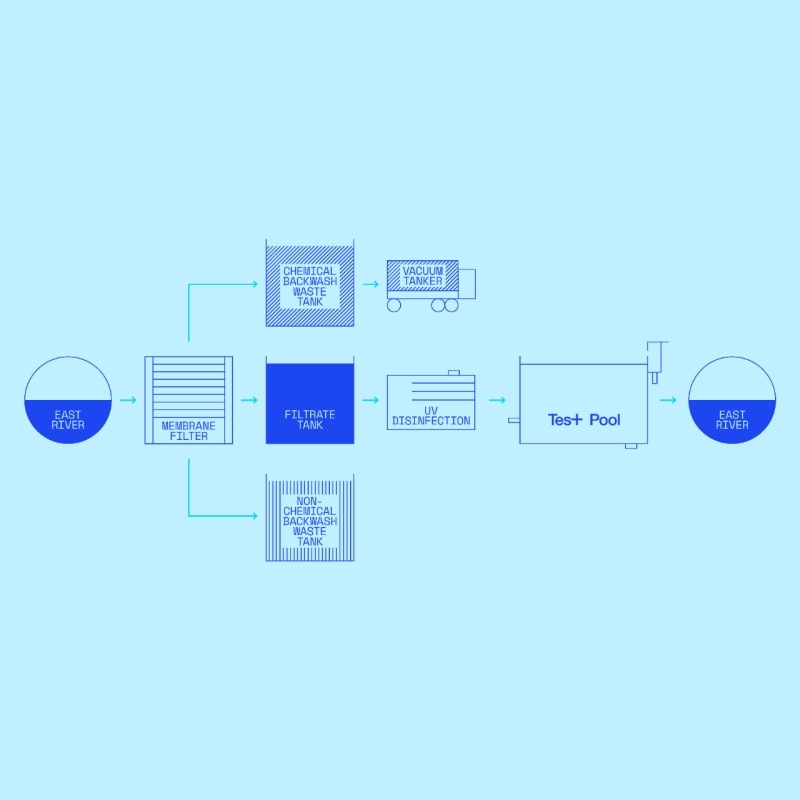

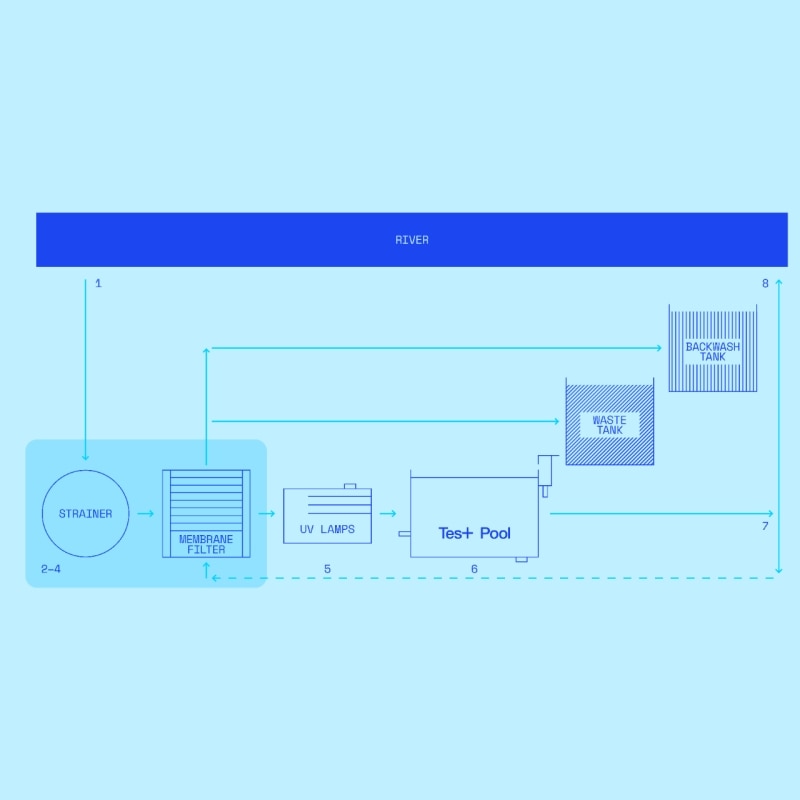

The + Pool project, the long-awaited floating pool capable of filtering river water, enters the prototyping phase in operation.

