In design, we have become accustomed to certain boundaries dissolving. Consider, for example, the distinction between indoor and outdoor spaces, which is becoming increasingly blurred thanks to hybrid materials, versatile furnishings and a concept of comfort that transcends the boundaries of home and away. However, the separation between living and working remains much more rigid.

The concepts of home and office continue to evoke different images and functions, often with opposing spatial, cultural and design implications. As needs change, so do the gestures that inhabit these two worlds — and, as a result, design has developed along parallel tracks. In recent years, however, this has begun to change. Smart working has introduced new habits, and the pandemic has accelerated a change that shows no sign of stopping. Many people now work from home, although their homes are still mostly furnished for living, not working.

Yet there is furniture that can move nimbly between the two spheres. Work tables, technical lighting and functional drawers are designs created for efficiency, yet capable of adapting to comfort. They are versatile, essential and well-designed objects that look good even outside the context for which they were intended. We have selected five pieces of office furniture that we would like to have (or already have) in our homes. After all, good design is design that finds its place anywhere.

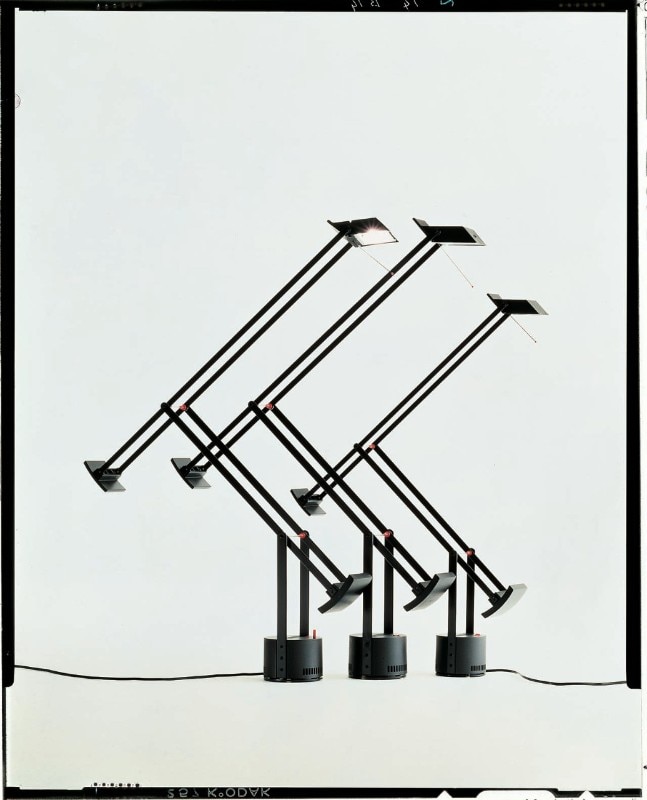

A light for all surfaces

“It’s beautiful in any position, harmonious in all its parts,” said Artemide’s founder Ernesto Gismondi — a fitting summary of this groundbreaking desk lamp’s cross-sector success. Tizio was the first of its kind and inspired countless future designs. Its innovation lies in taking up very little space while offering great freedom of movement — achieved through its now-iconic design: double aluminum arms coated in nylon and fiberglass, balanced by counterweights. More a “surface” lamp than just a desk light, it adapts to any setting, won the Compasso d’Oro in 1979, and is part of the collections at MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum, and London’s V&A.

A modular system turned into a global icon

View gallery

View gallery

One wonders whether, back in the 1960s when Paul Schärer and Fritz Haller designed the furniture for USM’s new headquarters in Munsingen, Switzerland, they realized they were launching a design revolution. Released commercially in 1965, the system is modular and based on just three elements: steel tubes, metal or glass panels, and chrome-plated brass ball joints. These elements, together with standardized measurements and proportions, transformed an office system into a design icon of remarkable versatility. Over the past seven decades, USM Haller has appeared in homes, public buildings, and showrooms worldwide — even inspiring artistic and fashion collaborations, as well as creative hacks that reinvent its use.

A chest of drawers that moves, with a strong identity

View gallery

View gallery

It’s a drawer unit — it stores things, it does its job. But there must be other reasons for its success and for its Compasso d’Oro win in 1994. Once again, versatility is key. Without any need for formal adaptation, this metal-framed, wheeled system with plastic (now recycled PMMA) drawers and shelves fits just as well in offices as in kitchens, bathrooms, bedrooms, and living rooms. Mobil may be one of the first designs of its kind that doesn’t just fulfill a function, but also establishes a visual identity — defined by its function, but not by the type of space in which it’s placed.

From Fondation Cartier to domestic space, no-stop

View gallery

View gallery

Less is one of those “small architectures for interiors” through which Jean Nouvel — Pritzker-winning architect and 2022 Guest Editor of Domus — expresses his vision in industrial design. It wasn’t created for just any office, but for Nouvel’s own architectural masterpiece, the Fondation Cartier in Paris. The design echoes the building’s concept, focused on extreme lightness and immateriality. The collection includes several elements, notably a computer desk (this was the mid-90s), but it’s the table — with slender legs and a bent sheet-metal top — that became the most iconic. Thanks to its visual lightness and essential forms, which evoke an “ideal” rather than a space-specific piece of furniture, Less soon became sought-after for home use as well.

The modern icon that became the queen of all lounges

When tasked with designing the German Pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona World’s Fair, Mies didn’t just create a modernist masterpiece — he also designed the seating for the visiting Spanish royalty. Inspired by Roman folding chairs, the piece featured intersecting chrome steel legs and leather straps. In 1953, Mies allowed American company Knoll to put it into production, starting a new chapter in its story. The Barcelona Chair became the chair for corporate lobbies and executive offices — but alongside Mies’s equally iconic daybed, it also found a lasting place in domestic interiors, returning to the representative role for which it was originally conceived.

A perpetual calendar that everyone wants to have (including Gucci)

View gallery

View gallery

To this list of furnishings, we add an object — perhaps the one that most successfully transitioned from workplace tool to integral part of interior design (unlike, say, the typewriter). A full expression of Enzo Mari’s design philosophy, the Timor is almost mono-material (plastic, with PVC date cards) and fundamentally a visual project. Its fan-shaped rotating cards — displaying days, months, and years — its lettering, and the way the cards disappear into the base, all contribute to its immaterial and decorative essence. Still in production despite being functionally obsolete, Timor has found its way into every kind of environment and was even reinterpreted by Gucci for its “Ancora” campaign, a tribute to Milanese modern design.