In the 2020s more than ever before, Italy has become accustomed to the annual flipping of its popular cultural epicenters, all collapsing in the western Ligurian Riviera every end of winter. In Sanremo, in short. Five days of Festival della Canzone Italiana. One coastal city with very different souls – many in need of a refurbishment – one central temple, experienced more digitally than physically, but one. The Teatro Ariston. Which, by the way, was not even born for this purpose. Even more: it is not to be taken for granted, with the sets of the last decade having pushed their coils of ledwalls up to the gallery, and the orchestra sitting on the audience’s lap, that one can claim to know what is laying underneath; what the Ariston is, after all.

The Cinema Teatro Ariston is an expression of a modernist and figurative faith at the same time that comes from Italy in the midst of its postwar economy takeoff. What took shape in the second half of the 1950s on Via Matteotti – and would not become a festival stage until 1977 – was a project by Genoese professionals, Marco Lavarello, who focused on interior fittings, Dante Datta, Franco Ravera, Angelo Frisa for structures and Gino G. Sacerdote for acoustics.

View gallery

View gallery

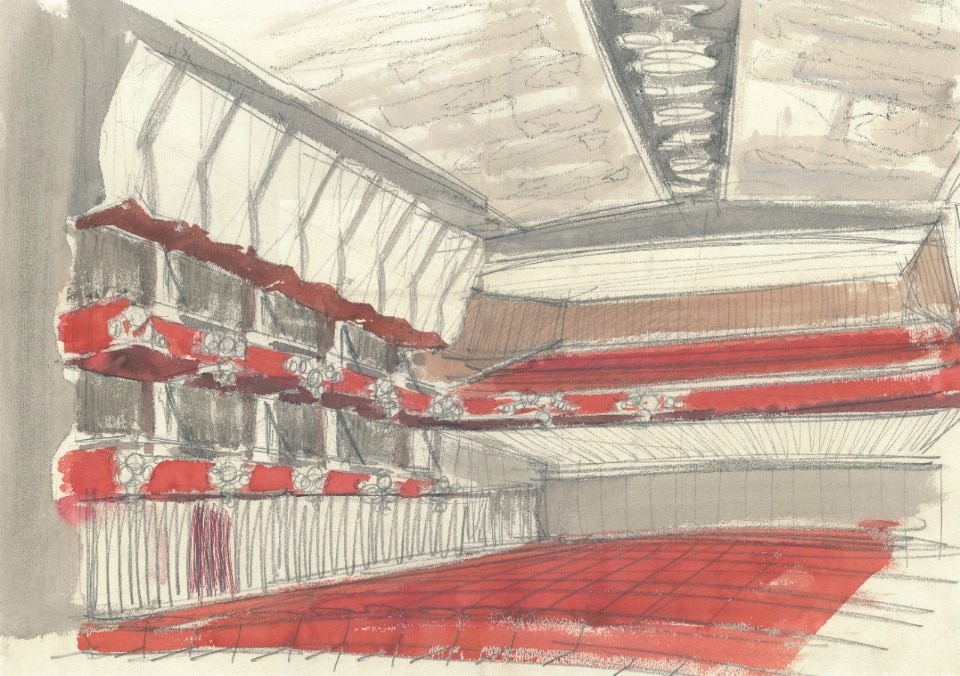

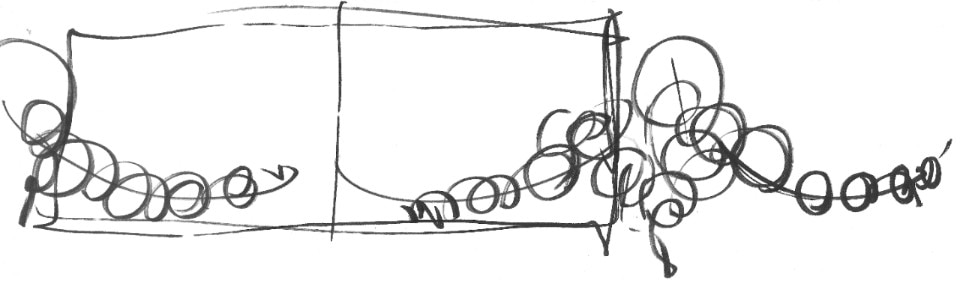

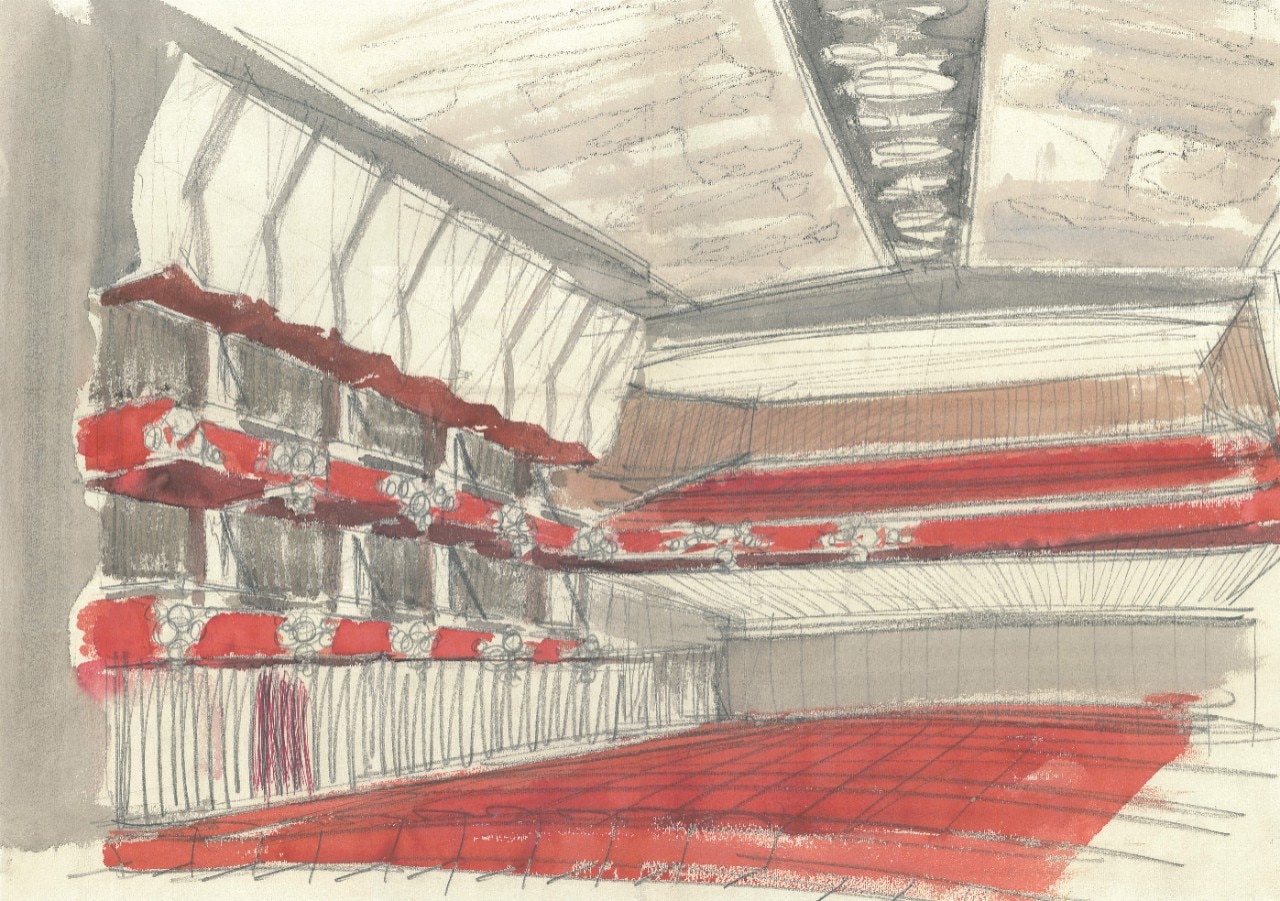

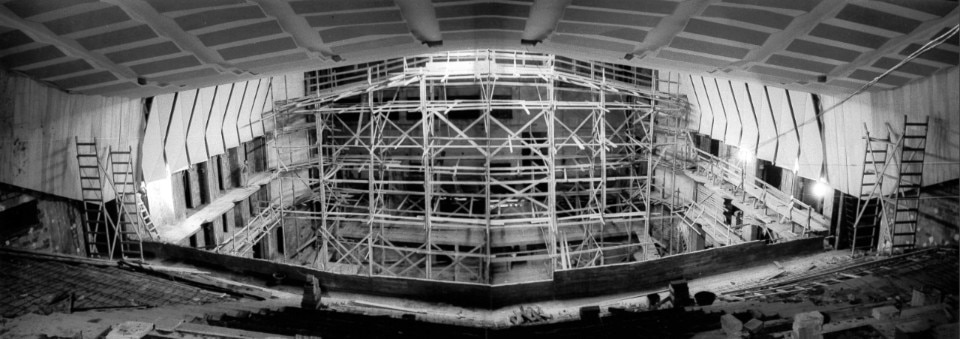

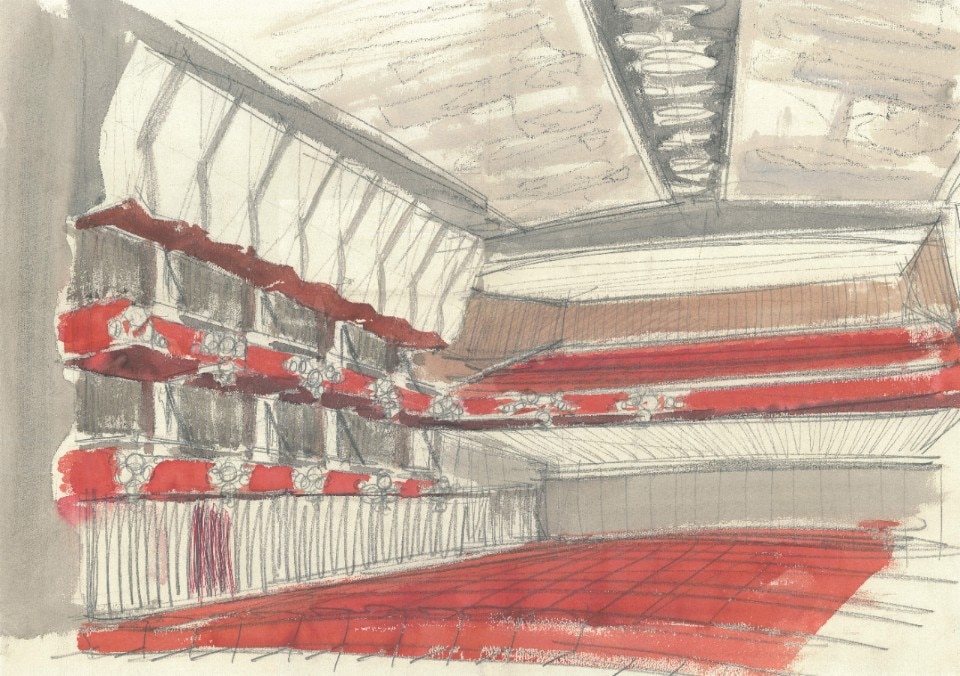

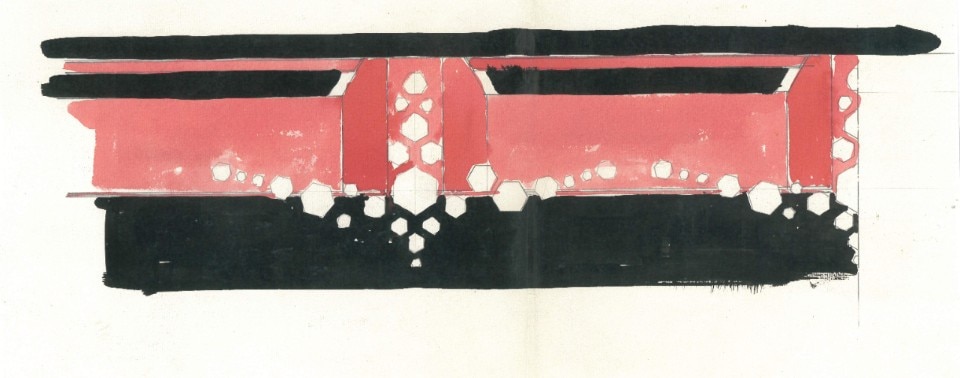

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

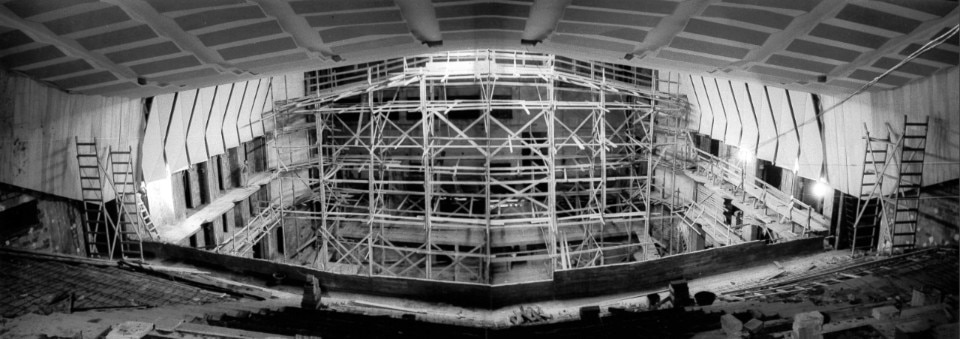

