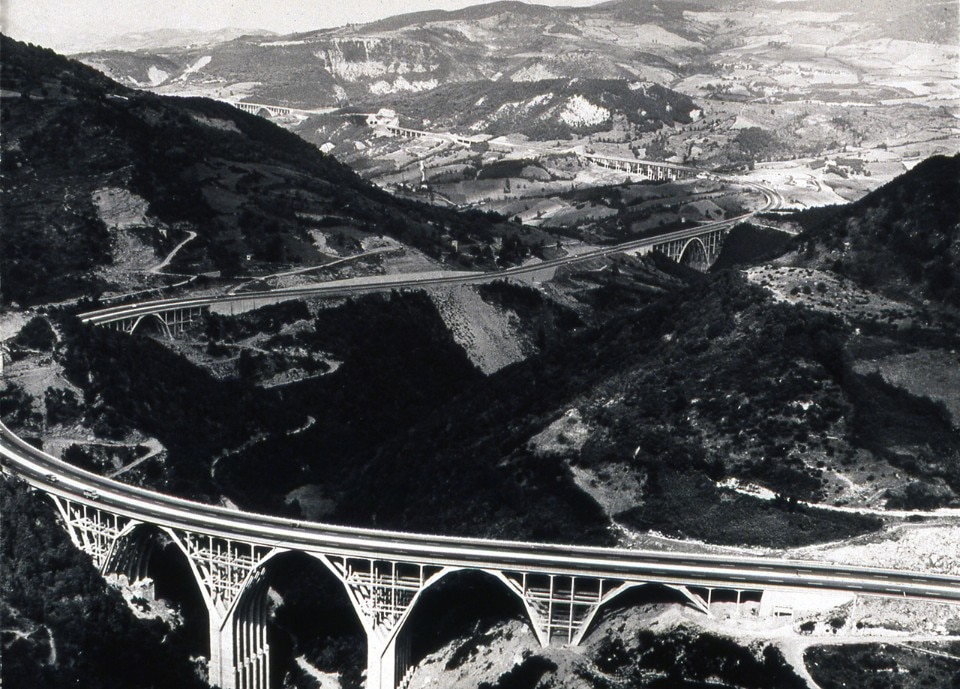

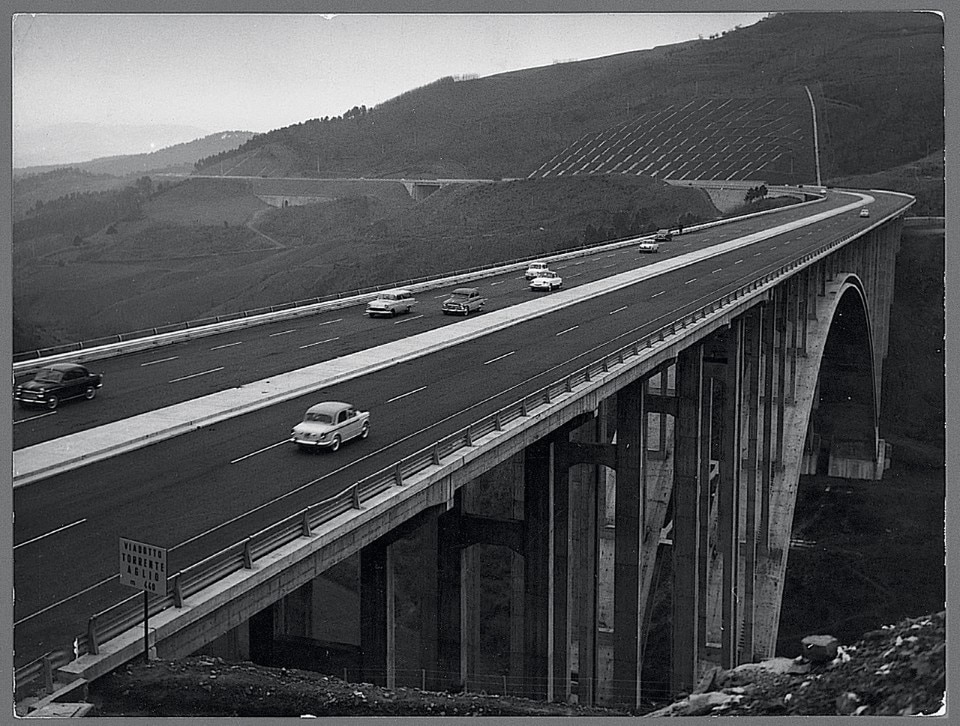

The Autostrada del Sole impresses in the first place as an artefact, for the technical, material and aesthetic qualities of its parts. While construction is still in progress, several of its bridges are shown at New York’s MoMA, in the 1964 exhibition about Twentieth Century Engineering. This is a well-deserved acknowledgement for a series of structural experiments dared by Silvano Zorzi – he designs, among other things, the prestressed reinforced concrete bridge over the Po river in Piacenza, that is at the time the largest in Europe of its kind – by Riccardo Morandi – who works on most of the viaducts on the complex Bologna-Florence section – as well as by Giulio Krall, Arrigo Carè and Giorgio Giannelli, Carlo Cestelli Guidi and Guido Oberti.

The Church of San Giovanni Battista in Campi Bisenzio (1960-1964), one of the most organic architectures by Giovanni Michelucci, is part in all respects of the highway’s project, and is conceived also as a tribute to workplace victims. Even before the monumental temple, another highly recongnizable architecture, way more original for its shapes and program, surfaced from the highway: it’s Europe’s first bridge-type autogrill, designed for entrepreneur Pavesi by Angelo Bianchetti and inaugurated in 1959 in Fiorenzuola d’Arda.

