Over the course of his lengthy career, James Wines’ advocacy for quality surroundings has taken on many forms, including architectural design, industrial design and art. After having lived in Italy, he returned to the US and founded SITE (for "Sculpture In The Environment") in New York City in 1970, where he has been blurring the programmatic boundaries between these disciplines ever since.

SITE is at once a design office and an environmental art atelier, known for breaking the rules of modernism through an unconventional approach and being generally critical of contemporaneity. Technology, information and ecology in their post-industrial versions are the key focal points of SITE and its founder, who is linked to the Italian movement of Radical Design. Wines has synthesised his concepts in buildings and hybrid objects that make his playful visual language and logics tangible. His Light Bulb series of fixtures for the Foscarini lighting company is but the latest example of this.

View gallery

View gallery

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

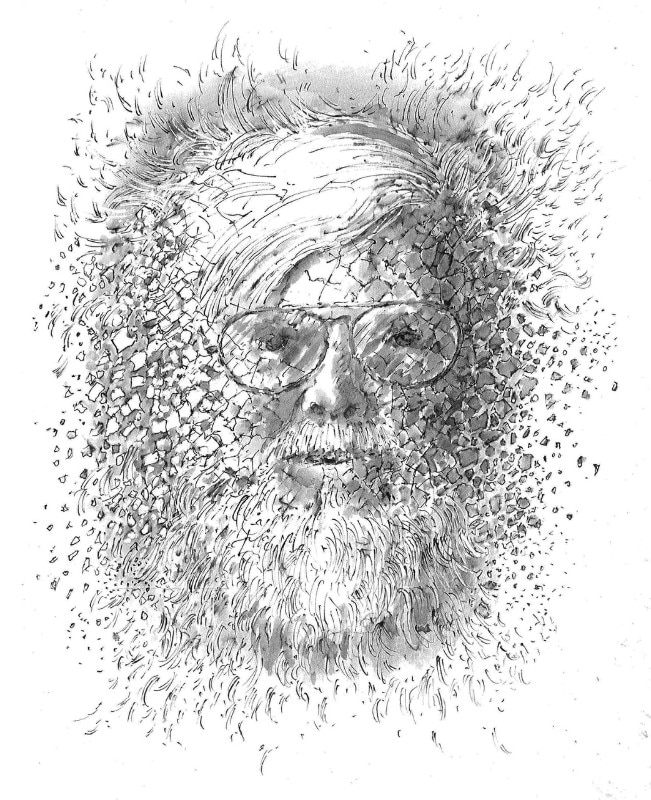

James Wines, modern-day radical

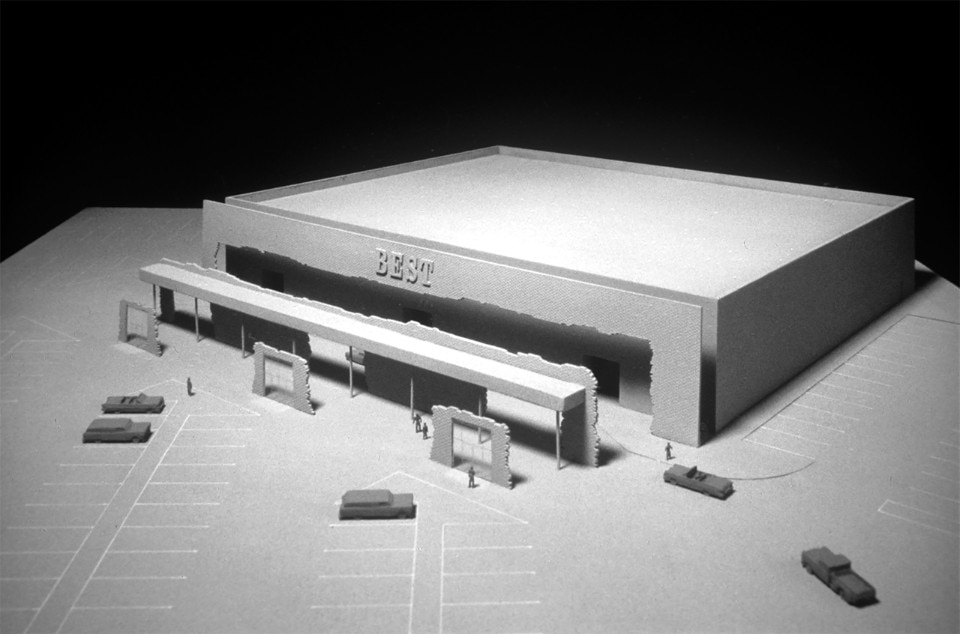

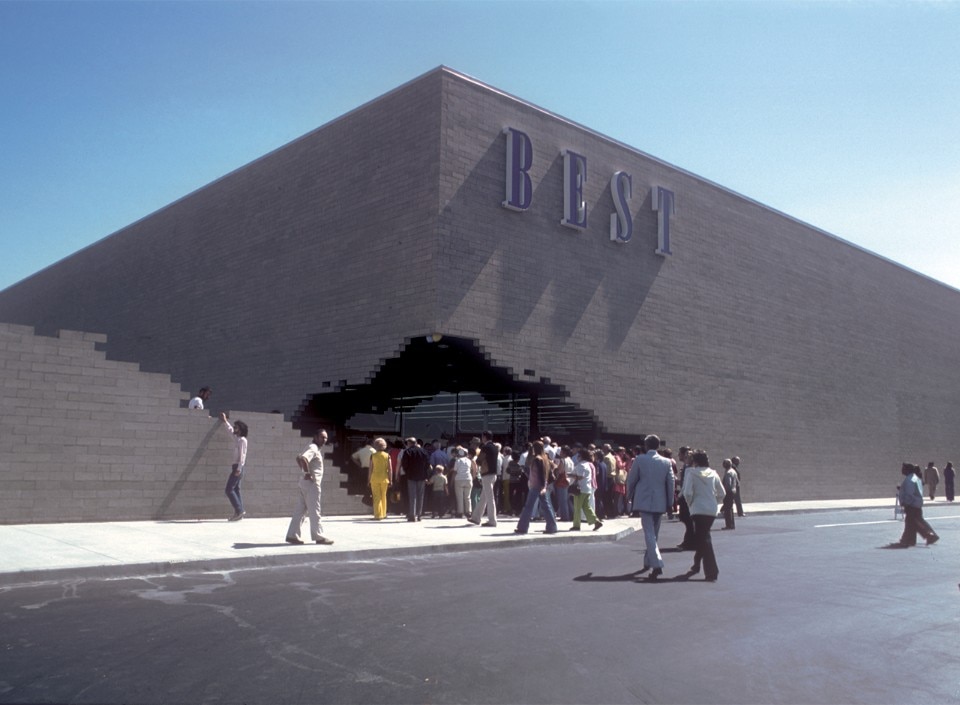

SITE, BEST Anti Sign Building, Richmond VA, USA, 1978. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Anti Sign Building, Richmond VA, USA, 1978. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Cutler Ridge Building, Miami FL, USA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Cutler Ridge Building, Miami FL, USA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Cutler Ridge Building, Miami FL, USA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

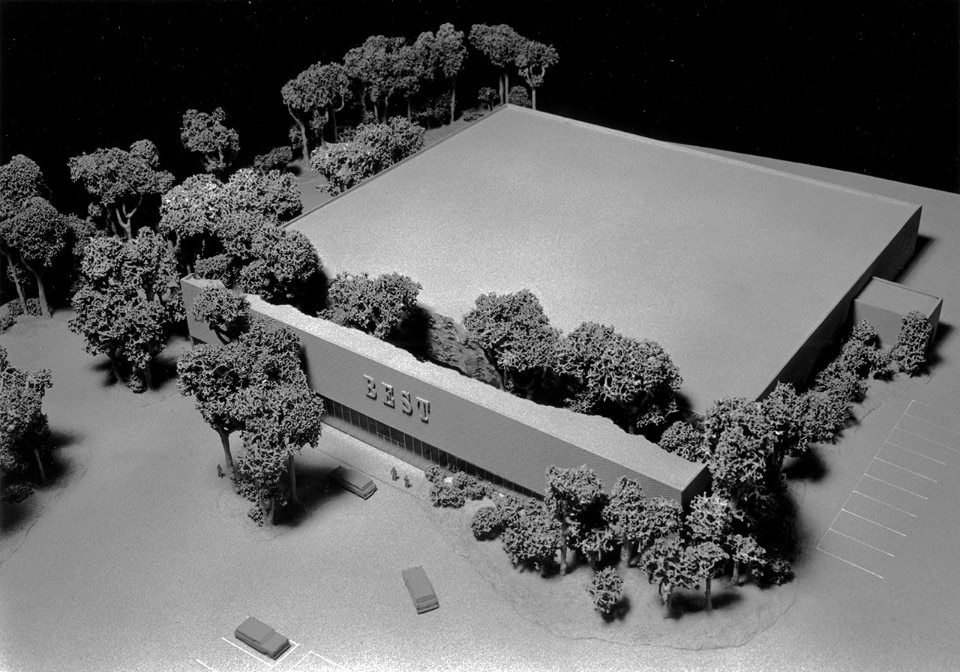

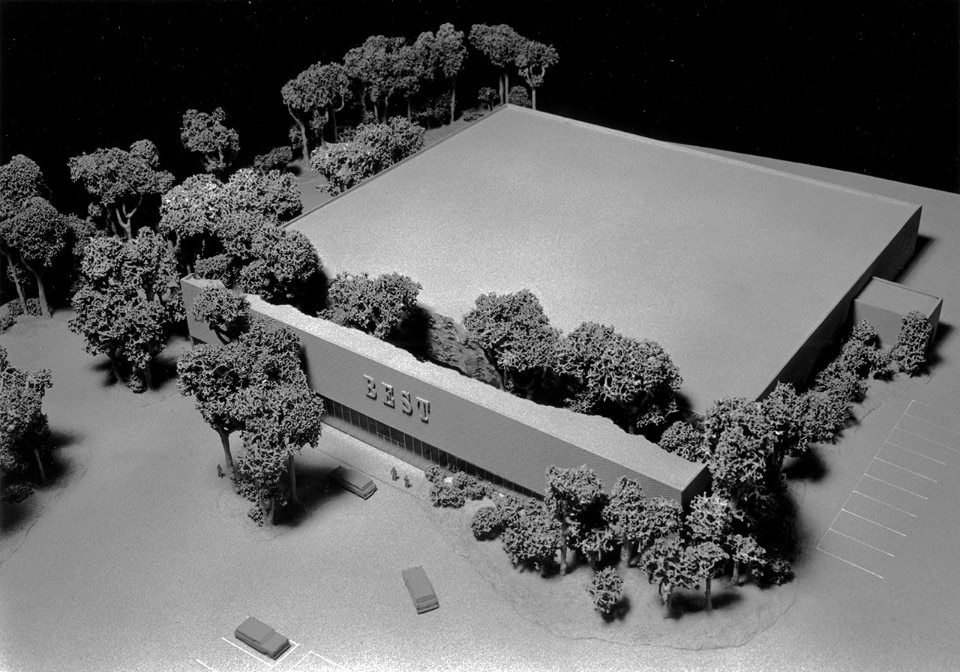

SITE, BEST Forest Building, Richmond VA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Forest Building, Richmond VA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Forest Building, Richmond VA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Forest Building, Richmond VA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Forest Building, Richmond VA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

