The future of the garden or the garden of the future? No, the garden is the future.

Throughout Western history, gardens have often been viewed as an enclosed, ordered space, a rational arrangement of species, and a symbol of human power over nature. Alternatively, they have been a utopian dream, a sign of our longing for a lost paradise or an idyllic state of nature destroyed by modernity. Recently, however, a new "militant" garden philosophy has emerged – one that envisions gardens as a blueprint for a future in which humans and nature not only coexist but collaborate.

The garden reveals the true essence of both artifice and nature.

Halfway between agrarian culture and untamed forest, the garden is not only a preserved ecosystem, habitat, biotope, or ecological reserve. Rather, it is a place where the actions of humans and nature intersect to form a hybrid environment – partly artificial, partly natural. Here, the garden reveals the true essence of both artifice and nature. This renewed understanding of gardens has sparked a reevaluation of contemporary spaces, from the home to the city. The garden indeed serves as an experimental ground for design, one that harmoniously engages both humanity and the natural world.

The garden, along with our deep connection to plants and the entire living world, has become the focus of numerous publications. Today, it’s almost impossible to find a bookstore without a dedicated section on the subject. Notable among these publications is the indispensable On the Necessity of Gardening, edited by Laurie Cluitmans (Valiz, 2021). Equally compelling is Earth Perfect? Nature, Utopia and the Garden, in which researchers Naomi Jacobs and Annette Giesecke pose a critical question: “Can a new ethos grounded in gardening lead us to a more sustainable relationship between humanity and the natural world?”. Further evidence of this trend can be seen in the increasing number of international exhibitions showcasing critical perspectives and innovative, radical projects.

.jpg)

Currently on view at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Garden Futures, Designing with Nature is a captivating showcase curated in collaboration with the esteemed Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam. The exhibition focuses on the design, social, and political dimensions of the garden. It explores the garden’s ability to serve as an act of resistance, resilience, and even guerrilla warfare.

In contrast to the mythical genealogy that makes the garden an isolated and exclusive space, an hortus conclusus, enclosed within physical and symbolic walls that separate it from the wild and urban chaos, a new wave of projects is presented here. These projects consider the garden as an inclusive space that seamlessly integrates nature into urban spaces and fosters collaborative dynamics. More importantly, it becomes a space for ecological co-design, based on the idea of a balanced relationship between humans and nature.

Ian McHarg, a renowned landscape architect, played a pivotal role in shaping this vision. His influential work, Design with Nature (1966), has left an indelible mark on generations of landscape designers and architects. Today, the same vision is embraced by leading figures such as Piet Oudolf, who designed the garden that covers Manhattan’s Highway, and Gilles Clément, who developed the concept of the “planetary garden”, which sees humans not as dominators of plant life, but as integral participants in a complex system of living organisms.

The garden or vegetable garden takes on an explicitly political role – it becomes a weapon to resist the overwhelming forces of urbanization.

For these gardener-philosophers, garden design combines aesthetics and ethics, implying an extended temporality that transcends the short-term logic of productivism. For others, however, the garden or vegetable garden takes on an explicitly political role – it becomes a weapon to resist the overwhelming forces of urbanization.

