As I hadn’t even managed to turn the camera on, Bnoh promptly climbed up the tree and started the maintenance of an embryonic bridge growing around 20 minutes walk from the village. Bnoh Buhphang is a 42 years old Khasi man who has been living in the village of Nongblai, in Northeastern India, for the last 20 years. He works mainly with bamboo, and creates artifacts to be sold to the market. Indeed, not only he weaves bamboo into baskets and carves the traditional Khasi flute – being apparently the most talented flute manufacturer in the village – but he can also build traditional bamboo bridges. Nevertheless, his specialty relies in the construction of one of the wonders surrounding Nongblai: living root bridges.

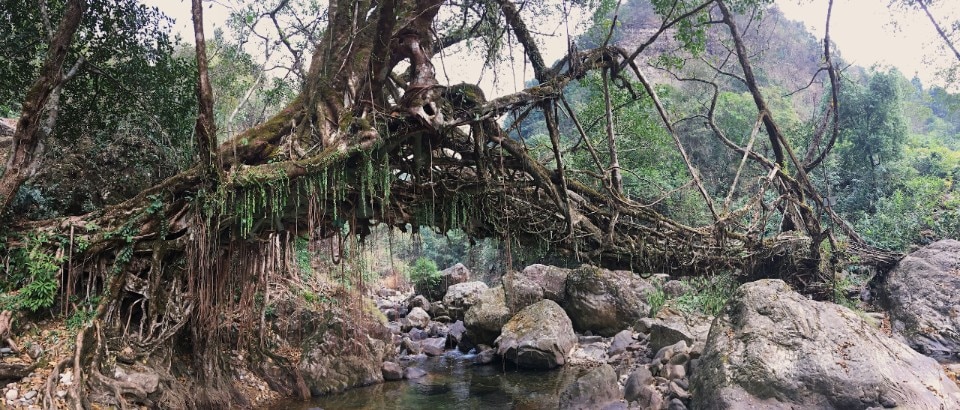

As scholars of Ca’ Foscari University, Venice, we are conducting a research on Khasi culture in order to understand how living root bridges are built and how they are entangled with the local cultural habitus. To start a living root bridge is not an easy task, and its maintenance is just as difficult, especially at the initial stages of construction. Bnoh is one of the few men in Nongblai who can take care of it, and he generously allowed us to assist this practice. He told us he would have carried on the seasonal maintenance of a shy new emerging bridge just a few years old. So there we were, in front of a confused set of suspended aerial roots of a rubber tree rising up on the clefts above a small river. Just like an equilibrist, he began walking on the core aerial root fixed in the ground as he started throwing, pulling, probing and knotting together other roots helping himself with a long bamboo stick. A foresight he could apparently solely envision. Within the next 20 years or so, if he will continue this maintenance practices with the same dedication, helped by the other men of the community, this will be another living root bridge to be accounted next to the 18 already existing in the village area.

Nongblai is a small village laying at the bottom of a valley surrounded by steep hills covered with forests. It raises in the East Khasi Hills, in the state of Meghalaya (India), close to the border with Bangladesh, one of the rainiest regions in the world. Reachable only by foot from the closest main road with a walk down the slope counting about 8,000 steps, it is inhabited by more or less 250 souls from the matrilineal War-Khasi tribal group. The life of the villagers is closely bounded with the surrounding forests, since many families’ sustenance rely on the forest’s land for rising food and harvested plants to be exchanged at the market. To endure their activities, it is fundamental for them to walk easily in the woods and to cross the steep clefts and rivers. However, whilst in spring rivers flow peacefully, during monsoons waters get stronger: this often generates difficulties for the villagers to cross over traditional bamboo bridges or modern cement ones, since they can be easily pulled out by the current’s strength.

