What induced the Europeans to mistrust the Bengali polymath was precisely what had enabled him to achieve those results: a different vision of the world. On the one hand was our Western outlook, which since the 17th century had proceeded by divisions and specialisations that greatly hindered any interaction between various disciplines. On the other, the conception of a substantial unity of the world, in which continuity, transformation and movement were the cornerstones of reality. Bose, who incidentally counted Henri Bergson among his supporters, had grown up in a culture that facilitated the idea of continuity between animate and inanimate. It was a short step from there to seek proof of that continuity. But, at that time, the shape of Western thinking would not even have allowed him to imagine anything of the sort. The Bengali scientist's studies would have to wait almost a century before anyone seriously expanded upon them. Only the move towards the idea of substantial unity in the real, accepted in the second half of the 20th century by official Western science, succeeded in creating the substratum that would allow research to move in that direction. Italy boasts one of the most advanced and acclaimed centres of these studies: the International Laboratory of Vegetal Neurobiology, directed by Stefano Mancuso in Florence. "LINV works on the hypothesis that the functioning of plants on a cellular level is not very different to that of animals. Life is a single thing; the differences between animal and vegetable are a human superstructure that has nothing to do with the reality of things. It was LINV that discovered a zone in the root which has a spontaneous electrical activity similar to that of neurology. A kind of 'brain' in plants, situated at the tip of their roots. Another line of research concerns sleep, which is linked to consciousness."

