Thirty years ago Arata Isozaki designed a house and artist's studio on a narrow alley lot less than 500 metres from the Pacific Ocean in Venice Beach, California. The slender structure was made for a friend of the architect's named Jerry Sohn, an LA art collector. It was later sold to musician Eric Clapton. To this day Isozaki's elegant house still manages to capture some of Southern California's idiosyncratic qualities, in particular the relationship of cultural activities (art, architecture and music for instance) to the natural landscape.

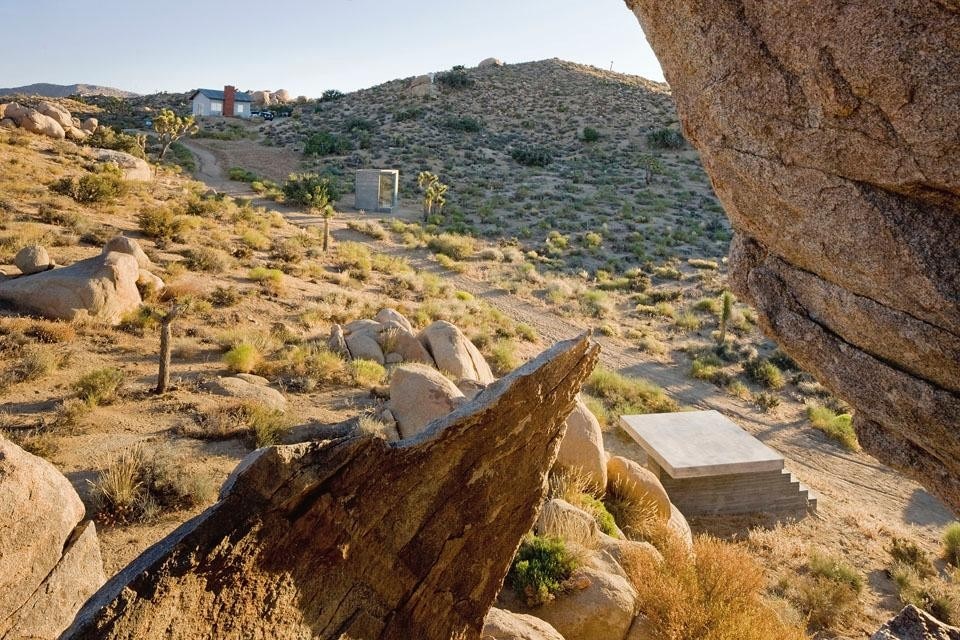

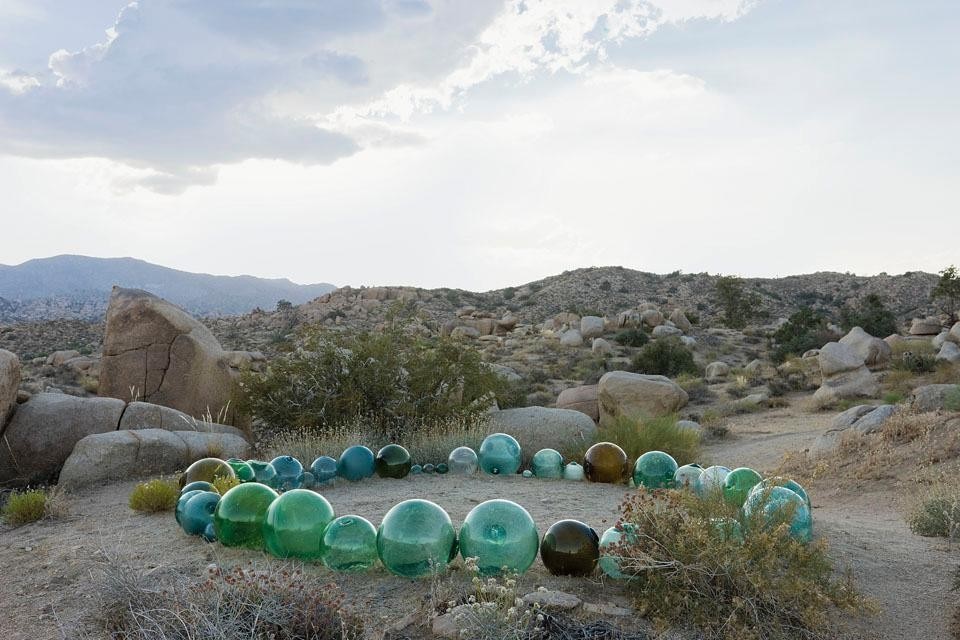

The client and architect stayed friends, exchanging correspondence over two decades and visiting each other intermittently in Japan or California. Years passed and Sohn came to acquire a property in the desert about two and a half hours southeast of Los Angeles. Surrounded by the benthic beauty of an ancient but now dry sea floor, dramatic rock formations, cactuses, reddish soil, Joshua trees and sagebrush, the property sits 1,500 metres above sea level in the High Mojave Desert. It is about 15 kilometres from Joshua Tree National Park and 50 kilometres northeast of Palm Springs, which is typically 5 to 7 degrees Celsius hotter on any given day than the high desert. During the day the temperatures in the Mojave can soar to 38 degrees Celsius, but drop at night to 1 or 2 degrees Celsius.

The primary sensation of being on the property is an impression of its remoteness, isolation, wildness and sublimity. Living on the site on a regular basis, as Sohn and his family do two or three times a month when not in LA, promotes a sort of deep hermeticism. Spending time wandering among the desert's quite large rock formations, across washed-out creek beds and over the site's mineralogical plains brings one quickly to an understanding of Southern Califonia's fragility. Despite the site's proximity to civilisation, one also gets a very immediate sense that our urban or cultural identities rest on the most tenuous of hypotheses supported by the most brittle of infrastructures.

Despite the site’s proximity to civilisation, one also gets a very immediate sense that our urban or cultural identities rest on the most tenuous of hypotheses supported by the most brittle of infrastructures.

Peter Zellner, Architect and professor at Southern California Institute of Architecture

Design collaborator: Yuko Oka

Structural engineering: Lindon Schultz (Summer, Spring/Autumn), Parker Resnick (Winter)

Building contractor: Jason Scharch and Moses Guzman

Construction supervision: Jerry Sohn

Art painted on concrete: Lawrence Weiner "OBSCURED HORIZON" (Spring/Autumn), Jeremy Dickinson "Nylint Truck" (Winter)

Client: Jerry and Eba Sohn