Monica Vitti, one of the most celebrated names of Italian and international cinema from the Sixties to the Eighties, passed away yesterday, in Rome, at the age of 90.

Whether she interpreted magnetic and enigmatic roles, or raucous vernacular ones, the actress stood out for her one-of-a-kind wit and her sophisticated elegance. For this reason, Vitti succeeded in imposing herself as both a popular icon and a star of essai cinema.

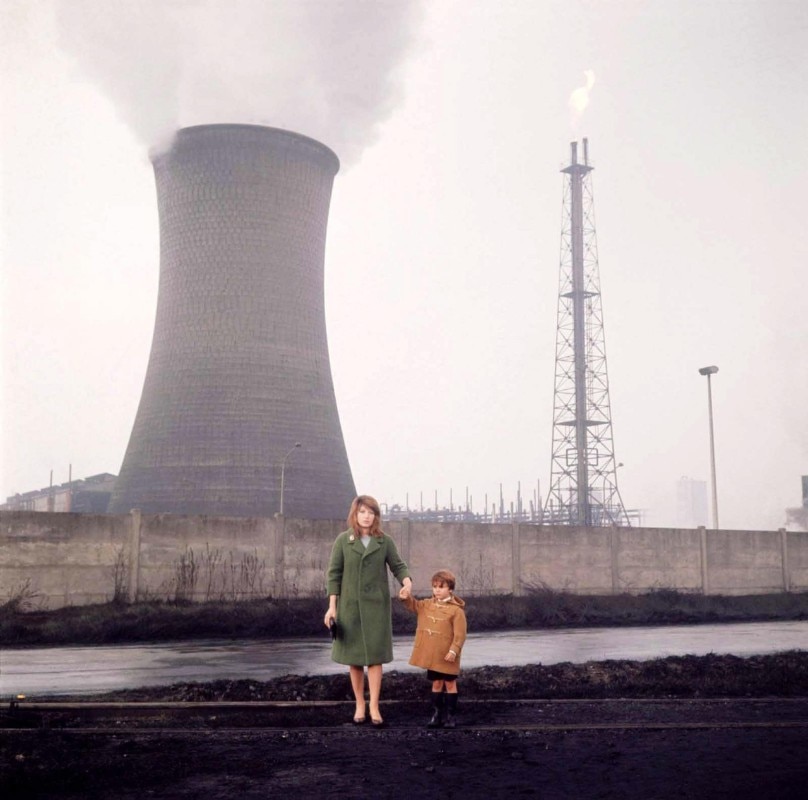

Such a charm was mirrored by the films she starred in, as if her presence only was enough to infuse them with grace and sophistication. Muse (both on set and in the private life) of Michealngelo Antonioni, Vitti became an integral part of the ethereal, existentialist and modernist iconography the director gave life to in the Sixties. In films likes L’Avventura (1960), La Notte (1961), L’Eclisse (1962) and Deserto Rosso (1965), Italian post-war architecture, its relationship with both rural and urban spaces, but also the mid-century interiors, all become cardinal elements in the narration of the alienation of the society of the times. Vitti moves against this background, with her refined portamento balancing her and the society’s existential dramas, human but alien, herself part of the new rising city.

Think of the role played in La Notte by the imponent glass surfaces defining the interiors of the clubhouse designed by Luigi Vietti for the Barlassina Golf Club in Lenate sul Seveso, outside of Milan, and theater of the chess game between Monica Vitti and the film’s protagonist, interpreted by Marcello Mastroianni. Not to forget, the desolation of the industrial landscape of Ravenna in Deserto Rosso, the post-atomic and metaphysical nuances given to the buildings of the Eur district, Rome, in L’Eclisse. Or, again, the alienation portrayed by the milanese neighbourhood of Sesto San Giovanni, still at the beginning of its process of cementification, and the neat geometries traced by milanese flats and skyscrapers (like Torre Galfa) in the silence of the summer in La Notte. It was no surprise, in fact, to come across such frames at the recent exhibition of designer Raissa Pardini at Poko Gallery in London. The film’s rhythmic game of shades and modernist surfaces composed part of the moodboard used to investigate the artist’s references and creative process.

In this context, the face of Monica Vitti, as much as her sober but immaculate clothes, her kitten heel shoes and penny loafers, became an integral part of the imagery of post-war Italy, contributing to defining it just like the clean and nervous jazz of Giorgio Gaslini, or the energetic twists of Giovanni Fusco from the CAM Sugar catalogue.

