As architects living and working in the occupied territories of the West Bank, stone forms the bedrock of the historic urban fabric that surrounds them, informing their sense of place and identity as Palestinians.

But thanks to an archaic building regulation, a curious hangover from the Ottoman Empire, stone is more than a matter of heritage. It is also their single greatest material constraint.

“The ruling states that at least 70 per cent of the envelope of a building should be covered in stone,” explains Yousef Anastas, who is currently completing a PhD in advanced stone construction techniques.

View gallery

View gallery

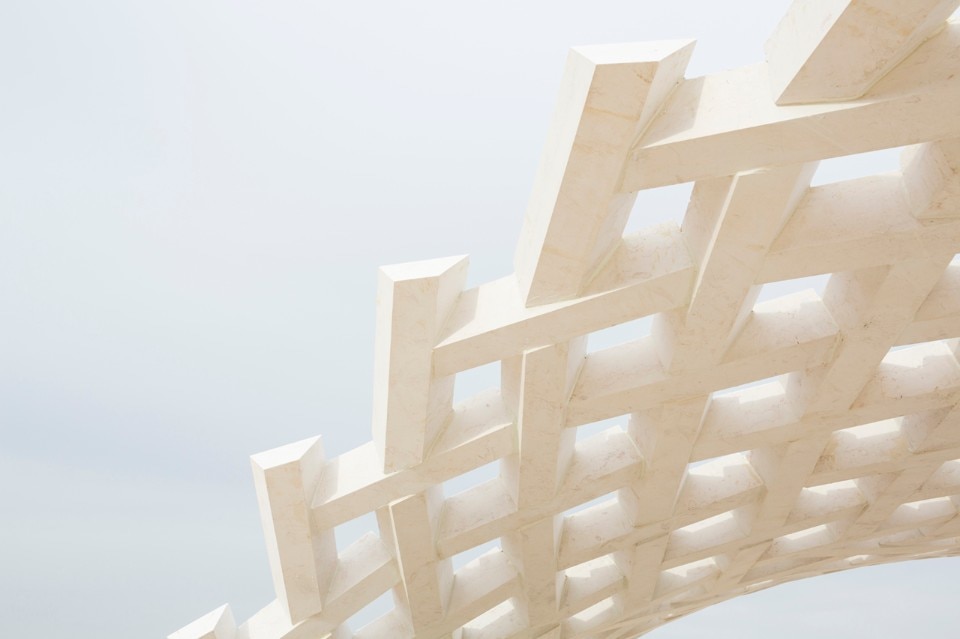

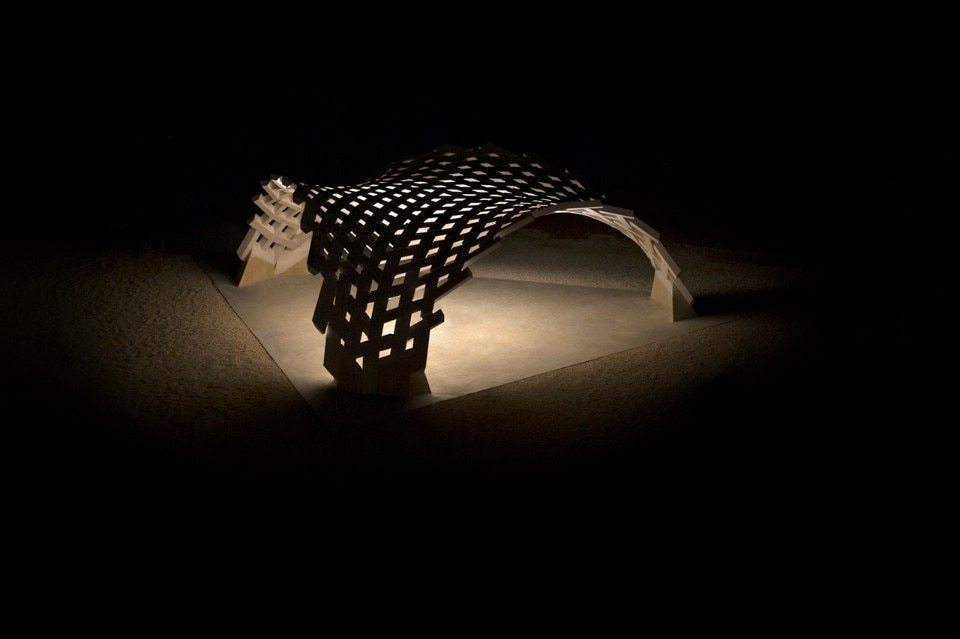

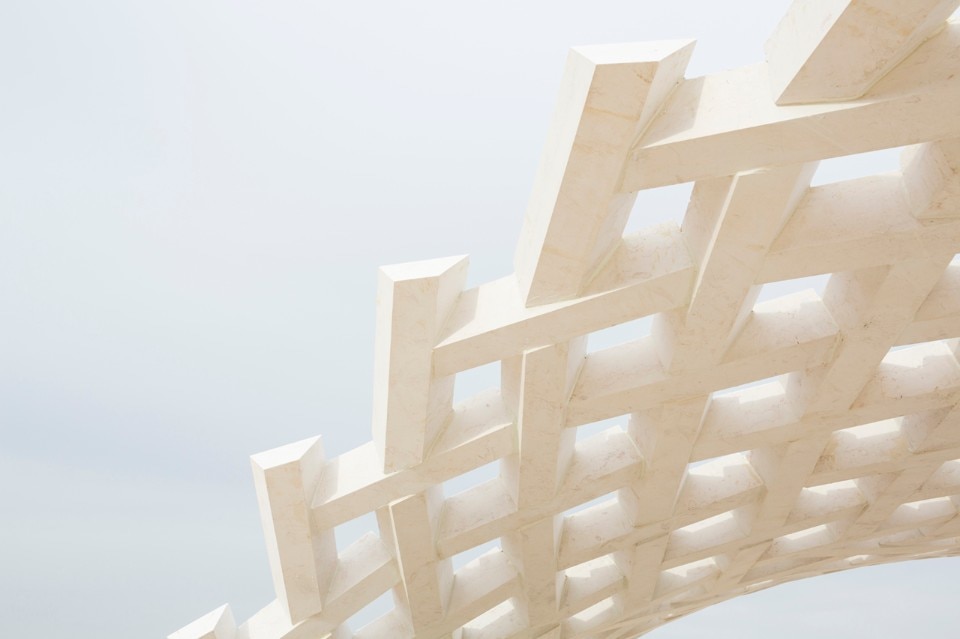

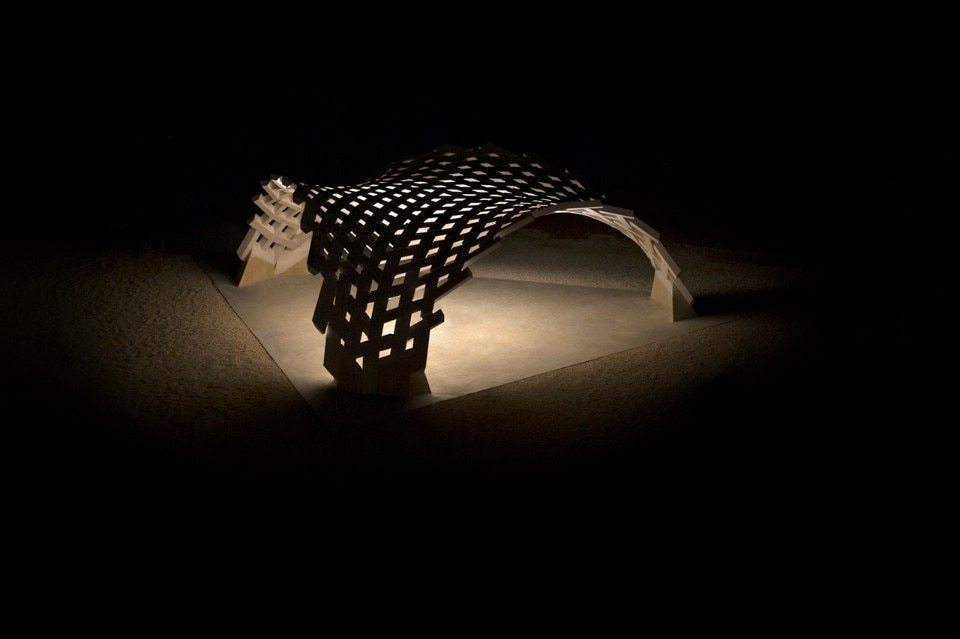

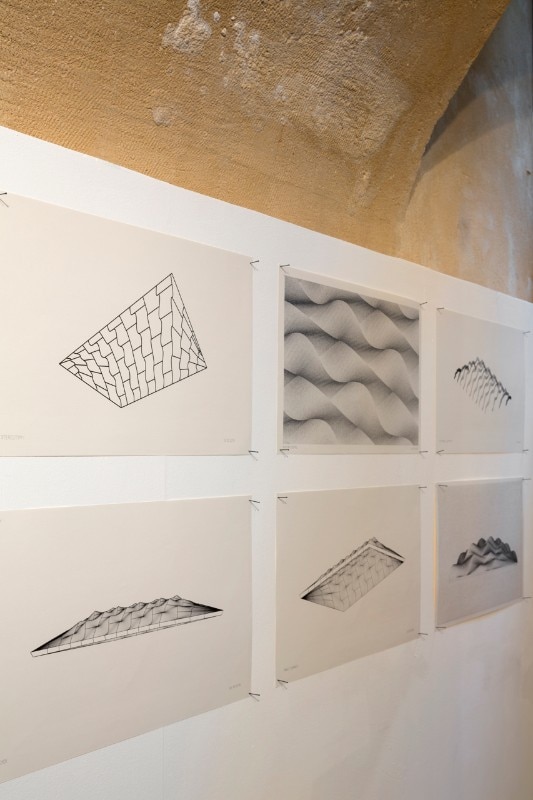

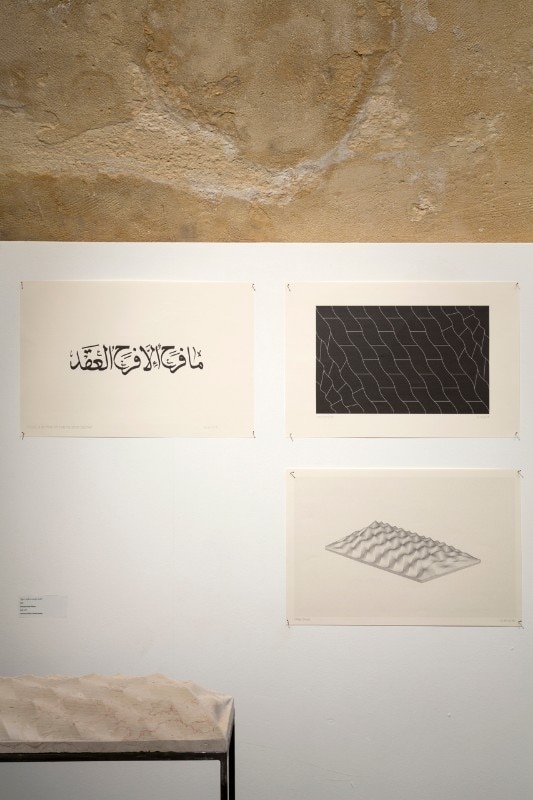

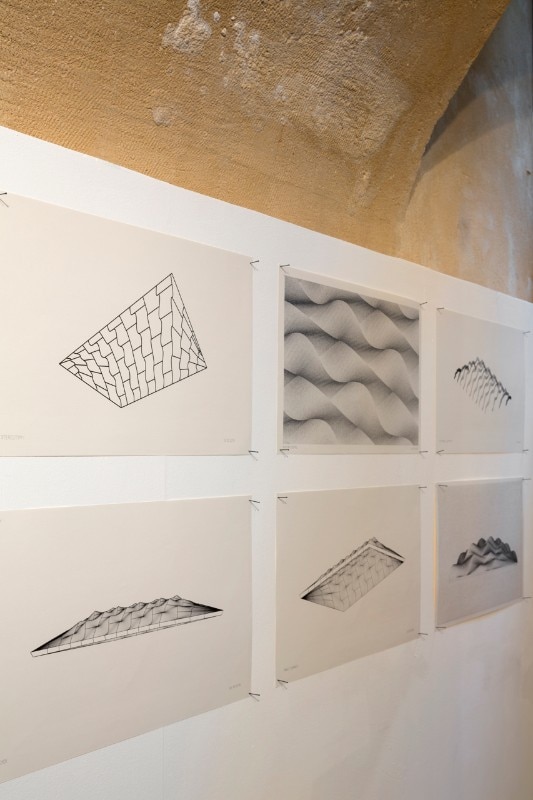

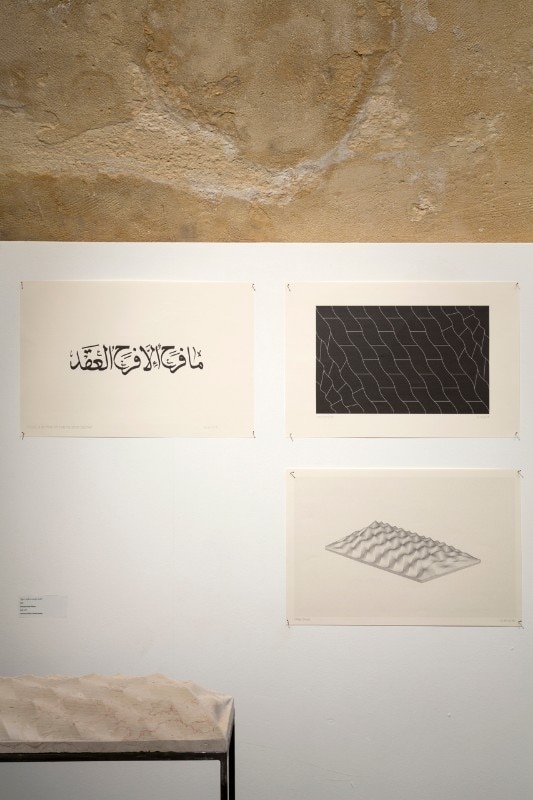

