This article was originally published on Domus 1036, June 2019

Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, is the original oil city: a cosmopolis built on and by oil. Ever since Baku’s first oil boom in the 1870s, when local oil barons channelled their profits into the city, investing in institution building, representation and the public life of citizens, oil and urbanism have been inextricably linked in the fabric of the city. By the 1890s foreign capital had penetrated deep into the Baku oil economy.

The oil industry itself was modernised by European producers and investors – most notably the Russian branch of the Nobel family and the French Rothschilds, who were followed by British-, French-, German-, Belgian- and Greek-owned companies. By 1901 Baku had become the world’s largest supplier of oil and was known as the “Paris of the Caspian”, a cosmopolitan European city with a business elite, educated bourgeoisie and an urban environment of tree-lined boulevards, monumental public buildings and a rich array of cultural institutions, from theatres and museums, to academies, newspapers and modern communication networks.

Today – following 70 years of Soviet rule (when Baku was the site of an experiment: to shape an “oil city of socialist man”), and post-socialist transition in the 1990s – Baku is once again one of the most dynamic and rapidly changing urban environments in the world. This is largely the result of a major oil boom (Baku’s third) that began in the mid-2000s with the opening of the BTC (Baku-Tbilisi-Cey- han) pipeline channelling oil and gas (via Turkey) to Europe and the EU’s single market, and was given a significant boost in 2013 with the Shah Deniz Project and Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP).

Currently the largest urban architectural project underway in Baku is the White City. Envisioned as a vast new CBD comprising ten inner-city districts, with office towers, hotels, commercial, residential and cultural buildings, new subway lines, a coastal tram line and new thoroughfares, it includes the newly monumentalised Heydar Aliyev Boulevard that connects the White City to Baku’s expanded Heydar Aliyev International Airport. This highway is rapidly becoming the spine for a swathe of new urban districts between the White City and the airport.

Part of a massive building and remediation programme launched by presidential decree in 2006, the White City occupies 221 hectares at the centre of Baku Bay. Designed by Atkins and Foster + Partners, it is replacing the old industrial districts of Baku, the Black Town and White Town, where the first oil refineries and the Nobel Brothers’ factories and Villa Petrolea were once located, and where the cluster of technological innovations that gave Baku the competitive edge in worldwide oil production at the turn of the 20th century occurred.

Like these early industrial districts, White City is conceived with enormous ambition and on an unprecedented scale. But its programme is decidedly post-industrial. Once completed, the White City will cover 4 million square metres of gross floor area, of which 75 per cent will be residential. According to Matthew Tribe, director of master planning and design for Atkins, Dubai was an important reference for Baku’s White City. But the forms and spaces of the new fabric suggest a different model. Instead of Dubai, they evoke the late-19th-century arrondissements of Louis-Napoléon’s Second Empire Paris with their monumental stone-clad buildings, public squares, parks and grand avenues.

As such, they clearly hark back to Baku’s late-19th-century identity as the “Paris of the Caspian”. The analogy goes further: like the largescale demolitions carried out by Baron Haussmann to make way for the new avenues and apartment blocks of late-19th-century Paris, the removal of neighbourhoods to make way for new construction in the White City is also displacing thousands of residents.

Elsewhere in downtown, the scale leaps to that of La Defense and the Grands Projets of Par- is in the 1980s. These include office towers, hotels, commercial centres and cultural landmarks designed by international star architects, strategically placed for optimum viewing in public squares and parks in the city centre.

The programme’s centrepiece, launched in 2007, is Zaha Hadid’s Heydar Aliyev Cultural Center (com- pleted in 2012), followed by the Carpet Museum designed by Austrian architect Franz Janz (completed in 2014), and the iconic Flame Towers designed by HOK (completed in 2013). Baku’s public building programme has enormous symbolic significance locally. In the words of Azerbaijan’s minister of foreign affairs Elmar Mammadyarov, “It signals my country’s re-emergence into the international community and enables us to showcase our achievements since independence.”

The expanses of glazing and prismatic geometries of the new towers also firmly situate Baku’s new CBD in synchrony with the ethos of Dubai and other capitals of oil-rich states.