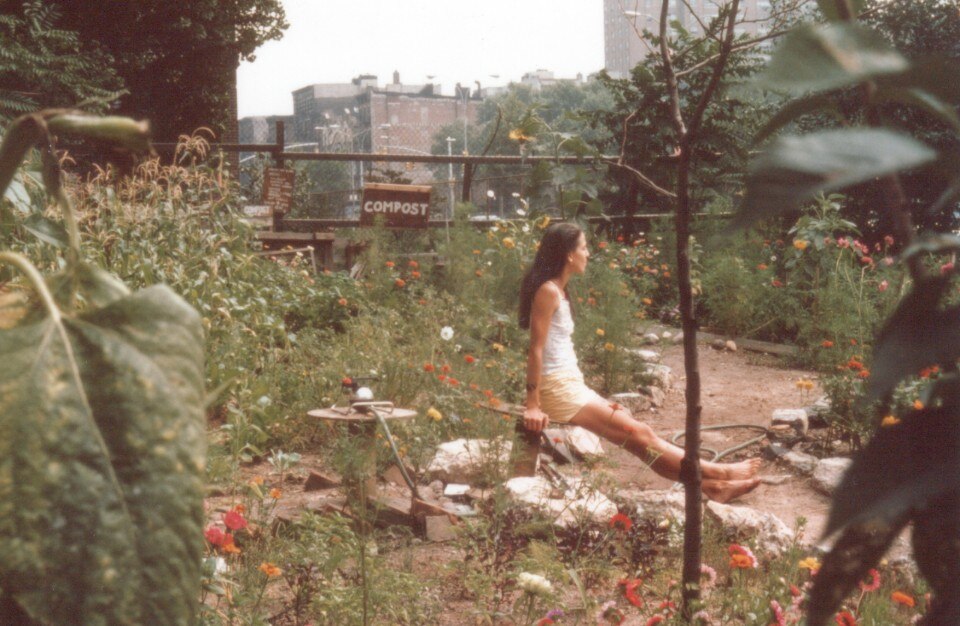

In recent decades, as awareness of the environmental crisis has grown, examples of “guerrilla gardens” have multiplied. In New York City, for example, as parts of the city fell into rapid decline in the late 1960s, some residents sought to reclaim abandoned spaces by occupying them with community and vegetable gardens. Similarly, in Kuala Lumpur, one of the world’s most densely populated megalopolises, a dedicated group of citizens has revitalized a wasteland beneath skyscrapers and high-tension wires, transforming it into the thriving Kebun-Kebun Bangsar Garden, teeming with plants and animals. Here, gardening serves as a tool for emancipation and identity building, while providing a space for exploring alternative, harmonious ways of living in balance with nature.

Can a new ethos grounded in gardening lead us to a more sustainable relationship between humanity and the natural world?

Earth Perfect? Nature, Utopia and the Garden, Naomi Jacobs, Annette Giesecke

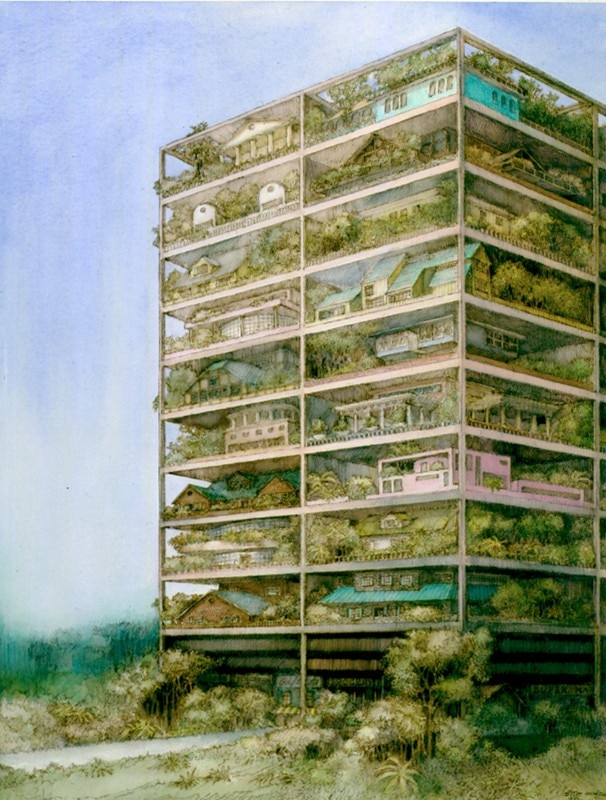

On the basis of these experiences, it seems possible to rethink our habitat, moving away from the perception of it as an urbanized and mineralized space where humans are the only living beings, to see it as a place where different species can coexist harmoniously. Many architects and urban planners have taken up the challenge of “greening” our cities, creating openings to introduce plant interspaces and create a more complex ecosystem and richer biodiversity. Notable examples include Stefano Boeri’s iconic Bosco Verticale and Bas Smets’ biospheric urbanism.

At the same time, young designers are paving the way for new, radical perspectives. Take for example Eugenia Morpurgo and Sophia Guggenberger’s Syntropia – currently on view at the ADI Design Museum in Milan in the not-to-be-missed exhibition Italy: the New Collective Landscape. Their innovative polyculture system makes it possible to build an entire manufacturing district locally, from materials to the final product. Similarly, Alice and Gavin Munro, founders of Full Grown in Devonshire, have embarked on an extraordinary journey. Their company uses ingenious techniques to literally “grow” chairs, turning them into trees. In their approach, the garden encompasses not only the city or manufacturing district but the factory itself. This is the essence of the garden revolution: design opening up to the complexity of life.

Opening image: Garden Futures: Designing with Nature, Vitra Design Museum. Stefano Boeri, Bosco Verticale, Milan, 2014 © Stefano Boeri Architetti, Photo: The Blink Fish, 2018

.jpg.foto.rmedium.png)

.jpg.foto.rmedium.png)

.jpg.foto.rmedium.png)

.jpg.foto.rmedium.png)

.jpg.foto.rmedium.png)

.jpg.foto.rmedium.png)

.jpg.foto.rmedium.png)

.jpg.foto.rmedium.png)

.jpg.foto.rmedium.png)