Embryonic Memories of Floating

Akira Suzuki

Strange as it might sound, I’m tempted to draw comparisons between the Matsumoto Performing Arts Centre, the first real theatre project by Toyo Ito, and his early (typically regarded as his “debut”) residential work. Yet on the opening night of the opera performance, as I expectantly ascended the grand stairs and felt myself swept into the foyer, the gently curved walls reminded me of the spatial experience from Ito's White U (House in Nakano Honcho) thirty years before. As the curtain came down in the Grand Hall (or more precisely, a wall of recycled PET bottles designed by Tadao Ando), and the audience still full of excitement from the performance mingled out into the foyer, I found myself back on the grand stairs, only this time descending. What on entering had seemed a wall speckled with translucent patches of sunset was now by night a white expanse bathed in white light from below. The main entrance opens right onto the grand staircase and then leads to the foyer. The traditional opera house approach, as interpreted by Ito, becomes one fluid continuum: people need only go with the flow.

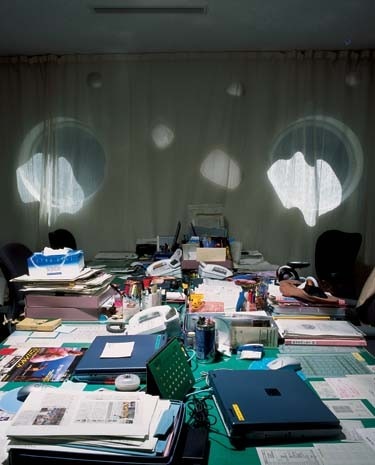

Matsumoto Performing Arts Centre stands on the site of the old Civic Culture Hall in the heart of the city, some fifteen minutes from Matsumoto Station. The main façade overlooks a residential area; the adjacent Shinto shrine adds a note of greenery to the site. Ito's competition proposal responded to the stringent environmental conditions almost magically through the spatial composition on plan. By situating the fly-tower in the middle of the building and reversing the stage and the audience seating, deliveries can be handled more efficiently while significantly reducing the volume of truck noise for the surrounding community. Likewise, the curvature of the building's exterior wall is skirted by the seating of the Grand Hall with its horseshoe-shaped balconies and enclosing ring of dressing rooms. That said, the basic skeleton of the plan consists in its entry-stair-foyer flow, a baroque spatial scheme that serves to heighten the “drama of entrance” in adrenaline-coursing curves. The Ito proposal has the audience enter to the left and proceed around the back of the space. But to simply hear the dynamics and functionality explained is nothing compared to experiencing it firsthand. Better to picture the plan as an embryo in the womb. (Such a shape is even used in the Centre’s logo3. In Japan, opera house spaces - our National Theatres included - are also required to function virtually simultaneously as music halls and small theatres. The Matsumoto Performing Arts Centre has a traditional European-scale opera hall space with four tiers of balconies, though a unique lowering feature in the ceiling helps “contract” the space so as to accommodate smaller productions both in terms of acoustics and audience capacity. Moreover, the “four-square stage” plan4 allows the back of the stage to be transformed into an Experimental Theatre, complete with folding banked seating. It is doubtful that those entering from the so-called “Theatre Park” lobby will even realise that they are backstage at the opera. The embryo-shaped space that connects and envelops both theatres is also a flat slab-built “tabula rasa” raised on slender round columns. In marked contrast to such intense spaces as the Grand and Small Halls with their perfect acoustics, consummate lighting and air conditioning, this space completely lacks architectural metaphors or programmes. It is designed to let viewers, actors, performers and directors alike float in an undefined environment - although it conceals the possibility of some creative production suddenly turning the place into a theatre space for a single night. Ito has said, “I want to create flat spaces free of hierarchies.”5 Certainly ever since Modernism, building interiors and exteriors have been coupled via transparent facades, and now today's technologies have dispersed machines and equipment throughout the living environment. On the other hand, we flesh-and-blood humans paradoxically remain as misfits in these featureless spaces. This leaves people little option but to act fashionable and render our physical form into mere shadows or transparent digital data ghosts scattered indistinguishably into these spaces.

