After 15 years, Mirko Zardini has left the direction of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in Montreal. Our conversation – full of quotes by Gordon Matta-Clark and Clint Eastwood – took place in his home in Milan, where the bookcases seem to be holding up the ceilings.

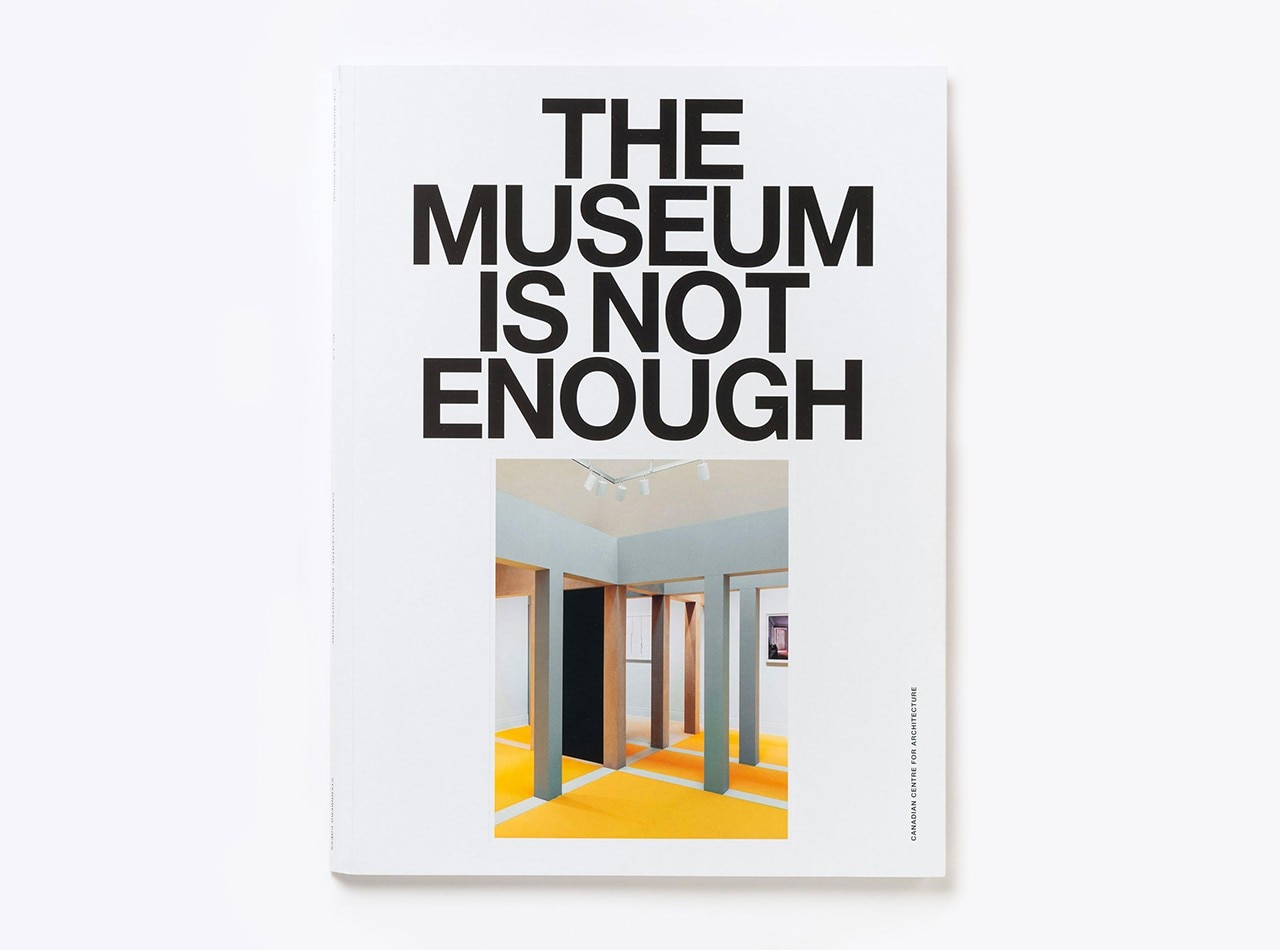

The chat revolved around a fundamental question: how does one manage to rethink an institution when “the museum is not enough”? – to quote the title of the latest publication on which he worked with Albert Ferré, Francesco Garutti, Jayne Kelly and Giovanna Borasi, now director of the CCA.

In recent years, Zardini had extended the range of action of the institution, by imagining and developing ways to revive the relationship between architecture and contemporary society and showing that sometimes the most important characteristic of being a good director is, actually, not wanting to be a director at all.