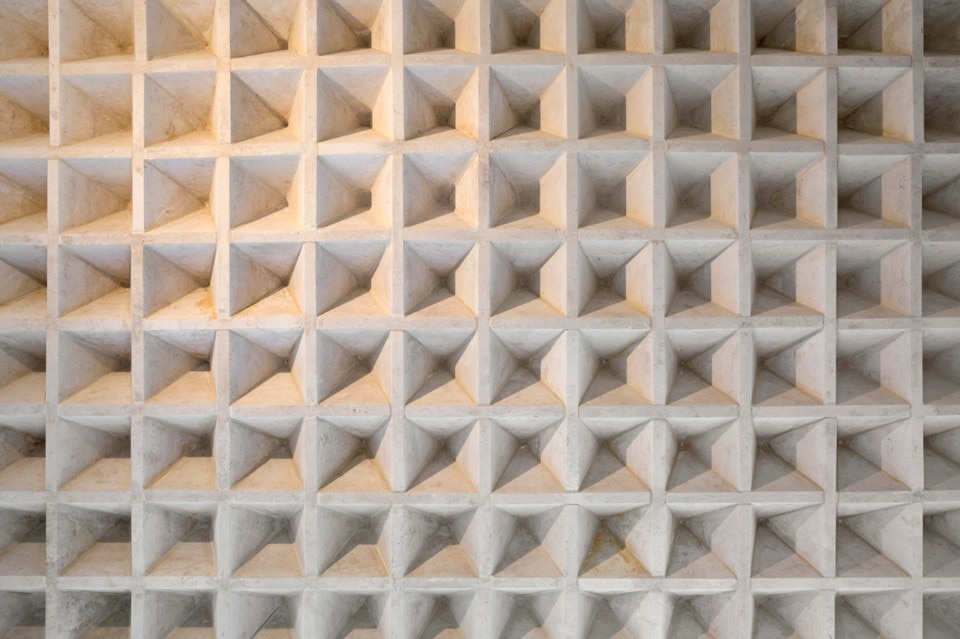

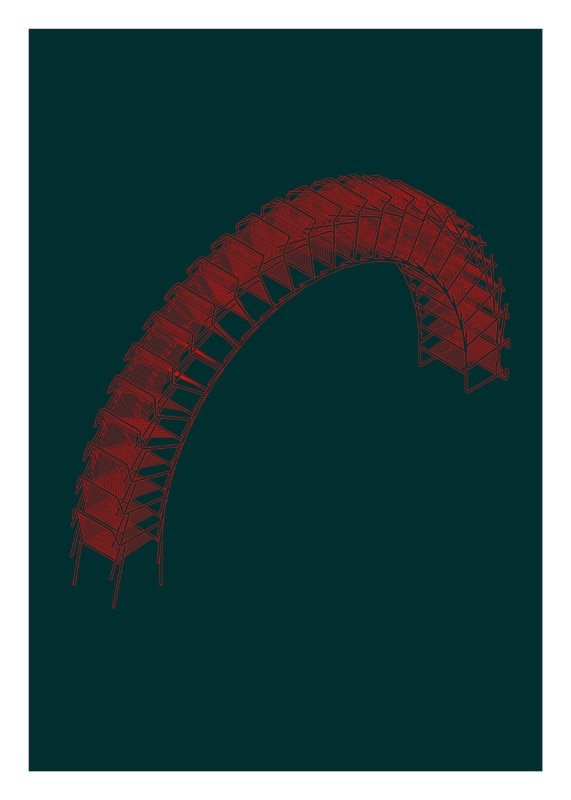

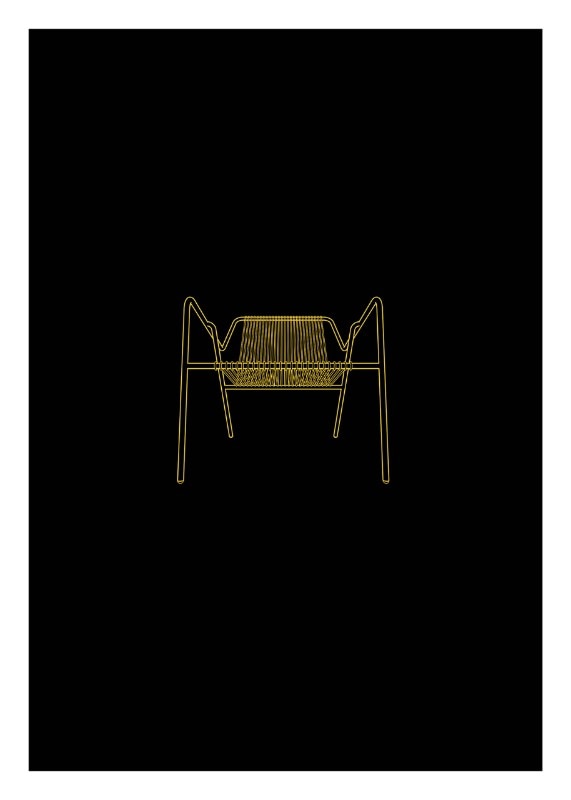

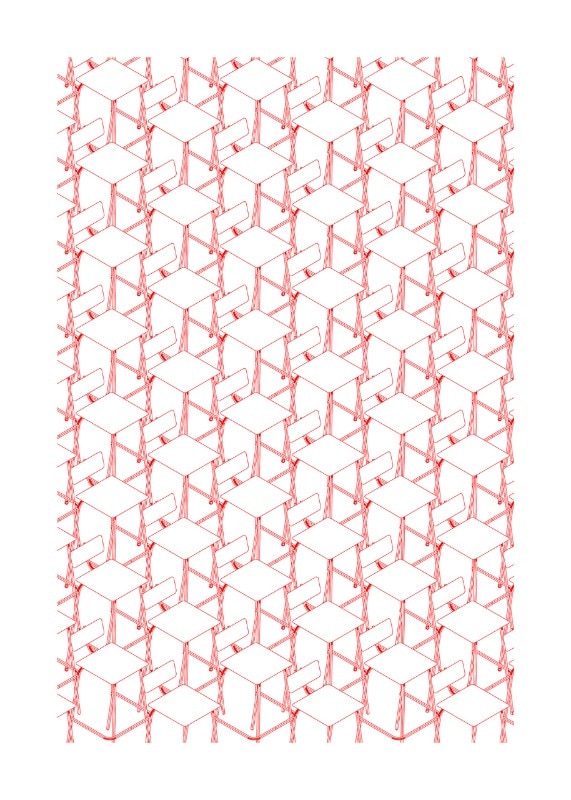

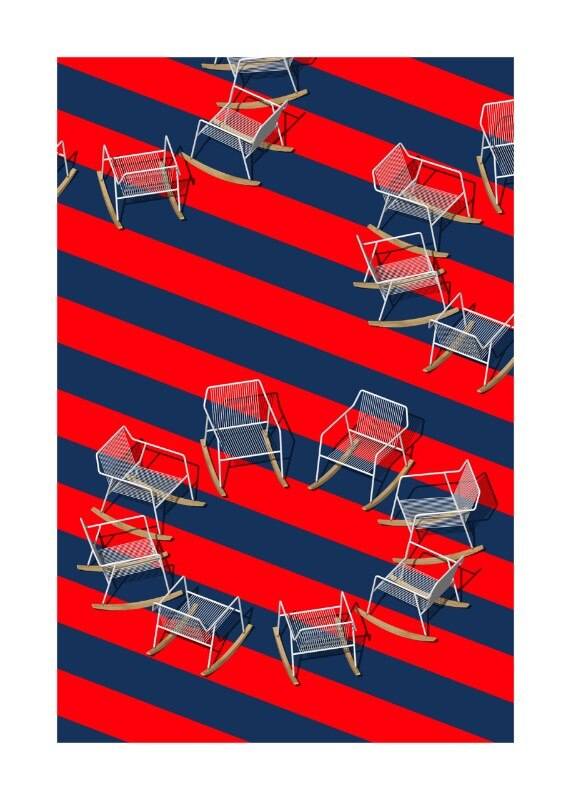

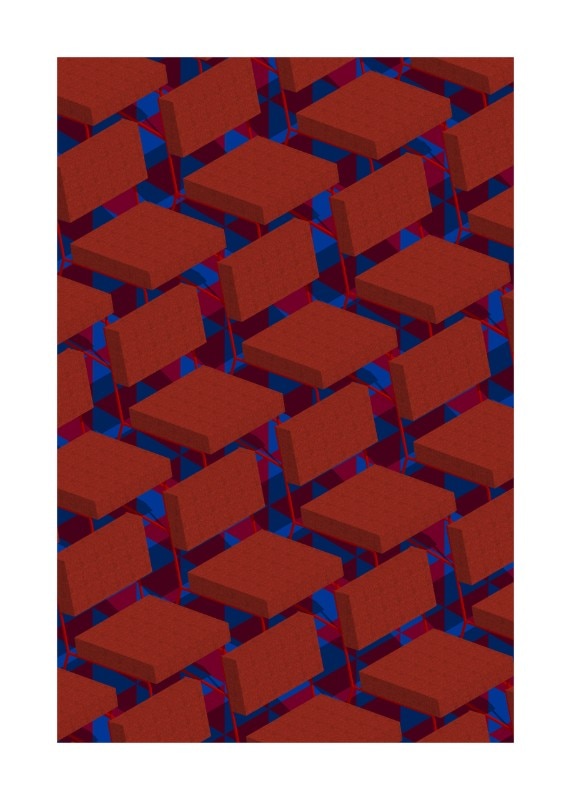

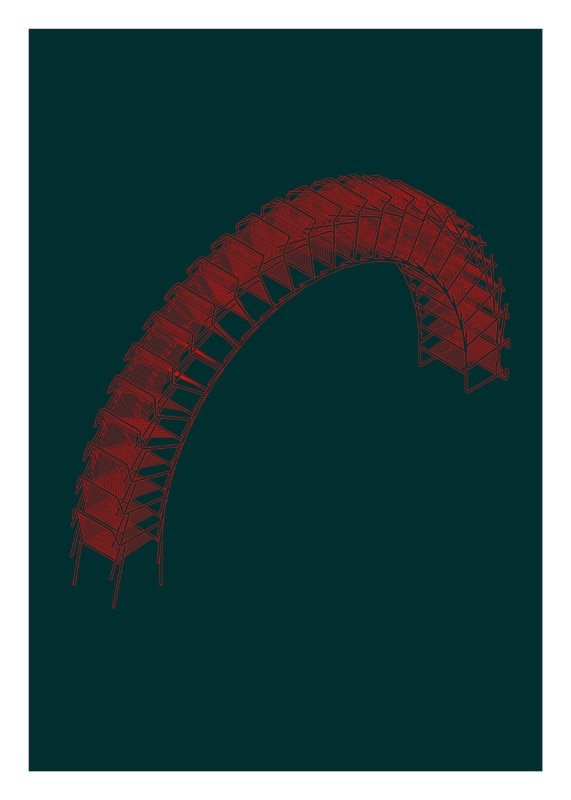

Stonematters

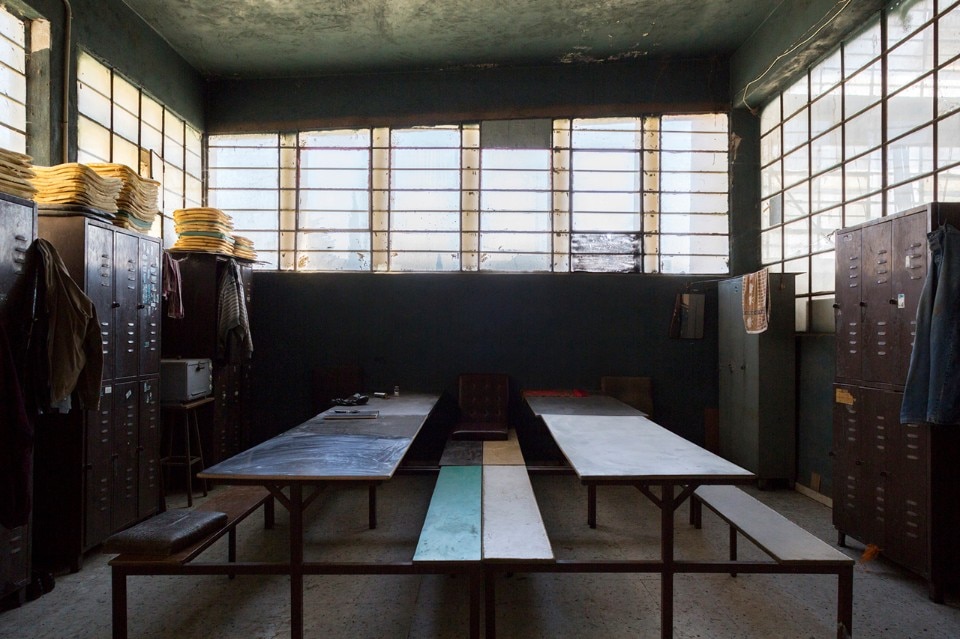

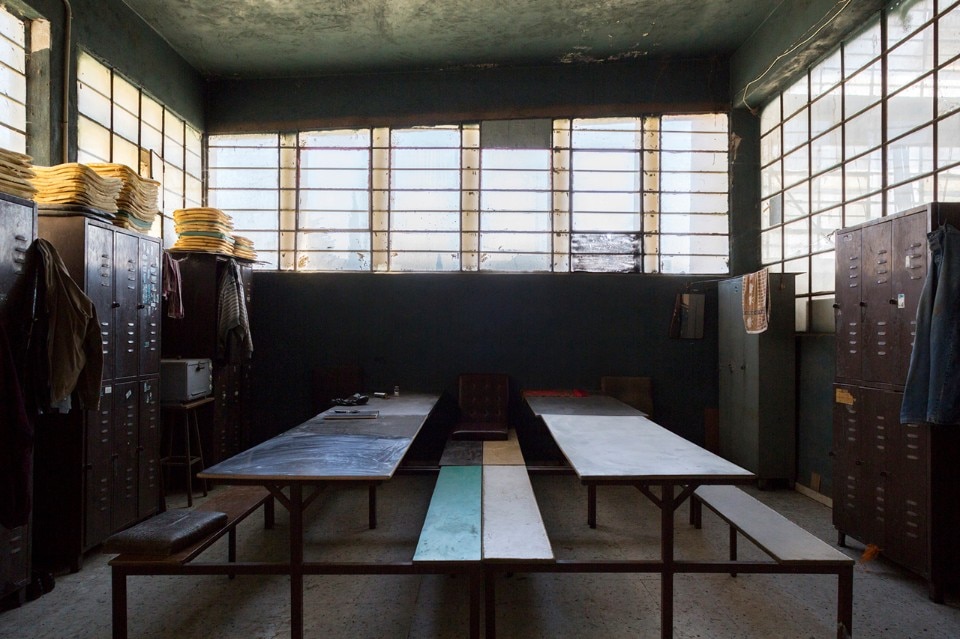

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

Stonematters

The research department of AAU ANASTAS "Scales" and the GSA Lab of ENSA Paris-Malaquais are examining the use of three-dimensional freeform stone in Palestine. The research aims to include stone stereotomy, stone cutting processes, construction processes in contemporary architecture. It is based on new computational and manufacturing simulation techniques to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language. The results of the research will be used to build the residence of artists and writers of el-Atlal in Jericho. As such, Stonematters is the first module of the residence and the first constructed vault of our research.

AAU ANASTAS, Stonematters, Jericho, 2017

“Traditionally it was used as a structural material, but now it is increasingly being used as cladding for concrete structures.” For the brothers, who are on a mission, they say, to “desacrilise” stone and to reintroduce it into contemporary architecture as a structural system, the current pattern of Palestinian urbanism is proof positive of their belief of intimate connection between the design of the smallest architectural elements and urban morphology.

“Because we are forced to use stone in an urban context, you end up with structures that are all the same size because the [stone] factories are all set up the same way and our research began as a reaction to this uniformity,” Yousef says. For Elias Anastas, their experiments are also a reaction to the rapidity in the development of the Palestinian city.