After this year's construction of the first floating structure - equal to an "arm" of the "+" of about 185 square meters - the team is building the integrated tank and filtration system. The goal is to complete the field validation of the recently approved rules and establish operational and maintenance procedures before the full version.

On the occasion of the Utopian Hours festival - ninth edition, theme "United Cities," October 17-19, 2025 at the Centrale - Nuvola Lavazza in Turin - Kara Meyer will speak on one of the panels dedicated to urban waterfronts and public infrastructure enabling new uses of water.

The idea was born in 2010 as a direct response to an urban need and immediately activated a community that enabled a Kickstarter campaign to be funded. Then, in 2015, the nonprofit charged with developing the project was formed; the pandemic slowed the course for about a year and a half as the focus of work gradually shifted to the regulatory framework. "One of the things we are most proud of is the regulatory work," explains Kara Meyer, managing director of the project. "If I can say anything to the project and design community, it's: go look at these new regulations and propose water projects in New York, because there's a pathway to do them today. And it doesn't have to be a plus-shaped pool-there is a path and variations. Read them, draw inspiration from them, and propose other ideas."

This makes the prototype not only a technical test, but a test bed for replicability and governance. The less visible but more structural result is now an administrative precedent: an official pathway, published on the websites of the relevant departments, that allows not only technically similar interventions to be proposed, but also bottom-up processes.

"We move into the terrain of policy change and project initiation. And I think that's the interesting part of + Pool: citizens can ask for something for their city, trigger it and work hard to develop it, without it necessarily having to be a top-down process," Meyer continues. "There are more infrastructural examples such as Paris, where 10 years ago the mayor declared that she wanted to make the Seine River swimmable. But we can also start from less ambitious projects-we have ignited a movement born out of the community."

On the economic/management level, the promoters hypothesize a potentially more affordable model than a traditional public pool, due to lower land incidence and use of river water.

The timeline, today, is marked by two steps: further full-scale testing in summer 2026 and, if successful, first season of public opening in summer 2027.

The timeline, as of today, is marked by two steps: further full-scale testing in summer 2026 and, if successful, first season of public opening in summer 2027. "This is the timeline; public partners and pathway are there. Unless the science fails-and the smaller-scale tests are encouraging-we are aiming for that date." Variables remain in the permitting process, verification of the performance of the filters in operation, and definition of the management structure.

Along with the construction site, the nonprofit has activated educational and social programs to prepare users and reduce economic and cultural barriers: learn-to-swim courses for thousands of children and adults, trails in schools, and outreach tools on water quality, including an installation that displayed real-time parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen, and enterococci. "When we get the facility, not everyone will be able to benefit if they don't know how to be in the water safely-that work needed to be started now."

The final location is planned in an area with historical environmental criticalities, at the active request of the local community. On the horizon, possible relocation of the model to other parts of the city-or to other cities-is now more feasible due to the combination of technical know-how and regulatory pathway. "We now know how to build it, and if your city does not have a process, we can advise on how to set it up. We can support grassroots movements and municipalities."

It all started, however, from a naive dream of young professionals. "I was working at Storefront for Art and Architecture and met the designers casually. The idea was simple, aspirational and beautiful: an example of how design can inspire a community. They had already done feasibility studies, raised funds on Kickstarter, and wanted to follow the High Line model by creating a nonprofit. They asked me to lead it. At first I said no, but they convinced me. That was ten years ago."