What are you going to do now?

I’d like to go back to research and to explore new themes. When I arrived at the CCA, I brought with me, and then developed thanks to the activities of the Center, an enormous pool of ideas that I had come up with in previous years, through teaching, research, projects, books and exhibitions. Now I would like to learn more about new topics. I am working on a course at Princeton that is already part of this research. “Behind the Objects” wants to analyze the different and often-time contradictory stories and habits that corrode the supposed neutrality of elements such as the solar panel, the bicycle, the stairs, the barbed wire.

Will you move back to Milan?

I think so. I’ve always lived in different places, between Milan and Zurich, Milan and Lausanne, Milan and the United States, Milan and Canada. I have never really left this city, which has always been a reference point for me, for better or for worse. When people asked me where I lived, I always replied “I live in Milan but I work in Montreal, I commute”.

Why did you decide to no longer be the director of the CCA?

I never wanted to be the director of anything at all. I accepted this position because the CCA offered me the opportunity to develop a debate on contemporary architecture, during a time of crisis and profound transformation. Today this debate, which started 15 years ago, is almost over, and I take it as a sign that it’s time for me to start new research and new projects. I am glad that Phyllis Lambert and the Board of the CCA have chosen Giovanna Borasi as the new director: we had already worked together before. I think that this choice will bring a nice change around here.

How did you develop the CCA working method?

