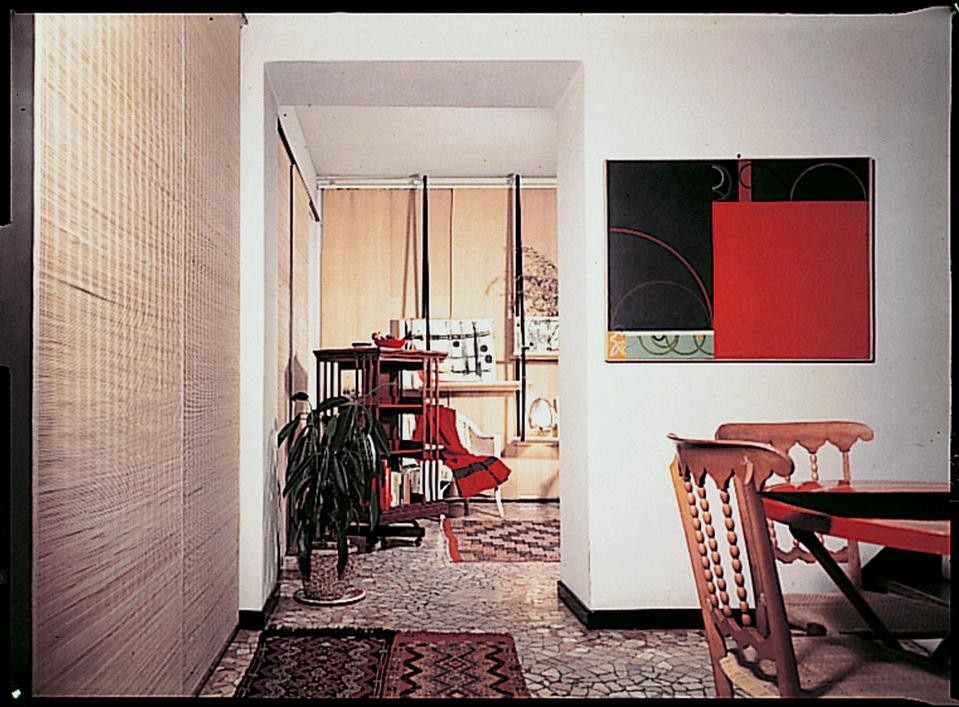

The rooms are faced with Madagascar panama canvases running on rails, which conceal wall spaces containing shelves, a mobile bar and a cupboard. The floors are covered with Montenegro carpets and mats. The numerous paintings are by Capogrossi, Calder, Sambonet, Max Bill, Munari, Léger, Le Corbusier. In the square entry space, Rogers brings together a bookcase with layered birch tray shelves hung from black hemp strips, a small English period bookcase in tropical rosewood on wheels, and two garden chairs painted white.

