The relationship between cities and water has been central to urban discourse for several decades. Since the late 1970s, the wave of large-scale urban regeneration projects has often taken water — rivers, canals, ports, and waterfronts — as a starting point for reclaiming deindustrialized, polluted, or neglected territories. In many European and North American cities, the transformation of former port, industrial, or infrastructural zones has aimed to redefine entire districts through new public spaces, housing, parks, and accessible riverfronts.

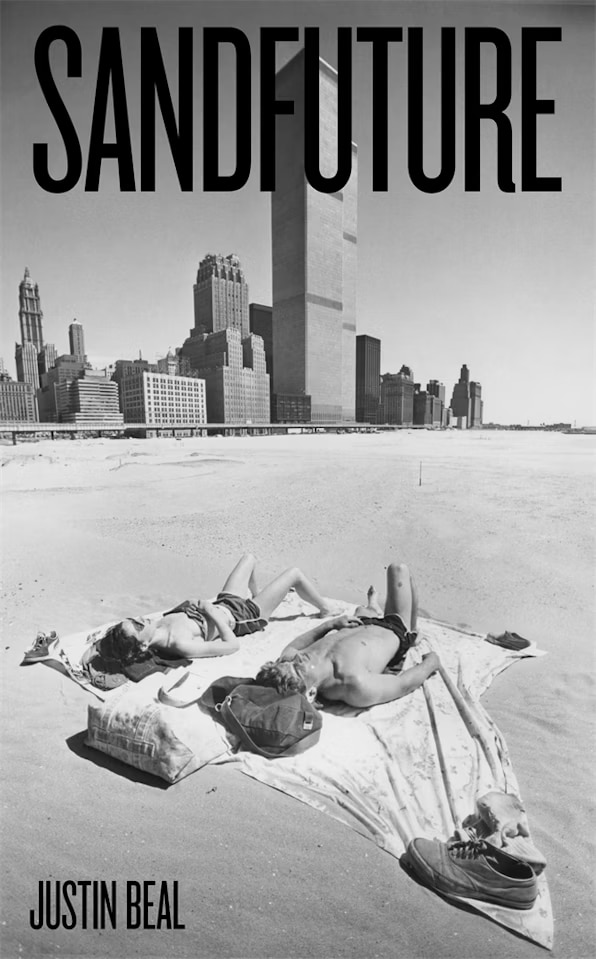

One example is Battery Park City in New York, developed from the 1980s on reclaimed land along the Hudson River, adjacent to the original World Trade Center site. Before the area was formally redeveloped, a temporary urban beach had emerged spontaneously on the site, used informally by residents for swimming and leisure during a pause in construction—an improvised and unplanned aquatic space in the heart of the city.

Today, in the context of climate crisis and increasingly intense urban heatwaves, the question of urban swimmability has returned with urgency. In many landlocked cities, new initiatives seek to reopen access to rivers, canals, and basins through ecological filtration, light infrastructures, and renewed forms of collective use of water. These projects combine environmental mitigation, climate adaptation, and redefinition of the public realm, reframing the everyday relationship between urban dwellers and water.