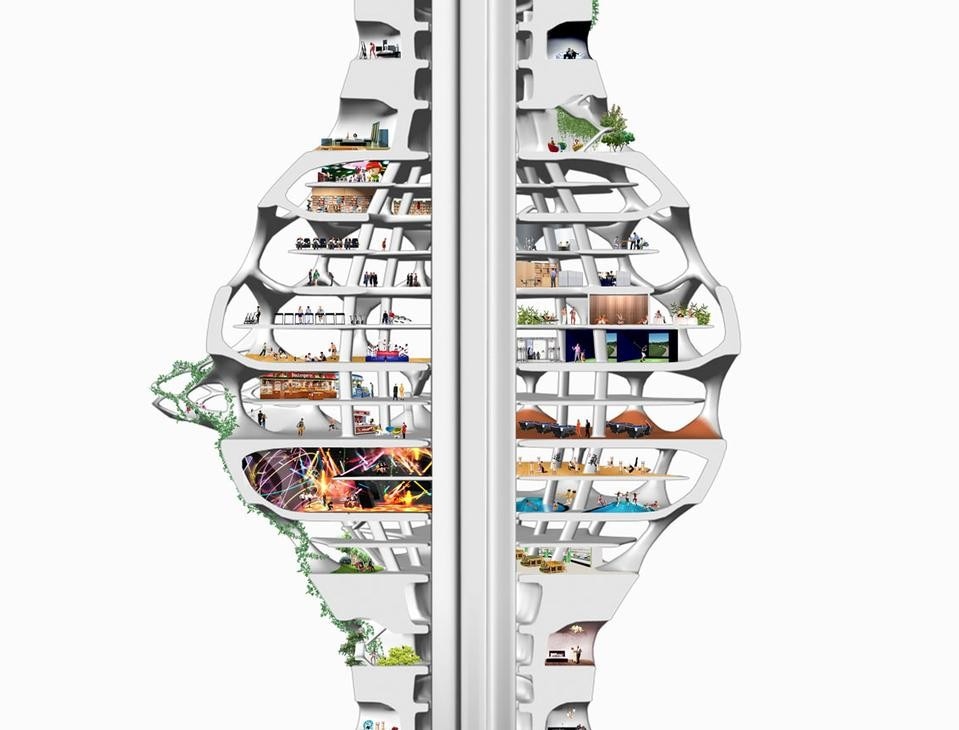

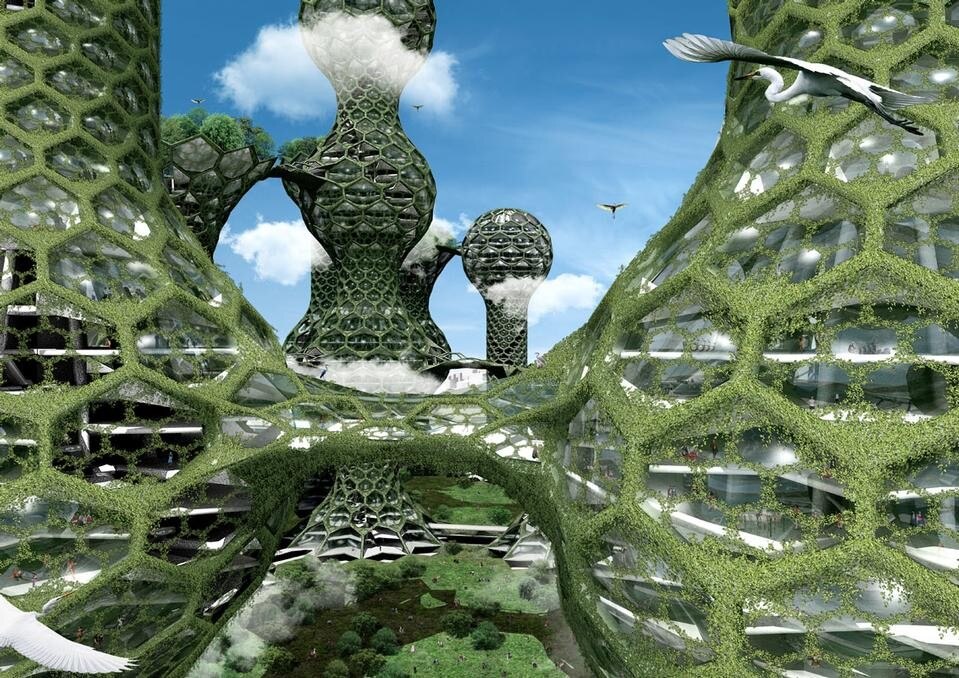

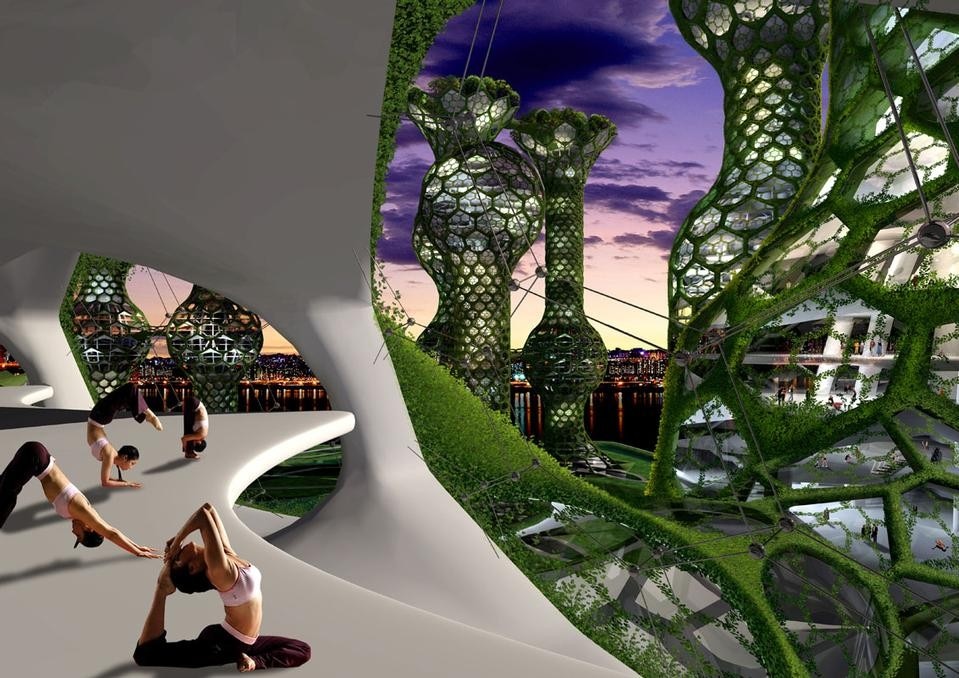

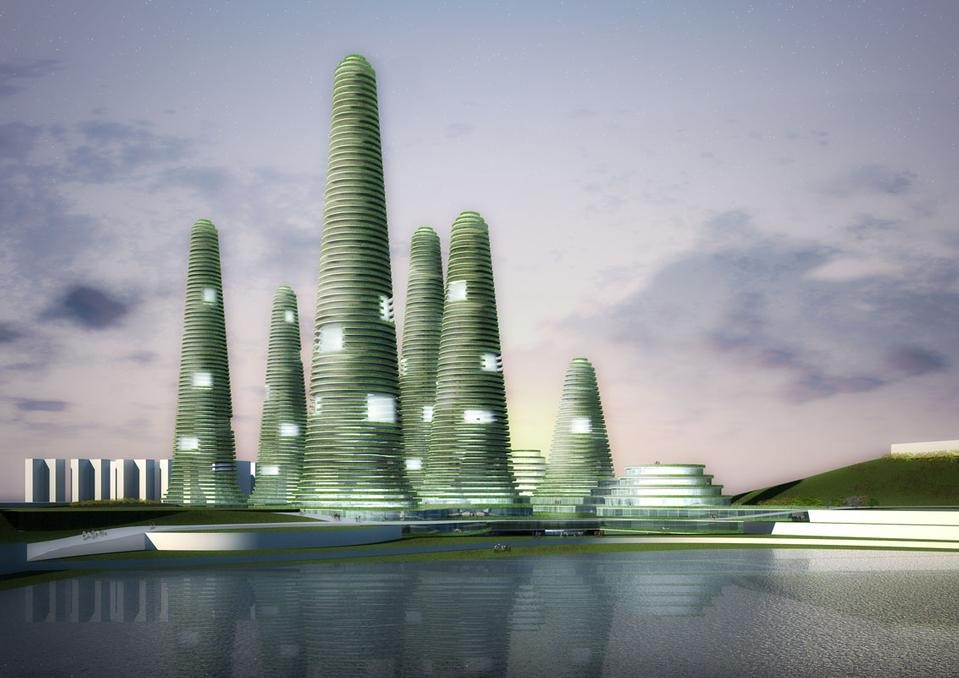

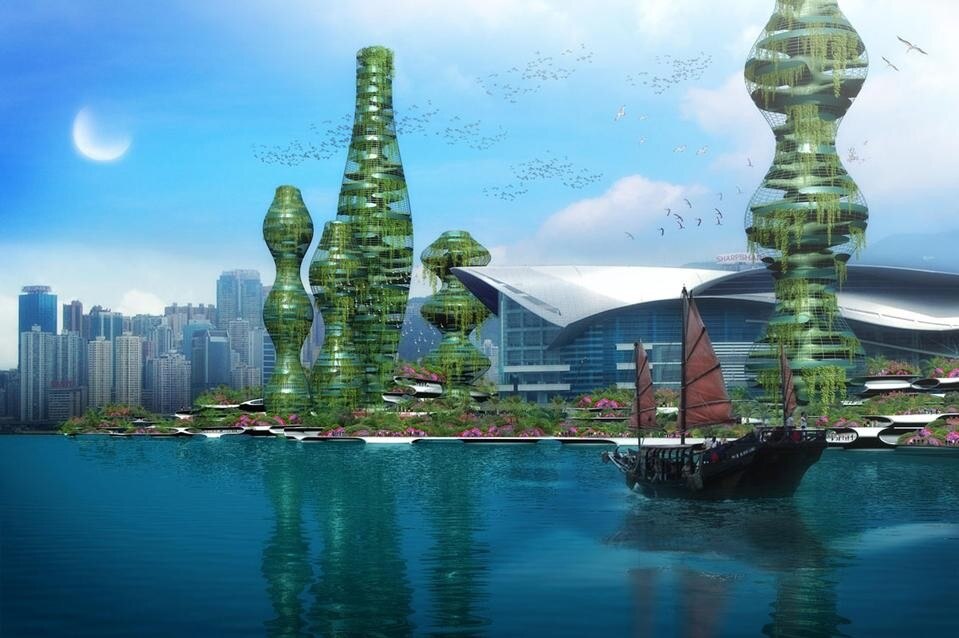

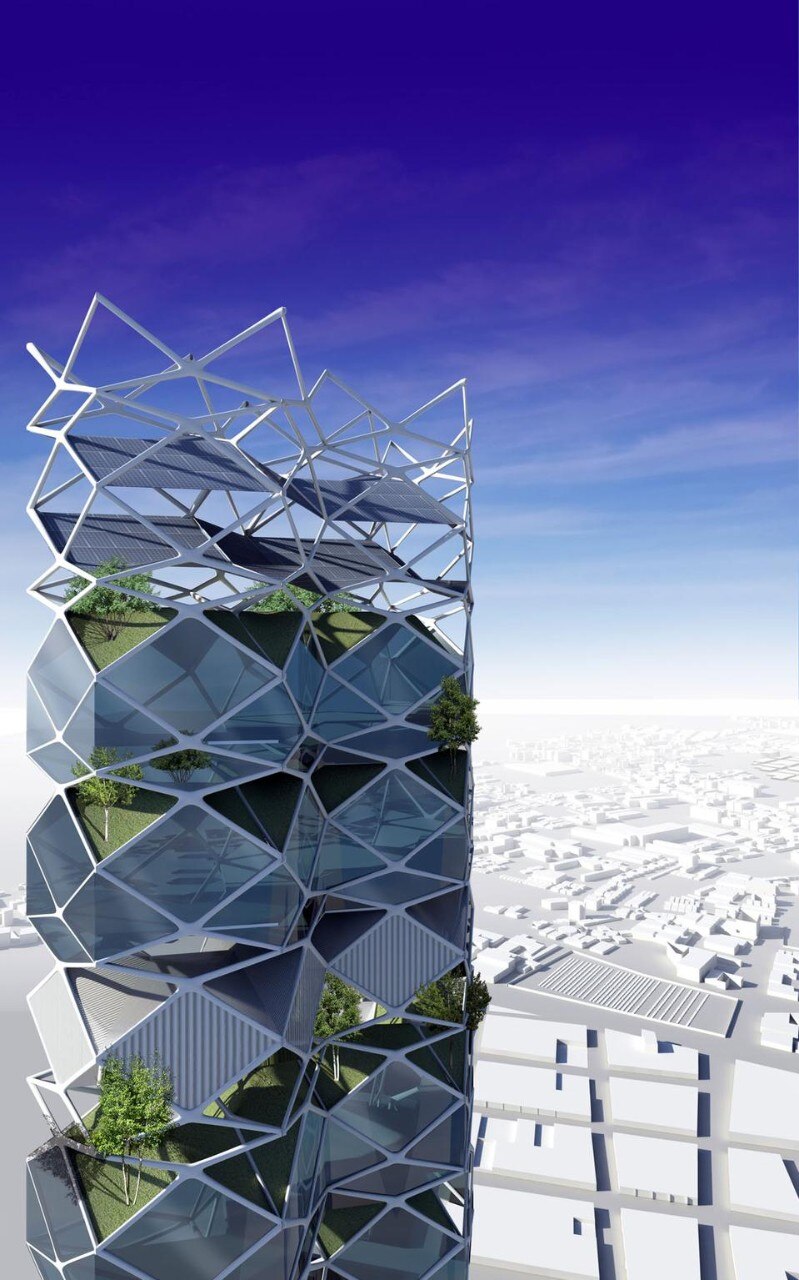

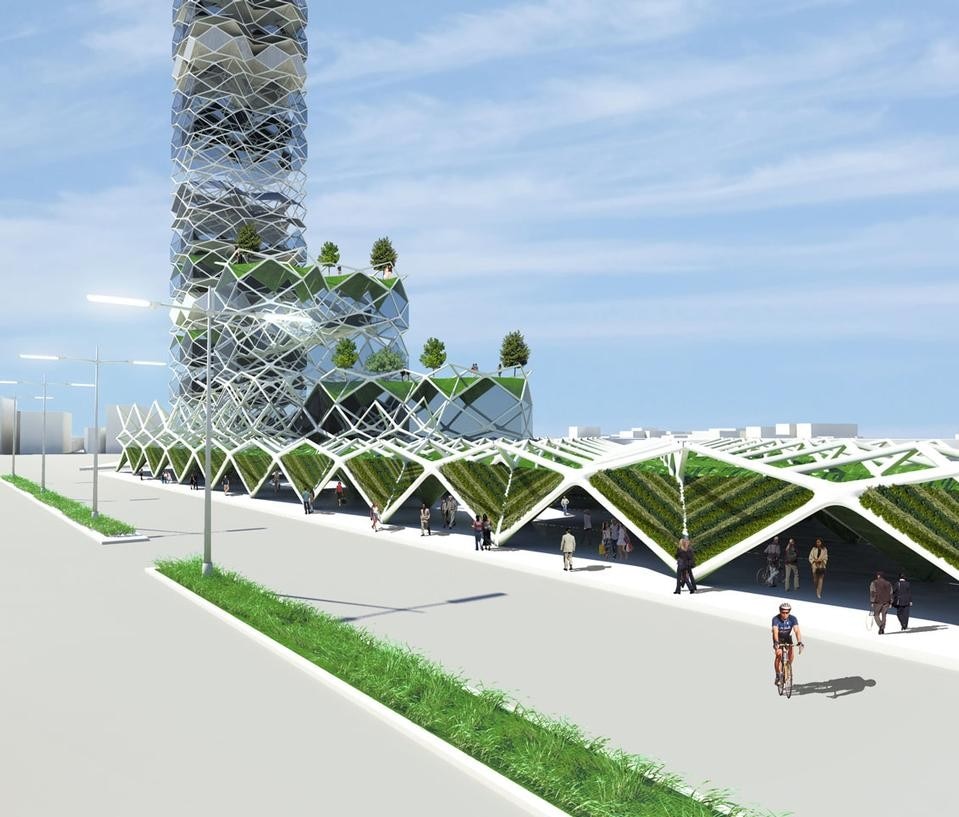

While making this concise selection of "green" architectures aimed at the future, I was immediately struck by the fact that many of the architects working on this theme are of Asian origin, in particular from Korea. One is inclined to think that the same system of thought that led Bose not to stop at disciplinary divisions is leading Far Eastern architects to make free use of plants in architecture. The designs by Kyungam, MAD, Mass Studies and Unsangdon clearly express a strong utopian force, almost a will to create new worlds. The French, on the other hand, have a different attitude. The work of François Roche takes up the great tradition that made France a model for those concerned with landscape and technical green space, while the futuristic and image-filled works of Vincent Callebaut reveal glimpses of a cinematographic visual culture. A more pragmatic spirit can be observed in the Italian project by Studio Iosa Ghini for a car park in Rome. Meanwhile it is no coincidence that the green towers by the Dutch studio MVRDV won a competition in Seoul, and that the British Grant Associates and Wilkinson Eyre Architects proposed technological gardens for the Bay of Singapore. Along with Dubai, the East is a training ground for new utopias, the true seat of architectural imagination in the early 21st century, where there is room for projects by large international groups like Studio Atkins.