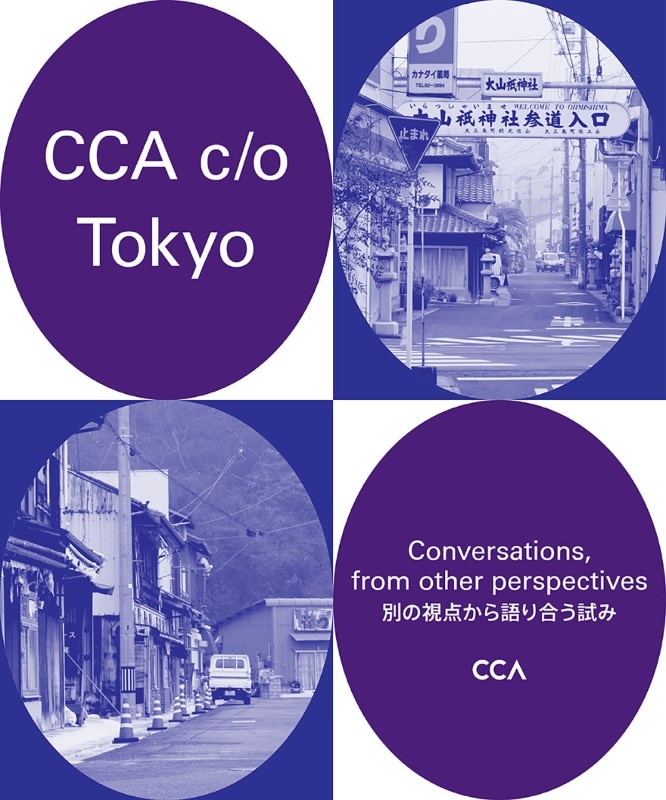

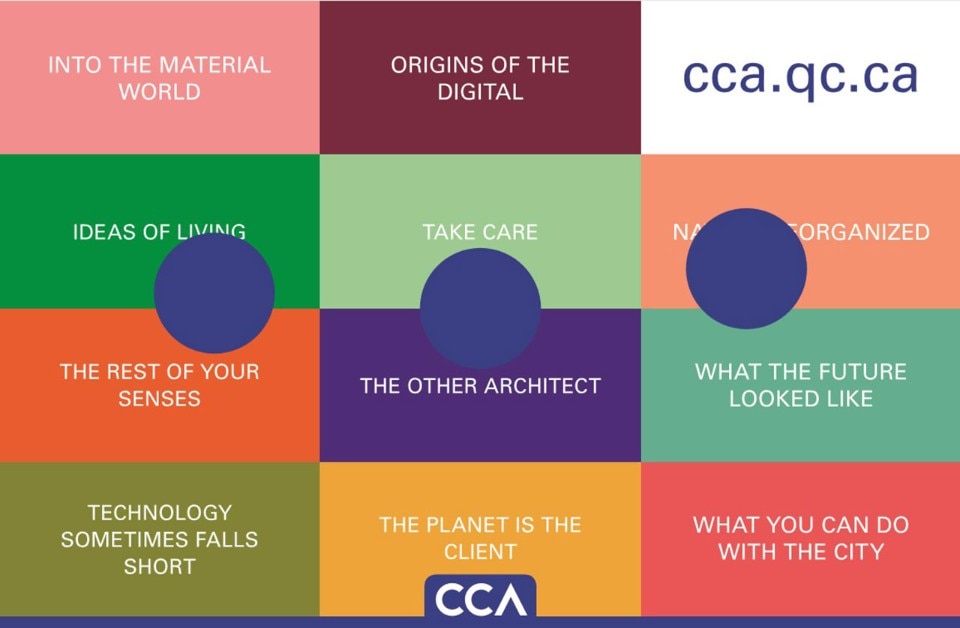

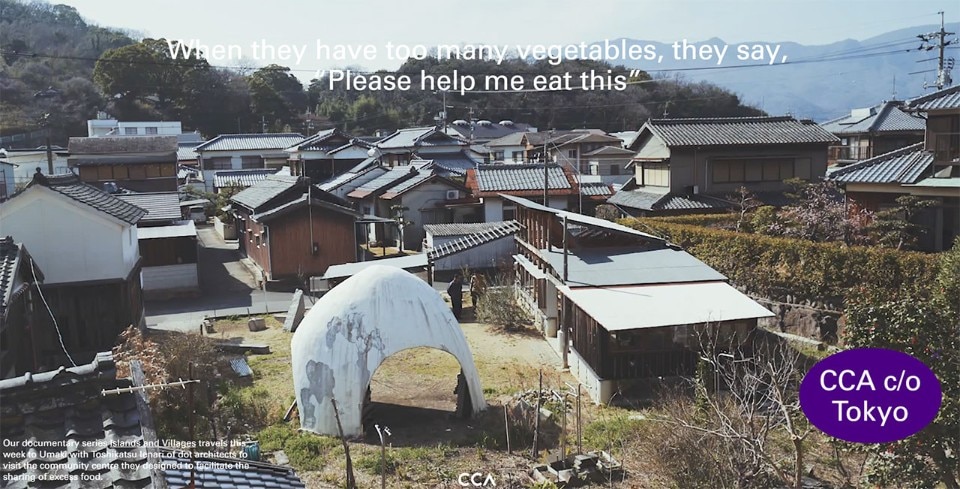

Since the beginning, I tried to create an institution that was also anti-institutional, able to straddle the official and recognized architectural culture, the reflections and projects coming from the alternative cultures, and from those that are still considered “peripheral cultures”. Actually, there’s no such thing as periphery no more, but different voices coming from different places and contexts. We tried to capture these voices and reflections by developing research activities together with architects and curators in different cities, including the CCA/co program (first in Lisbon, then Tokyo and in the future Buenos Aires). These new extensions, or nerve endings, have helped us to enrich research, curatorial and editorial works that underpin the CCA’s activities. We have also changed the way we work within the CCA. The different processes typical of the institution, like research, exhibitions and publications, acquisitions and cataloguing: instead of taking place, as often happens, in a precise chronological sequence, they take place simultaneously, starting with my first exhibition at the CCA, “Out of the Box” (2003). In this case, with the archives of Cedric Price, Aldo Rossi, James Stirling and Gordon Matta-Clark, and then in other projects such as “Archeology of the Digital”, the processes of acquisition, and research on archives and projects overlapped with installations. The texts and captions were being constantly updated, as the research progressed.