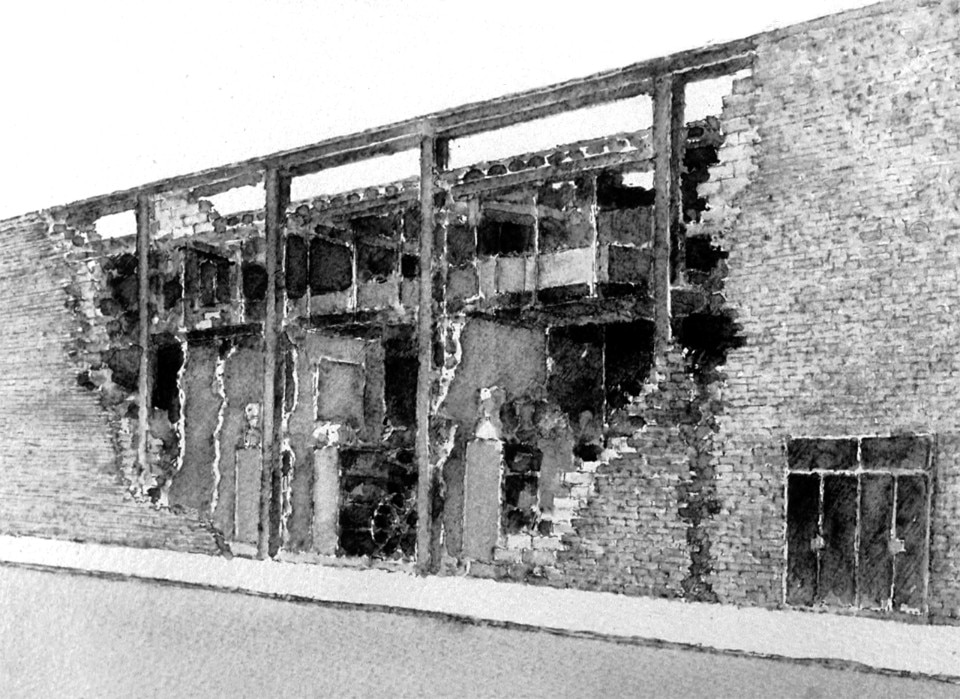

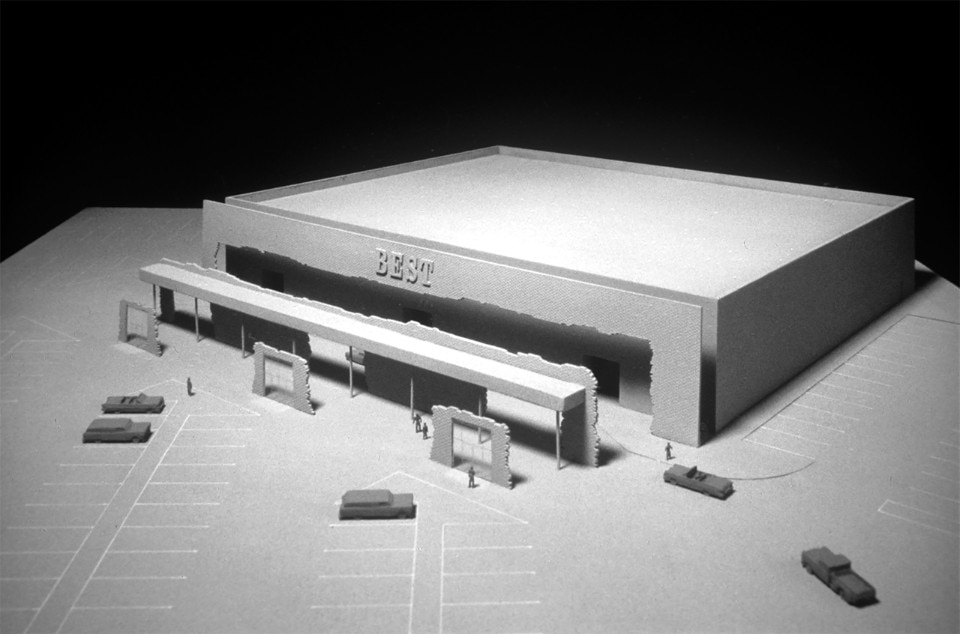

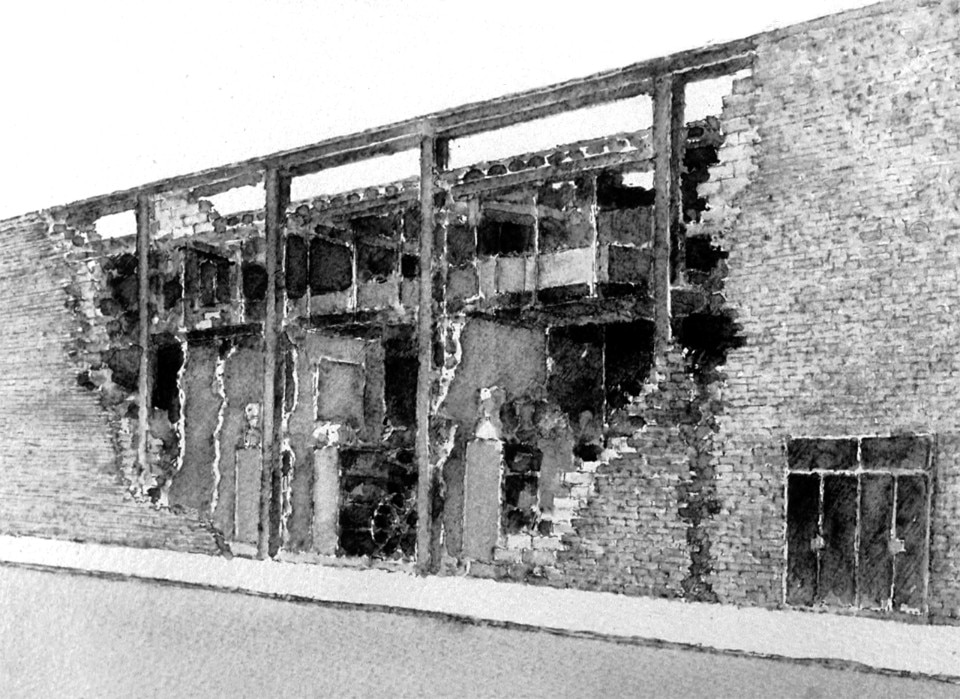

SITE, BEST Indeterminate Facade, Houston, TX 1974. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Indeterminate Facade, Houston, TX 1974. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Indeterminate Facade, Houston, TX 1974. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Inside Outside Building, Milwaukee, WI 1984. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Inside Outside Building, Milwaukee, WI 1984. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Inside Outside Building, Milwaukee, WI 1984. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Inside Outside Building, Milwaukee, WI 1984. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

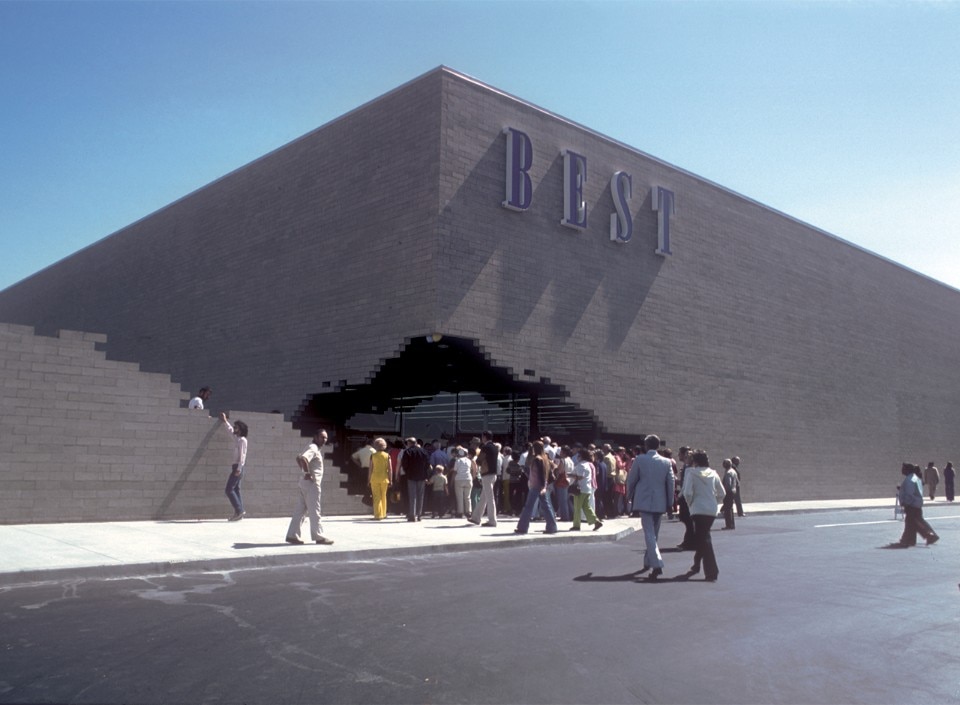

SITE, BEST Notch Building, Sacramento, CA, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Notch Building, Sacramento, CA, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Notch Building, Sacramento, CA, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Notch Building, Sacramento, CA, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

