Some practices bring together certain fields of design that are seemingly unrelated. Like participatory design, an innovative approach to the design of new products and ideas with a remarkable focus on the design phase. This approach is used in architecture, but also in the field of game design. ‘Bottom-up’ game design has taken different forms over the year, narrowing the gap between those who buy the game (consumers) and those who design it (producers), and forcing all people involved in the game development process to constantly interact with each other.

Although the level of customization is one of the most important aspects of game design in recent years, the participation of users in the design process has far more ancient roots. One of its first examples might be modding, a term that basically sums up all those ways in which the player can make modifications to a game that was created by someone else and wasn't originally meant to be modified. Modding can take many forms, depending on what part of the product you decide to change, and what you want to achieve. They can purely involve the aesthetic component of a game (the appearance of the characters, the environment that surrounds them) or its mechanics (the addition of more options during the gaming experience, the user interface), going from a small and almost invisible modification to a total revolution compared to the product sold in the shops.

The representation of space as a way to metabolize it

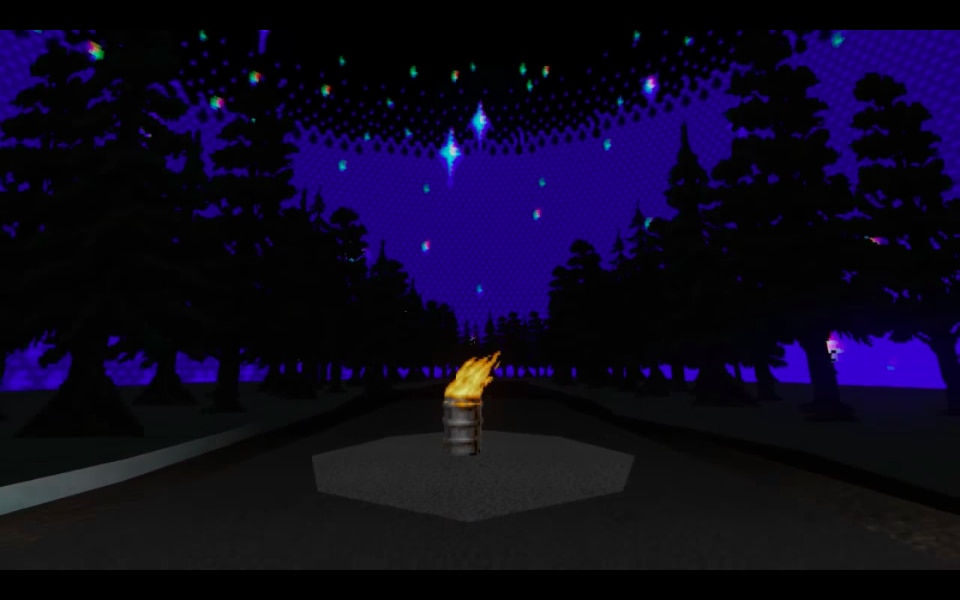

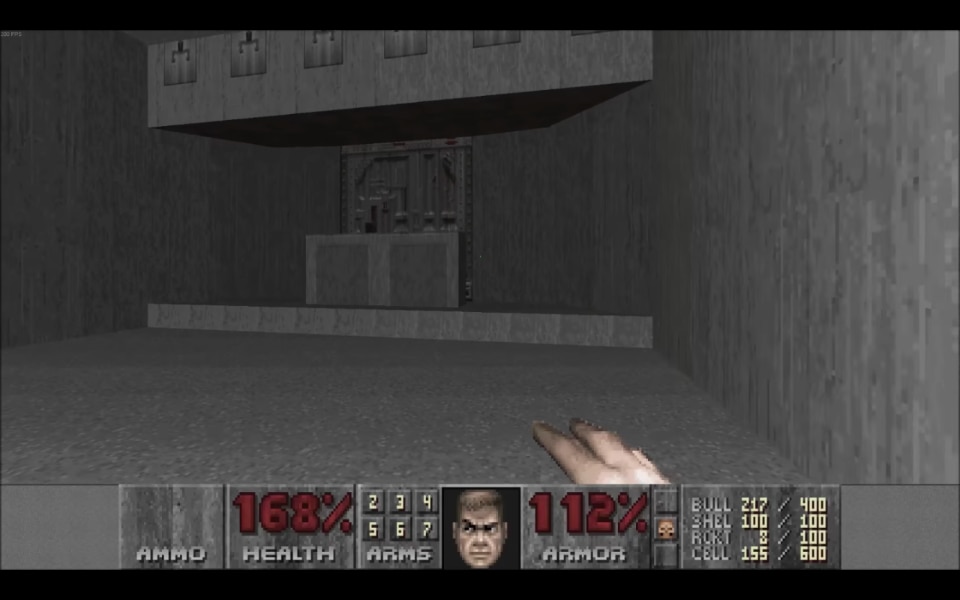

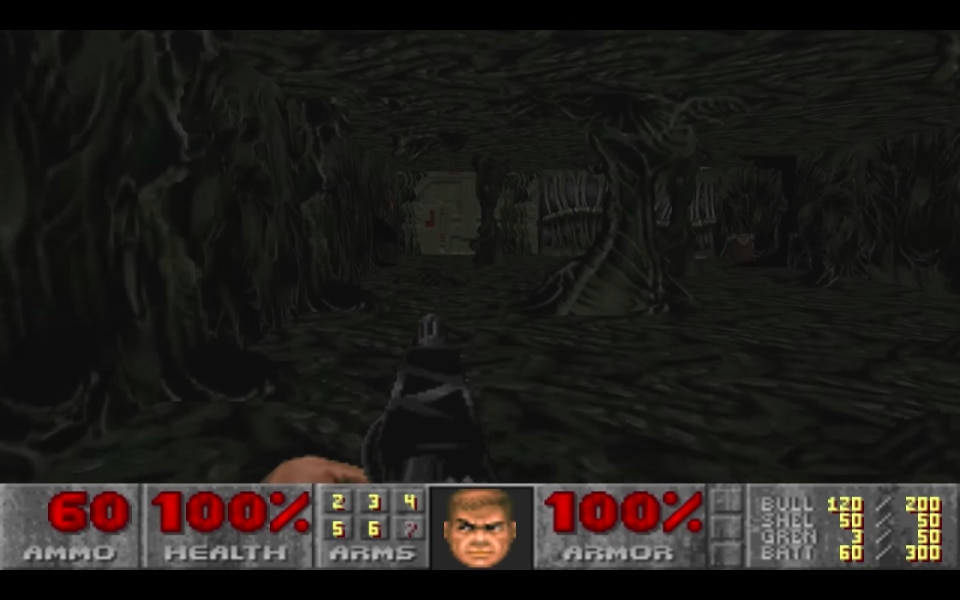

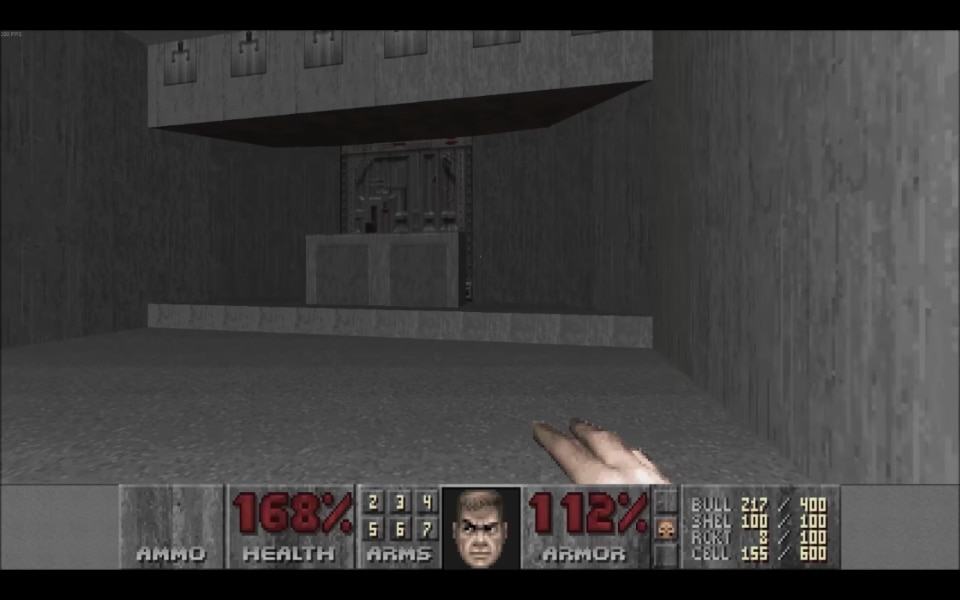

Giancarlo de Carlo said that “the architecture of the future will be characterized by an increasing user participation both in the organization and in its formal definition”. The interaction between real world, virtual world and architecture has greatly influenced the realization of mods. For example, a user called 1337 Doomer took inspiration from brutalist architecture, which is perfectly in line with the native environment of the game, to realize Brutalist Doom, a gaming experience characterized by loneliness and alienation. In this new version, an architecture conceived to optimize the everyday life of a multitude of people is totally transformed: you find yourself all alone inside an enormous and indefinite space, full of threats around every corner. The surfaces become nightmares as grey as exposed concrete, disproportionate environments, too big for just one person. In that immense grey space, colours remain the exclusive prerogative of the original monsters of the game (which continue to exist and haunt both the narrow corridors and the immense open spaces), with blood and violence that turn out to be even more overwhelming.

