Uriel Orlow, whose large video and photo installation is on show at Manifesta in Palazzo Butera, is a courteous man and a complex artist. Each of his works is the result of years of study and personal relationships intertwined with people in a specific place. Usually an unresolved tangle from the past acts as the substrate for the work’s creation. In Palermo, he reflected on the city’s patron saint, a black cook, migrants who are also black and cooks, and Simona Mafai, a Jewish communist and senator and a proud opponent of the mafia. He created a dialogue connecting them with three trees representing three different moments in local Sicilian and national Italian history.

How did you manage to make the histories of the people so moving?

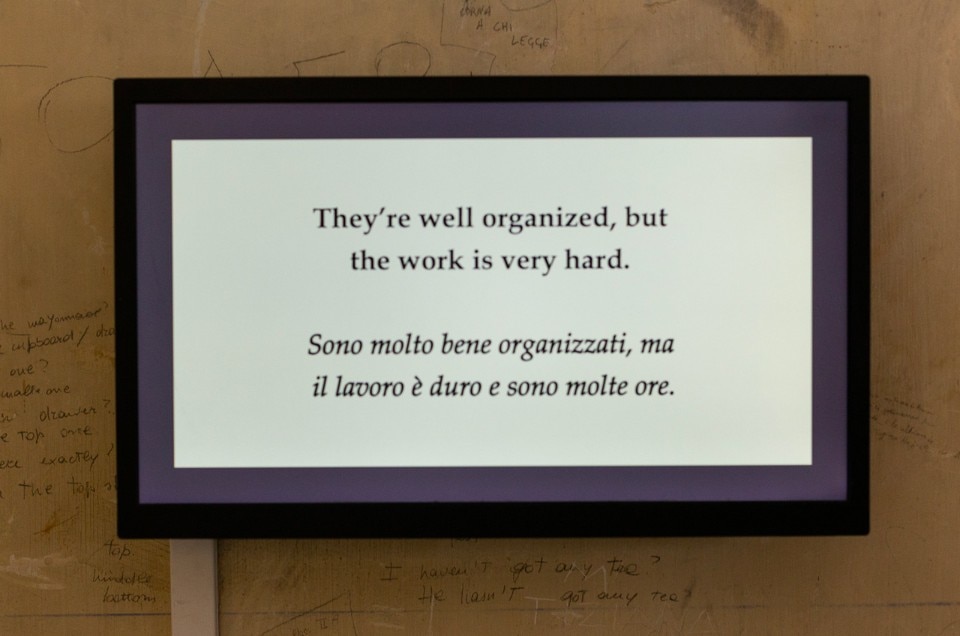

I believe it’s a question of time. It’s important to create relationships with people that extend across time. First with Simona Mafai and then with the cooks in the second video, we met several times in the space of a few months. I started the work by shooting in the kitchen where the guys were working, and this created a kind of intimacy since we were working in the same space. That developed into trust, which people need if they’re to tell their stories.

It’s interesting to note that these people are farmers, and this reminds me of when it was the Italians emigrating. How does agriculture relate to the theme of Manifesta?

Well, plants and subsistence are the basis of our lives. The migration of plants and people in relation to food is at the heart of the question. From this comes the concept of "The planetary garden” and the plant species that have migrated to Sicily. The orange tree is the most famous – it’s not native to the island. It’s important to remind ourselves that migration is not something that’s arisen in the last ten years. It’s nothing new: it’s part of how we inhabit the planet. We’ve moved over millennia and taken plants with us. What’s interesting about the histories of the cooks – two of them come from Senegal – is that they were subsistence farmers. I think there’s a lot of confusion about what subsistence farming is and what agriculture, on the other hand, is for us. They were working to survive – they didn’t feel they had a future. There was no chance to evolve or grow and this is one of the reasons why they emigrated.

You’ve chosen trees with powerful symbolic meaning. How did you understand the relationship between these trees and poetic representation?

What’s important for me is that the work exists on different levels. I do a lot of research and what interests me is the relationship that historical events – and the trees – have with the present. And how we relate to this present. Part of this happens through language and part through a poetic approach to the image. You need to create the sensation that something has happened but that it hasn’t necessarily been said – it’s not explicit. The history of the trees I’ve left to the trees themselves. I’m talking about the people that have a relationship with these trees today – Simona Mafai and the three cooks. The history contained within the tree is implicit. My focus is the present. There’s no need to narrate the trees’ history in our human language.

You’ve chosen markedly different people: three cooks and a woman who is very important for Sicily, from a political point of view. Is politics important for your work?

I think that politics is involved in whatever we do. Even when we go to the supermarket, we’re entering a political space. As an artist I’m a little weary of the idea of political art, but equally of ostensibly non-political or purely formal art. In my view, it’s a continuum, not a label. Living in this world and being committed as an artist means I’ve chosen to think about what’s happening, about the relationships between visibility and invisibility, between power and the lack of it, about hidden history or what’s conspicuous – everything that comes into the way I think and work. It doesn’t seem to me that there’s anything extraordinary in this. Rather, I’d say that it’s very ordinary. I believe that to some extent all art is political in different ways insofar as it’s a representation of the world and how it’s structured.

What about colonialism?

Let’s take a step back then. I’m interested in ghosts. If we’re thinking about ghosts in the literal sense, we have to think about unfinished business from the past. Something is a ghost when it comes out of the past to haunt us because it can’t rest in peace. It’s about unresolved events that are often tied to problems of justice. A lot of popular cinema is based on this assumption. We live with ghosts but the point is that they’re not from the past but the present. The question of colonialism is exactly that – a question of ghosts.