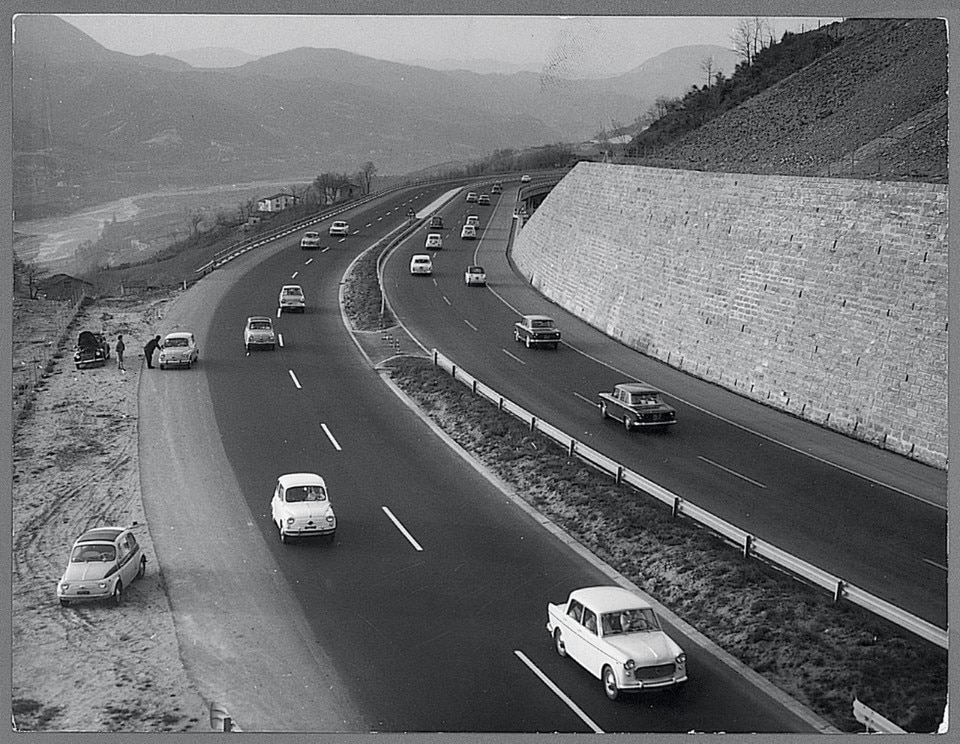

This mass of constructions of different looks and nature is grafted within the Italian territory, which many consider as unique for its “excess of geographical, anthropological and cultural thickness” – this is for instance the opinion of Giacomo Polin, an architect and the author of Il paesaggio dell’autostrada italiana (Autostrade per l’Italia, 2011). This is not a desert that civilization conquers thanks to the highway, but rather a palinsest of signs of different nature and from all ages, with which the infrastructure relates willingly or reluctantly. The passing appearance of the village of Orte, so close to the lanes to actually appear as suspended over them, right to the north of the namesake tollgate, is a representative example of a proximity and a conflict that repeat countless times along the track. In the Bel Paese’s stratified territory, the Autostrada del Sole is sometimes a sensible and other times a violent insertion, whose transformation potential reverberates well beyond its physical boundaries. It implies a global reorganization of the road network, with several national and provincial routes turned from major thoroughfares to “panoramic” paths. In parallel, settlements with similar urban histories see their destinies and their appeal being redefined on the basis of their distance from the closer toll.

