Vienna played a significant role in development of modern architecture and design since Otto Wagner formulated his seminal ideas in his Modern Architecture book in 1896 and Josef Hoffmann with Koloman Moser pioneered a relationship between art, craft and business in their important work behind Wiener Werkstätte, founded in 1903. But early 20th century Art Nouveau and then famous work of Adolf Loos and Josef Frank are not only influences on Vienna 20th century architecture. Some lesser known design movements, originated in Vienna during the second half of the century, tell completely different story on the city architectural legacy. Some of them are still visible in an important and still preserved public interiors and small-scale architectural projects, which can still be visited in Vienna until today.

Soft Modernism of Postwar Vienna

Following Adolf Loos, Josef Frank and Vienna Seccession movement, 1950s Vienna architecture and design were smooth and soft, rather than rigid and geometric. Using decorative elements and organic forms, Vienna mid-century modern played on a sophisticated and refined note of rich palette of materials, and playful shapes. One of the most prolific masters of this period was Oswald Haerdtl (1899-1959), the pupil of Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann.

Some of his interiors and smaller scale architectural projects are still preserved in Vienna. Probably the most famous is a popular Prückel café, remodeled by Haerdtl in 1954. High-ceiling, light-filled space is furnished with the custom-designed seating furniture and lamps, Haerdtl designed in decorative yet organic and streamlined manner. Until today, the Haerdtl‘s interior of the café, right across the MAK museum, remains entirely intact in its original shape.

His another celebrated project include Wien Museum at Karlsplatz, monumental modernist building, completed in 1959. Still operated as a museum, the interior highlights by refined details and surfaces. Anodized aluminum panels, doors and handrails document Haerdtl‘s attention to every custom-designed detail. Another chance to see Oswald Haerdtl‘s architecture in real life offers Volksgarten park, where you can hang-out at Volksgarten Pavillion, designed by the architect between 1947 and 1950.

A small forgotten gem of Austrian 1950s modernism can also be found inside the Prinz Eugen hotel, close to Main Station. Designed by little known architect Georg Lippert in 1958, the hotel with the rhythmical facade and small balconies hides the original interior of the bar, with the smoothly curved wooden chairs, built-in sofas, crystal chandelier and other delicate decorative details, such as sensual gold-colored mirrored niche.

Space-age Futurism of the 1960s

The decorative modernism of the 1950s was a critical point in developing new radical aesthetics and movements of the 1960s and 1970s. One of this year Vienna Design Week venues was open inside former space of a bank at Sparkassplatz, which was designed during the early 1970s by other little known architect Johann Georg Gsteu (1927-2013). One of the member of strong generation of architects, opposing classic modernism, Gsteu designed a striking public space with the circular windows, cut into the 19th century building facade, and dynamic rhythm of the interior with the circular openings and hanging globe lamps. Thanks to Vienna Design Week, this space was discovered for every visitor, who was entering the venue via monumental green door, designed by Gsteu himself as a refined kinetic machine back in the 1980s.

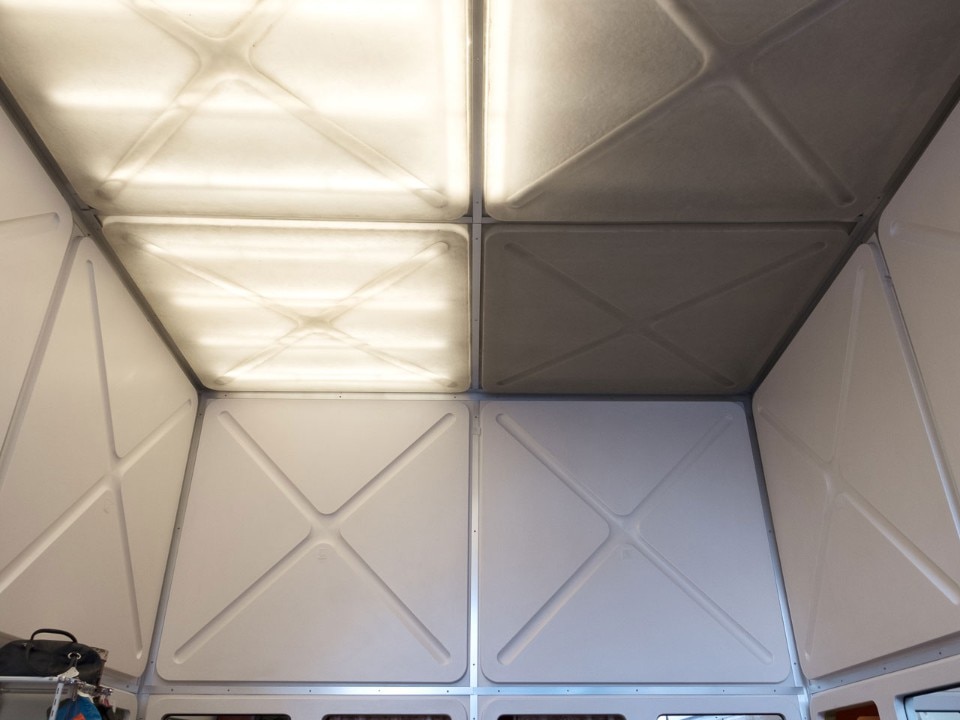

The main representative of the above-mentioned generation of architects, studied under Clemens Holzmeister, was Pritzker prize-winning Hans Hollein (1934-2014), who went long way from his early 1960s space-age designs to the eclectic styles of the 1980s postmodern. His early chapter is represented in Vienna by two small-scale architectural projects, to be found in the center of the city. Retti Candle Shop (designed in 1964) and Christa Metek Boutique (designed in 1966) are small projects where exterior meets interior in one complex design. Lesser known Christa Metek boutique is a futuristic space with the aluminum-covered storefront and dominant circular opening. Inside, one can still find Hollein‘s original built-in plastic displays, storages, light fittings or even individual pieces of furniture. All of this under the tons of vintage Chanel, Valentino and Prada clothes, available in the store today.

Dangerous Architecture of Anti-Design Movement

Hans Hollein belongs to the radical generation of architects, critisizing unhuman side of modernism. Together with Gustav Peichl, Coop Himmelb(l)au, Haus-Rucker-Co or Günther Domenig, they proposed architecture of life and death, symbolically. According to their ideas, architecture should attack the user, stimulate his everyday activities and even hurts by its expressive forms and spiky shapes. They completely denied „boring styles“ of modernism to shock and attack.

This idea of dangerous and anti-architecture is presented in two other significant projects of the 1970s. Hollein designed his other storefront at Am Graben in 1972-1974 for jewelry company Schullin as a wild composition of granite slabs and brass plates to achieve almost barbaric and brutal appearence. The facade of the store reminiscents rock natural forms, with the scarf going through, looking like destroyed or unfinished design.

Project of a Zentralsparkasse bank, completed by Günther Domenig (1934-2012) in 1979, works with the similar concept. While the facade of the bank looks like some dangerous sci-fi robotic creature, the interior was designed as a combination of rough steel high-tech structure, exposed technical features and concrete organic forms, protruding each other. You can still visit the interior of the bank, where cheap clothes is sold today and discover many original features of the interior. The most striking one is probably a concrete gigantic hand, symbolizing the power of the architecture which can also be alive and hurt our body and soul, as architects of radical Vienna design movements of the 1960s and 1970s proposed.

© all rights reserved