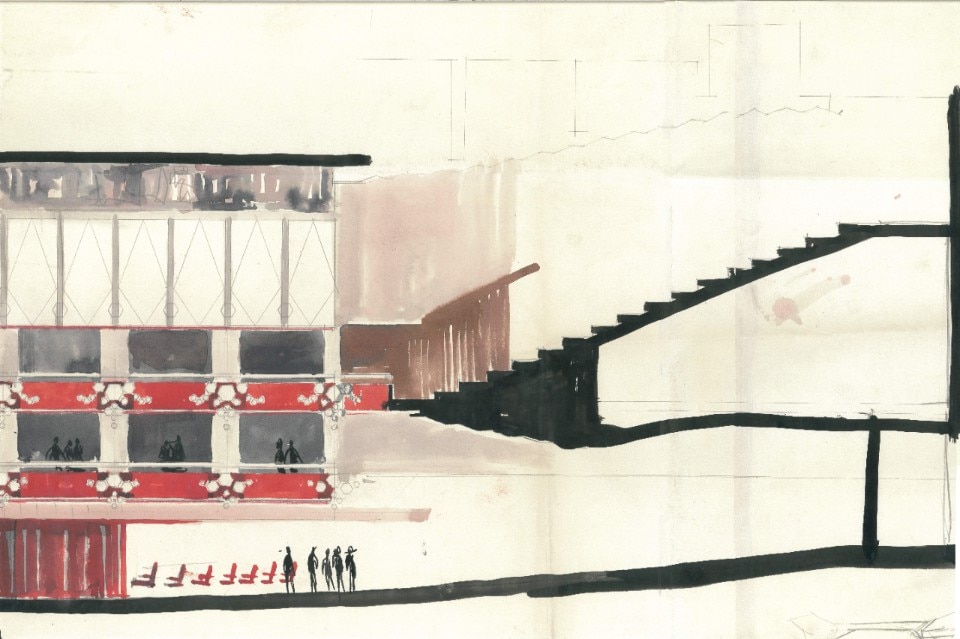

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

Ariston Theatre, Sanremo

Archival photos and sketches of the theater’s construction

Courtesy Antonio Lavarello

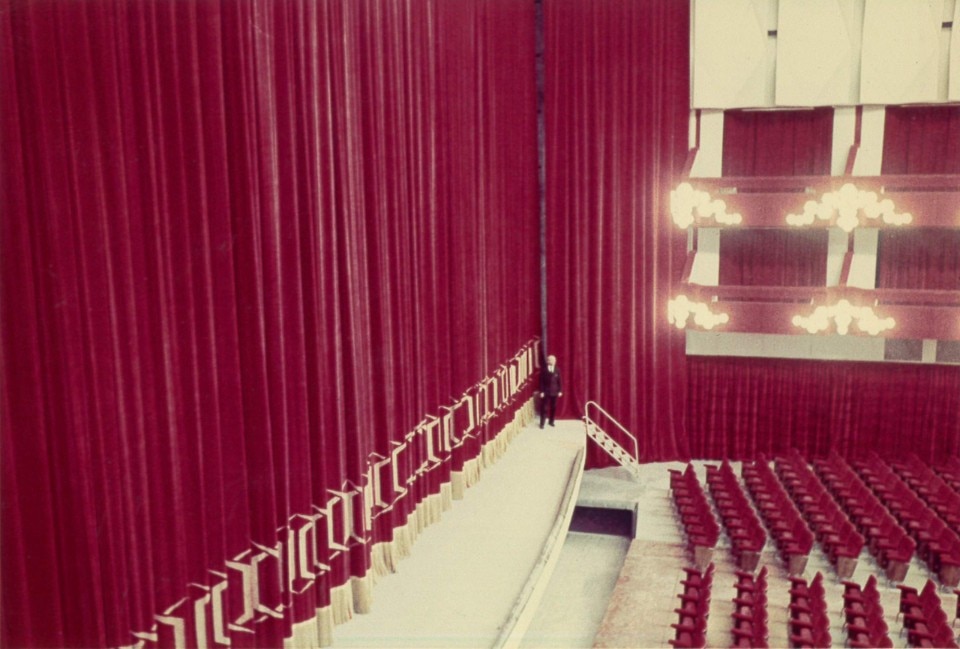

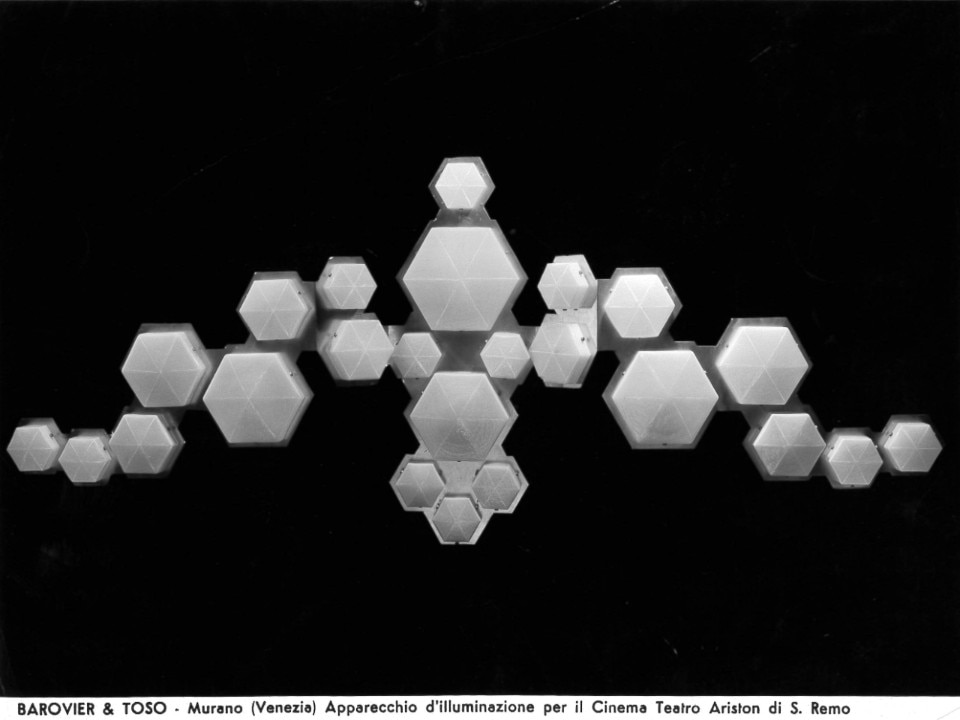

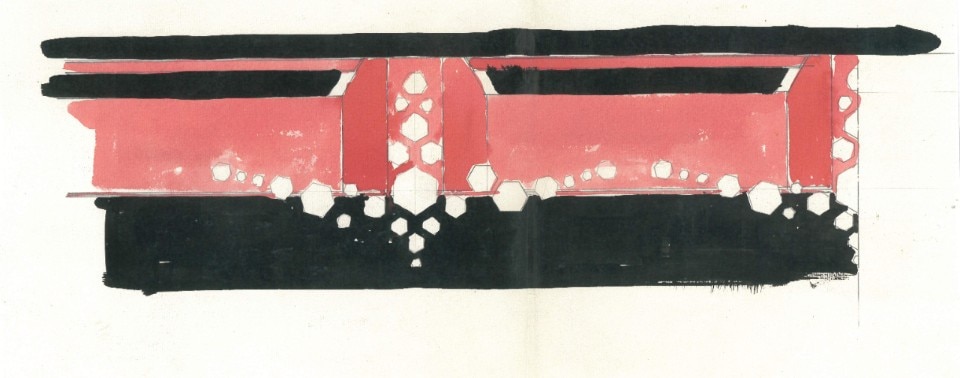

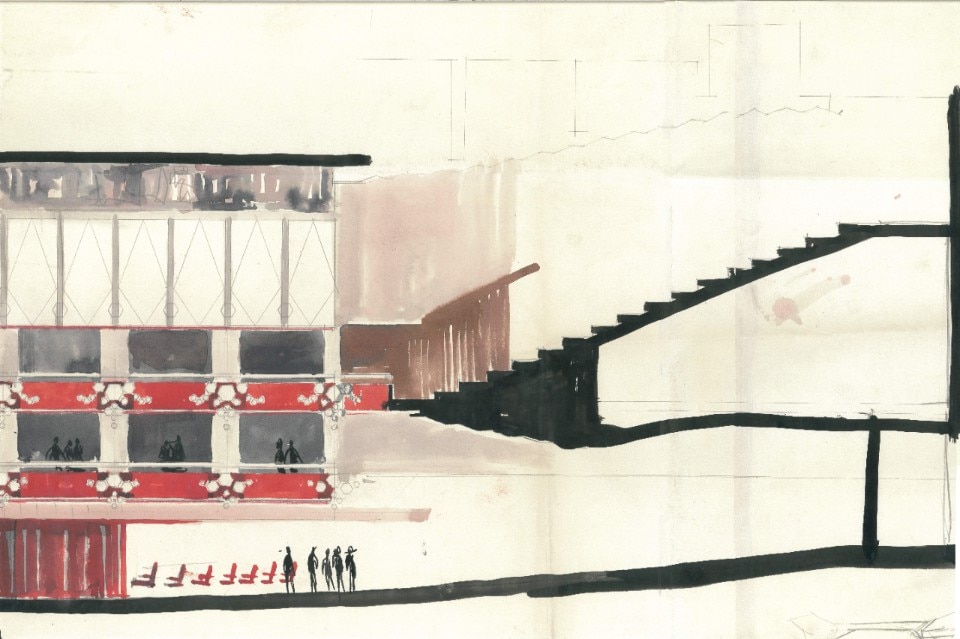

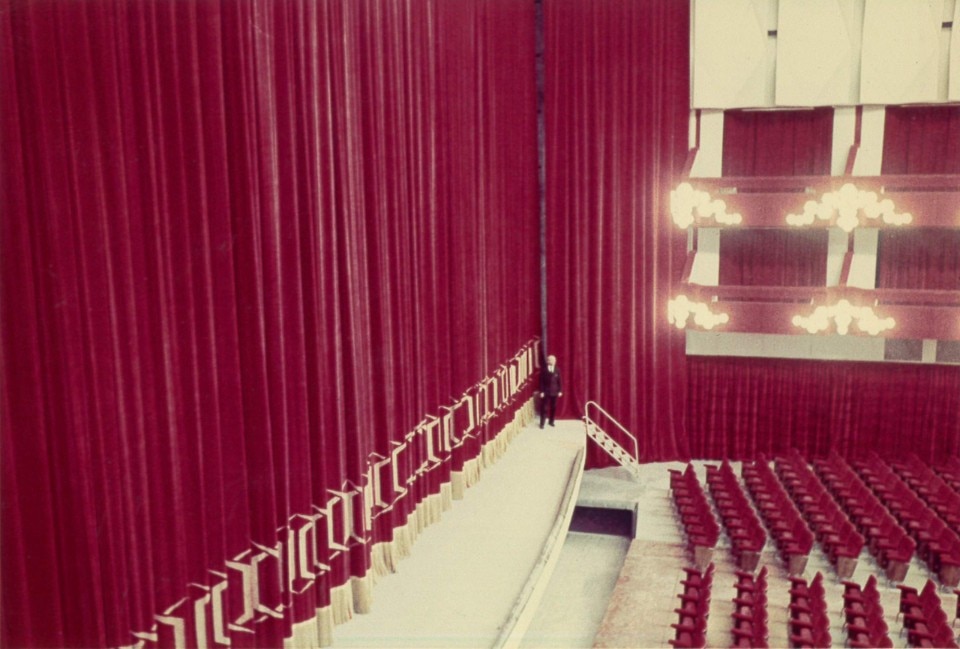

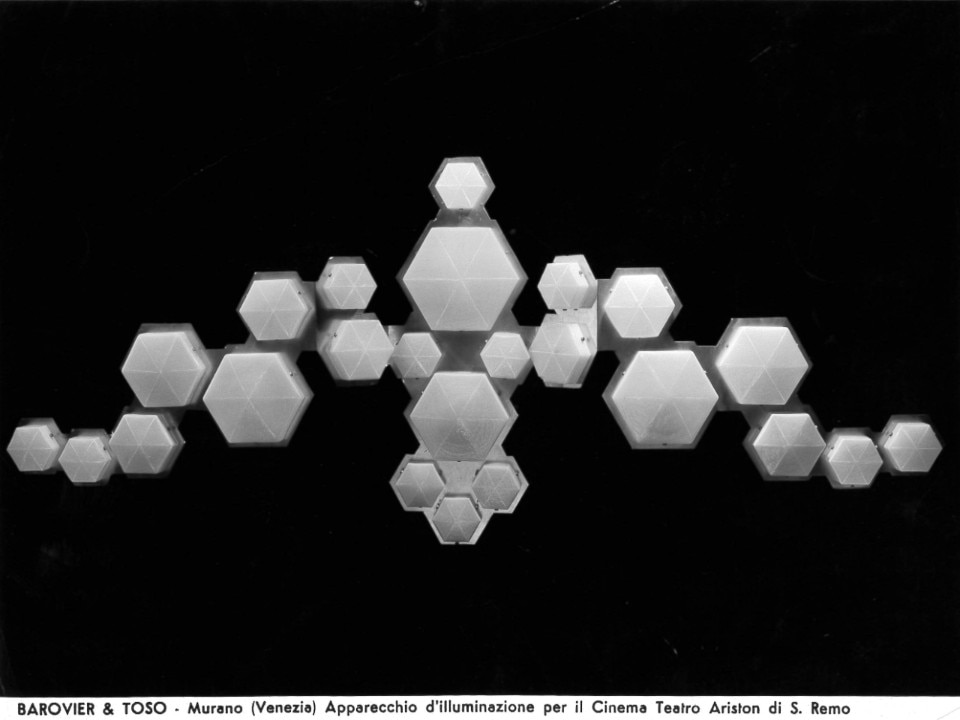

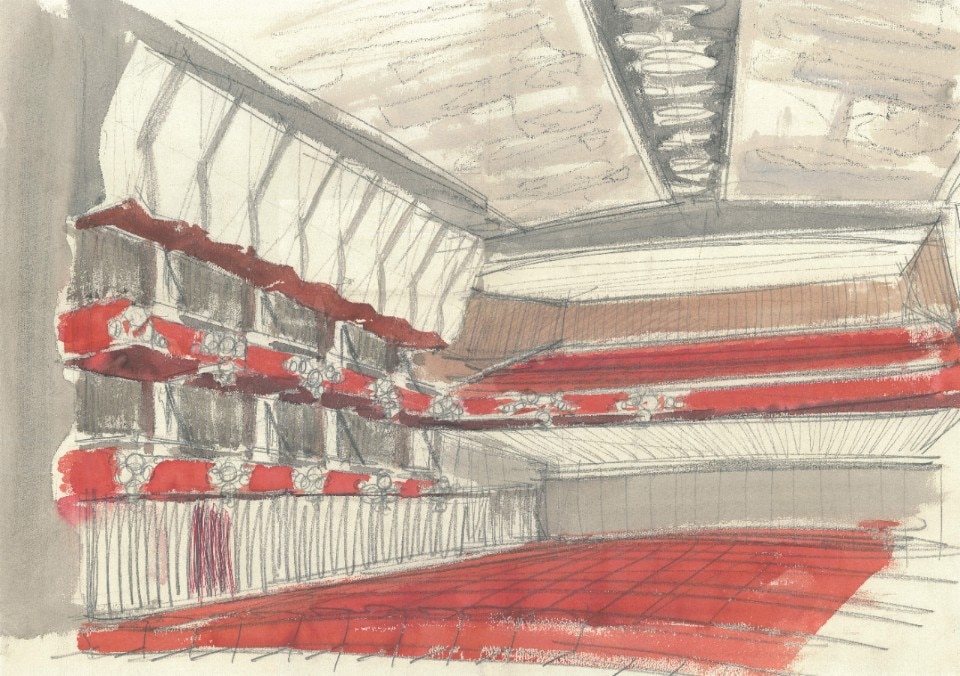