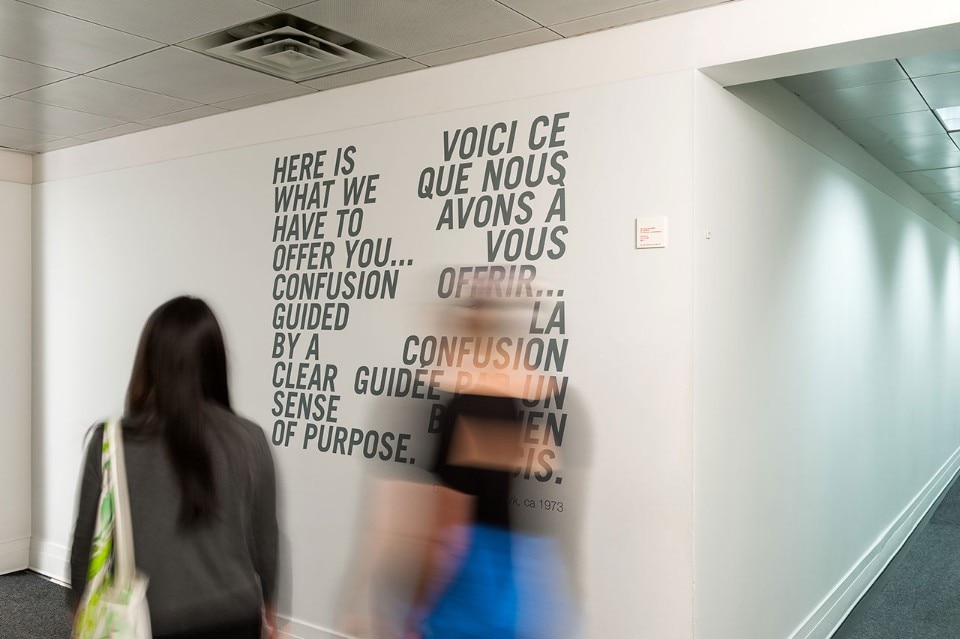

You placed a quote by Gordon Matta-Clark at the entrance of the CCA: “Here is what we have to offer you in its most elaborate form – confusion guided by a clear sense of purpose”. Is that the spirit of the institution?

Yes, you don’t always know the stakes involved, especially during times of profound transformation – social, cultural, political, economic and climatic – like the ones we are experiencing now, but you always choose to move in a particular direction, based on your objectives and values. I wanted to offer different tools in order to reflect on architecture, urban planning, landscape, and apply these observations to contemporary problems.

How does this approach compare to the previous CCA approach and what were your objectives?

The CCA was founded in 1979 by Phyllis Lambert. This was a very important time, with many institutions dedicated to architecture being founded, such as the NAi in Rotterdam, the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt, the Getty Centre in Los Angeles and, also in 1979, the International Confederation of Architecture Museums (ICAM). All these institutions wanted to draw attention to architecture as an autonomous discipline, “architecture itself”, as Sylvia Lavin would say. My aim was to put the debate back into context, thinking of architecture as a way of looking at society, and society as a way of looking at architecture.

What’s your audience?

The audience does not exist in itself, each institution builds its own audience, or rather its own different kinds of audience.

What did you build, then?

Ours is a conversation project that aims to involve different audiences, all interested in taking part in new debates on architecture and contemporary society. The online presence is a fundamental component to complement publications and books, because it expands the curatorial and editorial strategy and offers access to the CCA’s collection, research and activities to a geographically dispersed audience. The investments that led to the creation of the CCA would not be ethically justifiable based on the number of the physical visitors to the building. That is why online presence is inevitable and extremely important. An institution like the CCA, which focuses on research, cannot think of attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors without altering its genetic code: as Clint Eastwood said, “you have to know your limitations”.

The archive seems to be a pretext for you to spark off a new debate on modernity. You make almost an operational use of it. Is this correct?

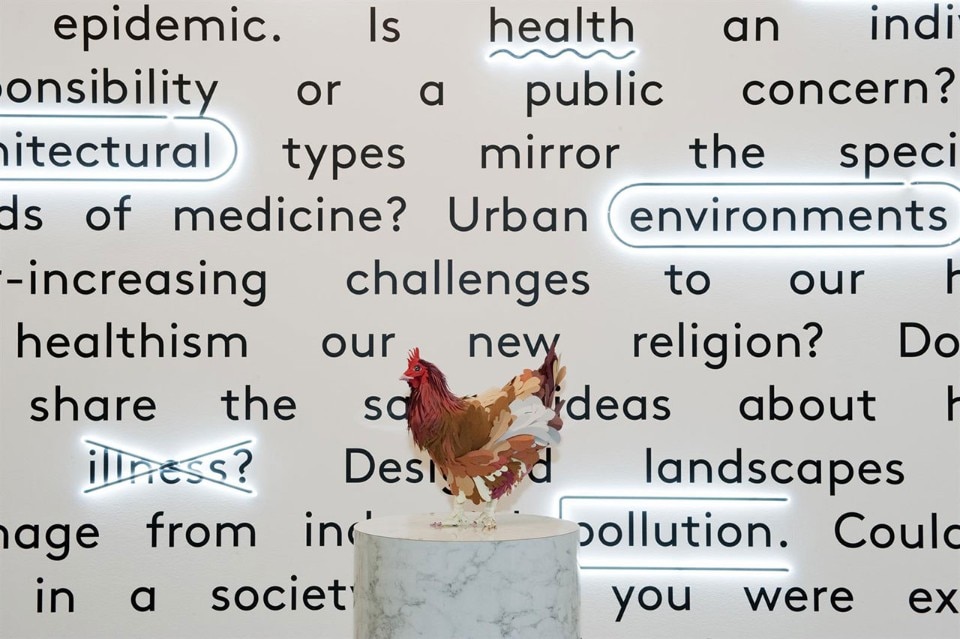

The CCA’s collection, exhibitions, publications, online presence and research are not strictly objectives, but tools for sparking off a debate. In recent years we have received many archives, like those of Jeanneret, Alvaro Siza and Umberto Riva, the FOA and Abalos-Herreros, Kenneth Frampton and Bernard Tschumi, and many architects who have decided to share their work and efforts. We therefore developed research starting from these collections, but we also did a lot of research, exhibitions and publications on topics that particularly interested us, such as the way of living, the environment, health and technology – all topics that contributed to create many more different collections.

