Architecture featured in the cinema has always been a source of great fascination, removed as it is from the indifference of daily life. The reason lies in the transcendent strength of the framing, within the geometric limits of which objects and buildings are transformed into things charged with devotion and symbolism, able to “show the subject itself overturned”, as Remo Bodei wrote in The life of things, the love of things (Fordham University Press).

Like the vagina-purse shown in the first few minutes of Marnie, or the existential EUR in Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Eclisse. These are shown in a narrative process that despite being evident, given its physical projection onto a screen, almost appears elusive in its disclosure. This consequently forces the spectator to watch repeatedly, in search of a replication of pleasure.

View gallery

View gallery

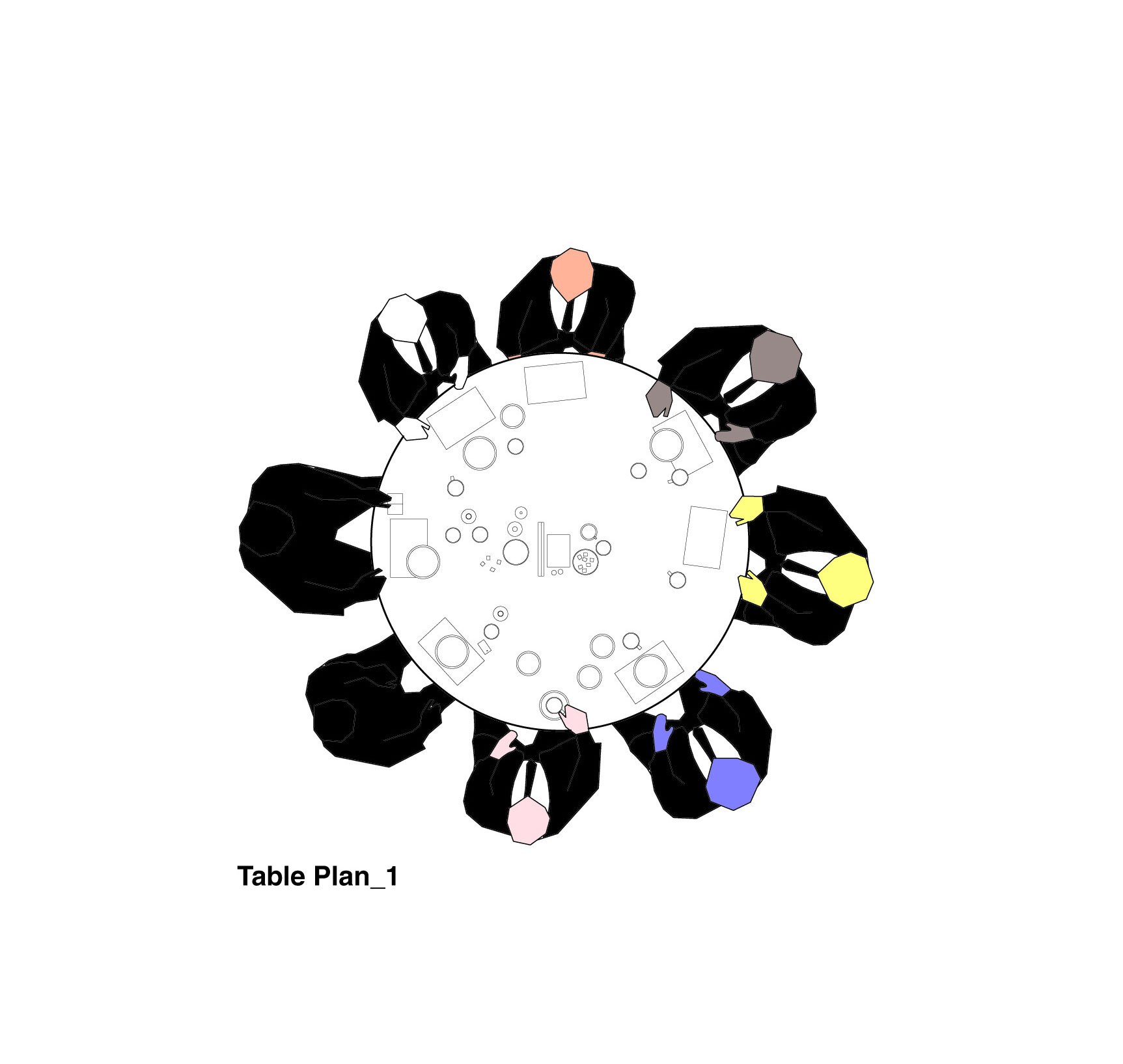

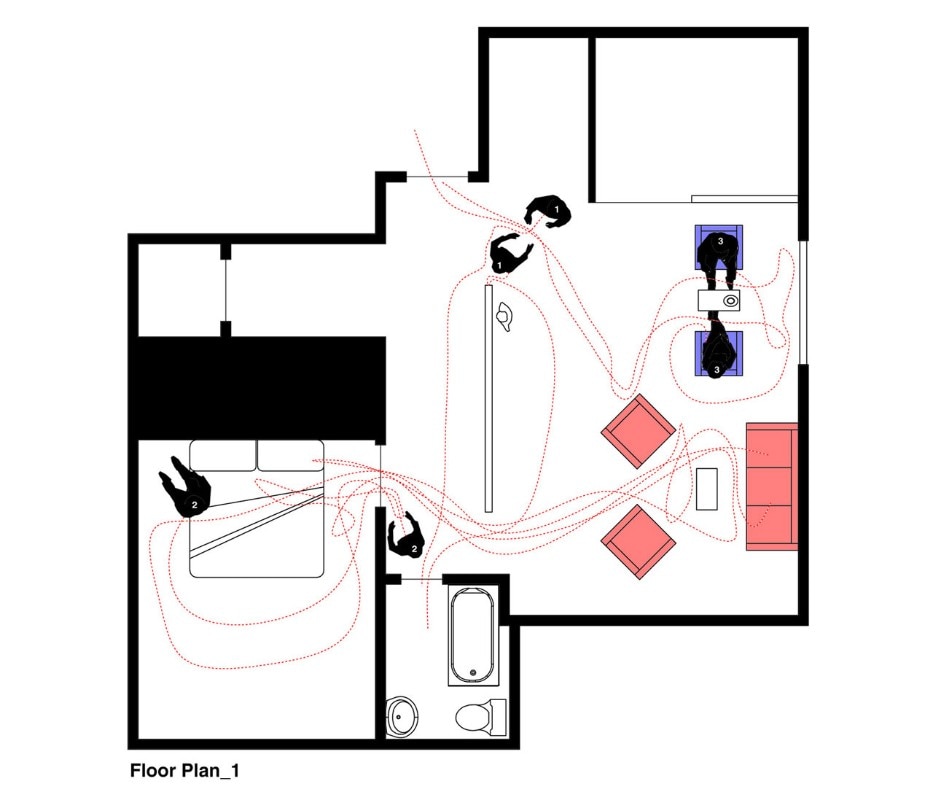

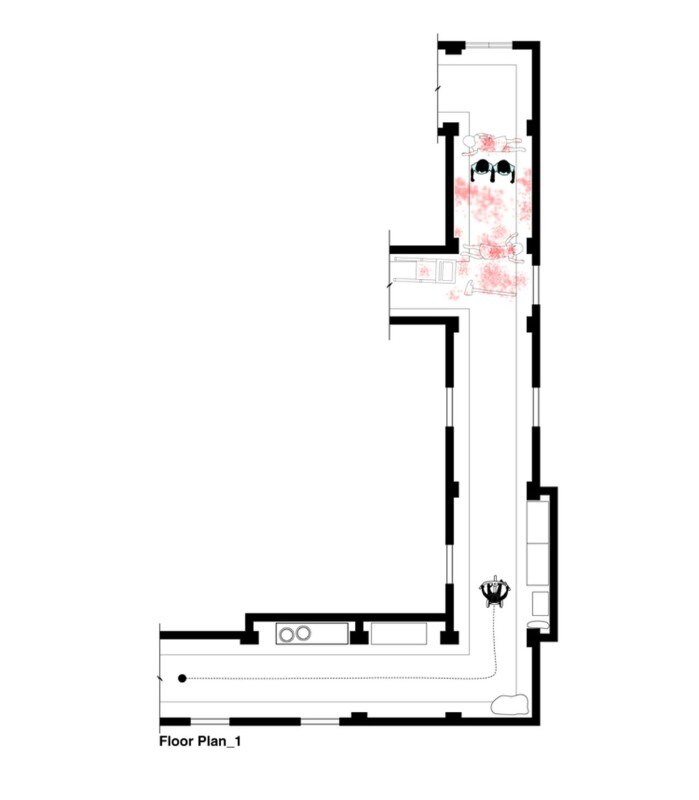

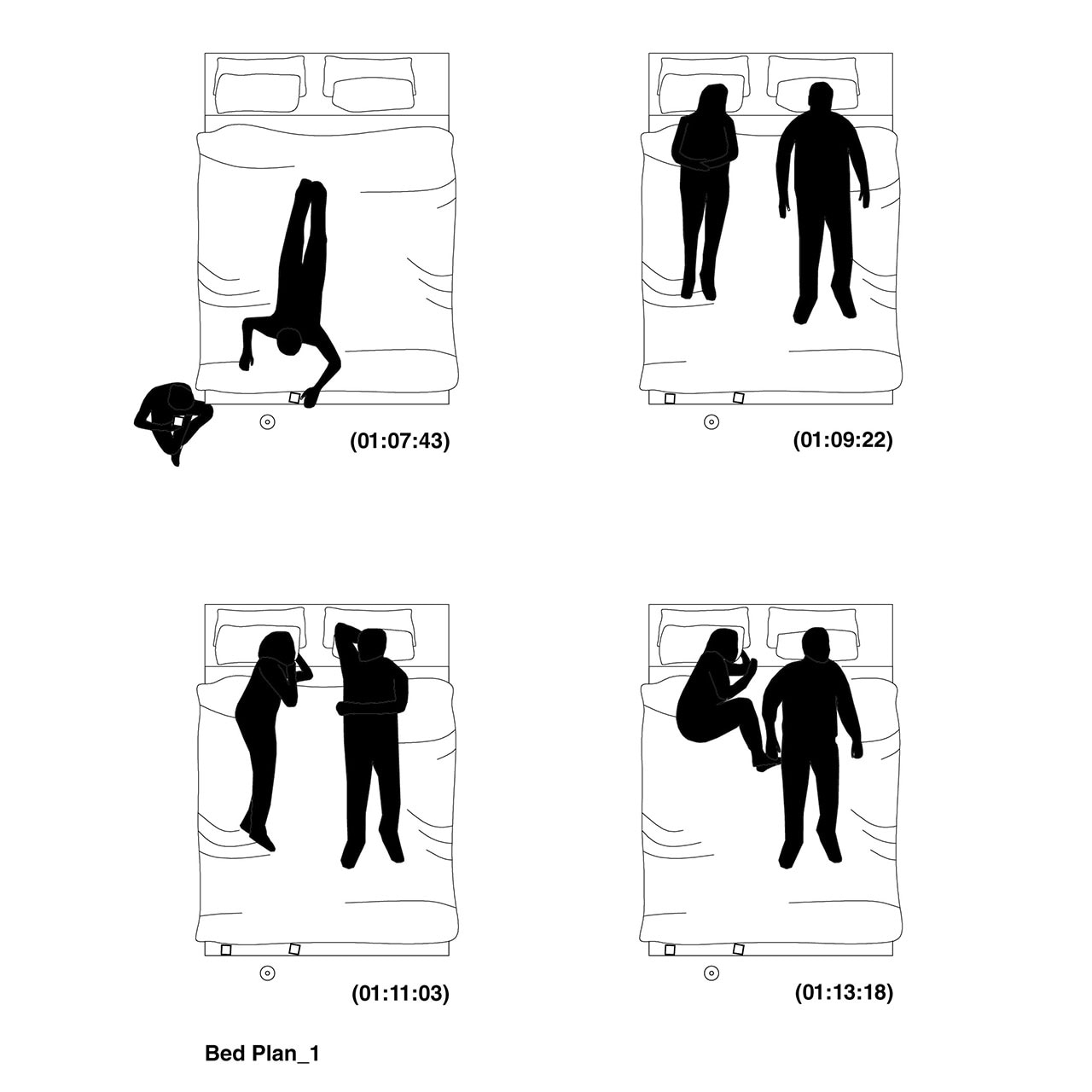