Critic-photographer Koji Taki's camera once discovered dynamic changes latent in the otherwise seemingly static planar continuum of the White U interior as he followed around the owner's rambunctious daughters. I relived the same experience of discovery walking the white foyer of the Matsumoto Performing Arts Centre. There were the womb-like curved walls and the soft light that seemed to recall embryonic memories of floating in amniotic fluid. It is a space just waiting to be brought to life. The long walk up the foyer finally brings me to the theatre door. It opens into an explosion of deep red light6. Surely I'm not the only one who imagines some heavy performance bleeding out into the pristine white foyer in the not-so-distant future.

Kazuyoshi Kushida, director of Matsumoto Performing Arts Centre, and Toyo Ito, architect, in conversation

Scouting places

One of the distinguishing features of this building is that it's a collaboration between stage director-actor Kazuyoshi Kushida and architect Toyo Ito. You've been working together on this building for a year and a half. What are your feelings about the project now?

Kushida There are those among the theatrical designers who are solely concerned with the space and equipment of a theatre. But me as an actor, I've always kept thinking further. What sort of stage equipment and fittings should there be for actors? How should we face the audience? What would make the ideal space for staging theatre? Everything somehow relates. Since becoming Director of Matsumoto Centre for Performing Arts I've had a real opportunity to reassess my very strong concerns about theatre spaces. But I suppose it was always this way. When a travelling entertainer or troupe came to a town, the first thing they'd do is scout for a place to perform. "How about under that big tree? People'll come in droves." "No level ground there, we'll have to make use of the slope somehow." They had to make creative adjustments as each particular place demanded. As an actor, I've always felt a fundamental connection with "scouting the right place" and "getting a crowd." So last winter, before deciding whether or not to take this job as Centre Director, I secretly came and had a look at the site. This was during the snowy season.

Ito It was exactly one year before completion. The steel framework was already largely up…

Kushida Right. The concrete moulds were in place. It was a big, dark mass. Quite moving, it really grabbed me.

Whereas up to then you'd always gone out scouting for places, here the place came and found you. By the time you became Director and first met with Ito-san, the basic plan for the building was done. What was your first impression of the facility as designed? Granted, there were probably both good and bad aspects…

Kushida I remember thinking, if only the construction could be made softer, a little more flexible. Which, of course, had a lot to do with my ideas of "flexibility" up to then. Meaning, for instance, I'd been thinking it would be good to give the theatres the possibility of removing all the seats. So when I saw the plans, it was "Oh, they're fixed" or "If only we could move the seats into a semi-circle." I even talked over several points with Ito-san, "Is it so impossible?" "Can't this be changed at this point?"

Ito Particularly about the Small Theatre. But by the time you (Mr. Kushida) came on as Director, the plans were completely done and at a stage where they were already unchangeable. There were definite limits on what could be altered. Just now, you mentioned the idea of "scouting places." Well, the same was true of architecture in ancient times. In the books of Vitruvius or Palladio’s four books on architecture, we read that the first task of the architect was to search for a good site. But in our day and age, there's no call for that any more. It's all we can do to tackle the plot of land we're given. So probably the difference between your work and mine is, even given a good site, my making something there one time only is "architecture." Architecture in ancient Japan was once a continual, on-going process, whereas architecture today is an extremely artificial one-time-only separation from the environment. This is rather hard work for me. I myself wish I could work on a more continual basis.

Inroads into the building

Ito Theatres today are hemmed in by all sorts of functional constraints. They have to be absolutely soundproofed to the outside, the acoustics will have to be even throughout, there are general restrictions on lighting and whatever, all of which tends to make any theatre built anywhere more or less the same. That and people—local authorities included—have these fixed ideas that “a theatre must be like this,” even more than for libraries or museums, and the architect faces major opposition should he try to break away from that. If you had come just a little sooner, I would have liked to have you unravel some of those knots. Regrettable.

But it’s remarkable that in the case of Matsumoto, Mr. Kushida's own background in theatre made him take a more active "can-do" approach as director.

Kushida I'm amazed they chose someone who doesn't wear a tie! (laughs)

Ito No really, at the symposium here the other day, you got up on stage and started moving around, talking flat out, then suddenly exited to the Foyer - and that was the Director's speech (laughs).

