There isn’t a single intention or unified plan behind the design of different series and films produced by HBO Max—or even just available on the platform. Rather, there is an idea of how their productions should be crafted. This has been evident in many successful and less successful series, from the hugely popular Westworld to the more niche Raised by Wolves: production quality is one of the very first concerns. This has a strong effect on design, which in film and television is the combination of costumes, set design, and cinematography, all coordinated around a precise visual and aesthetic concept. This happens in every film and series, but rarely do these choices express refined taste, knowledge of design history (even just recent history), or genuine care.

The titles discussed here—four series and one film—show how HBO chooses or works with interior design, costumes, or simply setting to mark differences between characters, or between characters and viewers. Design is often associated with wealth and luxury, but not all wealth is the same.

Succession

In what is one of HBO’s most famous recent series, design does not serve a spectacular function nor aim to be iconic. Instead, it builds a visual language that adheres almost mimetically to the world it portrays. The production designer is Stephen Carter and the set decorator is George DeTitta Jr., and their core idea is that extreme wealth does not need to be displayed. On the contrary, it should appear as something natural, sedimented, almost invisible to those who possess it.

This means luxurious environments that are never ostentatious, expensive but understated materials, neutral palettes, high-quality furnishings chosen to last rather than to impress. It’s the “old money” aesthetic—hereditary wealth that does not need to legitimize itself. Here, design does not explain wealth but shows how it is lived.

Apartments, offices, yachts, private jets, and boardrooms have nothing spectacular about them; they are simply functional. References include the interiors of real American dynasties such as the Murdochs, Redstones, or Bronfmans.

The Gilded Age

The Gilded Age is the opposite: spectacular ostentation, used to show the collision between money, status, and social representation. It is, of course, historical reconstruction, but of an era when architecture and furnishings were forms of public affirmation of power. Production designer Bob Shaw and set decorator Regina Graves in some cases worked with real locations—late 19th-century American residences (from Newport “summer cottages” like The Breakers and Marble House to Lyndhurst Mansion and Glenview Mansion)—while in others they rebuilt environments in the studio.

The underlying idea is to contrast the newly rich with those whose wealth spans generations, starting from how they live and what surrounds them. The new rich favor French taste, as was fashionable at the time, and bold colors, while old money families inhabit darker homes with palettes rich in browns and burgundy. Spaces that reflect worldviews—because these were years when status and political position were communicated through design.

Sex And The City

One of the most famous series ever made has the city in its title and is completely dependent on New York architecture for its tone and appeal—both indoors and outdoors.

As always, design reflects the personality of those who inhabit the spaces. Charlotte lives in bright, orderly interiors dominated by light tones and traditional materials that communicate stability and bourgeois aspiration. Samantha inhabits more open, sensual spaces built on dark materials and bold forms. Miranda chooses functional, rational, almost defensive design, made of clean lines and neutral colors.

Unlike other series, however, there is an explicit pursuit of beauty and desirability. Sex and the City is aspirational: it shows things inaccessible to many not to condemn them (as Succession does) but to idealize them. This is not New York as it really is, but a polished version selecting the best.

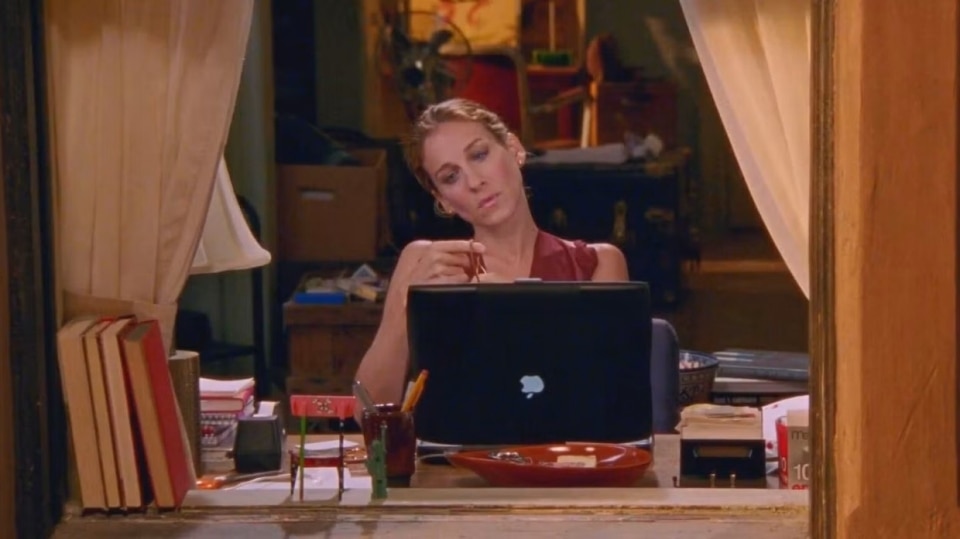

Carrie Bradshaw’s apartment in particular breaks with the typical television idea of home. It is built through accumulation—objects found at flea markets, vintage pieces, contemporary design elements, and bold color choices. It’s an apartment that grows over time with the character, enriching itself as Carrie gains experiences, relationships, and life choices.