An exuberant star performer on stage, but a timid and romantic person in her private life, Monica Vitti once said: “I played at being someone else in movies and live theatre, and at being myself in life’s most intense, fascinating game – the game of love”.

The home therefore became the place where to express her intimacy, acquiring a prominence in the actress’ relationship with Antonioni. La Cupola, their house in Costa Paradiso designed in 1969 by Dante Bini by employing his Bini Shell patent, brought together the wilderness of rural Sardinia with the research for new and avant-garde forms of expression. But it also established a contrasting connection between the quasi-lunar landscape that had played such a big inspiration for Deserto Rosso and the architecture’s harmonious, semi-spherical concrete surface.

With her transition to comedy, and her artistic sodalitium with actor Alberto Sordi and acclaimed directors like Ettore Scola, Dino Risi and Mario Monicelli, the house becomes an opportunity for subtle and witty social commentary on the new Italian bourgeoise.

In Help Me, My Love (1969) husband Alberto Sordi thinks that by buying a new designer villa on the Sabaudia coast will help him solve the issues afflicting his delusional wedding with Vitti. In Jealousy, Italian Style (1970) Donatella, a working-class woman, promised in spouse to an enriched and social climbing butcher, reveals all of her and the partner’s lack of taste when contemplating his radical design house, the Casa Papanice by Paolo Portoghesi and Vittorio Gigliotti. “What are these canes?”, she questions, puzzled by the tubular decorations covering the house front. “A precise project of geometrical qualification. It was written on the house project,” replies just as perplexed the butcher.

The building – which now hosts the Giordania embassy in Rome – surely captured the attention of many directors, alo making an appearance in the Italian Giallo The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1971) by Sergio Martino.

In The Pacifist (1971) – a peculiar political drama by Hungarian director Mikos Jancso – living surrounded by sophisticated and artsy designer interiors becomes a shelter to the insecurities of journalist Barbara, torn between her social role of emancipated woman and her need for sentimental care.

The house, though, is also the environment where to keep secrets and sins, like in the brilliant comedy Io So Che Tu Sai Che Io So (1982) by and with Alberto Sordi, but also an environment to experiment with post-modern interiors. Take, for instance, the dialogue between plastic materials and the striking green-and-blue chromatic solutions of the flat of Amori Miei (1978) by Steno, where among the many pieces of design one can spot a bright green Brionvega Algol TV set.

Plastic, the queen material of the new Boom design, dominates the Pop-style furnishings of the home of the newlyweds Vitti and Albertazzi in the comedy Ti Ho Sposato per Allegria (1967) by Salce, based on a play by Natalia Ginzburg. A circular bed with orange vinyl sheets and balloons drawn on the walls in place of words, then, give an air of performance to a dizzy everyday life, daughter of comics and the frenzy of the consumer society.

PVC also returns in Monica Vitti’s costumes, in years in which the actress frees herself from the enigmatic roles of Antonioni’s films, becoming an icon of sensuality as well. There is the sapphic leather biker suit for Blonde in Black Leather (1975), a road movie with a feminist flavor together with Claudia Cardinale, and the outfits with which the crazed Sicilian hitman, wounded in honour, Assunta Patanè becomes a yè-yè femme fatale. With her mini skirts, wigs, black PVC coats and orange nylon jackets Vitti played one of her most significant roles in The Girl with the Gun (1968) – which also features the Royal Crescent in Bath, one of the most distinctive examples of English Georgian architecture.

Vitti, therefore, was also a pop icon to the point of embodying one of his heroines, Modesty Blaise, in a 1966 film directed by Joseph Losey. The movie is a concentrate of costumes that move between Sci-Fi and Space-Age, optical sets and instruments that become design objects, a bit Barbarella a bit Diabolik in Swinging London sauce. This experience will lead her to pose for photographer Terry O’Neil, but also to inspire directors and artists. Like the painter Jaroslav Vožniak who will dedicate her a portrait in 1969.

“I have always been deeply moved in front of a painting, like a story, like a confession, like falling in love. The colours, the lines, make my heart beat and take me away from everyday life,” once stated Monica Vitti.

Not surprisingly, one of the most candid images of the many that portray the actress is the one in the company of Antonioni, absorbed in contemplating Giacometti’s sculptures at the 1962 Venice Biennale.

Opening image: Monica Vitti in the industrial area of Ravenna on the set of Deserto Rosso (1965) by Michelangelo Antonioni. Photo film frame

Marble matters– exploring Carrara’s legacy

Sixteen young international architects took part in two intensive training days in Carrara, organized by FUM Academy and YACademy, featuring visits to the marble quarries and a design workshop focused on the use of the material.