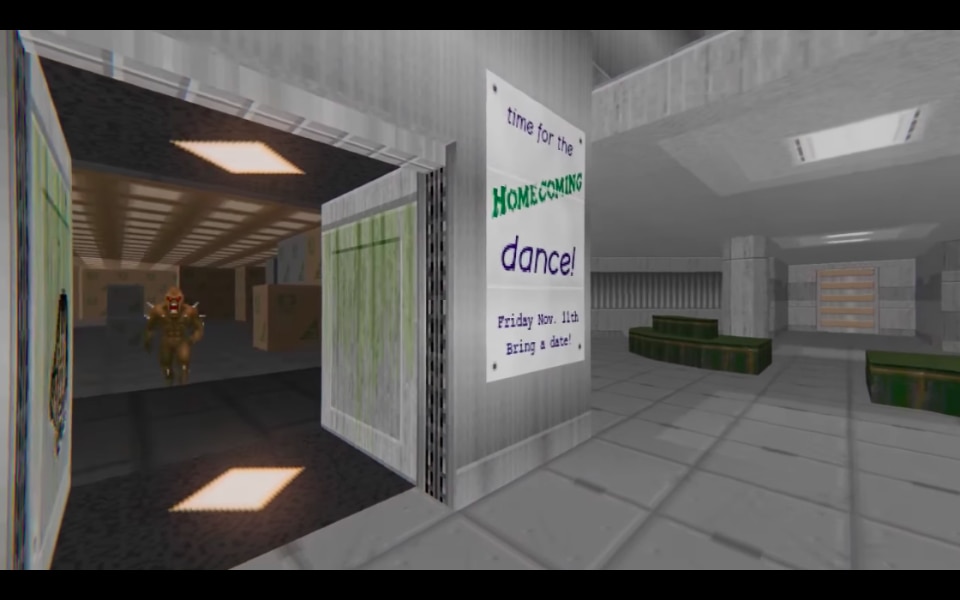

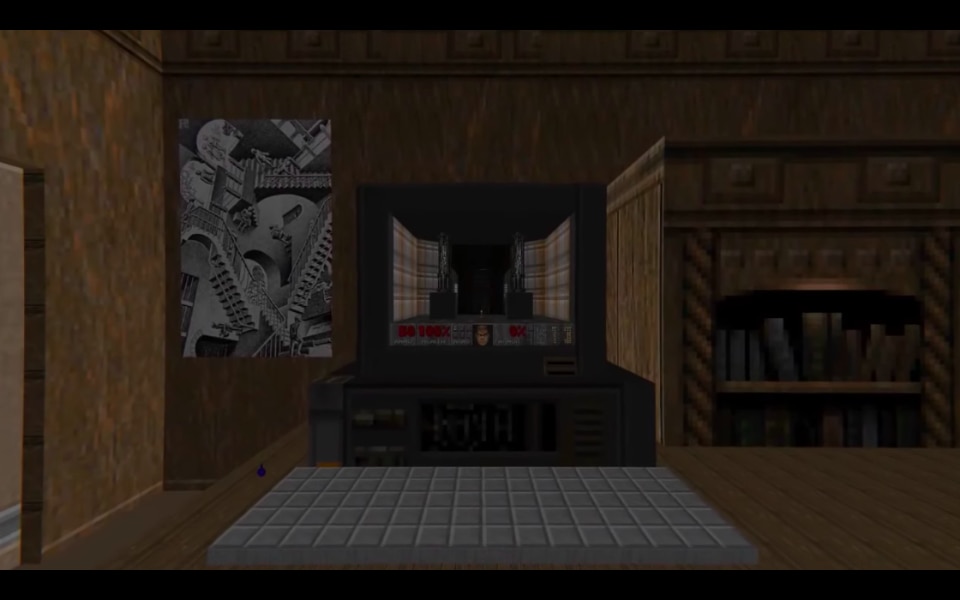

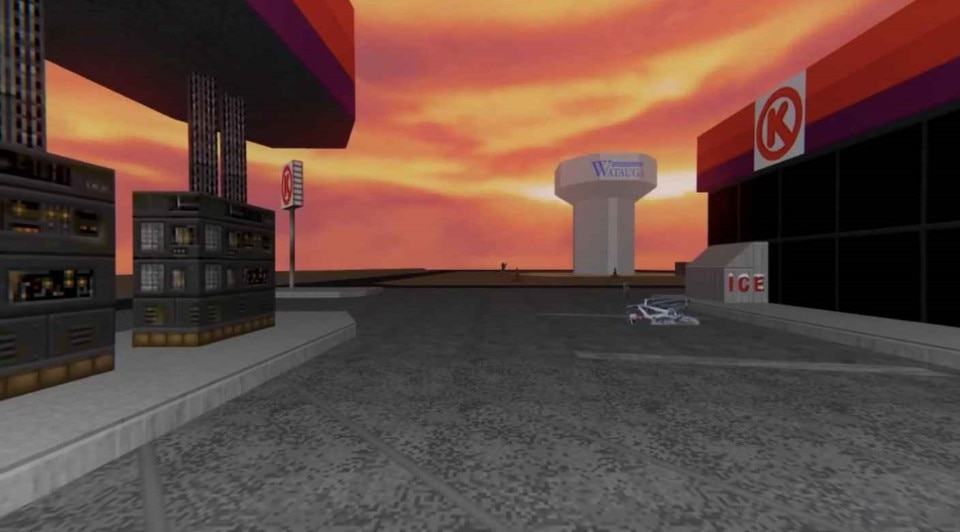

In Autobiographical Architecture, a user called JP LeBreton used Doom 2 to tell his daily life story. In this specific case, we are not talking about the formalisation of universal stylistic features, but about the painstaking observation and reproduction of an autobiographical experience, and then sharing it with other players. There is nothing measurable anymore, there is no longer “style” per se, but a fictionalized tale aimed at offering a narrative experience more than a mere visual suggestion. As you can easily imagine, a lot of mod inspiration came from movies, books and comics, from Aliens TC – which was the first total conversion of Doom, rewriting a game world inspired by James Cameron's Alien (1986), to The Darkest Hour (seven maps inspired by Star Wars) Batman Doom and so on, until Paranoid, a conversion inspired by another (famous) video game, Half Life. All these worlds were designed by users and made available to others so that everyone could enjoy them.

Doom, a game designed to be modular and customizable

The Doom series, one of the most iconic and long-lived video game series in the history of video games since the 1990s, is one of the most interesting examples of modding and participatory design in the video games world, because it was one of the first games to be disassembled and reassembled in an impressive way. In 1993, Id Software, a Texas-based video game company, released the original Doom, which was played by almost twenty million people in just a couple of years. Remembering the success of their previous game, Wolfenstein 3D, which some players had attempted to modify, lead programmer John Carmack decided to make it open source, in order to make it easier for players to modify it.

The architecture of the future will be characterized by an increasing user participation both in the organization and in its formal definition (Giancarlo De Carlo)