What makes this design especially significant is its ability to normalize desire. The iconic walk-in closet, carved out of a simple corridor, is not an exhibition of unreachable luxury but a creative transformation of ordinary space. Likewise, the desk placed in front of the window, the mix of differently sized artworks, and retro seating combined without apparent coherence create an aesthetic that seems spontaneous, almost casual, while being carefully designed. It’s a design that invites emulation because it feels possible, replicable, close to the viewer’s real experience.

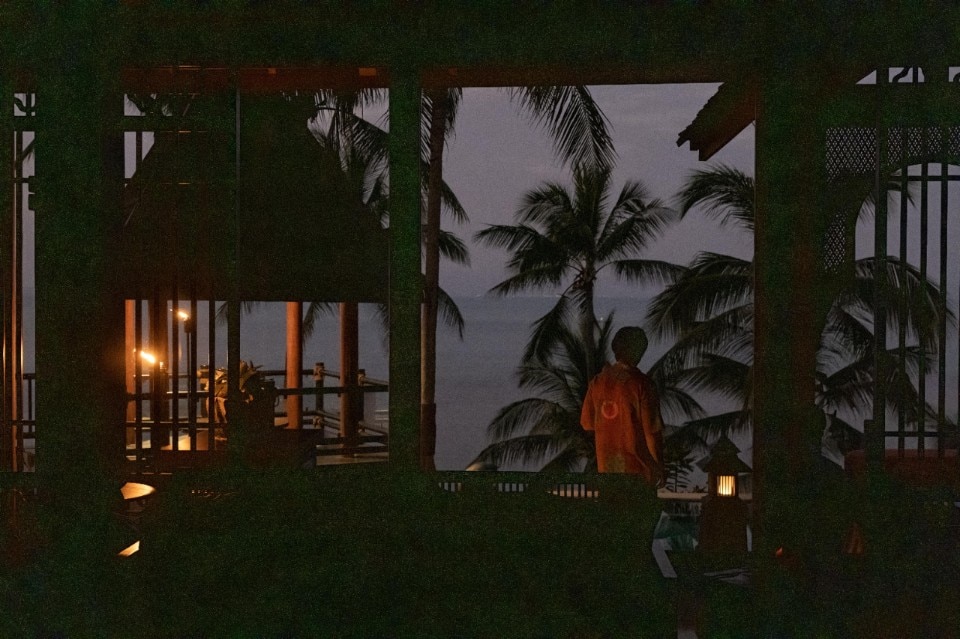

The White Lotus

What distinguishes The White Lotus from many other series set in luxury environments is its systematic use of design elements loaded with ambiguity. The hotel setting is, by definition, a space of total comfort designed to eliminate friction. The series reverses this function, turning furnishings, objects, and decorative details into narrative signals.

Iconic lamps like the Castiglioni brothers’ Arco lamp, beaded curtains, overly elaborate tableware, monumental or deliberately unpleasant bathtubs are not included for pure aesthetic pleasure but to create a constant short circuit between beauty and discomfort. Design becomes a silent commentary on what is happening on screen.

There is also a capacity to focus attention on seemingly marginal objects—a blue-and-white striped beach umbrella, a shell-shaped sugar bowl, a curtain separating two rooms—and make them meaningful. Even more interesting is how luxury is layered.

In the second season, set in Italy, international modernist design, high-end hotel furnishings, and the more traditional aesthetics of historic Sicilian villas coexist. This overlap is not neutral: it signals differences in class, cultural background, and attitudes toward money. Private villas, with wallpapered walls, galleries of paintings, and redundant decorative objects, communicate an idea of ancient, almost suffocating wealth; hotel spaces, brighter and more orderly, embody a globalized, standardized luxury designed for rapid consumption.

Here

We had already covered this film when it was released; now it’s on HBO Max, and it’s the most radical example of space as a narrative device—a nearly conceptual use of design. Here, design does not accompany the story; it is the story. Almost the entire film is seen from a single fixed point of view: the corner of a living room, across the 20th century.

Here overturns a typical convention of contemporary cinema and television: it’s not the characters who “use” the space, but the space that observes the characters. The living room functions as a kind of visual archive of American life, a time capsule in which domestic design reflects aspirations, frustrations, and social changes.

From era to era, that living room shows how styles, materials, and furniture arrangements embody the fears, enthusiasms, and ideals of their time—from 19th-century bourgeois rigor to the creative disorder of the 1920s, postwar standardization, and contemporary visual saturation. Objects carry symbolic value as well.

In Here, furniture is never neutral: a floral sofa can become the sign of a burdensome inheritance, while its replacement with a modern model tells the story of a desire for emancipation from a previous generation. The constant rearranging, moving, and renewing of domestic space becomes an explicit metaphor for the human attempt to control the passage of time and renegotiate one’s place in history.