This article was originally published on Domus 1042, January 2020

It is already the early hours of the afternoon, but Muharraq is still motionless in the sun, which is no longer very high in the sky on this autumn day. A steady breeze blows from the sea that almost completely encircles the old pearl-fishing capital jutting into the Persian Gulf. Opposite the municipal bus station, the narrow side of a singular building attracts attention. Above a reddish concrete wall rises a flat broad-span roof.

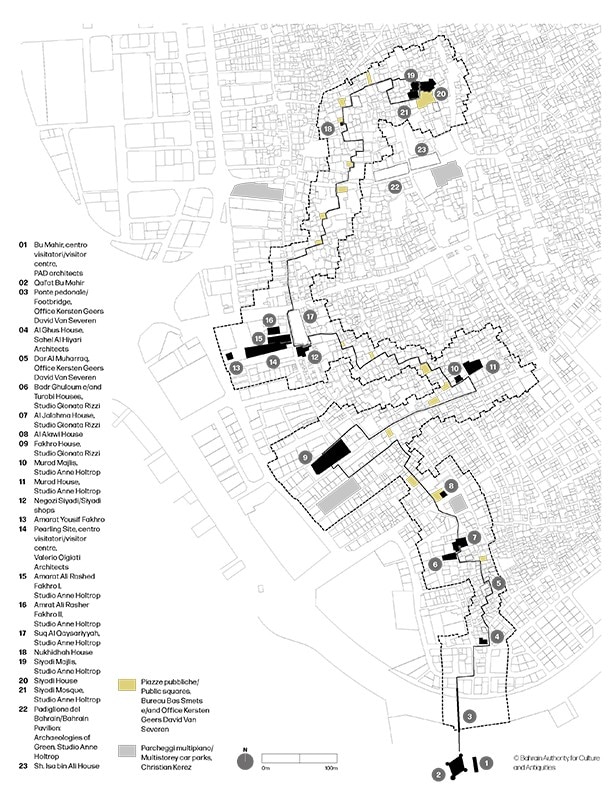

This is the Visitor Centre of the Pearling Path (officially the Pearling Path, Testimony of an Island Economy) in the old capital Muharraq, the second of Bahrain’s three UNESCO World Heritage Sites, located in the heart of Muharraq. The city has had to yielded its political and economic role to nearby Manama, but it has retained the character of an Oriental city with its dwellings, workplaces and religious activities all huddled together. Along an often tortuous route 3.5 kilometres (2.2 miles) long, the Pearling Path comprises three oyster beds in the open sea and an old fort at the head of the island, together with 17 historic buildings, protected as monuments and suitably restored together with a series of architectural projects in the fragmented urban structure. The most significant of these projects is Valerio Olgiati’s Visitor Centre.

The oil boom of the late 20th century wrenched the small riparian states of the Persian Gulf from their earlier life in ways never experienced before, projecting them into the present, or rather a kind of future. Until then, ignored by history, they had led an existence on the fringes of global politics, before the appetite for fossil energy placed them at the centre of world-shaking events. The greater the wealth spilling suddenly from local mineral resources into small feudal states, as in a fable from the Thousand and One Nights, the more violent the leap into a condition that seemed to fulfil the fantasies of the Universal Expos of mid-century rather than any comprehensible development. The previous condition, including the feudal structure of the state itself, was elbowed out of sight by glittering skyscrapers, multi-lane highways and artificial islands.

Bahrain’s surprising and stimulating contribution to the Architecture Biennale in 2010, acknowledged with the Leone d’Oro, documented the sense of loss just described with the testimonies of individual citizens and some private attempts to restore its earlier bond with the sea in various ways, including building temporary beach huts. But in Muharraq itself, the former centre of pearl fishing and trading, the relationship with the sea was literally buried by earthworks located all around the peninsula, eliminating its ancient ragged coastline and replacing it by, among much else, a multi-lane highway that completely cuts the city off from the sea. To date there is not even a pedestrian bridge spanning the highway to the historic Fort Bu Maher, once located on a small island and today, thanks to the new artificial landforms, joined to Muharraq.