View gallery

View gallery

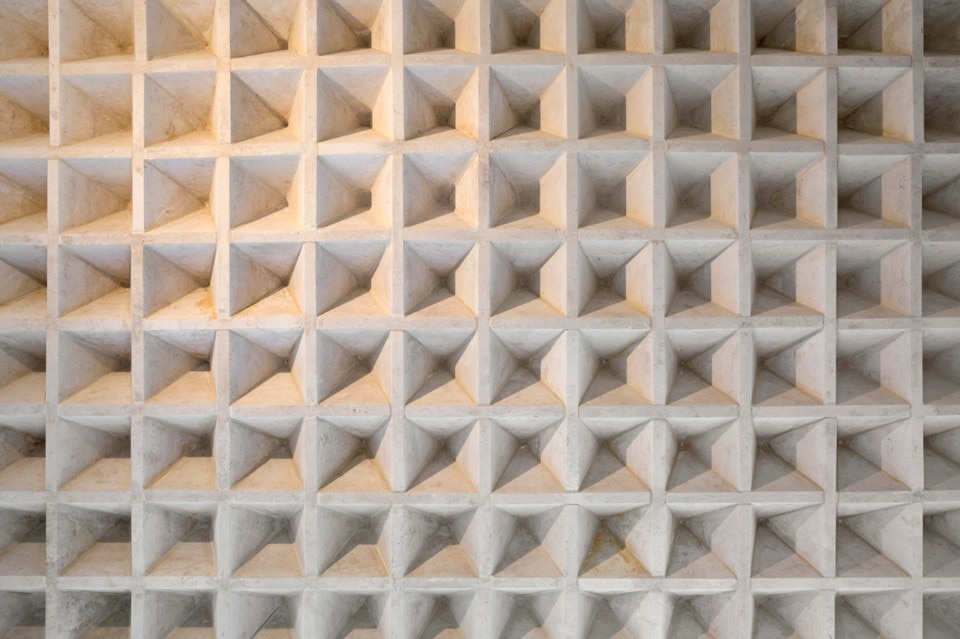

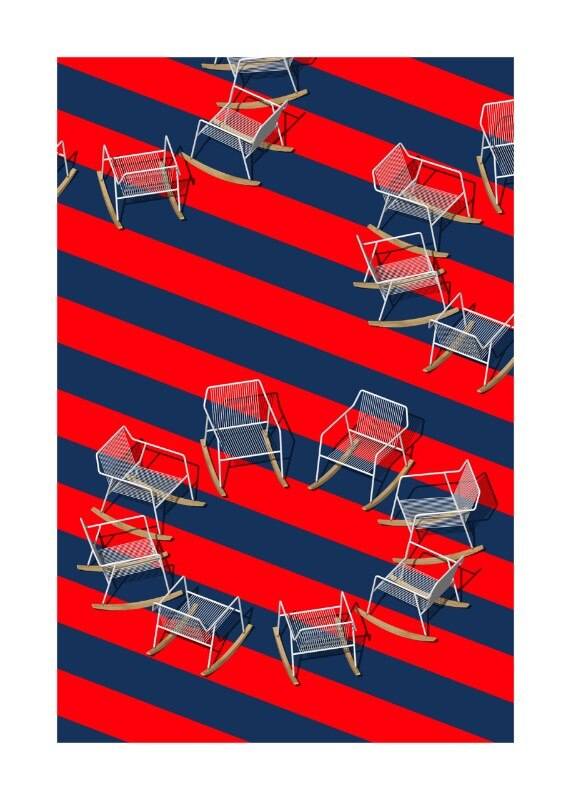

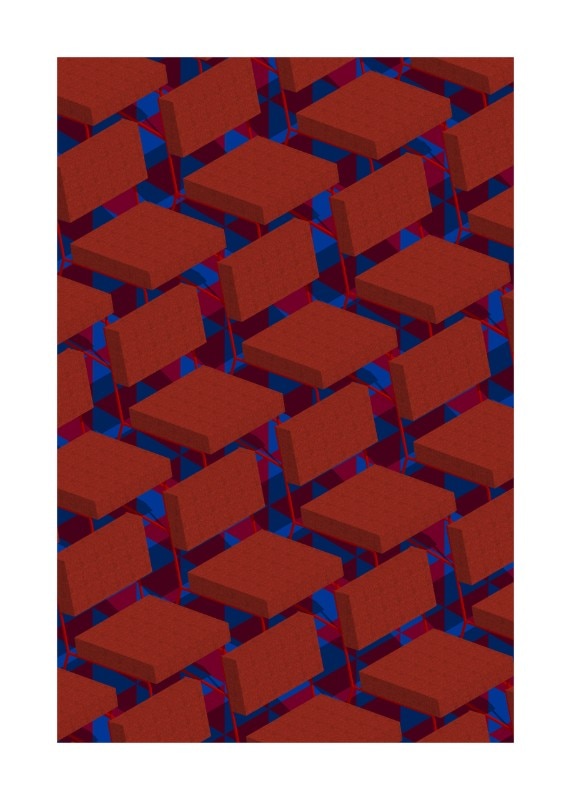

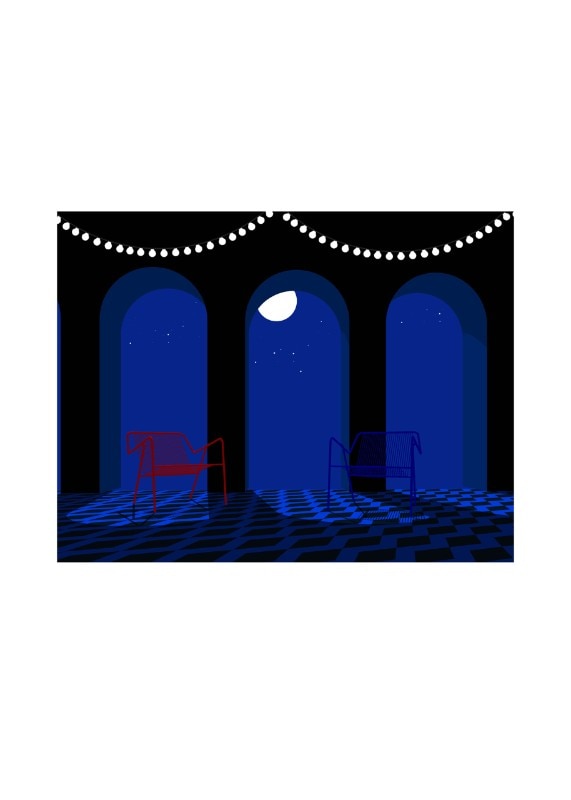

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

While We Wait

While We Wait is an immersive installation about the cultural claim over nature. The towering structure consists of small elements of stone from different regions of Palestine, fading upwards from earthy red to pale limestone. The stone elements are shaped by both revolutionary and traditional techniques: they are designed on a computer, cut by robots and hand-finished by local artisans.

AAU ANASTAS, While We Wait, 2017

“What’s happening at the moment isn’t linked to architecture, it’s automatically linked to the consumption of land because the moment you build, it protects the land in some way from being expropriated,” he explains. “So the question of how you build is no longer on the agenda. The question is how you do it as quickly as possible, but as architects we want to generate cities that are more adapted to ways of living.”