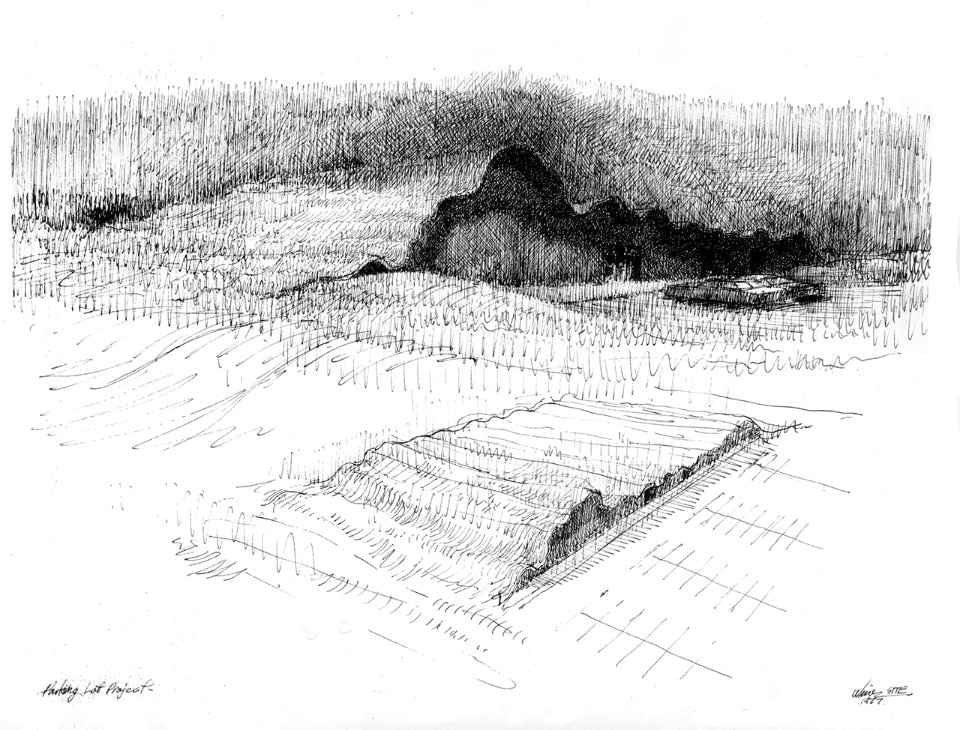

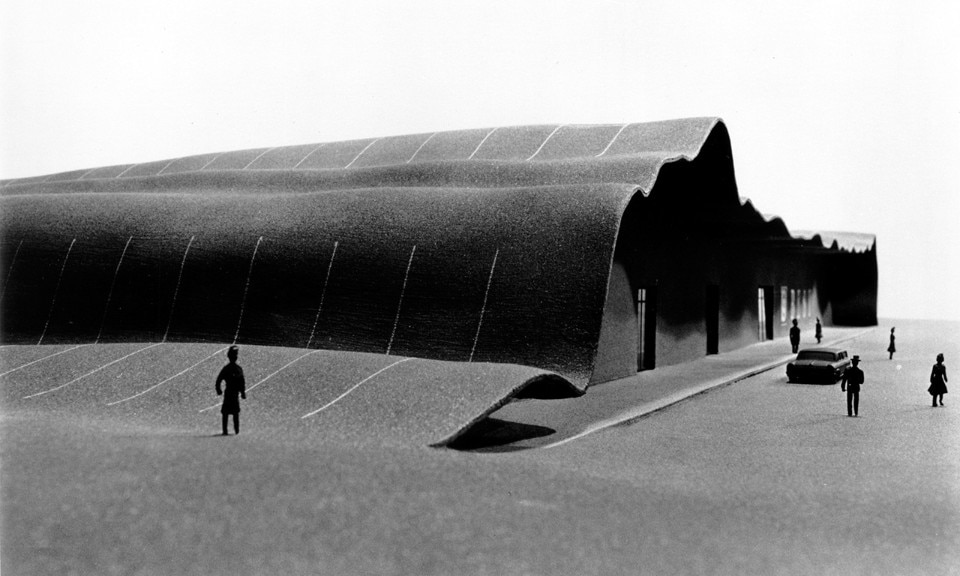

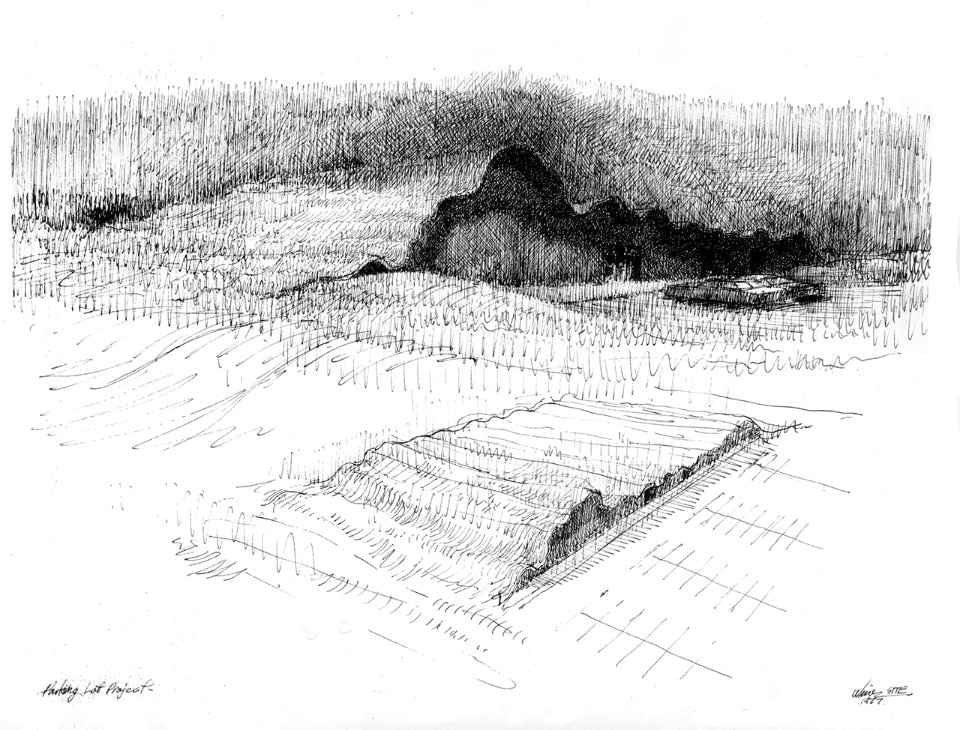

SITE, BEST Parking Lot, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Parking Lot, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

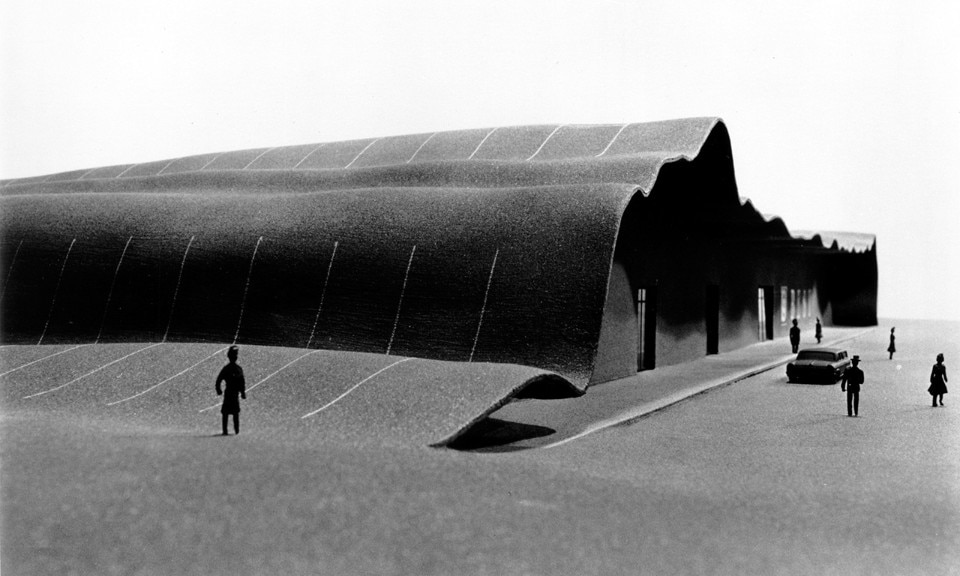

SITE, BEST Rainforest Building, Hialeh, FL 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Rainforest Building, Hialeh, FL 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Rainforest Building, Hialeh, FL 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