Why did you focus on these topics?

I was interested in defining problems rather than pretending to offer solutions. I believe that today it is necessary to rethink the questions we ask ourselves, as well as the ideas and tools we use. To solve these problems, we cannot use the same tools that helped to create them. In any case, I don’t believe that architecture ever offers “the solution” to any problem: architecture is part of the problem, the institutions themselves are part of the problem. This is inevitable, but it is also important to be willing to move in one direction rather than another.

Can you give me a concrete example of one of these “directions”?

Let’s take the exhibition “Imperfect Health: The Medicalization of Architecture”. The research on this topic, which is so relevant today, pointed out some assumptions that we found quite problematic. One example is the Active Design Guidelines developed by the Bloomberg administration in New York. In this case, they focused on the importance of physical activity in parks and buildings, preferring, for example, stairs over elevators. Of course, I am not against encouraging more physical activity, but insisting only on this choice turns health into an individual moral responsibility, while completely ignoring the socio-political and economic dimension of the problem. We decided to highlight these contradictions, suggesting that these public policies should be questioned. The need for much more structural public intervention in our cities in order to address the complexity of certain problems is becoming increasingly evident.

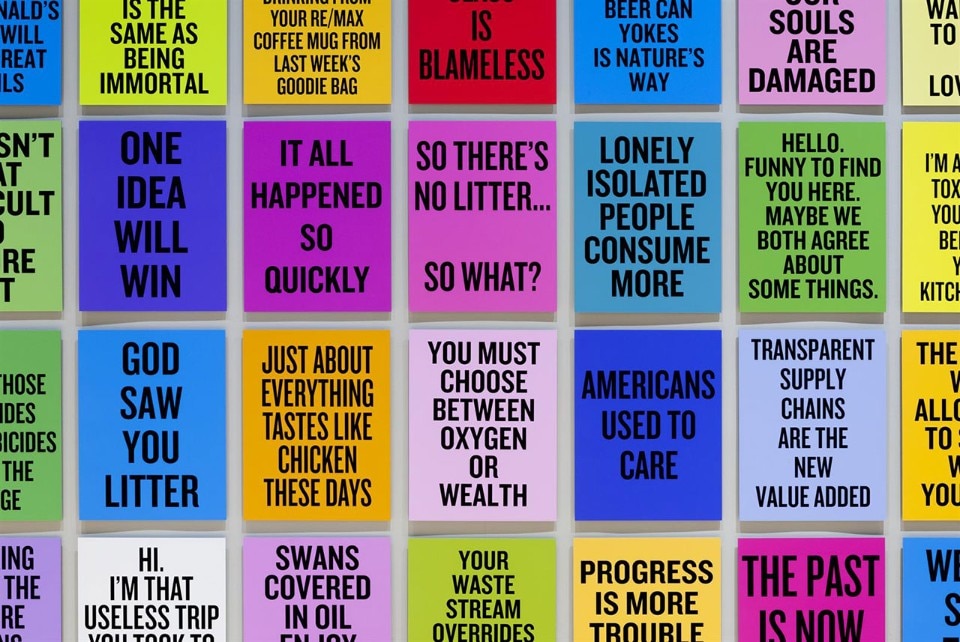

After 15 years spent directing the CCA, is there anything you haven’t changed your mind about?

I still think that neutrality in an institution is impractical. That every institution should have the courage to make its own voice heard. And that it should be ready to take responsibility. In 2016, for example, for the project and exhibition “It’s All Happening So Fast” we chose Canada as a case study to highlight the deeply hypocritical relationship that our society has with the environment today. Our critical attitude made us lose some economic support. However, we also unexpectedly aroused great interest from certain groups, politicians and the general public. I believe that independence and credibility are the most important requirements for an institution.

Opening image: The Museum Is Not Enough. This publication was conceived as the first volume of a yearly magazine, with which the CCA explores urgent questions defining its curatorial activity. Co-published in 2019 with Sternberg Press