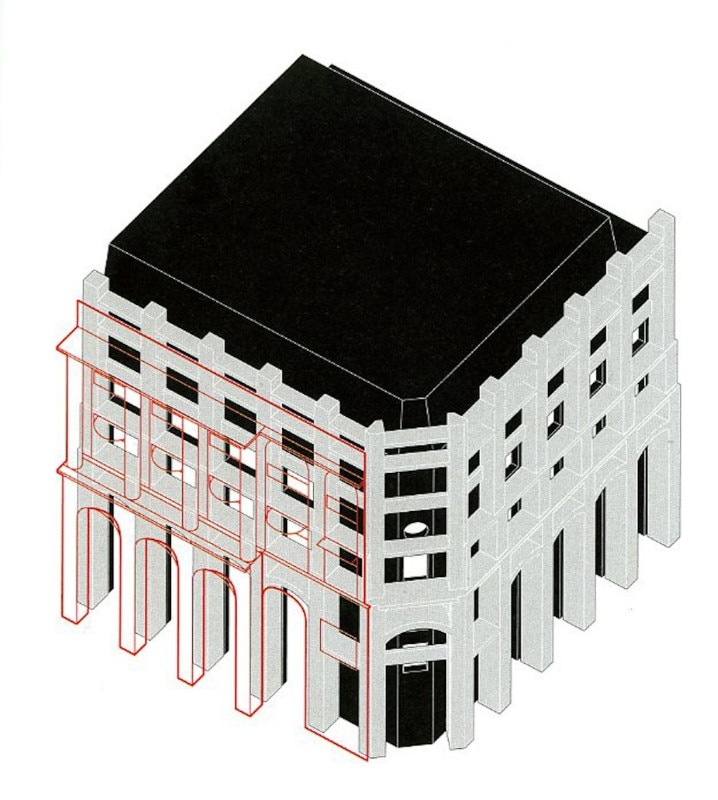

In many ways, the urban project that resonates most strongly with Baku’s current aspirations – but that is also deeply haunted by the city’s past – is the government-sponsored limestone recladding of Soviet-era panel buildings. Concentrated on the major boulevards of the centre, the recladding is directed at generating representational streetscapes and consolidated urban fabric.

While it may evoke Haussmannian Paris in its forms, it reprises the Stalinist practice of three-dimensional ensemble planning, where assemblages of buildings, urban infrastructure and landscape elements are composed as an integrated architectonic unity to generate a geometrically ordered swathe of urban fabric: an “ensemble”. Like the earlier Soviet ensembles, the recladding is scenographic and skin-deep.

It is a variant of “Potemkin-city” urbanism that gives coherent and monumental shape to the urban streetscape, while hiding the dilapidated and unregulated construction that lies behind. But the recladding programme also adds a new element to the ensemble formula.

The limestone facades, which are elaborately carved with deeply undercut classicising ornament, are not mere facing. They are shells that encase the old buildings and enlarge their internal spaces – merging socialist and capitalist space – and in the process transforming both in the creation of an anomalistic hybrid. Harking back to both the Oil Baron and the Stalinist periods, as well as to the Brezhnevite “thriving city of socialism” in the 1970s, while preserving the still-solid building stock of the Khrushchev period – and combining all these “period styles” with the local stone masonry and craft traditions of the Absheron Peninsula – the new urban architecture of Baku is a matryoshka of contradictions.

As they embark on a new phase of urban development associated with Baku’s third major oil boom, government officials, planners and those responsible for shaping the city’s economic future apparently see the legacy of the past as a resource that sustains new identities and aspirations. They are looking to Baku’s early capitalist history, and are reworking practices established during Baku’s first oil boom and period of modernisation.

In particular, they are looking to the turn-of-the-century Azerbaijani oil barons who first staked their claim to the city and its resources, and then channelled their profits into creating a vibrant urban environment. But that legacy also includes Baku’s boomtown origins as the oldest oil extraction site.

Today, like 100 years ago, oil is ever-present in the urban landscape and permeates the daily lives of Baku’s population. Outside the centre, the network of multi-gauge pipes that channel oil (as well as gas and water) through the city are the most resonant monuments in contemporary Baku. Today, as the city heads into an uncertain post-oil future, Baku’s densely interwoven urban and industrial infrastructures give form to the material and social foundations on which the city was built.

More powerfully than the spectacular new skyscrapers, pristine limestone facades, new concert halls and parks built in the last decade, the hard-working infrastructures of oil speak of the innovative industrial practices and philanthropy of the oil barons. They also make tangible the early Soviet aspiration to shape a new kind of industrial city, and they ground the current ambition of Azerbaijan’s oil-rich capital to become the metropolitan hub of a 21st-century Silk Road linking Asia and Europe – binding the city to its industrial past and anchoring it in the oil-rich bedrock that underpins its wealth.

Eve Blau teaches at the GSD Harvard University and is the author (with Ivan Rupnik) of Baku. Oil and Urbanism (Park Books, Zurich 2018).

Opening picture: view of Fizuli Street, downtown Baku; in the background a 19th-century Parisian-style building. Photo Ilkin Huseynov