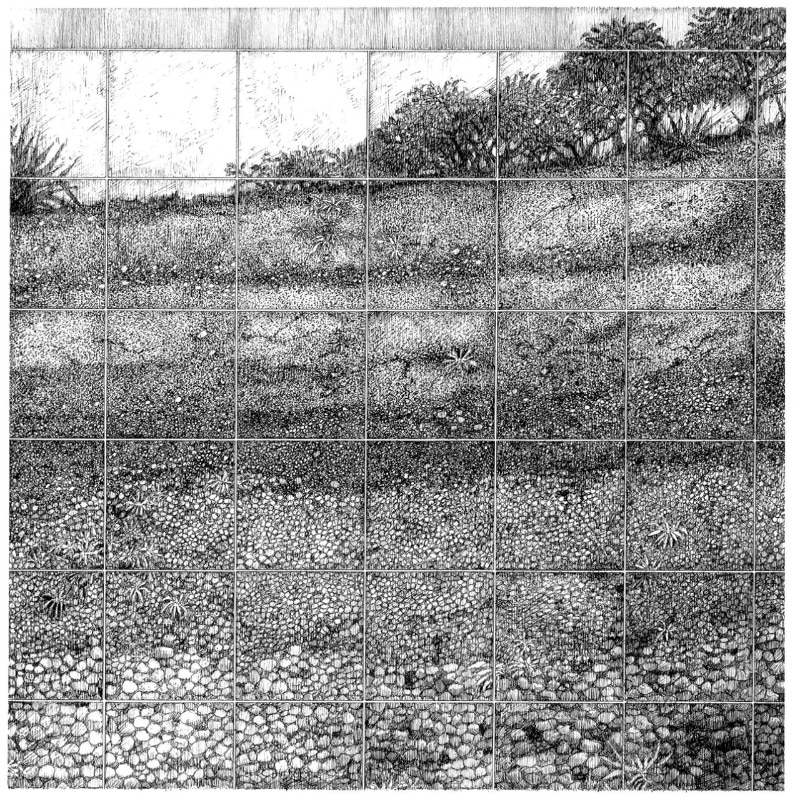

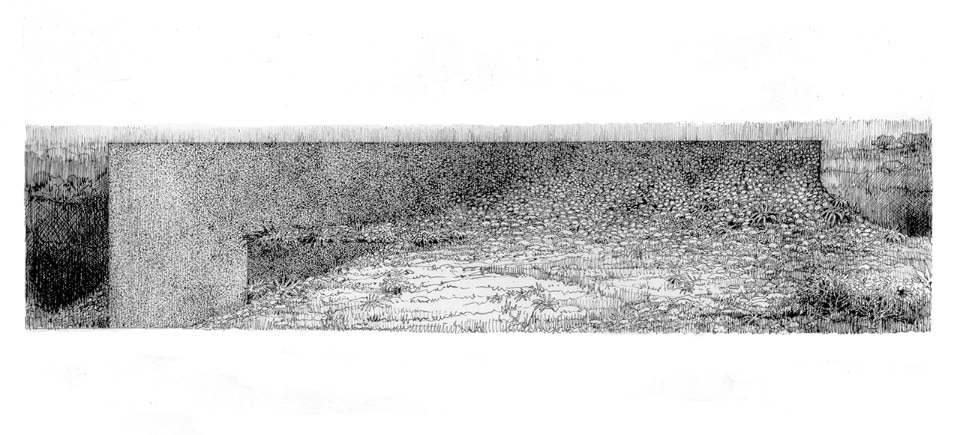

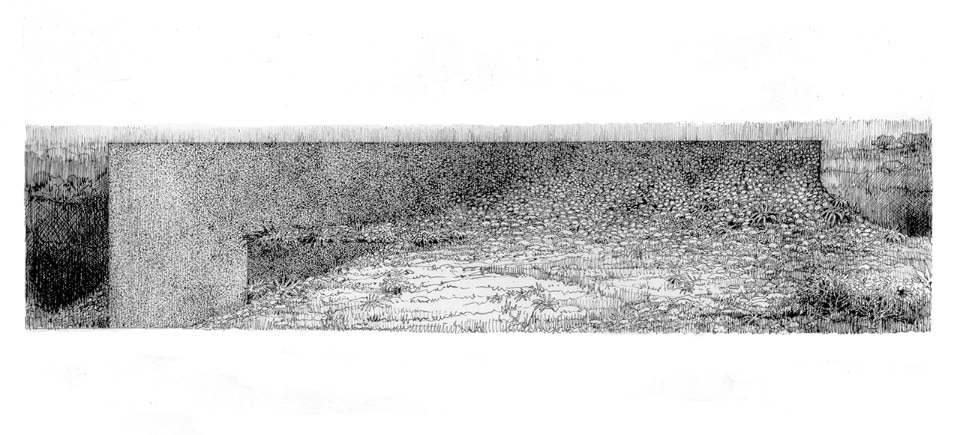

SITE, BEST Terrarium, 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Terrarium, 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Anti Sign Building, Richmond VA, USA, 1978. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Anti Sign Building, Richmond VA, USA, 1978. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Cutler Ridge Building, Miami FL, USA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Cutler Ridge Building, Miami FL, USA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Cutler Ridge Building, Miami FL, USA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Forest Building, Richmond VA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Forest Building, Richmond VA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Forest Building, Richmond VA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Forest Building, Richmond VA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Forest Building, Richmond VA 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Indeterminate Facade, Houston, TX 1974. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Indeterminate Facade, Houston, TX 1974. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Indeterminate Facade, Houston, TX 1974. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Inside Outside Building, Milwaukee, WI 1984. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Inside Outside Building, Milwaukee, WI 1984. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Inside Outside Building, Milwaukee, WI 1984. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Inside Outside Building, Milwaukee, WI 1984. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Notch Building, Sacramento, CA, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Notch Building, Sacramento, CA, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Notch Building, Sacramento, CA, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Notch Building, Sacramento, CA, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Parking Lot, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Parking Lot, 1977. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Rainforest Building, Hialeh, FL 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Rainforest Building, Hialeh, FL 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Rainforest Building, Hialeh, FL 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Terrarium, 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Nine projects for BEST buildings by SITE

James Wines, modern-day radical

SITE, BEST Terrarium, 1979. Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Your personal and professional life is full of references to Italy. How did this link develop?

I lived in Rome when I was young, when many American artists lived there, too, like Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly and Rinaldo Paluzzi. We all lived in the Trastevere district, when the city was not as expensive as it is today. My studio was on Via San Michele. Those were intensive years, and I kept in touch with many of those people. In the same period, I got to know the groups Archizoom, Superstudio and UFO in Milan and Florence. In particular, I became acquainted with Gianni Pettena, Andrea Branzi and Michele De Lucchi. Pierre Restany and Bruno Zevi wrote my first monograph, SITE: Architecture as Art (St. Martin’s Press, New York City 1980).

