Some series tell a story. Others tell an era.

Mrs Playmen does both, but with a third and perhaps most ambitious aim: to reconstruct the cultural atmosphere of an Italy that still lacked the language to call itself modern, that had no laws to protect women, that spoke of emancipation while fearing it at the same time.

It is within this tension that Adelina moves: a figure both luminous and tragic, a ruthless entrepreneur and a vulnerable woman. In 1970s Rome — where “feminism” was a suspect word and violence against women was not yet considered a crime against the person — Adelina builds an empire and pays for it with her own skin. And the series, with a surprisingly subtle visual sensibility, entrusts interiors and objects with the task of expressing what words cannot say.

Her penthouse is a visual manifesto: not just a place, but a declaration of intent. The bathroom lit by Antonio Pavia’s lamp — its fabric-and-brass leaf-shaped shade blooming from a shell-shaped base — is already a scene in itself: a small domestic sanctuary where femininity contemplates itself and, for a moment, escapes the male gaze. The walls clad in typical ’70s patterns, the wallpaper of brown, blue and white diamonds, the curtains of overlapping circles create a pulsating chromatic landscape — almost the heartbeat of the house.

Every lamp, every armchair, every wallpaper is a note in the grand score of Italy’s cultural transformation.

The living room, dominated by Martinelli Luce’s Cobra and Pistillo lamps and the five-arm Swedish Cottex lamp, vibrates with that Italian modernity that even today feels like an act of defiance. An egg chair evokes the utopia of futuristic design, while the soft, generous armchairs and sofas speak of a sophisticated, unconstrained comfort — as if women’s bodies, there, could finally rest without being judged.

In a backlit niche, a display case of vases seems to exhibit not objects but metaphors: fragility and power, transparency and opacity, aesthetics and use. The bar cabinet — topped by the Splügen Bräu lamp, hanging like a small industrial sun — tells of nightlife, negotiations, meetings, lovers. It is a home that speaks of a woman who wants to be the master of her own destiny and yet knows she will never fully be.

Then there is domestic life: the Grillo telephone chirping with its futurist irony, the ceramic dog as tall as a kitschy sentry, the television shaping Italy’s sentimental education through the ritual of Carosello and the child who “has to go to bed after the theme song.” An Italy rigidly codified, which Adelina tries to pry open little by little.