View gallery

View gallery

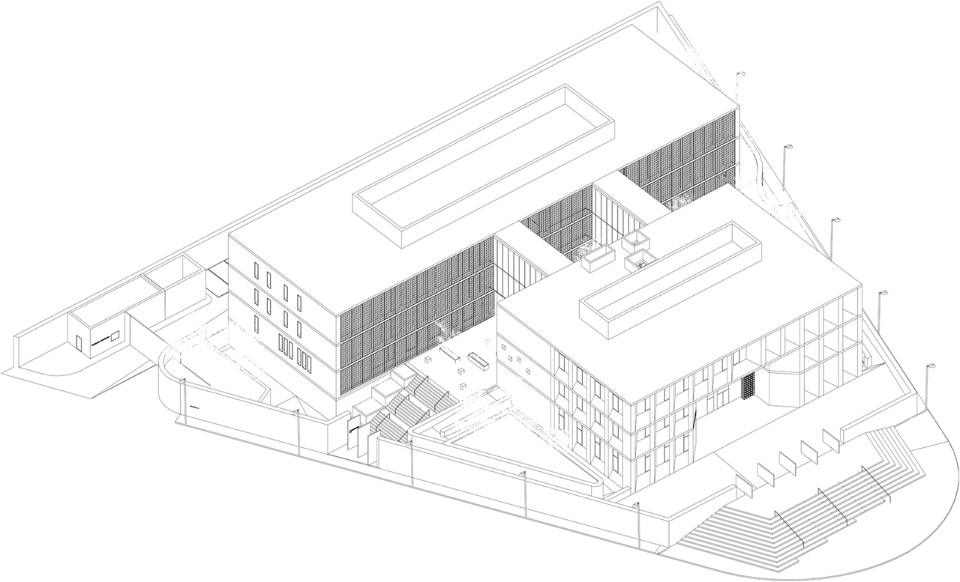

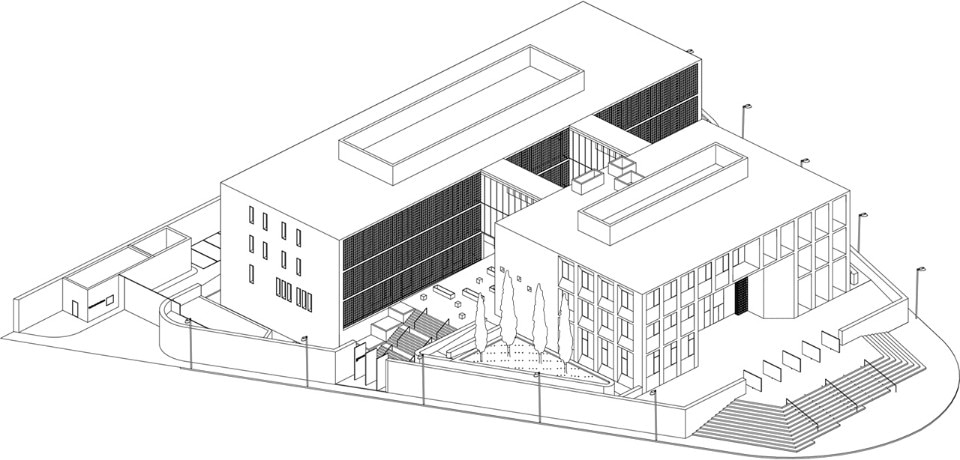

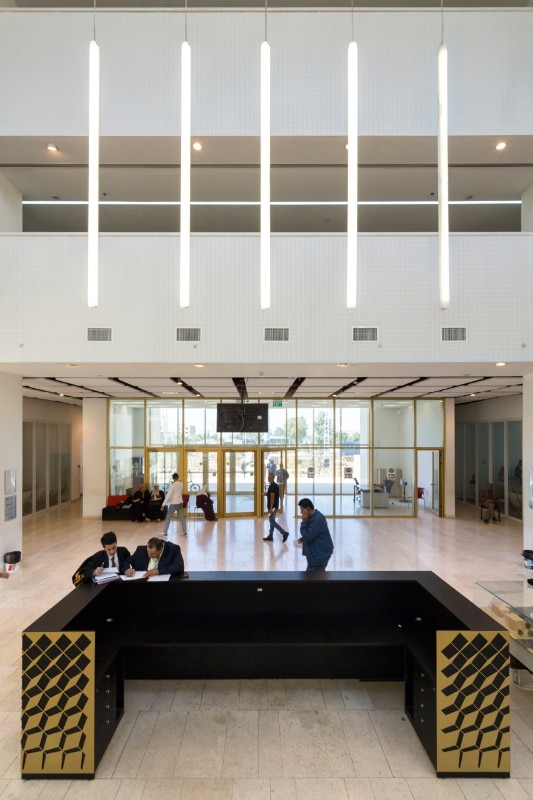

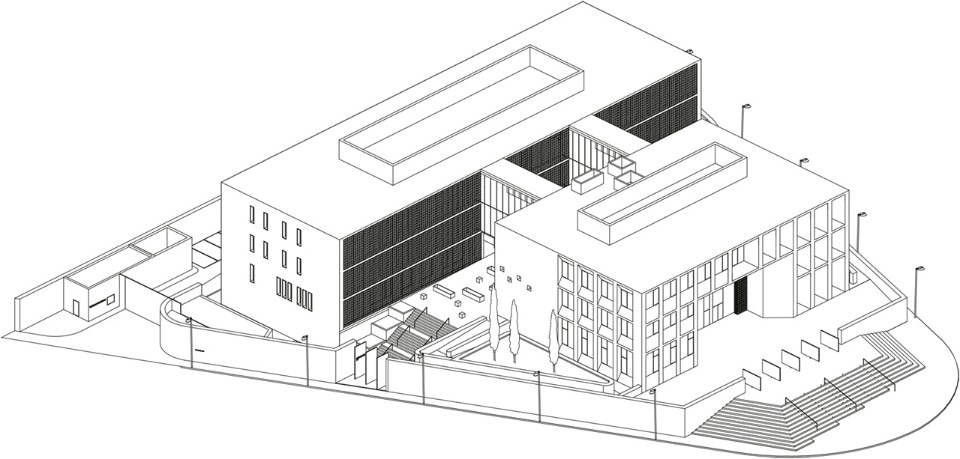

Toulkarem Courthouse