The main hall is strongly characterised: the fabric-like pleated ceiling, capable of playing with the lighting and at the same time contributing to acoustic comfort; the color red, a tradition of performance halls; and those patterned lighting fixtures, a constant landscape of live TV broadcasts from the 1970s to the 1990s, elegant geometric clusters of which, with the support of Antonio Lavarello, architect, researcher and curator of the Lavarello Studio Archive, we were able to reconstruct the whole gestation and birth, “from the first sketch of a ‘bungh’ of lights, to the geometric definition based on the hexagon, to the lights installed to pace the balconies via the prototype developed by Barovier and Toso of Murano” (i.e. the bursts of glass flowers interspersing the clusters).

In the foyer and staircase, floors designed in rhomboidal fields of polychrome marble recall Gio Ponti’s Villa Planchart or Via Dezza house in Milan, while on the pitched ceiling covering the hall was painted by Carlo Cuneo, with whom Marco Lavarello would embark on another way unconventional collaboration: the auditorium of the Leonardo Da Vinci liner.

These very two projects tell us a great deal about Lavarello and the Italy they gave a face to: the young Genoese designer, who had collaborated with Luigi Carlo Daneri and Dante Datta, with his studio opened in the late 1950s would work in interior design, temporary, graphics, and naval, nautical, and aeronautical outfitting. So many of his performance halls, immovable and otherwise, built independently or in collaboration: in addition to the Nuovo Margherita, Politeama Genovese, and Duse theaters in Genoa, the demountable one for the International Ballet Festival at the Nervi Parks, Lavarello also signed auditoriums for ocean liners, the aforementioned Leonardo Da Vinci (with Marinella Ottolenghi) and Michelangelo (with Mario Gottardi): the latter for some time would be the largest floating theater in the world. Automatic, though much more pop, to indulge in a comparison with the cruise ship that for some years has been in charge of splitting the magic device of the Ariston during the days of the Festival.