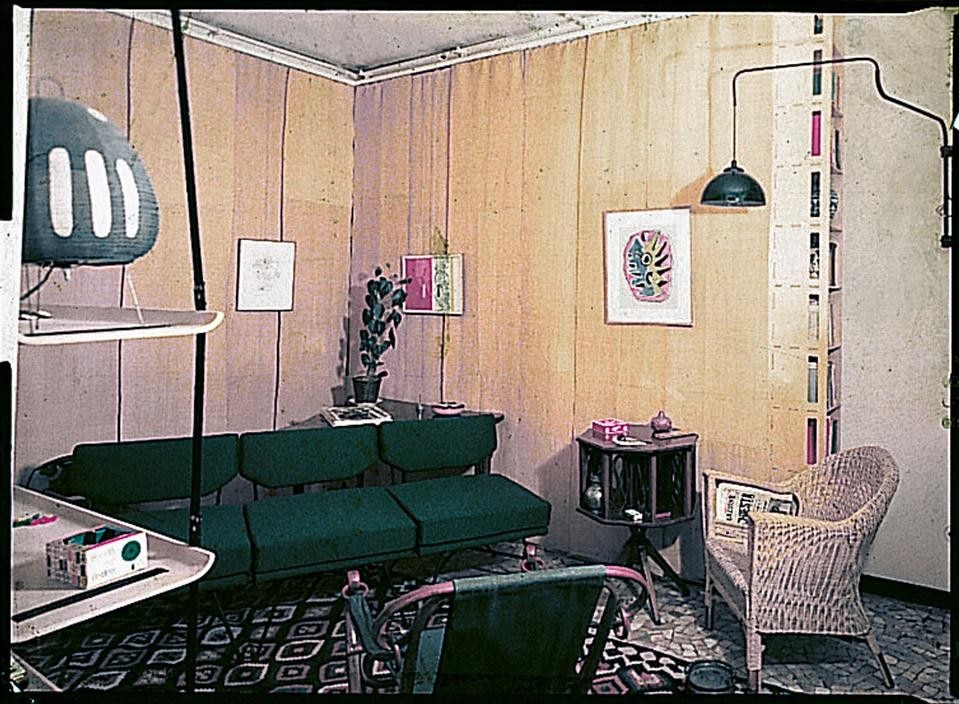

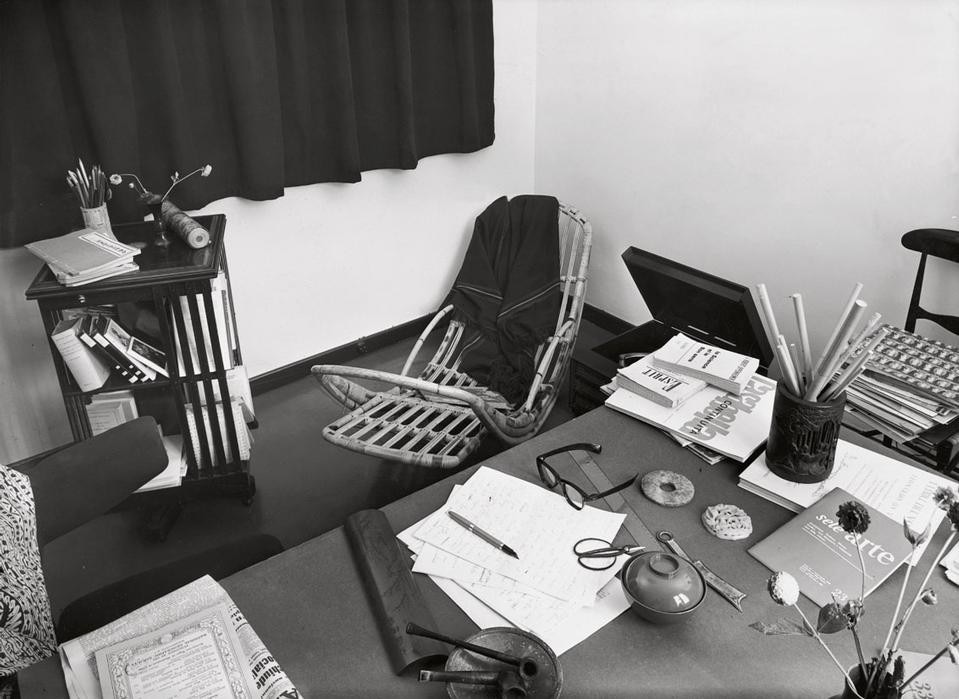

In the room after the dining room, four Chiavari chairs are placed around a lacquered metal garden table. A rail-hung sliding bookcase alternately screened on either side by ash slats can close off the view between this area and the next, which is the living room. Housed in the bookcase are paintings and ceramics from Peru, Greece, Mexico and Brazil. A large Qing dynasty painting hangs from the ceiling of the third room. Below it is a sofa designed by BPR for Arflex, composed of three independent seats, and a Viennese late- 19th-century armchair. Wicker chairs made by Castano are in the studio – with the rocking chair altered by Rogers – and in the living room, with an internal magazine-pocket.