View gallery

View gallery

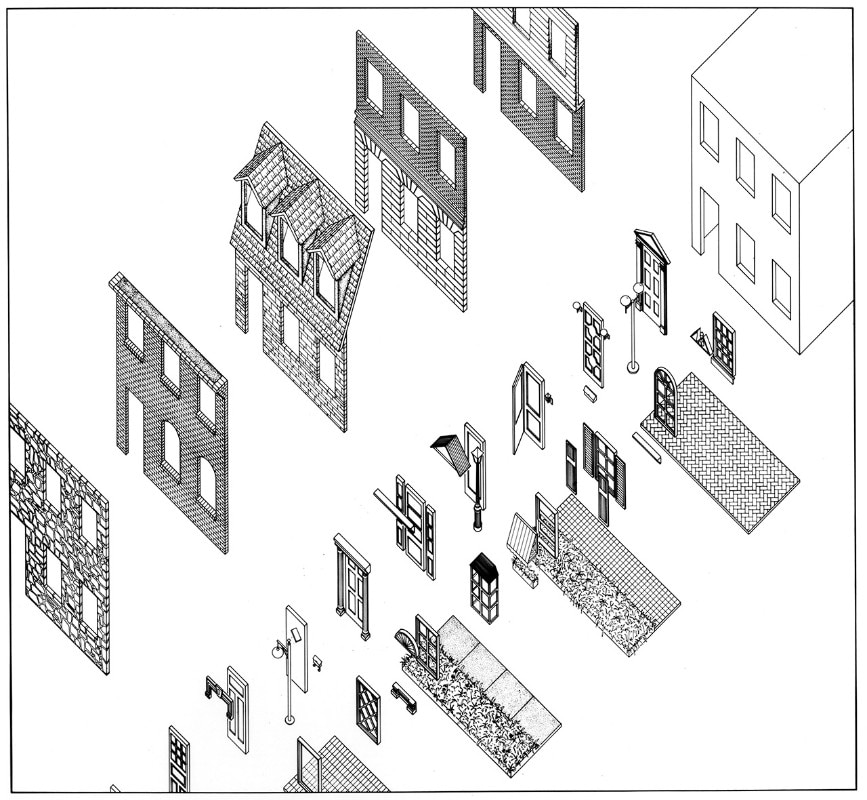

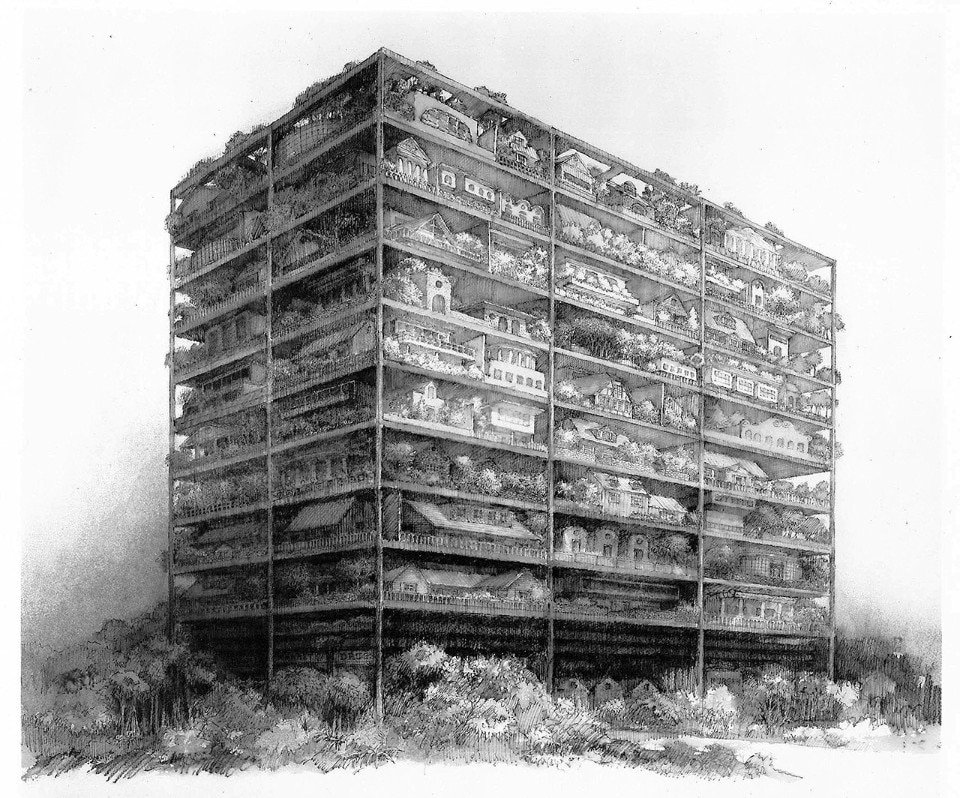

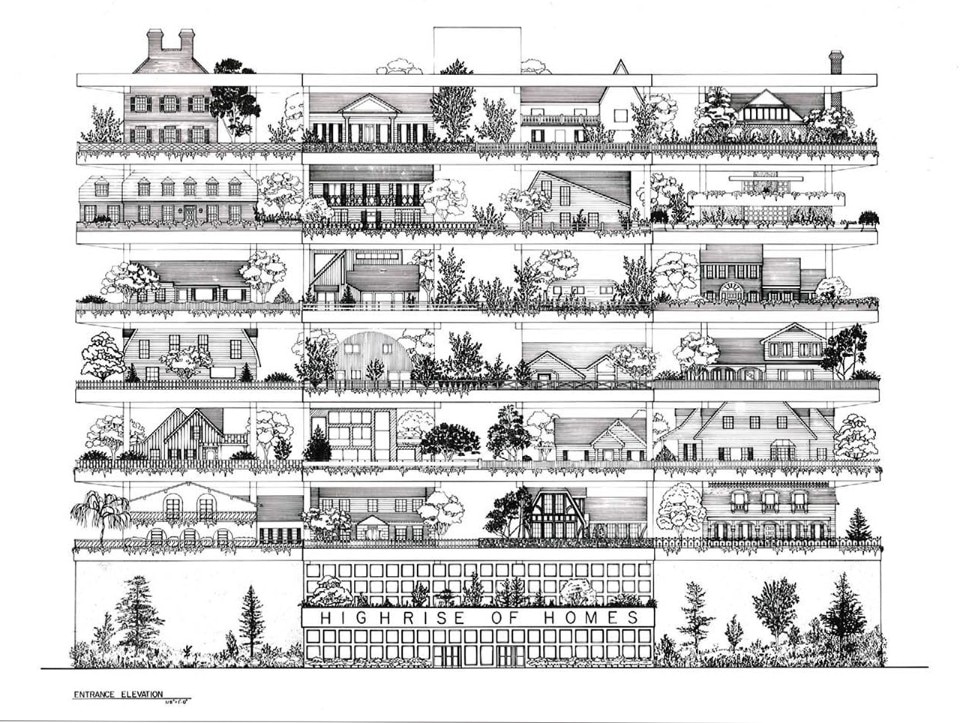

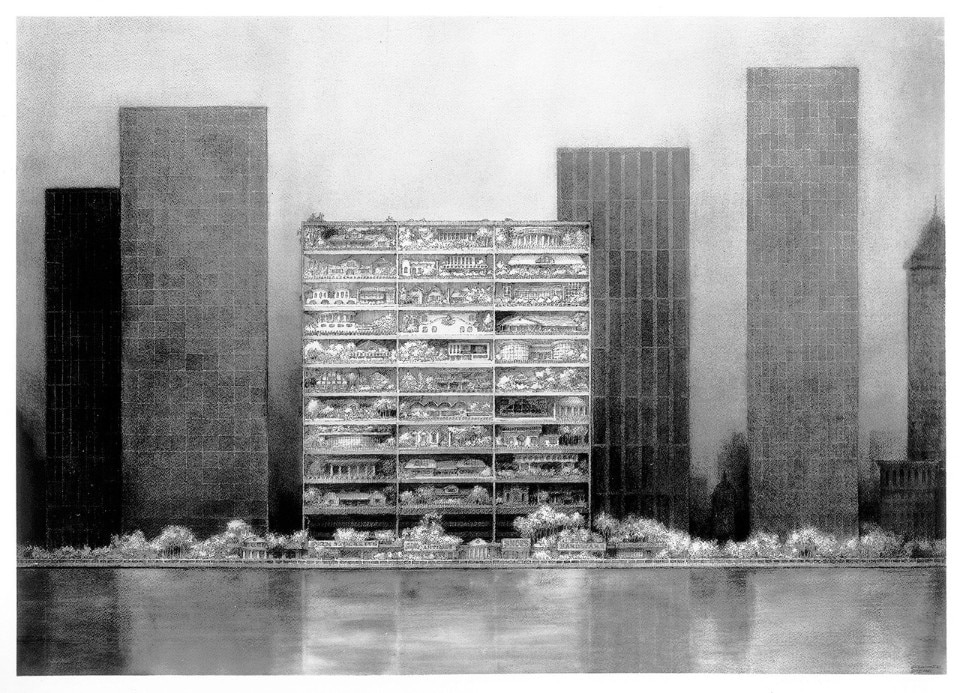

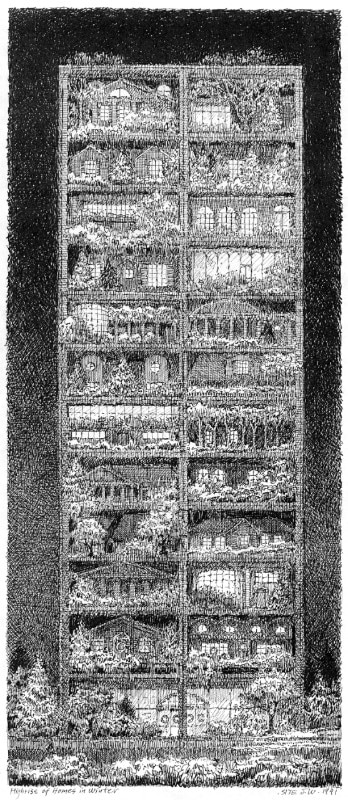

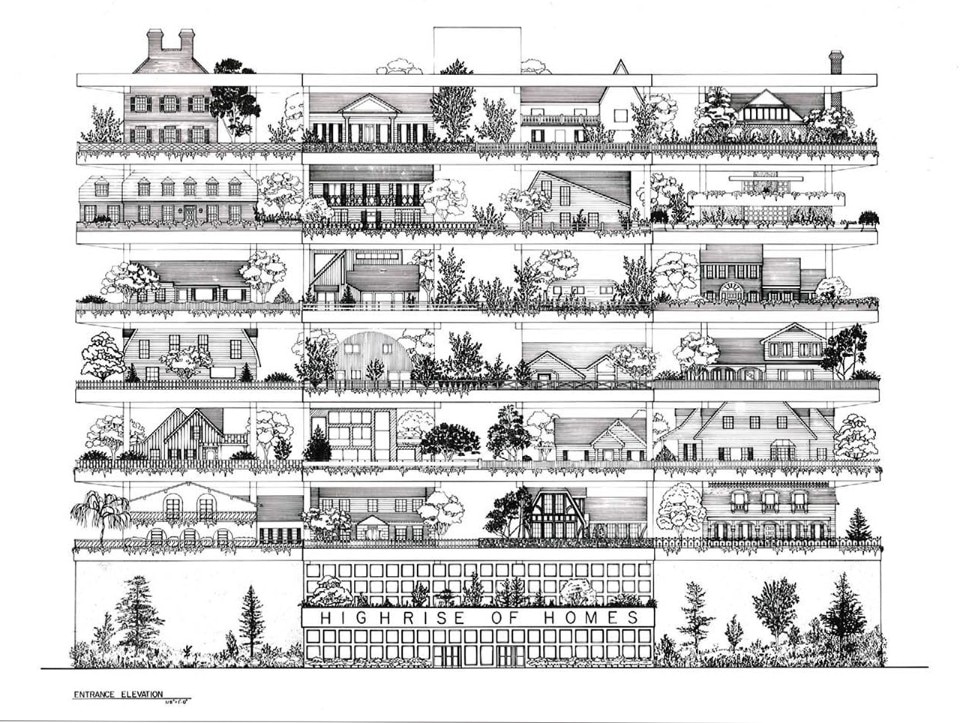

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

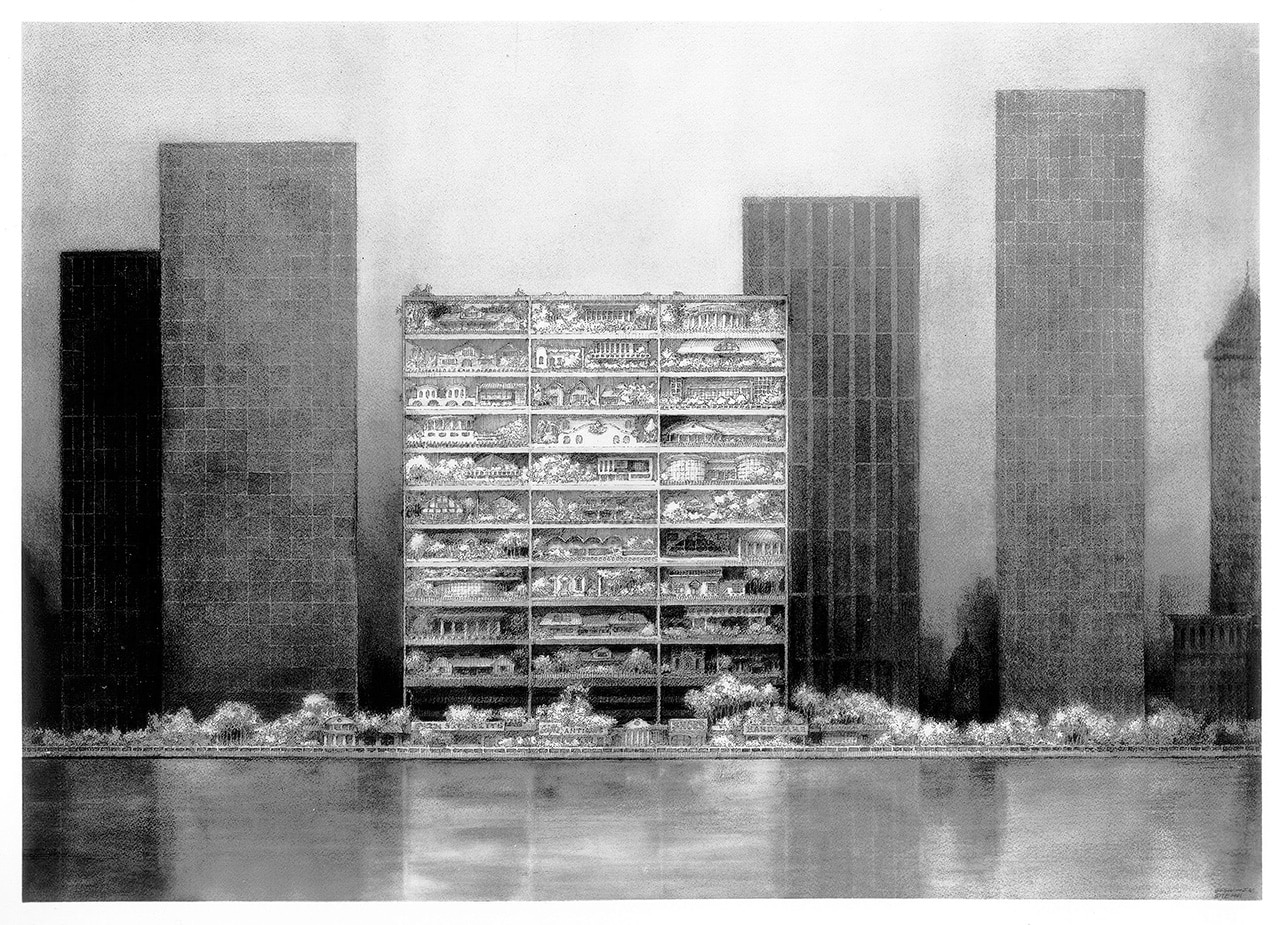

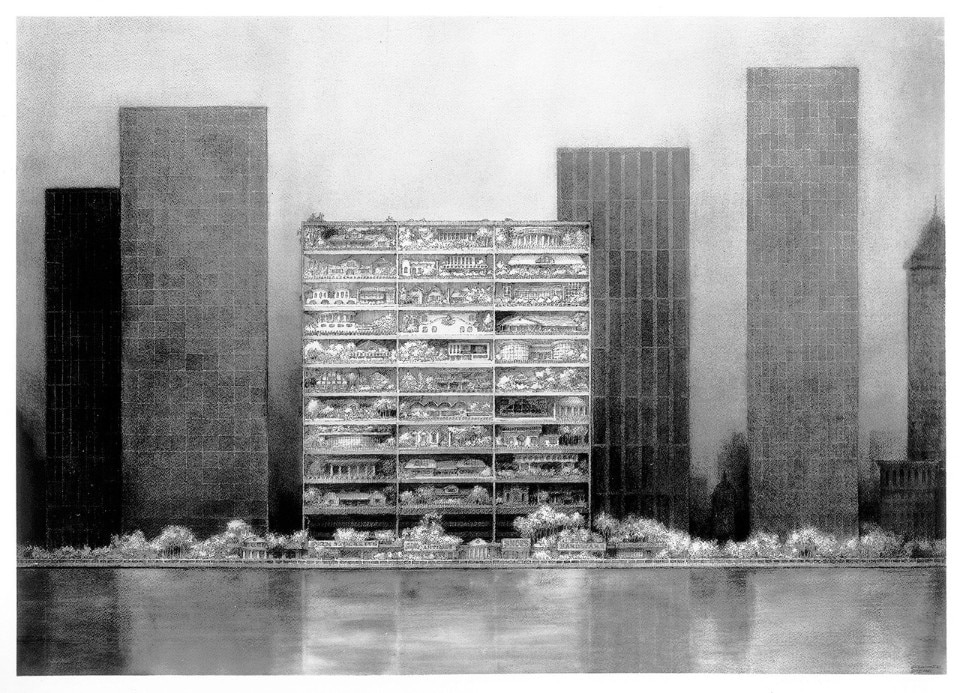

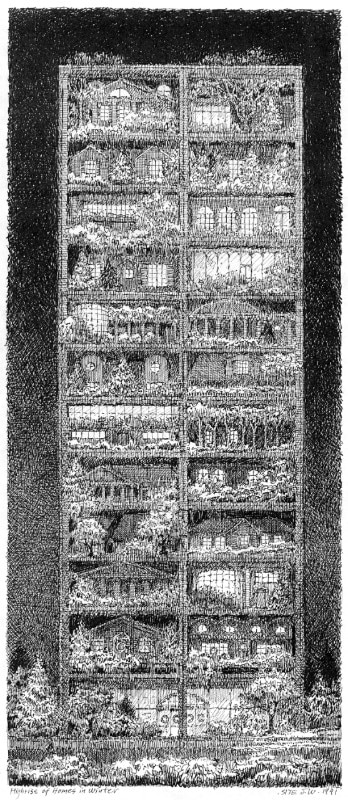

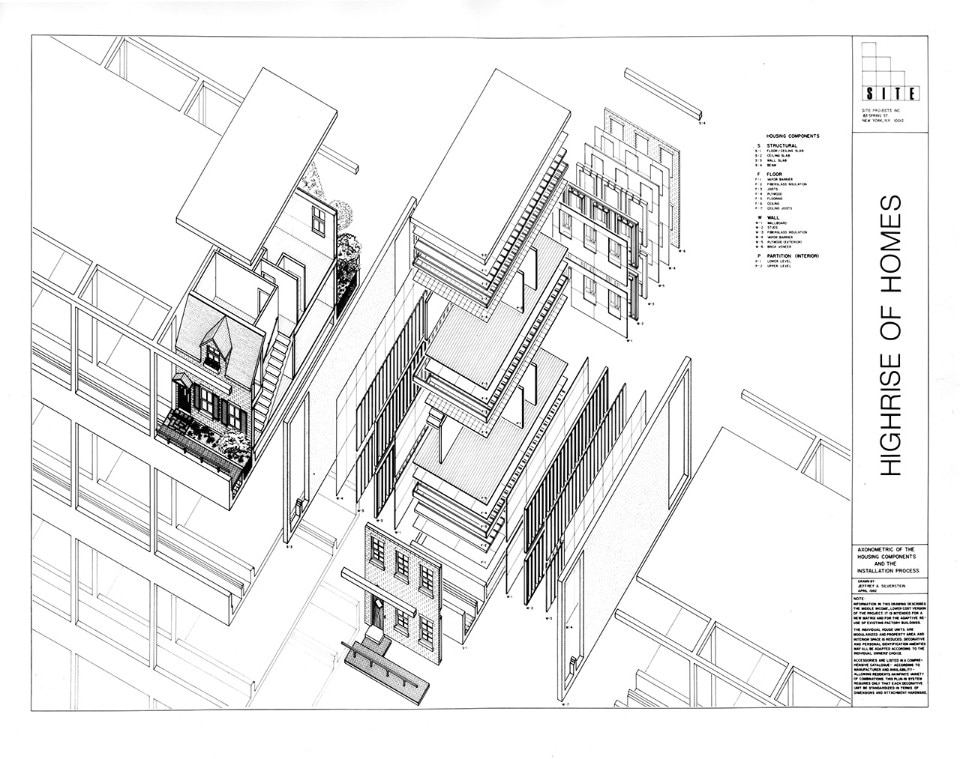

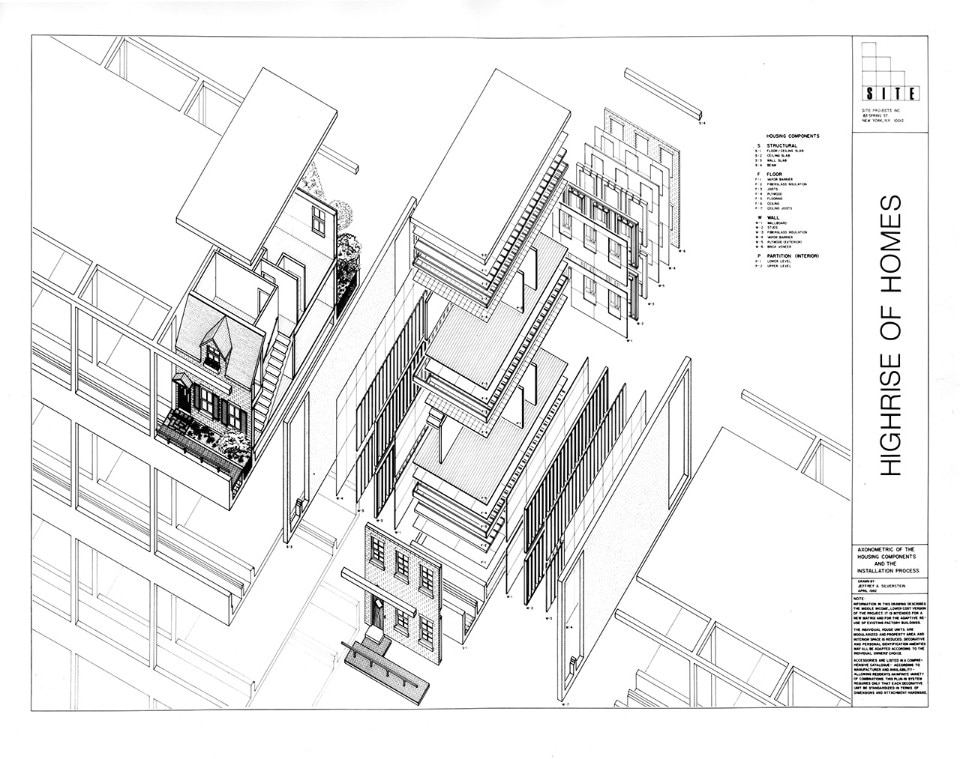

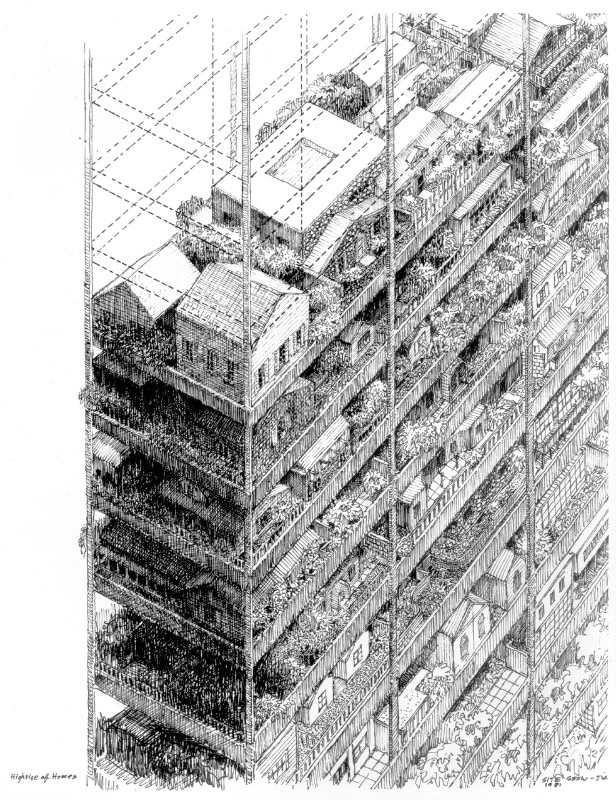

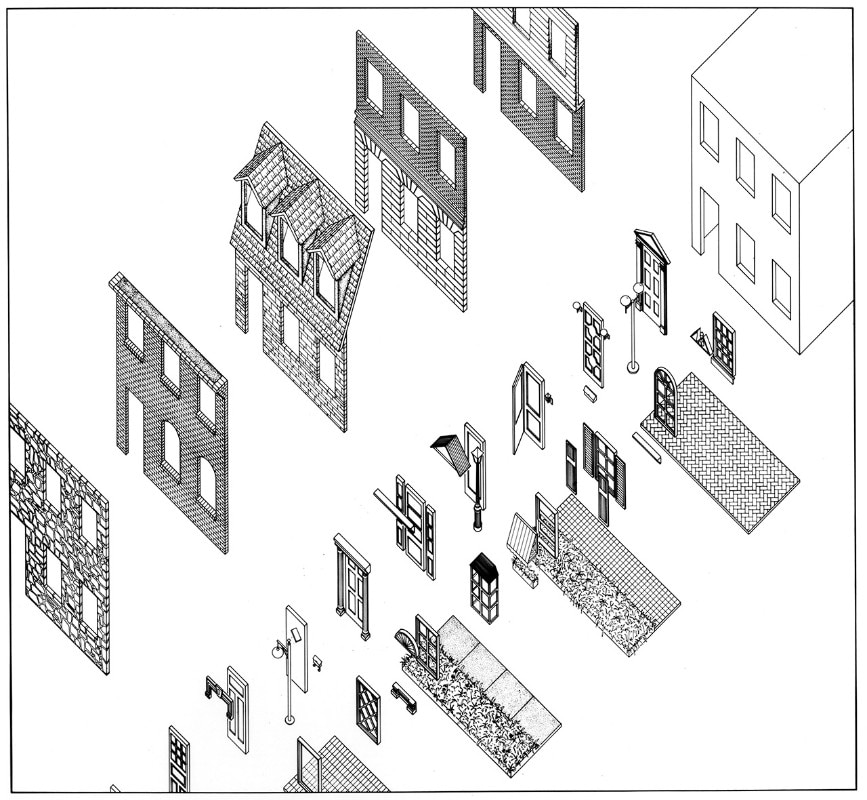

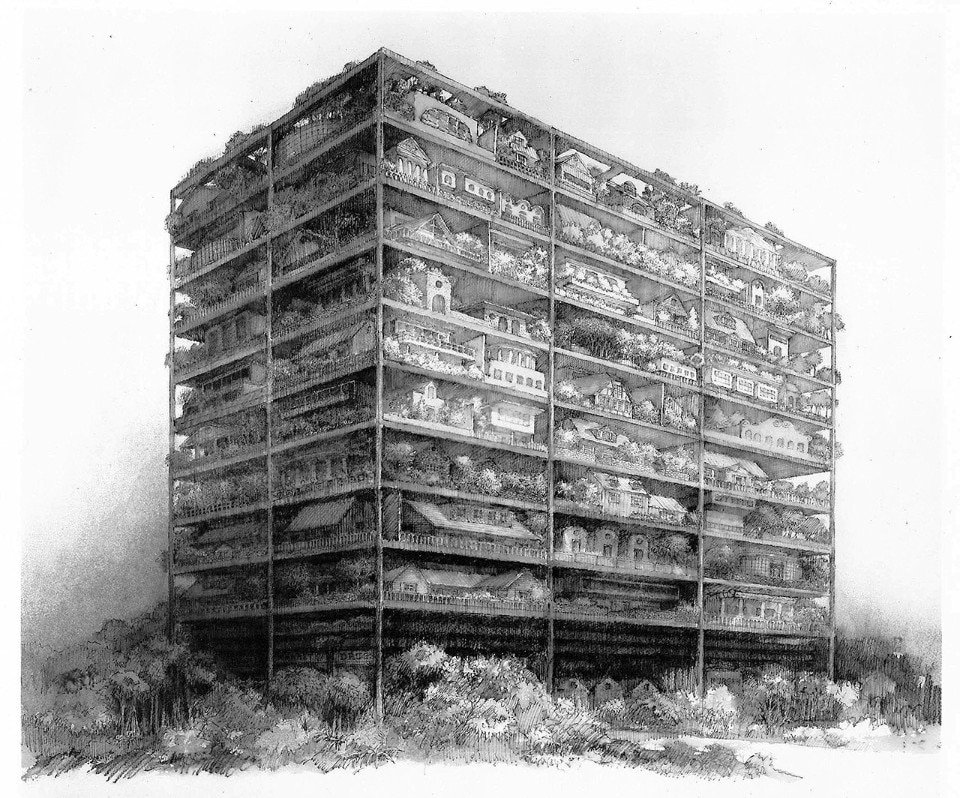

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

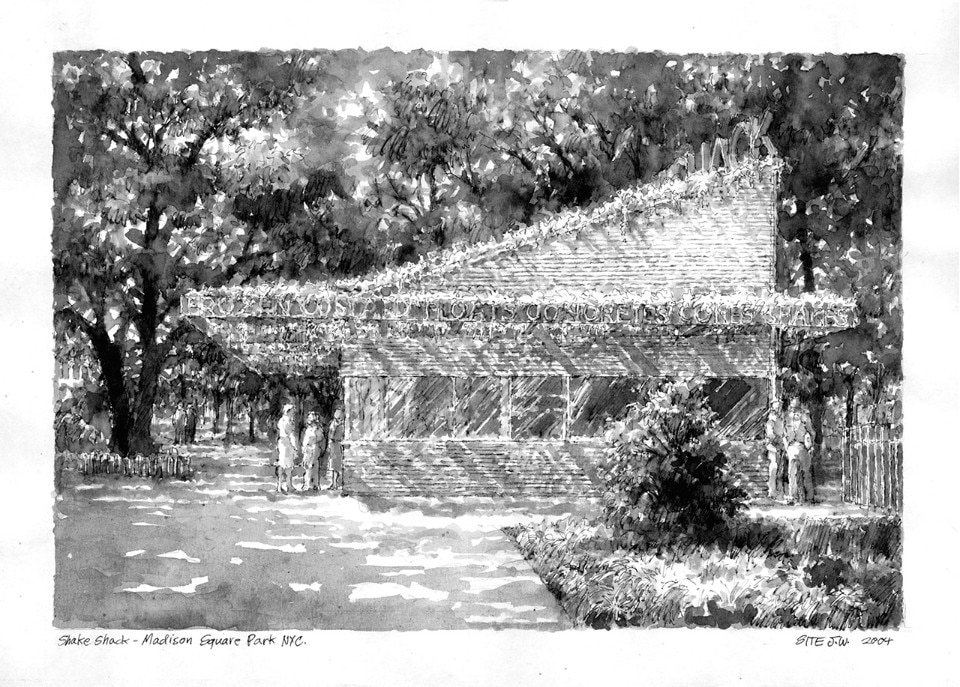

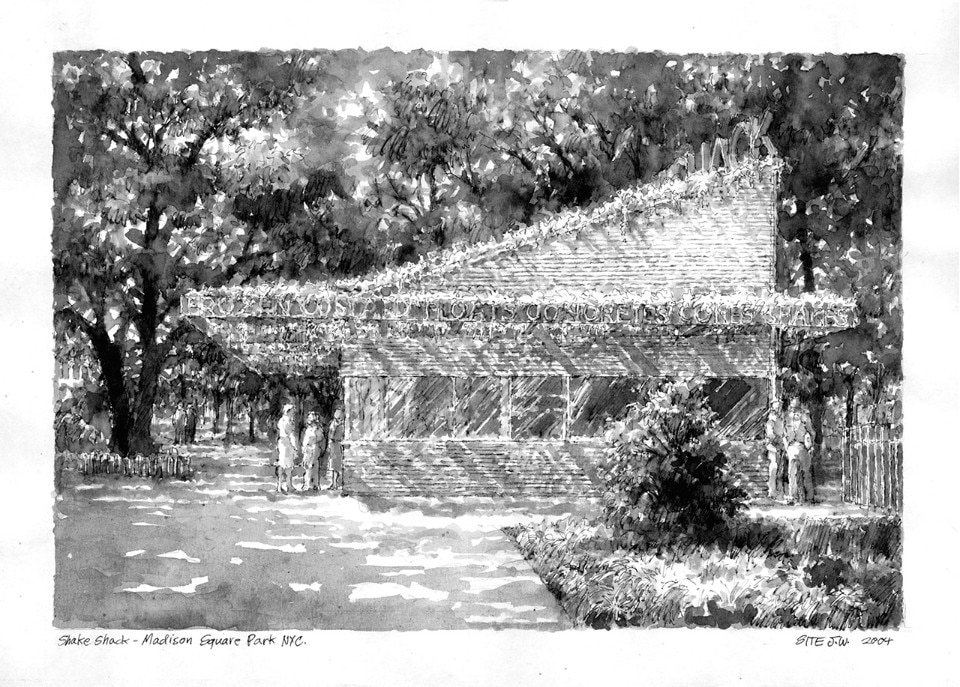

SITE, Shake Shack, New York, USA, 2004. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

SITE, Shake Shack, New York, USA, 2004. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

