When Bhutan's King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck decides to envision his country's future, he starts not with a capital city in need of renovation, but with a semi-abandoned agricultural territory on the edge of the jungle on the border with India. Here, in the Gelephu area, Gelephu Mindfulness City will be born, a special administrative zone designed as an economic hub and international gateway to the kingdom.

“For 400 years Bhutan was really closed to any outside influence,” says Giulia Frittoli, partner at BIG and responsible for the urban and landscape masterplan, during the Holcim Foundation Awards 2025, the international competition focused on sustainable construction where the project was awarded. The closure helped preserve language, traditions and landscape, but today it results in a heavy dependence on tourism and hydropower, as well as the migration of younger generations to Australia or Canada. “The whole new generation is leaving the country.”

The crux of the master plan is legal as well as economic. "No one who is not Bhutanese can own even a piece of land or open a studio in Bhutan," Frittoli explains. That is why the king decided to establish a special economic zone in Gelephu with its own legal framework to attract businesses and talent from abroad. "The idea was to create a city that would allow Bhutan to grow while staying true to its values. To do that," he adds, "we had to figure out what those values really were."

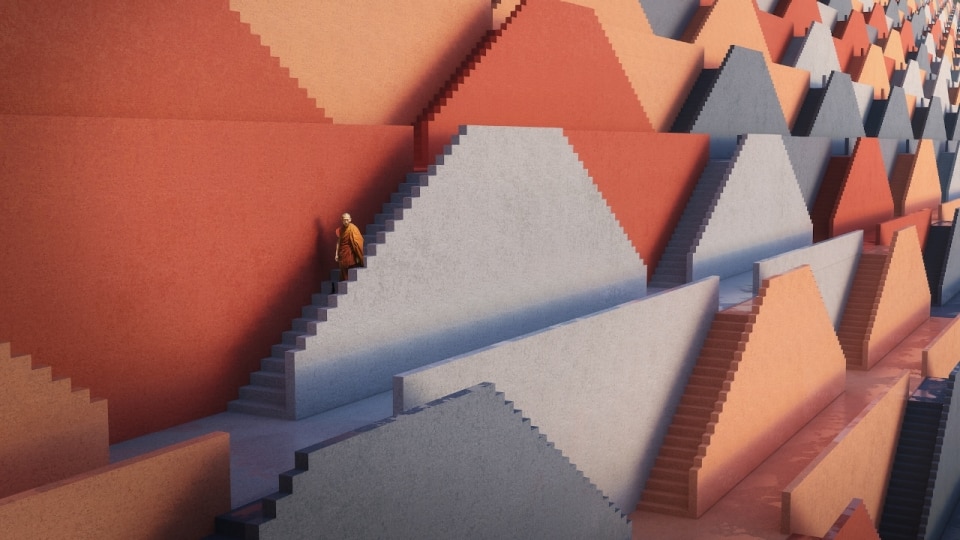

The reference is Gross National Happiness, an index introduced in the 1970s as an alternative to GDP. In BIG's work, its principles become three design domains-individual, environment, community-that guide urban design. "It was not just a matter of designing an efficient master plan," Frittoli summarizes, "but of building an environment that supports self-care, respect for nature and community living."

It was not just a matter of designing an efficient master plan, but of building an environment that supports self-care, respect for nature and community living.

Giulia Frittoli – partner at BIG and responsible for the urban and landscape master plan of Gelephu Mindfulness City

The transformation of the site starts with a gesture reversed from current practice: climbing the mountain overlooking the area, the team first maps rivers, canals, and ecological corridors not to be touched. "It became obvious that instead of starting with roads and buildings, we had to draw first the areas that should not be touched: the rivers, the water, the paths of the animals coming down from the Himalayas to India," Frittoli says. Out of this negative emerges a system of neighborhoods separated by waterways and connected by three major axes that also function as inhabited bridges; the plains along the rivers remain floodable fields and biodiversity corridors. The built will occupy about 4 percent of the area, the rest remains productive and natural landscape.