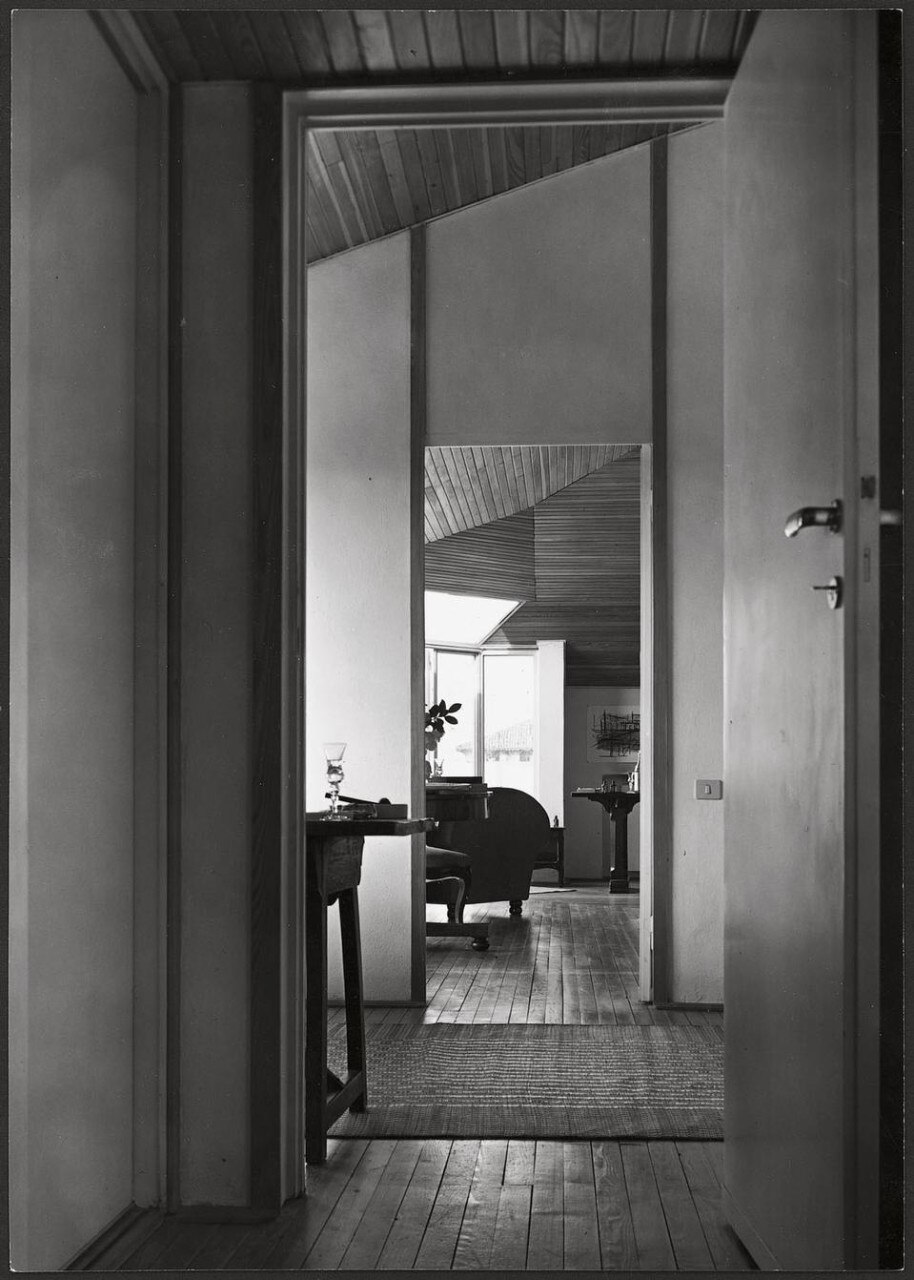

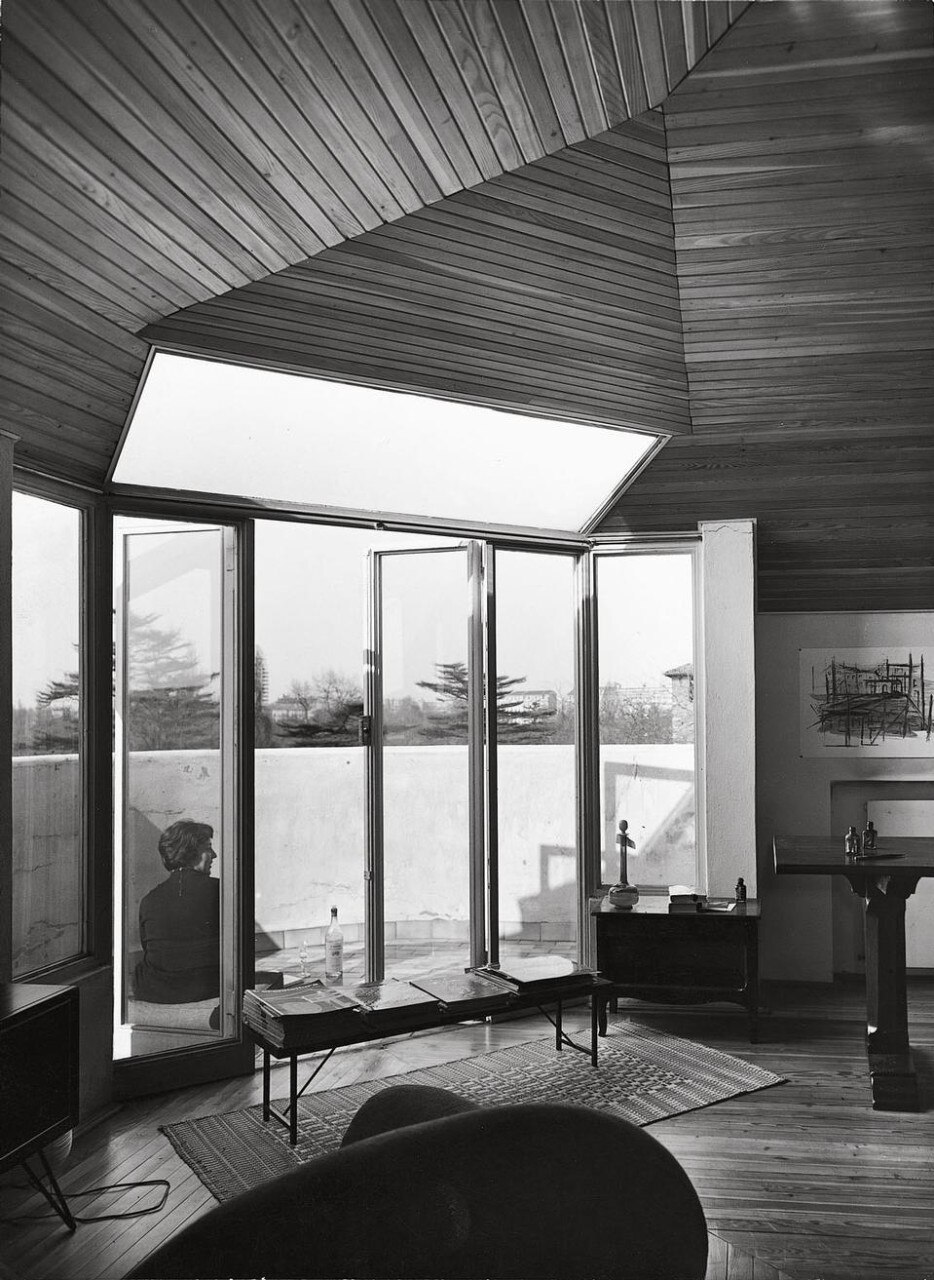

The personally designed furniture consists of a few simple pieces, custom-made for the architect by Piero Frigerio of Cantù. The house is created mainly from objects of no particular economic value, bought on Rogers’s numerous travels throughout the world or in antique shops. They represent the owner’s life and sentiments. The small bachelor flat in a corner attic with a view of Milan’s Sforzesco Castle is different, created from a young architect’s design. The flat is in Via Jacini and the architect is Marco Zanuso, who in 1955 was appointed by a certain Mr Olivetti – “a person living there alone and periodically” – to organise a row of rooms opening extensively onto a panoramic terrace.