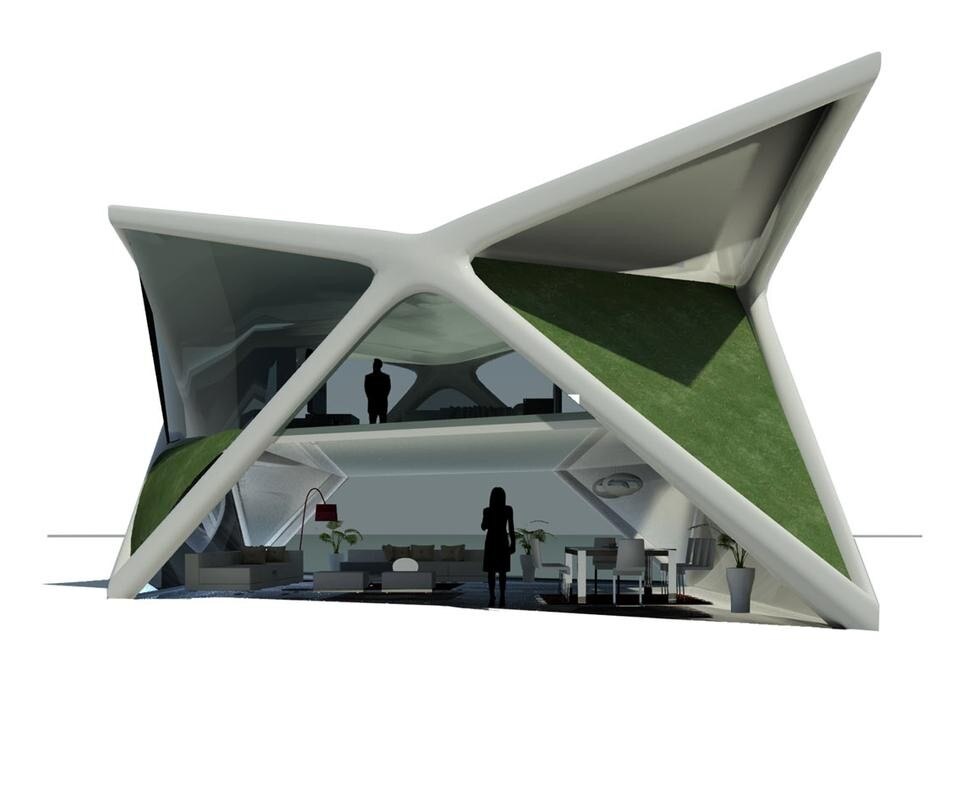

I know from personal experience how difficult it is to bring architecture, agriculture, botany and floriculture together. It is a task that calls for strong motivation. In the best of cases, the people concerned regard one another with mistrust, each clinging to the "conquests" of their own discipline, each with their own particular language. Here the same effort is required as that implicitly requested by Bose from the British scientists, namely to relinquish disciplinary borders in favour of a different conception of reality. Or, to narrow the field of action, of the space inhabited by man, where there is no longer a contrast between nature and architecture. In this idea of place, vegetal life can once again be what is has been for us humans for more than nine tenths of our existence on Earth: our real environment, and as such, the one that best satisfies our needs.

A key theme in recent years has been the development of urban cultivations. Here we see the chain farms of the Canadian Scott Romses, the French Atelier Soa and the Italians Studiomobile, manifestly indebted to the atmospheres of Flash Gordon. Human dependence on the vegetal element becomes evident. And so does the much less obvious relation between agriculture and architecture, two hitherto sharply contrasting spheres which today instead can intersect and join hands. For that matter we need only dig a little into the mythological origins of both to discover a substantial unity between them. Just as in the foundation of every human space, be it a city or a building, "agriculture was originally perceived as a violent act, in that man, by practising it, raped nature, his mother, and dominated it; which is the opposite of what happened with horticulture, an intimate, peaceful and positively symbiotic collaboration with the earth-feeder."