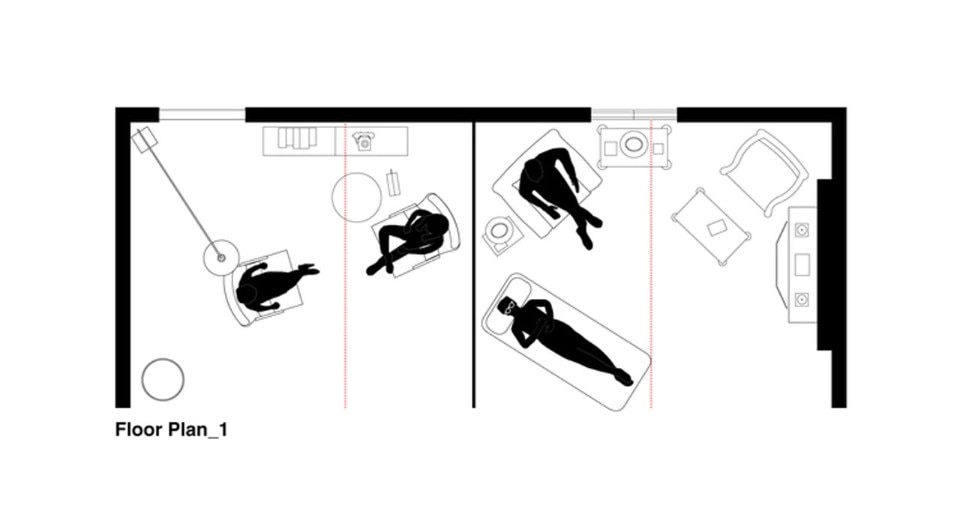

In creating Interiors, a digital magazine which, since 2012, has been examining the relationships between film, architecture and design, it is highly probably that the motivation that drove Mehruss Jon Aji and Armen Karaoghlianian was the very ambiguous nature of their interaction. How can one compensate for the partial representation that the medium of film provides, generally of a living space, particularly in the iconic cases of the most famous main scenes in the history of cinema? The result of a process of almost scientific reconstruction of the invisible, which has either ended up on the cutting room floor, or which was never even filmed. This is done in two ways: on the one hand by counting, for example, how many cameras were used, in what way and why; and on the other by graphically elaborating the plans that faithfully reproduce the entire set, whether it be real or papier-mâché, together with the characters and their movements, indicated with thin red lines.