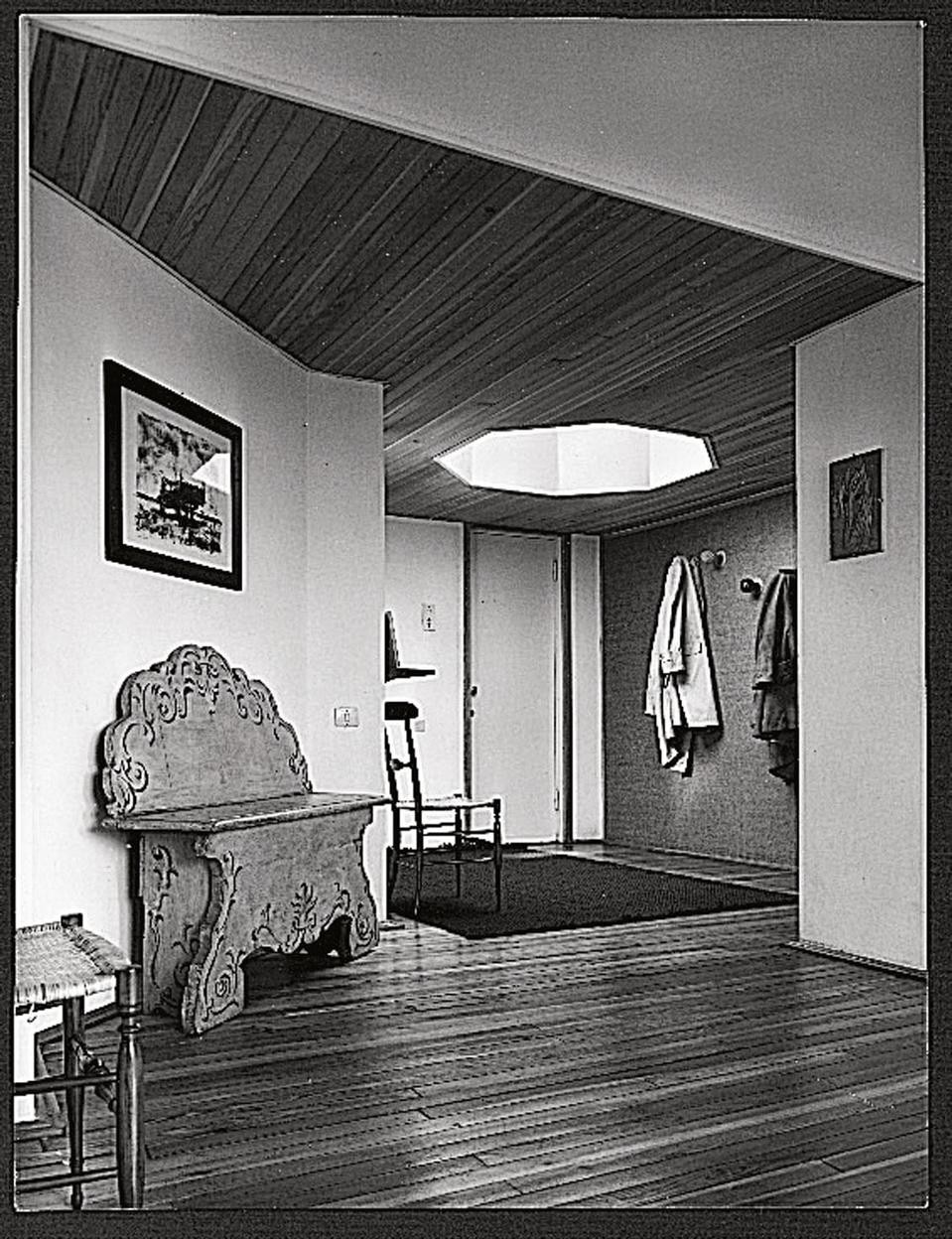

Although this is one of his earliest private interiors, in Zanuso’s work the clear design of volumes and spaces is distinctly recognisable, with its continuous movement of white plaster walls between equal floors and ceilings in pitch-pine boards. The ceiling bends with the light, in the spacious aperture of the dining room-studio facing the terrace and in the octagonal drum skylight over the entrance. The occasional furniture and objects furnishing the attic were chosen by the client.

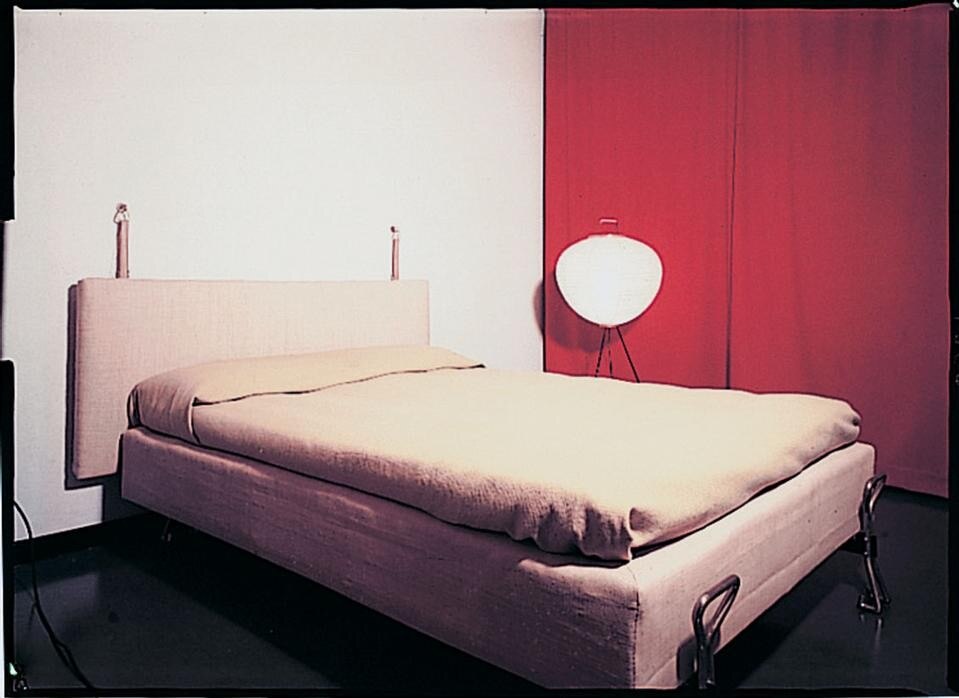

The “house for a bachelor” designed by Giulio Minoletti in Varenna sticks out like a shelf from the embankment wall to skim over the lake. Inhabited by an active owner in a bathrobe, it may be considered the prototype of this new postwar type of building, which in numerous examples proposes smaller and more flexible spaces (in Varenna three juxtaposed beds forming an immense sofa) furnished in a practical way but without sacrificing the elegance of new materials and the presence of a young lady surprised by a photographer: a reminder perhaps that bachelorhood is not always an irreversible status.