You alone have done the work of three, which has been a real boon to me.

Kushida Well, more and more people are beginning to understand, though I must say I'm relieved they accept what I do.

Ito When you walk through the Foyer, it becomes a theatre. We've all been brought up on the idea of theatres in all confinement, but your presence has thrown that wide open. I'd pressured myself into thinking I had to concentrate on improving the various features of the Small Theatre, but when you get 200, 300 people in there watching a play, when you see the curtain call, it becomes a small city—an urban space. Just like when you walked right outside to the Foyer as soon as he’d finished, you get the sense that roads run right through the building, that people bring in their own continuity. That's the most exciting thing for me.

Kushida Now from the completed building, I got the sense that anything's possible, that we can do whatever we want, the discovery that stopping somewhere, anywhere, and just speaking forth can be a theatre. It can expand far beyond from the physical building, it can reach all the way out into the street. We can say, "The performance continues outside," or "Act 2 is on the roof." All sorts of things become possible.

The entire building as urban space

With your Free Theatre in Roppongi, right in middle of Tokyo, you entered a whole other dimension, which seems to have played on the differences between the city and the theatre space. Whereas with Matsumoto, you seem to say this is a theatrical space within a city and this space contains another theatrical space within. The setting seems to be a little different.

Kushida Those days and today are different times. The whole atmosphere around theatre has changed. In the 1960s and 1970s, great significance was placed on "intervention," on how you could thrust into the city and make your own base there for creating a theatrical space; while even if I did the very same things today at my age and position, it would only be an act of authority. Conversely, I have no idea whether today's young people could make a go of trying the same tactics. Times have changed. Though I do feel there's more freedom now to try different things.

In Matsumoto, you seem to be principally looking at how to stage this entire public space with its three theatres as a whole, at how people can have what kind of experience where.

Kushida Correct, and I'd like our presence here to have an influence on other cities throughout Japan. That's extremely important. I'd want us to provide a model, to say look, here’s how making a facility like this - and not in Tokyo, but in a provincial city - can change people and things.

Ito You told me you wanted to hold a festival of street performers there. It's a great idea, something I really look forward to seeing. Performers right there on the escalators, in the Foyer, on the roof, spilling out of the entrance. This would make everything an urban space, everything a street. I never could have won this competition without perfecting the performance of the Grand and Small Halls. But this also led me to want to design the space leading to the two theatres in an interesting way, to make it all a sequential "theatre." I actually walked around the Foyer over and over again at the opening, just to see. The sensation was that of people moving about naturally.

Kushida And glazing the far back of the stage area was a fantastic idea!

Ito The rear of the stage faces onto the Foyer, a reverse on the typical layout. Opening that up allowed a view of the entire Grand Hall, as well as of the Experimental Theatre, from the Foyer. I wanted to take the horseshoe-shaped, somewhat stuffy traditional Western opera-style Grand Hall, and add on a little something to say, "Wait, that's not all there is to theatre." Presto, we had an Experimental Theatre. I think that was our saving grace.

Enjoying architecture

Ito Some people might wonder what I mean when I say I want to "enjoy architecture." Well, when Modernist architecture first appeared at the start of the twentieth century, almost a hundred years ago, it arrived under the ideological banner of social change, but now only the dogma survives. That, to me, is the worst thing about architecture. An utter bore. More and more recently, especially since Sendai, I find myself thinking about how architecture can break out of that straitjacket. There's a logic that prevails only in architecture, which argues that if one builds according to this logic, then it will make the users happier and more fulfilled—however, it totally misses the mark. Is this really more enjoyable? It seems to me we could frame a new notion of architecture on that basis. I think that would be the most radical move. That's the sort of architectural thinking I want to be involved in creating.

Kushida You said you wished we'd met earlier. Well, that's exactly the sort of thing I’ve wanted to discuss with an architect.

Ito We don't want to be driven along some linear rail. True creation is when you can't tell what's ahead, you can't see until you get there. If that leads to continual on-going exploration—that would be the most interesting thing. How can we establish a methodology from that? That's the key to whether or not we can create a new architecture.