For those who don't know, Carmack is one of the main supporters of copyleft, an innovative copyright management model that strongly influenced the hacker culture and ethics of the 1980s and 1990s and that allows users to distribute free modified versions of basic products. For this reason, it doesn't come as a surprise that he decided to leave in the WAD file containing all archive files of the game data, such as graphics, sound effects and music. He offered a modular and easily editable solution for the consumers.

This choice has certainly greatly simplified the modding experience, not only because it has provided a clear and practical example to follow when processing files, but also because it has allowed anyone to start at the same level. This led to the creation of shared tutorials with instruction packs that made it easier for everyone to make any modifications to the game.

Time and Landscape: Mods between Neoclassical and Baroque

An interesting aspect is the antithetical link between the frenzy of the game (in which one must basically face an endless horde of demons while going from a point “A” to a point “B”) and the time needed to better appreciate the architecture or the space. Looking at the past and wanting to make the most universal examples possible, one can consider the transition between the Baroque period – in which the way of moving mainly on foot through the city allowed people to observe it by focusing on details, urban scenes and points of interest – and the advent of Neoclassicism, when everything began to go faster and faster, bringing architecture and urban solutions towards more essential and less decorative forms.

When playing Doom, speed is an essential factor, combined with good reflexes and responsive intuition. To be clear, when online resources such as maps and guided routes were not available, players would draw ideal lines on sheets of paper to get in and out of maps in a short time and use as few resources as possible. And yet, it was from that same generation of players that the mod phenomenon was born, with all the graphic attention associated with it. Perhaps, the charm of the whole operation is all here: in the choice to subvert the rules written by others, each taking its own time. A lesson that started from below and reached the official development. In this sense, in the new chapter Doom: Eternal, old and new players face an ever-increasing frenzy, while advancing in spaces designed with unprecedented precision, more and more credible and consistent.