James Wines, Shake Shack. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Horoscope Ring, Toyama, Japan (1992). Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Horoscope Ring, Toyama, Japan (1992). Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Horoscope Ring, Toyama, Japan (1992). Courtesy James Wines, SITE

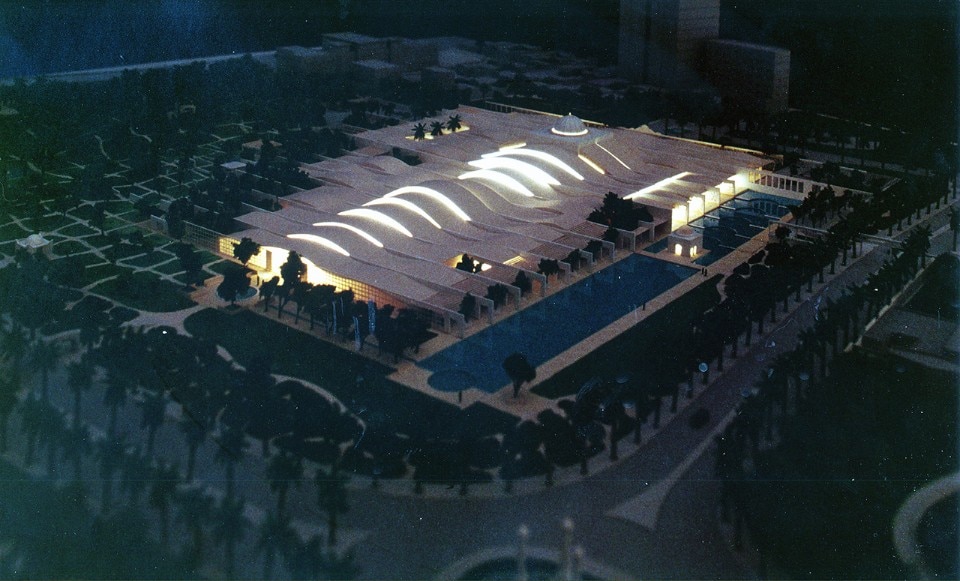

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

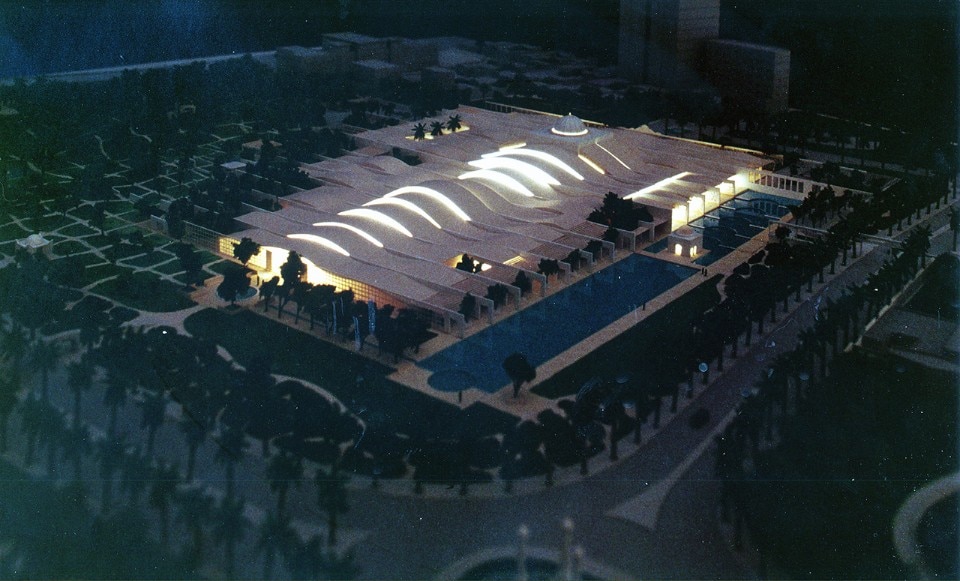

SITE, Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

SITE, Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

SITE, Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Highrise of Homes. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

SITE, Shake Shack, New York, USA, 2004. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

SITE, Shake Shack, New York, USA, 2004. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

James Wines, Shake Shack. Courtesy SITE, James Wines

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Horoscope Ring, Toyama, Japan (1992). Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Horoscope Ring, Toyama, Japan (1992). Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Horoscope Ring, Toyama, Japan (1992). Courtesy James Wines, SITE

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

SITE, Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

SITE, Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

Architecture according to James Wines

Highrise of Homes, Shake Shack in New York (2004), Horoscope Ring in Toyama, Japan (1992) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

SITE, Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (unbuilt, 1997)

The Domus archive contains pages showing trips to New York taken by Alessandro Mendini, Andrea Branzi and Pierre Restany in 1983. The year after, SITE was invited to a seminar at Domus Academy in Milan. What ideas did you share?