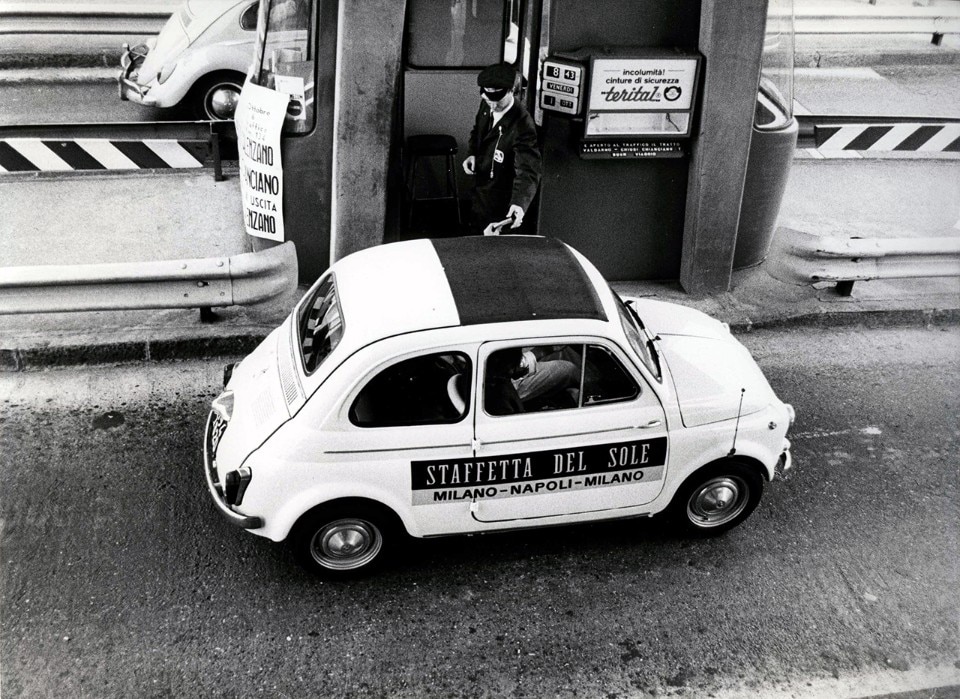

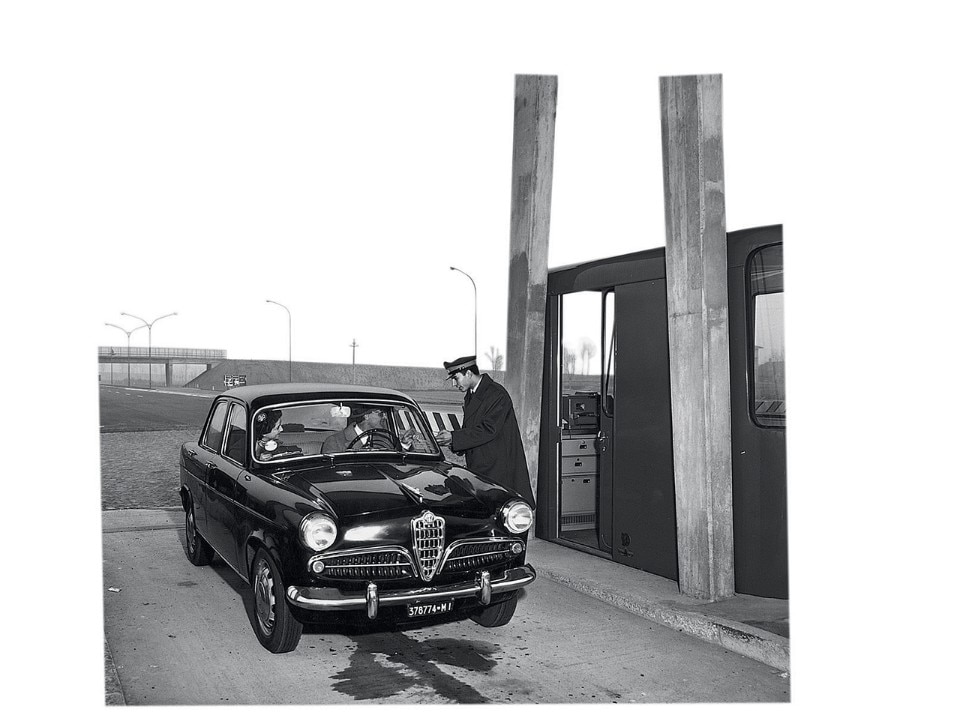

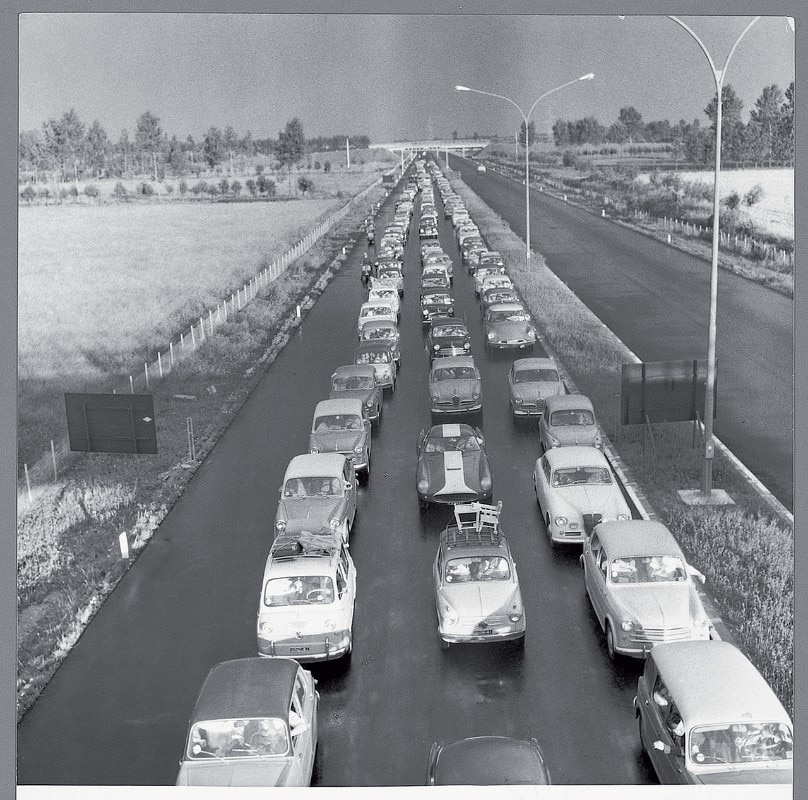

Besides the profound material and environmental transformations that it generates, the Autostrada del Sole deserves to be described as a cultural object, at the crossroads of multiple themes and imageries. Its construction is accompanied from the very beginning by the narrative of the connection between North and South, between the most industrialized part of Italy and the problematic Mezzogiorno – the most vigilant readers will certainly spy a patronizing accent in the “del Sole” nickname, hinting primarily at a North-South trajectory, escaping the foggy winters of the Po Valley. Furthermore, its vicissitudes are strictly tied to the country’s mass motorization: precisely in 1956 FIAT launches the 500 – while the 600 is from 1955 – and in the same year Gianni Mazzocchi founds Quattroruote, a seminal magazine dealing not just with cars but with a broader culture of the automobile. The journal gives ample space to the Autostrada del Sole, stressing the link between hardware and software, between the modernity of infrastructures and of the cars circulating through them.

Precisely the contradictions of Italian modernity – or better modernization – are the core of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s well-known analysis of the ambiguous “technocratic language” employed by Moro to comment on the inauguration of the Autostrada del Sole. Which, for its part, in the following decades stars both as a symbol and as a location in such a number of movies that they would deserve to be dealt with separately. A rushed and incomplete selection will point out the Mario Missiroli’s Bella di Lodi races along it in 1963, that Furio and Magda’s tragedy in Carlo Verdone’s Bianco, rosso e Verdone unfolds here in 1981 and that the doomed Rosalba, the protagonist of Silvio Soldini’s Pane e Tulipani is abandoned here in a service station in 2000.

As expected, through the years the Autostrada del Sole has been largely modified, extended and even doubled between Bologna and Florence, where drivers can now choose between a brand new “Direttissima” and an ancient “Panoramica”. Similarly to other Italian infrastructures, it embodies the paradox of being at the same time obsolete, for the type of mobility that it supports, historical, for its age and for its final recognition as a monument, and still vibrant and topical, for the flows that it keeps hosting every day through Italy. Over the next six decades, when other revolutions are likely to happen in the field of transportation, the Autostrada del Sole will remain an interesting case study to evaluate how the dialogue between heritage and functionality will evolve in the management of large-scale infrastructures, which today’s world inherited from the 20th century.