The first, modestly scaled Catholic cathedral of Los Angeles was built in the 1870s, when L.A. was a dusty farming town of 50,000 people. In 1904, as immigrants flooded in, the diocese resolved to build a new cathedral, but the decision was repeatedly postponed until the 1994 earthquake rocked Saint Vibiana’s and made it unusable. Two years later, developer Ira Yellin and architect-planner Richard Weinstein organized an international competition to select an architect. Rafael Moneo was named the winner on the same day that he came to L.A. to accept the Pritzker Prize. The archbishop of Los Angeles, Cardinal Mahony, wanted to build over the humble old structure; however, preservationists objected, and a new, more prominent site was found. The new cathedral occupies a full city block atop Bunker Hill, just west of the original settlement and City Hall.

In contrast to the Music Center (an overwhelmingly banal arts acropolis completed in 1969), which lies diagonally across the street intersection, the cathedral is asymmetrical in form and placement on its rectangular site, and its plaza is designed to serve as a civic amenity as well as accommodate festive processions and outdoor services. An outdoor café, olive grove, fountains, gardens and shade trees soften the expanse of scored or stamped concrete. The complex is contained yet readily accessible. Lita Albuquerque’s fountain (a film of water flowing over a white marble drum) and cascade mark the point of entry from the underground parking garage into a sunken plaza and through an arch topped with a carillon from the street. From this open-air foyer, diverging flights of steps and a ramp lead up to the north entrance and main plaza.

A pergola and double-glazed windows (etched with angels) separate the plaza from the river of cars churning along the Hollywood Freeway to the north (Moneo likens it to the Seine flowing past Notre-Dame). Moneo, whose previous experience of designing sacred spaces had been limited to a small chapel in Spain, understood the challenge of creating an architecturally distinguished building for a strong-willed client and a multicultural archdiocese of four million. ‘Conscious of the difficulty that the construction of the cathedral implied, I did not covet the commission, but fate ended up giving it to me’, he later wrote.

The National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., and Saint John the Divine in Manhattan have been handcrafted over generations, like their Gothic predecessors. In L.A., a limited budget and an urgent need for new space mandated completion in less than four years. However, the cardinal wanted the cathedral to endure for at least five centuries. To this end, the structure is mounted on 200 base isolators, which should cushion the impact of the strongest earthquake, and the concrete mix was carefully calculated to achieve maximum density, impermeability and evenly integrated colour.

There’s a suggestion of adobe in the warm-toned concrete, and the cloisters and deep-set windows recall the Spanish missions. But the stepped profile of the walls, which fold and jut at eccentric angles, avoids literal allusions to history. The blocky forms are an understated expression of the interior volumes. The cathedral may be entered though massive bronze doors to the south or a more modest entry to the north, down ambulatories lined with wedge-shaped chapels that face outward to separate private devotion from public worship. The south ambulatory slopes gently up and is tapered to create a forced perspective, and light from a narrow slit in the ceiling gleams off a floor of polished limestone blocks. A baroque Spanish retablo mounted on the west wall draws the eye. To attend mass one can follow this processional route to the end, turn into the nave and descend toward the altar or pass directly inside through openings between the top-lit chapels.

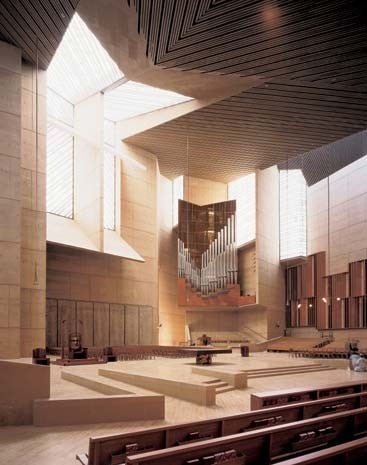

For inspiration, Moneo turned to Le Corbusier’s chapel at Ronchamp and Erik Bryggman’s Resurrection Chapel in Turku, Finland – two of the very few buildings he considers to be both modern and spiritual in feeling. However, these places of worship serve small groups of pilgrims or mourners; the cathedral accommodates 3,000 and is open to all. ‘What they all share’, the architect observes, ‘is light as the protagonist of a space that tries to recover the sense of the “transcendent” and is the vehicle through which we are able to experience what we call sacred’.

Most of the glass in the cathedral is masked by screens of veined Spanish alabaster that create a soft glow more reminiscent of a Byzantine than a Western church, though a few fugitive sunbeams glance through the unshielded light scoops over the transepts. Within the spacious volume of the nave, the folded planes and interwoven geometries of walls, paving, slatted ceiling and alabaster provide an inspirational experience. Shallow transepts and a vestigial apse hint at a cruciform plan, but the celebration of mass is centralized by setting the altar at the front of the sanctuary and allowing space and seating to flow around it. The side chapels create an insistent vertical rhythm, and an axial path links the baptistery to the altar – a vast slab of dark-red Turkish marble. The impact of this glorious room would be enhanced if the thicket of lamps suspended above the pews were rigorously pruned – or eliminated in favour of the recessed ceiling spots that light the sanctuary. The bronze trumpets that amplify sound are less obtrusive than suspended speakers, but again they are too prolific.

Still more distracting are the commissioned ‘artworks’ that will eventually fill nearly every space and surface. The pioneers of modernism banished surface ornament, but the general public still finds bare spaces ‘unfriendly’ and insists on cluttering them. When Moneo expressed the wish that the art could have been more daring, the cardinal responded: ‘We have MOCA down the street – let them do the contemporary art. We have so many ethnic groups; we want them to feel at home and recognize basic things’. This translates into figurative forms – a sculptured angel over the door, a tapestry of saints, a wreath of gold angels around the base of the altar – that are saccharine and curiously lacking in conviction. The stained-glass windows of a medieval church told biblical stories to illiterate churchgoers, and the artists who designed them believed in what they were doing. But the L.A. cathedral’s parade of saints – modelled on people plucked from the streets by a casting director – panders to the everyday and mirrors its viewers like a television sitcom. The artist, Gregory Nava, has commented: ‘The figurative artists I admire take a pessimistic view. This had to be entirely hopeful and life affirming. It’s tricky to do that without Disney-fying the art or making it sentimental’. Still to come is a mural recounting the history of Christianity in Southern California that will cover the south ambulatory wall. It is not a happy prospect.