Those days, our most urgent task was to find alternatives to the modern movement, which was being taught dogmatically at universities. That was our biggest contact point, meaning an interest in experimentation and the dissolution of lines separating architecture, design and art. In 1970, I went to New York to set up shop, but our interaction continued. Over the years, I worked with a few Italian manufacturers, designing products. The recent surge in interest for that period in time – for the Radical movement and its ideology – is justified by the need to experiment. For me, the priority has always been art over technique. If the technical execution is perfect, but there is no idea guiding its meaning, then there is no interest, because art is lacking. I like to quote my European reference figures regarding matters of culture. In this case, I’d opt for Oscar Wilde, who said, “An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all.”

There is similarity between the Archizoom proposal for the 1970 World Expo in Osaka and your design for the Museum of Islamic Arts in Doha, Qatar. Also between the Archizoom project No-Stop City and your buildings for the Best Products Company.

These are the type of idea that circulated among us. There was a spontaneous sharing of views, subject matter and aims. I was greatly influenced by environmental art, too, for instance the work of Robert Smithson. Germano Celant was a key figure in this regard for being a bridge between Italy and the United States. That’s why I named my office Sculpture in the Environment – SITE for short. It refers to an object inserted in the landscape to establish reciprocal exchange with people.

What is the story of your design products for Italian manufacturers?

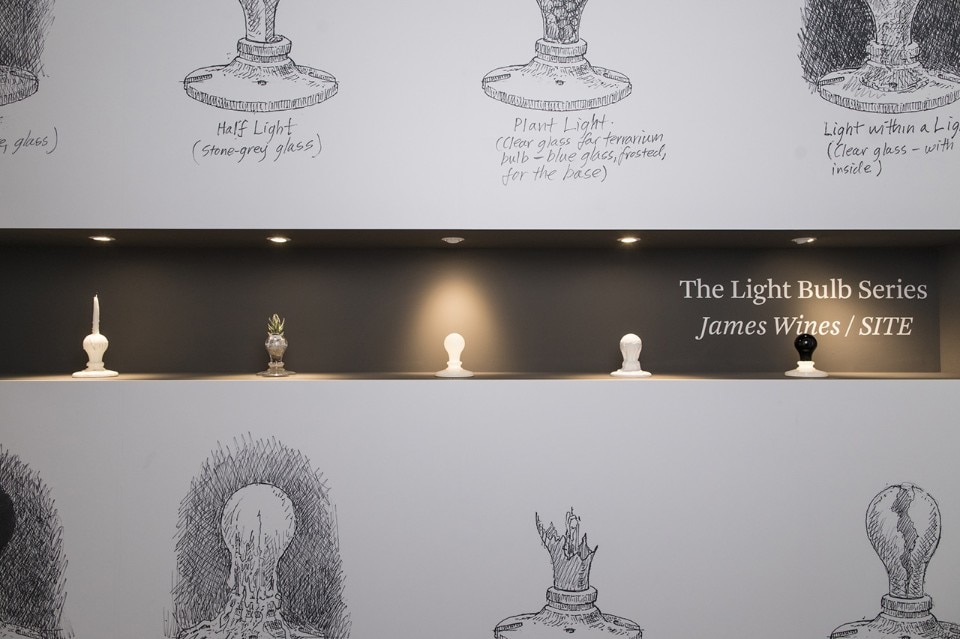

Most of my work for Italian companies was made for instalments of the Venice Biennale and the Triennale di Milano, so it was not conceived for serial production. With Foscarini, we attempted to maintain the sense of experimentation and transfer it to industrially made lamps. I liked the idea of taking an elementary object and creating variations. The light bulb is something we don’t think of often. It’s banal yet iconic. It’s meaning is light. We began this project for the Abitare il Tempo trade show in Verona way back in 1991, and recently returned to industrialise it.

View gallery

View gallery

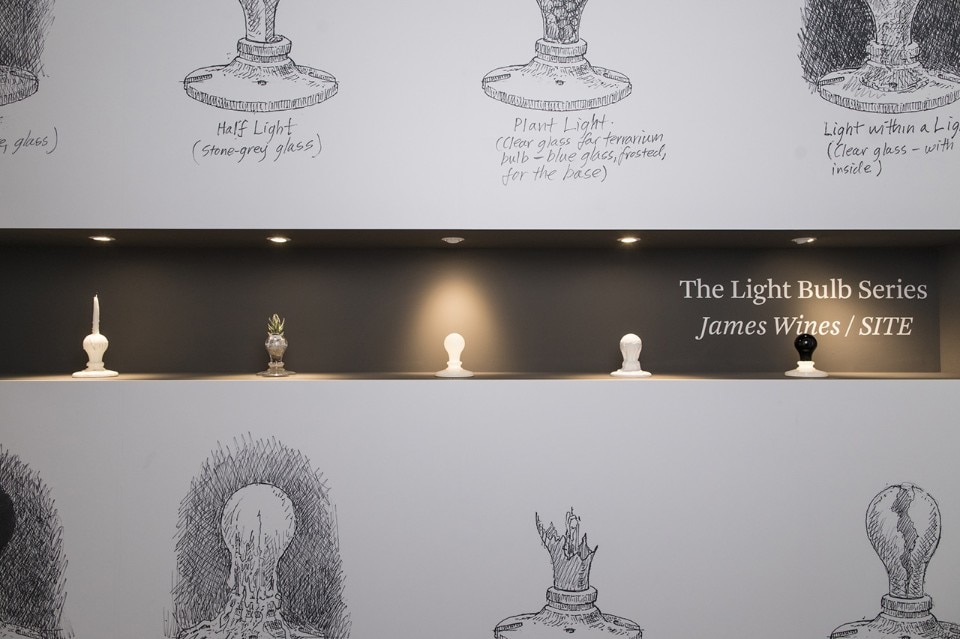

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Black Light, James Wines, Foscarini, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Candle Light, James Wines, Foscarini, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Melting Light, James Wines, Foscarini, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Plant Light, James Wines, Foscarini, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

White Light, James Wines, Foscarini, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

James and Suzan Wines at Reverse Room installation, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

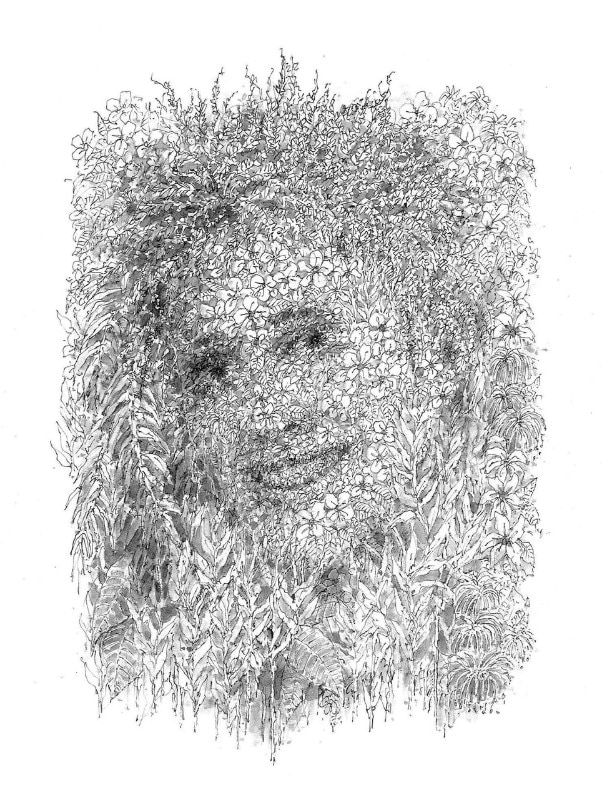

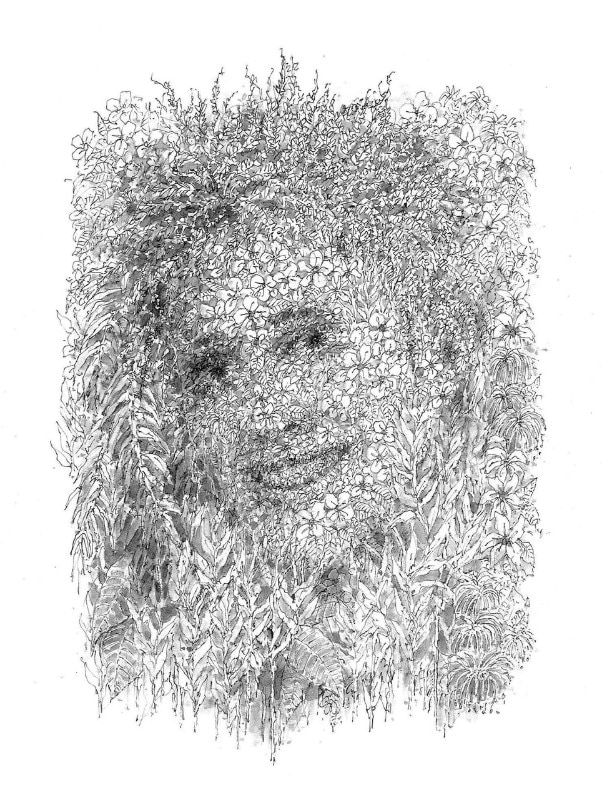

James Wines, portrait of Suzan Wines, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Black Light, James Wines, Foscarini, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Candle Light, James Wines, Foscarini, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Melting Light, James Wines, Foscarini, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Plant Light, James Wines, Foscarini, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

White Light, James Wines, Foscarini, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

Reverse Room, James and Suzan Wines, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

James and Suzan Wines at Reverse Room installation, Foscarini Spazio Brera, 2018

The Light Bulb Series

James Wines designs for Foscarini and the interiors of the brand's flagship store, in collaboration with Suzan Wines

James Wines, portrait of Suzan Wines, 2018

The one called Black Light is a fascinating, magical object. It’s an oxymoron for being the negation of the light bulb’s function.

The departure point for the project was that every part of the object emit light except the light bulb itself. Inversion was the qualifying factor of each of these designs. It follows what preceded: the original.

What connection is there between your design and your architecture?

The light bulb is something you do not want to over-design. You want to under-design it. So the Foscarini collection is not really design, but an inversion, a comment on the object itself. My stores for Best were made along the same lines. Everything we designed was sufficiently minimal as to not make the store unrecognisable in its form of big box, which is a subconscious type of building in American culture. It has specific traits that make it recognisable. If you modify it too much, you over-design it, and it no longer works.