Numerically, on the other hand, Bhutan now has a population of about 700,000. Gelephu Mindfulness City is sized to grow to one million, with a first phase of about 100,000 people and development in stages until 2035. "We don't know who will move here or at what rate," Frittoli notes. "That's why we have built a very flexible, but at the same time highly planned structure to reduce the risk of mistakes." Frederik Lyng, partner at BIG and responsible for building types and the new airport, insists on this organic character: "The city can grow at different speeds, and the plan is designed to remain consistent even if growth stops in the middle."

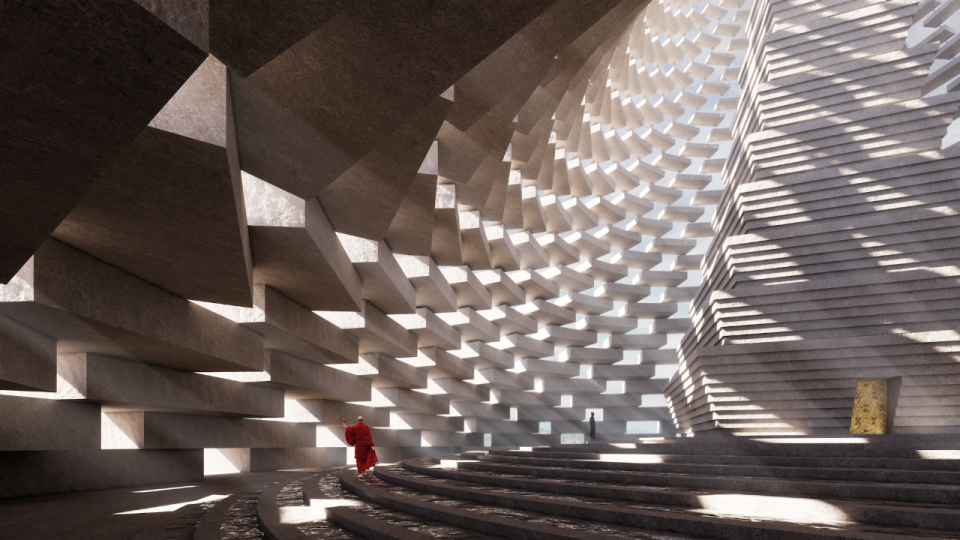

In defining the built environment, BIG starts with an almost nonexistent regulatory framework. "There is basically no building code; we could have done anything," Frittoli recalls. Instead, the firm chooses to impose strict limits on itself: no skyscrapers, heights between three and six stories to use almost exclusively structural wood and local stone, minimizing reinforced concrete and steel. This calls for the creation, in Gelephu, of an engineered wood supply chain. "For the first time, the country will be producing structural wood on a large scale," Lyng explains, "and we are helping them figure out how to do it right, in an earthquake-prone and wetland area."

Key element of the master plan is the new Gelephu International Airport, the country's second international aviation infrastructure. Designed by BIG with NACO, it is conceived as a large modular glulam structure, organized into freestanding frames that can be disassembled and reassembled. "The problem with growing airports is the sum of successive, often inconsistent additions," Lyng notes. "Here the ability to expand is already built into the structural system, so the building remains legible decades from now."

Half of the work is ours, the other half is given to the carvers and painters from the art schools, who complete the project and take on the authorship.

Frederik Lyng – partner at BIG and responsible for building types and the new Gelephu International Airport

In and around the airport, the project incorporates a strong craft dimension. Bhutan retains a tradition of crafts ranging from carpentry to painting, which is still very much present in the built landscape. "We don't deliver a 100 percent finished building," says Lyng. "Half of the work is ours, the other half is given to the carvers and painters from the art schools, who complete the project and take on the authorship." The same logic can be found in the initial stages of the construction site, when volunteers, members of the royal family, and residents participate in the controlled clearing of vegetation, mapping the trees and turning the wood into a resource for furniture and nonstructural elements.

In the current discourse on sustainable architecture, Gelephu Mindfulness City stands on an unusual scale. It is not the single certified building, but an attempt to rewrite master plan, building code, materials supply chain, financial instruments and even regulatory framework at the same time. "It is a city that, while opening up to global capital and businesses," Frittoli concludes, "remains readable as Bhutanese and not transferable elsewhere."