But there’s also neo-colonialism…

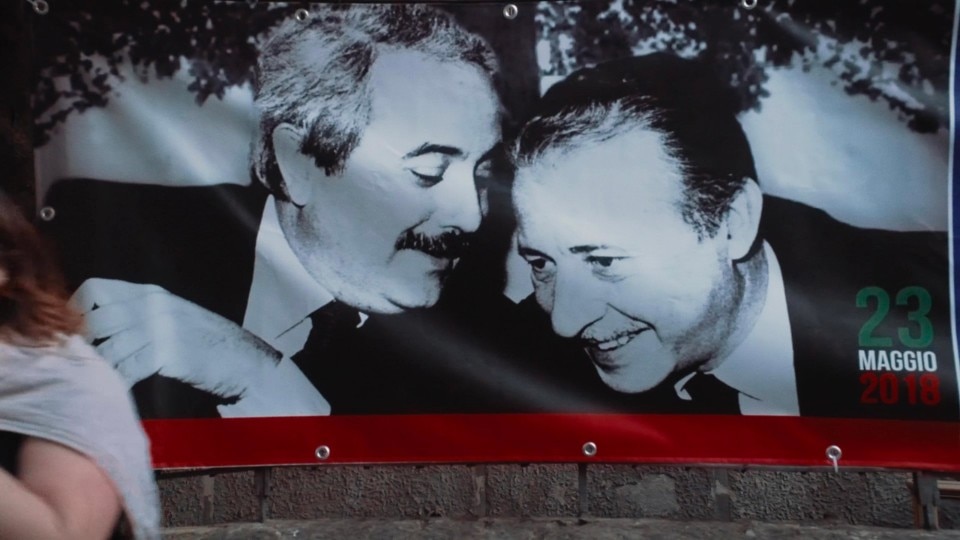

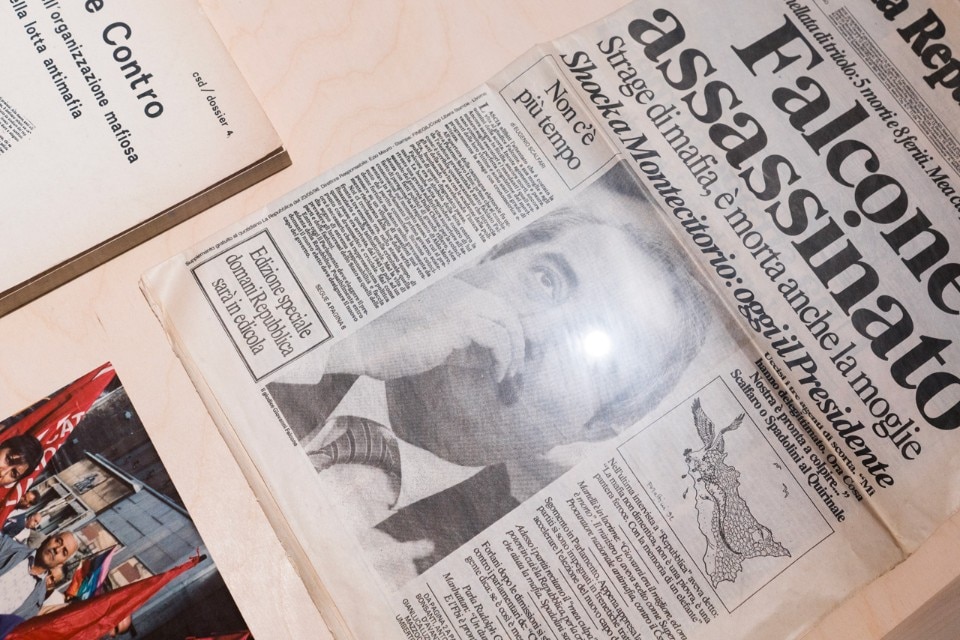

There are problems of justice that have never been tackled and they return today. Senegal, for example, where I’ve been working on my next project, which relates to agriculture, is no longer a colony but the colonial structures are still in force, and so is exploitation. For me, it’s important to understand the effects of this in the present. The histories of these cooks are closely tied to all this – their lives are still conditioned by colonial relationships. And it’s because of this, to broaden the discussion, that I’m interested in a person like Simona Mafai. She’s brought together different struggles, for women’s and workers’ rights, for abortion, against violence against women, against the mafia. It’s this capacity to hold all this together that has made hers an extraordinary life. And you need to hold this together because otherwise you risk having people who are against the mafia and then go home and hit their wives. In other words, violence is transversal – it includes colonial structures and domestic violence – which is why I’ve brought these stories together.

With your emphasis on migration and farming, nature seems to play a central role in your work.

Yes, in recent years, yes it has. I’ve just finished a a large body of work called Theatrum botanicum, also now a book, which started life in South Africa. I began by thinking about the relationships between plants and politics, between plants and history, something that doesn’t seem at all obvious because we tend to think of plants as neutral. In fact, they’re heavily implicated in colonialism and this is a theme that continues to interest me. It’s also important for me in terms of representation, and in particular how we can represent history from the perspective of plants. This may be a representation of silence or even a non-representation, which is why in the video of the trees there’s no explanation or even a soundtrack on the two projections.