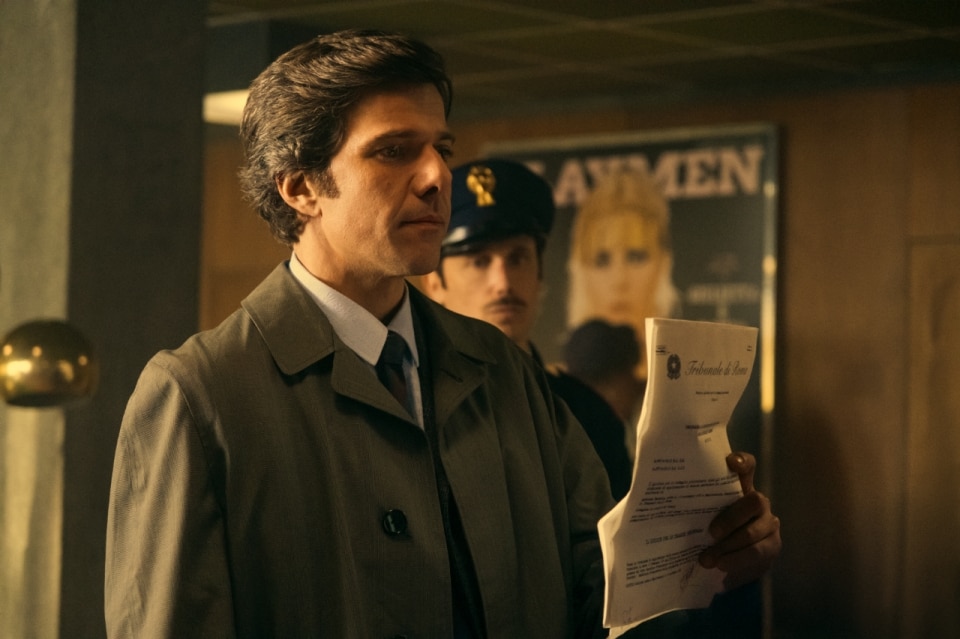

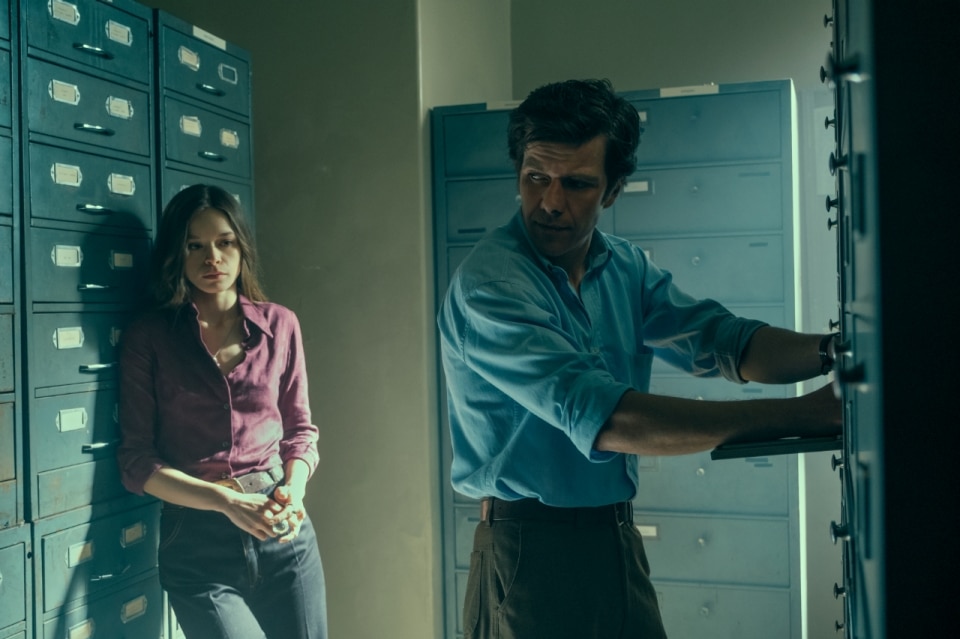

The Playmen editorial office is the visual counterpoint to the penthouse: a masculine space reinvented through a feminine gaze — Adelina’s. The large windows overlooking the dome of St. Peter’s are not just a scenic flourish: they are the perfect image of the contradiction between modern hedonism and Catholic tradition, between freedom and censorship, between body and dogma. The furnishings do the rest: the large mustard-coloured sofa with sculpted lines and brass feet at the entrance; the drafting tables, lightboxes, multicolour tunnel photo sets — all speak of an image workshop that is also a workshop of desire.

The iconic Meta lamp by Stilnovo and the totemic coat stands, with aesthetics suspended between Futurism and domestic sci-fi, illuminate a world that wants to “speak the new” while knowing it is walking a tightrope. The latticework false ceiling, the adjustable vertical-strip curtains, the laminated wood walls evoke the taste of editorial offices of the time: functional yet ambitious, a bit precarious and a bit roaring. The Yashica cameras and the Parentesi lamps point to another dimension: that of doing, trying, risking. A newsroom as a workshop of the possible — and one that even invents clandestine strategies, like when Tattilo finds a way to advertise the vibrator “Gabry, the new friend of women” without getting reported.

The series manages to portray Rome not as a postcard but as a state of mind. The historic Roman bus — with original upholstery and seats — is a steamroller of collective memory; the photographer’s Vespa, the row of red Fiat vans delivering magazines to newsstands, the convertibles and the “shark-like car” are cultural markers that reconstruct an Italy where mobility is both a promise of freedom and a metaphor for escape. The Piper and Jackie O’ recount the night: rebellion, music (the inevitable Il paradiso by Patty Pravo), the drifts of an era that still didn’t know how to name its ghosts.

The Côte d’Azur, meanwhile, is a counterpoint: the sunlit elegance that contrasts with the bleakness of the Mandrione. Adelina moves between these worlds with the same ease with which she moves from her intimate bathroom to her desk overlooking the Vatican dome: a woman who inhabits contradictions.

Mrs Playmen is not just a biographical series. It is a sensory map — an emotional reconstruction of a country approaching modernity more through collision than conviction. It is the portrait of a woman trying to carve out a space for herself between non-existent rights and irrepressible desires. And above all, it is a series where interiors do not merely furnish: they narrate.

Every lamp, every armchair, every wallpaper is a note in the grand score of Italy’s cultural transformation.

A score that Adelina, with all her limits and desperate strength, attempts to play until the final scene.

All images: Camilla Cattabriga/Netflix