While animals base their viability in movement like us, plants being sessile living beings guarantee their subsistence in growth. Therefore, if we consider resources as living entities, the only way to make something out of them is to set a scaffold to start a “dialogue” with them

Since centuries back, the need to overcome this problem of river crossing has led Khasis to develop alternative strategies in bridge construction, developing what are now largely known as living root bridges. Spotted for the first time as a mere curiosity by the British botanist Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker in his sketchbook at the end of the XIX century, living root bridges have gone unnoticed even by the local population until a couple of decades ago. Indeed, before 2003 the whole War-Khasi area has been basically unknown to the world until a village in the region won a prize held by Discover India magazine for being the “Cleanest village of Asia”. As the event fueled tourism and enhanced a deeper interest in local amenities, living root bridges have seen an enormous increase in popularity as well, becoming a must-visit highlight for nature lovers and adventurous trekkers. Built from the aerial roots of rubber trees (Ficus elastica), the bridges mainly unfold upon high cliffs or at the bottom of steep valleys on large riverbanks as they result extremely varied in terms of shape and dimensions.

Although being both useful and integral parts of the War-Khasi landscape, surprisingly very little is know about the traditions, beliefs, construction practices, and most of all botanical knowledge regarding these incredible artifacts. Our research first started exactly here in Nongblai as it remained pretty much off the beaten track by tourists. Moreover, its 18 bridges offered us the ideal site to observe the phenomenon of living root bridges.

What emerged from our fieldwork was the different approach War-Khasis have in their relationship with nature when compared to ours. Khasis traditionally are an animist society, where every element of nature is for them “alive”, and thus able to act intentionally, following what Philippe Descola pointed out in his notorious book Beyond Nature and Culture in defining animism. To use resources from the forest implies then establishing a fair exchange between humans and resources themselves. This happens as well when dealing with rubber trees: some stories collected in the East Khasi Hills tell about the power of Ficus elastica, especially in being potentially able to steal the soul of the one planting it if his shadow would accidentally fall in the hole where the rubber tree is positioned.

This brings us to another consideration: if resources are alive, in order to understand the interchange between man and plants in constructing living roots bridges, the basis of our Western conception of resources needs to be reviewed. In fact, our economic tradition sees resources as scarce passive entities, which are strategically used by humans for their ends, as Lionel Robbins stated back in 1932. Nevertheless, living root bridges are all but passive: they are living beings acting and behaving in a way that apparently only the remote culture of the War-Khasis has been able to observe and to engage with, building infrastructures that grow more solid and stronger year after year. Ficus elastica acts and behaves as a plant would do, and, as recent advancements in Botanic have shown, plants present very different survival strategies than ours (a nice introduction to plant biology is given by Francis Hallé in his book In Praise for Plants, while much can be learned about behavioral botanic looking at Stefano Mancuso’s life-long research).

For instance, while animals base their viability in movement like us, plants being sessile living beings guarantee their subsistence in growth. Therefore, if we consider resources as living entities, the only way to make something out of them is to set a scaffold to start a “dialogue” with them. So, the question is, how did Khasis manage to develop such knowledge on plants? The answer is not there yet, as it is part of our research, still at an early stage. What is clear, though, is that understanding human-plant interaction in the construction of living root bridges might give us a tool to think the future of our own environment. Is this “interspecies urbanism” possible outside of Nongblai? If our traditional urban environment has led us to a sort of “plant blindness”, on the contrary, Khasis’ folklore, beliefs, and traditions have allowed them to really see and know plants in their milieu. This is especially true observing the fruitful interchange War-Khasis have with Ficus elastica, with which they are able to grow marvelous lasting infrastructures harmoniously embedded in their own native environment. Can we develop similar alternative construction paradigms? Observing Bnoh doing maintenance is certainly a key, and it allowed us to see these extraordinary living beings from his Khasis’ eyes: a sprouting set of suspended aerial roots to be grown with his hands and the ones of his fellows, a collective dialogue with the plant that only future generations will really appreciate and that will hopefully continue to endure in time.

Credits:

These considerations are an extract of my PhD research thesis in Management at Ca’ Foscari University, where I am conducing research along with Professor Massimo Warglien. As many people are involved in this project, I would like to thank in sparse order who made my field work in Nongblai possible, namely Professor Desmond L. Kharmawphlang and all his family, Miss Manhakani Nongrum and all her family, Headman Wan Shai and all the members of Nongblai Eco Development Tourism Society as well as all the people I had the chance to meet in Nongblai, with a special thank to Ban and Biang who guided us around. To conclude, a sincere thanks goes to Mrs. Anna Gerotto, whose observations and ideas are key in the development of the project.