The additions to the UNESCO World Heritage list are an important factor in the National Strategy for the Economic Vision 2030. In terms of a critical approach to architecture, the challenge of a World Heritage Site with such a functional nature would lie in making its non-physical components recognisable or, conversely, in characterising and making the existing material remains comprehensible, in particular the structures, by expressing a significance that goes beyond their mere character as buildings.

Valerio Olgiati’s Visitor Centre can only be understood in this context. When you access the building by the front entrance set in the high surrounding wall, it appears as a broad, long surface covered by an irregularly shaped roof. It is actually a flat roof supported by pillars, pierced by slender towers and interspersed with pentagonal apertures. This is clearly a modern interpretation of the ancient wind towers erected in many Eastern countries to ventilate and cool interiors in a natural way.

The roof rises some ten metres above grade. Pentagonal apertures are inlaid across its surface. However, this roof does not cover a building, and even the wind towers do not lead inside a building. The pentagonal openings in the roof surface perform no other function than allowing the sun’s rays to reach the paving unobstructed, so creating a fascinating pattern of constantly chequered light and shade. All around, the whole surface area, extraordinarily spacious, is surrounded by tall concrete walls. Closer to the narrow anterior side stands a block-shaped building, almost windowless. Its form is that of a building with a pitched roof, but actually built as a monolith. Rather surprisingly, it is positioned laterally and extends the ridge line of the roof with its sharp edges into the adjacent space.

Deep inside the site, the wind towers alternate with thinner pillars arranged in straight rows on the flat surface paved with concrete. Suddenly ruins or parts of ruined buildings appear, long walls of light local stone, typical of the oyster beds. In the further extension of the land, there are added rows of masonry pillars, partly braced against each other with wooden roundels that most likely had the function of supporting canopies or tents – the scaffolding of a souk, a traditional market. In the depths of the site some areas have been isolated and preserved, such as excavated foundations and the remains of the walls of previous buildings. These carefully preserved ruins are not really “ancient”. They are market buildings dating from the 1930s, which in the course of Bahrain’s economic transformation fell into disrepair. The message is obvious to everyone. Today’s Muharraq stands on the remains of the previous urban settlement and the physical excavation in depth simultaneously denotes an awareness of the stratifications of the past, awareness of the historical heritage.

It is the rejection of any architectural quotation that gives the building its particular significance

The Visitor Centre stands out in the densely built-up old town of Muharraq. It is more impressive than any other building in the immediate vicinity and it is not clear whether it is simply a covered square or a whole complex. It is at the same time open and protective, has no partitions yet is clearly bounded by its walls and doors. The fact that there is an independent building beneath its roof, also characterised by a monolithic shape, makes the remaining covered area seem all the more like a clear space. On the other hand, the ruins that rise in the area at the rear of the site and the excavations create the impression we are in a shelter, similar to the protective pavilions built in Chur by Peter Zumthor early in his career as an architect.

The ambiguous significance of the structure prompts visitors to try and understand what they can or ought to do here. At the same time, the indeterminacy opens up possibilities that still have to be discovered and experienced by Muharraq’s inhabitants. On the whole, the work is an example of the “non-referential architecture” theorised by Olgiati, an architecture that refers to nothing outside itself. Only with the wind towers does he use a traditional type of construction, a regional feature, but he does it only for the sake of its function and not its concrete form. He avoids any allusion, any juxtaposition to local or regional constructional forms. It is also true that there were no known prototypes for the design of a visitor centre, or more generally a spacious covered area, unless we invoke models of Eastern architecture that are not only geographically but also typologically remote, such as the Hasht Behesht pavilion in Isfahan dating from the Persian Safavid period or the Mughal audience hall at Fatehpur Sikri in India.