View gallery

View gallery

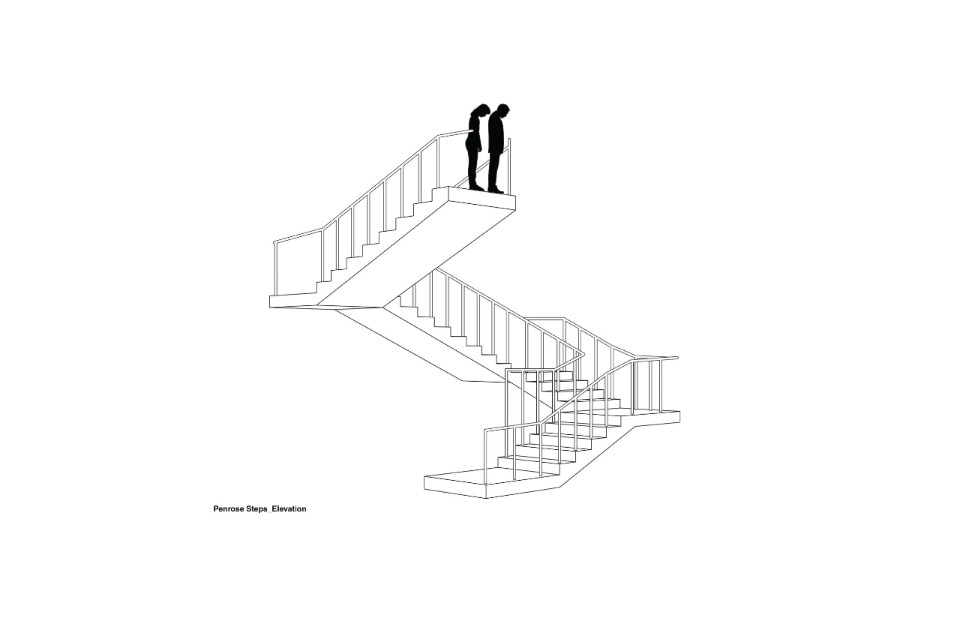

Inception_FINAL

In other words, no more secrets. Where once there was suggestion, now there is a translation. A detail which is anything but irrelevant, because if some may find this mass of critical thought excessive and anti-poetic, it means that they are not completely aware of how the fandom of cinema enthusiasts works. The very fact that Interiors is complete with a official store where one can buy the plans of Seven and Inception brings to mind what Carrie Fisher had said about the fanaticism surrounding her character in Star Wars, Leia. In her show entitled Wishful drinking, among the forms into which she has had the honour of being transformed over the years, the princess lists a bar of soap, a stamp, a sweet dispenser and even the enviable status of a poster girl for bipolar disorder in the textbook Abnormal Psychology. Interiors makes its contribution to this collection with a silhouette obtained with CAD, which depicts her as she reaches the other side of an interrupted walkway, clinging to Luke (Skywalker), on the Death Star.

View gallery

View gallery

The plan of this acrobatic scene from the first film in the saga, which can be purchased or printed from a computer, also forms part of the concept of memorabilia, but in contrast to industrial products, it is much more sophisticated, and carries with it all the explosive power of an X-File, the same power of the posters re-invented by the American Artist Adam Ryan Juresko, and his celebratory Girls on Tops, t-shirts with the names of superstars printed on a white background in Helvetica. Miraculous objects which offer, though their possession, together with the extra content that enriches the special editions of DVDs, an additional element contributing to one’s identifying with the mythological space in the film. This is particularly the case when, for example with Star Wars, the architecture has been almost entirely reconstructed in the studios. This is in stark contrast to taking a touristic tour to discover Pedro Almodóvar's Madrid, or to following the advice of Oscar Larussi in his Andare per i luoghi del cinema (visit cinema locations) (Il Mulino). It is never the same, however, as the experience that those locations create in the exclusive context of a film.

View gallery

View gallery

As Hitchcock said, “drama is life with the dull bits cut out”. Applied to architecture, this means observing buildings without urban distractions and human intrusion, unless they have been purposely choreographed, as in a film. In this respect, it would be interesting if, following classics such as the room from 2001: A Space Odissey, Interiors decided to study the dynamics of indifference and complicity which animate the adjacent rooms, separated by a bathroom, of Oliver and Elio in Luca Guadagnino’s Call me by your name, which was nominated for four Oscars. Considering that, due to the film’s success, this spring will probably see a boom in visits to that undefined “Somewhere in Northern Italy” that provides a location for the story, a plan of the second floor of Villa Albergoni in Moscazzano could provide a suitable alternative for those who are unable to go that far. For the future, instead, the modest proposal would be to insert plans in Playboy-centerfold style. In the end, the aim of Interiors is also to enrich the printed version. An architectural Cahiers du cinéma? Why not, there would be no lack of admirers.