This article was originally published on the supplement of Domus 1039, October 2019

The architectural practice UNStudio, based in Amsterdam, recently revealed a rather unusual project in a flurry of online videos and press releases. The initiative has nothing to do with designing a building or an urban area. Instead, it aims to promote a new paint for use on metal facades, which has been cleverly dubbed The Coolest White. Developed in collaboration with Swiss manufacturer Monopol Colors, this whiter than white paint will prevent walls from heating excessively by boosting reflection of solar radiation, as well as being highly resistant to abrasion.

With this ambitious project, UNStudio is seeking to reduce the urban heat island effect by applying the paint to a large number of buildings. Energy consumption linked to air conditioning in cities could therefore be significantly reduced, protecting the environment by extension. In other words, The Coolest White could be one of the key elements in green urbanism according to UNStudio, which already plans to implement the project in a large city in Southeast Asia.

A whitewashing operation

In this project, UNStudio acts as a full service provider rather than a mere architecture and design consultant. The studio’s stated aim is to develop new technologies that can resolve the major social and environmental problems caused by urban growth. This progressive line echoes the approach of certain exponents of modernism in the last century, and raises several questions. Promotion of this “revolutionary paint” comes across with the typical contemporary rhetoric surrounding innovation, whereby existing or alternative solutions are usually omitted from the conversation. Indeed, painting buildings white to minimise heating is an ancestral practice in the hottest regions, and the extent to which The Coolest White will reduce absorption of solar radiation more effectively than brushed limewash is open to debate. Rather than progress, is this not instead a primarily commercial operation, which seeks to replace traditional, proven methods with a new industrial product?

Would a high-rise building made from glass and steel really be more ecological if it were painted white, given the grey energy trapped within it and the urban developments it would entail?

Moreover, UNStudio makes no comment on the architecture that would lie beneath this immaculate skin. Would a high-rise building made from glass and steel really be more ecological if it were painted white, given the grey energy trapped within it and the urban developments it would entail? The marketing operation launched by UNStudio and Monopol Colors appears to pave the way for the whitewashing of a development model that actually contributes to the environmental crisis, especially in tropical regions. Last but not least, given that The Coolest White is a fluoropolymer-based paint derived from the petrochemical industry, can its production on a very large scale truly be viewed as a “movement” to solve the world’s problems, as the owner of Monopol Colors pompously claims?

A dream of purity

Besides the fact that UNStudio’s project is driven by a naive or cynical (depending on one’s point of view) faith in technological progress and economic growth, it is also underpinned by a powerful cultural prejudice that merits further analysis. The idea of an entire city painted white recalls a utopian vision rooted in neoclassical thinking. In this way architects and sculptors alike have prioritised form over colour since the Renaissance, and white became accepted as the true expression of beauty from the 19th century following the work of archaeologist Johann Winckelmann.

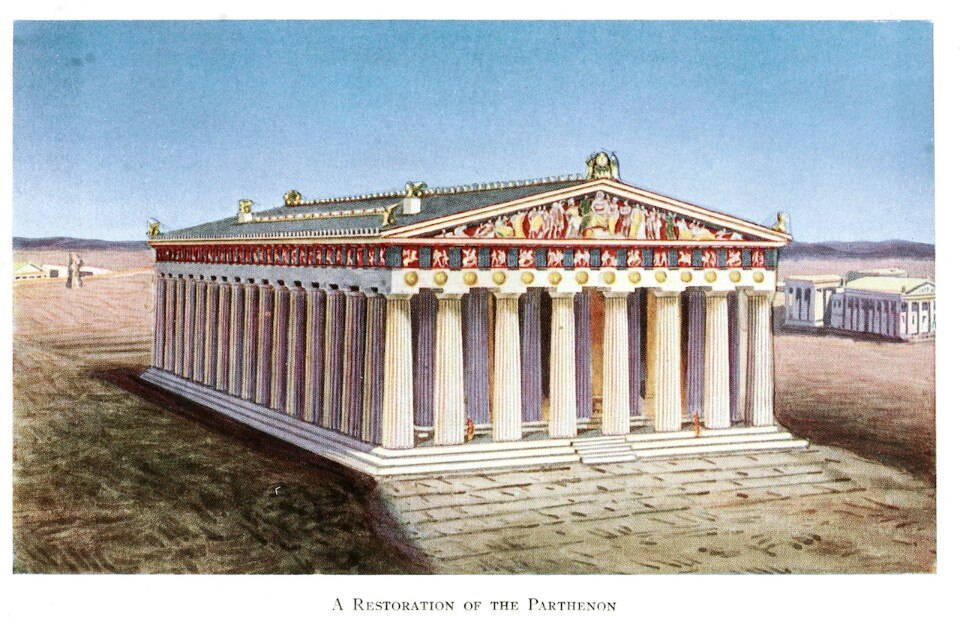

Most European and American architects returning from their Grand Tour drew inspiration from Roman and Greek antiquity, epitomised by the Acropolis and the Parthenon in Athens built with Parian marble, renowned for its whiteness. It should be noted that this preference for white was based on a misunderstanding, as the statues and buildings in question were actually polychrome before their colours faded through exposure to the weather or to the work of clumsy restorers. Nevertheless, for the modernist architects of yesteryear, as well as for those working today, whiteness came to symbolise rationality, purity and the superiority of Western civilisation. In comparison, the complex, archaic Orient was depicted as full of colour and decorative elements.

Not surprisingly, in the 20th-century colonial imagination, white architecture became known around the world as architecture designed by and for white people. Curiously, the symposium titled “The Whiteness of American Architecture”, which was recently held at the University of Buffalo in the United States, does not appear to have explored this issue in its more direct signification. With its plans to create an entire Asian city coated in The Coolest White, UNStudio asserts its avant-gardism by somehow reconnecting with an ethnocentric and overarching approach.

Chromophobia

Of course, these considerations go beyond the mere launch of a new paint. More generally, they concern a current tendency of numerous architects to design immaculately white buildings. From this perspective, it would appear that a historical interlude has come to an end. Indeed, in the 1970s and 1980s, a healthy critique of the Modern Movement’s abstraction and elitism led to the reinstatement of symbolism and decoration, as well as polychromy. In the United States, the architects known as “the Whites” (Eisenman, Gwathmey, Meier, etc.) came into conflict with “the Grays” (Moore, Venturi, Stern, etc.), who called for the use of bright colours as a way of re-establishing contact with the general public.

Many postmodern architects drew on the vitality, fantasy and even the impurity of popular, commercial constructions in order to revitalise a “high culture” that they viewed as completely sterile. Today, architecture has once again become very serious, sometimes to the point of boredom. Architectural journals and specialised websites are packed with projects that are based on very clear-cut, very clean compositions of volumes whose whiteness shines under the radiant sun. That is photogenic, but do these stylish buildings reflect the diversity and cultural richness of contemporary cities? They appear instead to indicate a concern among many architects to distinguish more than ever their creations from ordinary and colourful buildings.

Valéry Didelon is a critic and historian of architecture. He is professor at the École nationale supérieure d’architecture of Paris-Malaquais, where he teaches design and theory.