Olgiati himself, however, vigorously rejects any possibility of reference. In a broad theoretical essay he speaks of “non-referential architecture”, meaning the loss of any objectively valid benchmark. “Even if it is inevitable that architecture always takes on a social task,” he writes in his essay Non-Referential Architecture (Simonett & Baer, 2018), “buildings can no longer be derived from a common social ideal.” A “non- referential building” assumes “its significance and meaning only from itself.” Set against this theoretical background, the impression of the Visitor Centre’s extraneousness to an environment with a traditional character like Muharraq seems to express a refusal to establish a reference of either a historical or stylistic kind. “Non-referential architecture,” writes Olgiati, “does not mean constructing a building or a city according to a certain style, nor does it require any form of ideology – hence no style or ideology which an architect, builder, town planner or politician they could invoke.”

It is precisely the rejection of any architectural quotation that gives the building its particular significance. This demonstrates that the necessary work of preserving the historic structures along the Pearling Path is compatible with a productive rethinking of architecture. The economy and the social reality of pearl fishing belong to the past. Nothing can bring them back to life. They can only be preserved in the form of the historical document and only if it enters into a vital exchange with contemporary reality.

The problem of the architectural complex is the wall. As in a fortification, it surrounds the site on all sides and is interrupted only by four double steel doors that are no less forbidding. The protection of ruins and excavations undoubtedly calls for particular attention in a country characterised by rapid change and frequently reckless demolition of its oldest buildings. However, at the same time, it makes spontaneous and unintentional access to the area psychologically more difficult. A spontaneous coming and going, as in the open square of Djemaa el Fna in the Moroccan city of Marrakech, would be unthinkable in Muharraq. Although the Visitor Centre is not really a square set in the middle of the urban fabric but rather a space that opens up within a densely built-up area. Completion of the nearby Suk Al Qaysariyyah by Anne Holtrop is likely to lead to a shared use of the covered open space.

Are the dimensions of the Visitor Centre too great, or at least the surrounding walls too forbidding? These are questions that not even Noura al Sayeh, head of the Architecture department at the Ministry of Culture of Bahrain, finds it easy to answer. Well known as the curator of the country’s contribution to the 2010 Biennale, she believes that in the last few decades people have experienced the privatisation of public areas, or those accessible to the public, and for this reason they still refuse to accept the offer of newly created public spaces.

The inhibition threshold would be high – so she declared in an interview – and the inhabitants at first would avoid even the small urban squares of the Pearling Path. Precisely for this reason a broad offering of events is planned above all in the building of the Visitor Centre, to gradually overcome this resistance through participation. The surrounding walls, on the other hand, are necessary to protect the ruins and excavations from damage.

The ambiguous significance of the structure prompts visitors to try and understand what they can or ought to do here

In comparison with the large scale of Olgiati’s architecture, the Pearling Path also ends up seeming almost inconspicuous. However, its ambition is great. “The project both highlights the town’s pearling history and aims to re-balance its demographic makeup, enticing local families back through improvements of the environment and the provision of community and cultural venues,” reads the project description that was the basis for the prestigious Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2019. The Path as such was created by the Belgian practice Office Kersten Geers David Van Severen. The architects have marked the path with lamps spaced out at irregular distances along the route, above all at corners and intersections. Then the practice created sixteen squares, small in size but large by their urban effect. For the squares, their furnishings and the illuminating stelae that line the route, the architects used Venetian seminato in mother-of-pearl encrusted concrete flooring, commemorating the “path of pearls” as a reminder of the city’s past economy.

In any case, the excellent central position of the Visitor Centre is not only an opportunity but also a pledge that it will play a significant role in the urban structure of Muharraq. First of all for its inhabitants, seeking a new and lasting role for their city in a constantly changing world.

- Project:

- Pearling Site

- Program:

- visitor center

- Architect:

- Valerio Olgiati

- Design team:

- Sofia Albrigo (project manager), Anthony Bonnici

- General contractor:

- Almoayyed Contracting Group

- Local architect:

- Emaar Engineering

- Client:

- Bahrain Authority of Culture and Antiquities

- Location:

- Muharraq, Bahrain

- Built area:

- 6,726 sqm

- Completion:

- 2019