In November 2016, less than a year from the departure of David Bowie, Sotheby’s auctioned a peculiar collection that belonged to the late artist. One hundred Memphis design objects – including statement pieces like the Carlton bookshelf and the Casablanca cabinet by Ettore Sottssass Jr., the Plaza vanity Table by Michael Graves and the Super Lamp by Martin Bedin – that highlighted Bowie’s passion for the collective of designers founded in Milan in 1981.

Today, ten years after the death of the Thin White Duke, the singer’s relationship with — and importance for — design (and not only design) is further cemented by the newly established David Bowie Centre, housed within the V&A East Storehouse in London. This vast, free-entry storage facility of the Victoria and Albert Museum was recently inaugurated in Stratford, the eastern district of the British capital redeveloped (not without questionable taste) for the 2012 Olympic Games. The centre brings together memorabilia and keepsakes, many of them obsessively catalogued over the years by Bowie himself, who meticulously annotated his belongings with handwritten Post-it notes.

A form of self-archiving that is at once philanthropic and brand-conscious, revealing an awareness of his own significance even beyond death. This is underscored by an auction catalogue in which Bowie took part in order to reacquire a tape containing an unreleased early recording.

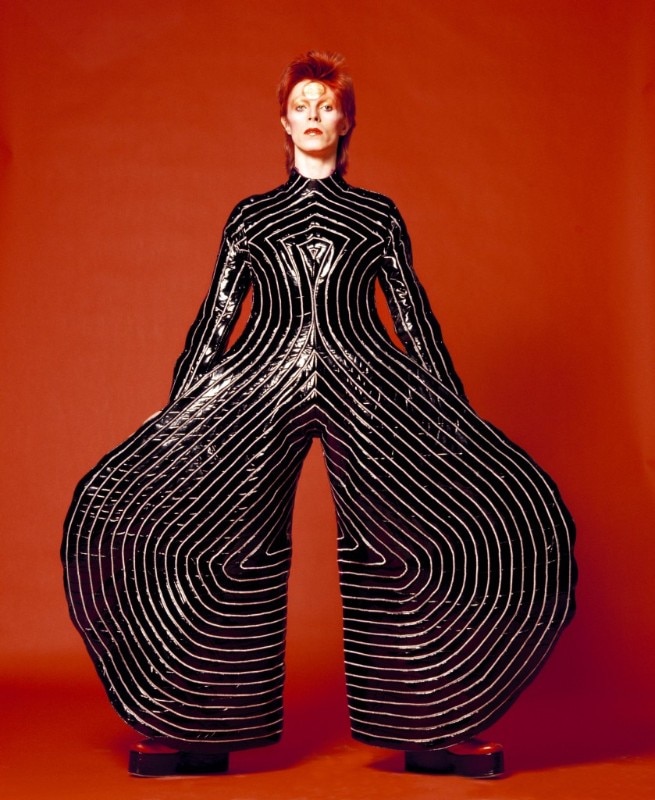

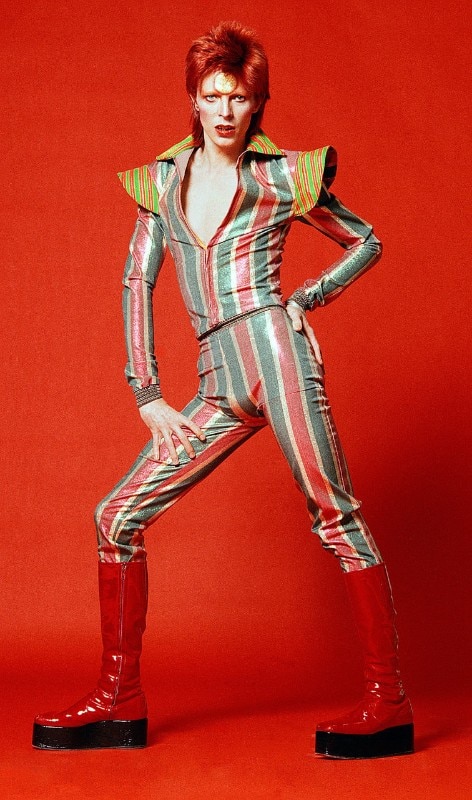

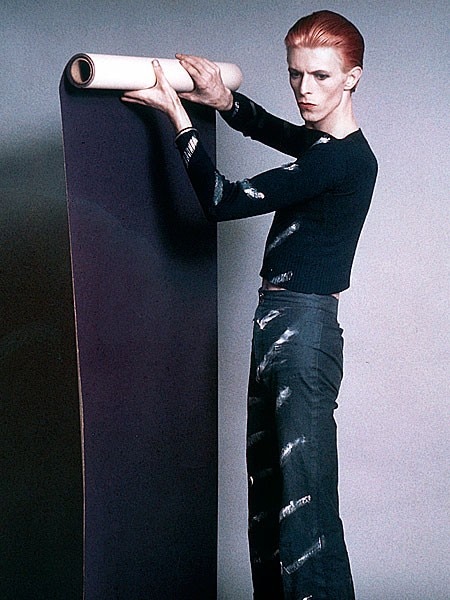

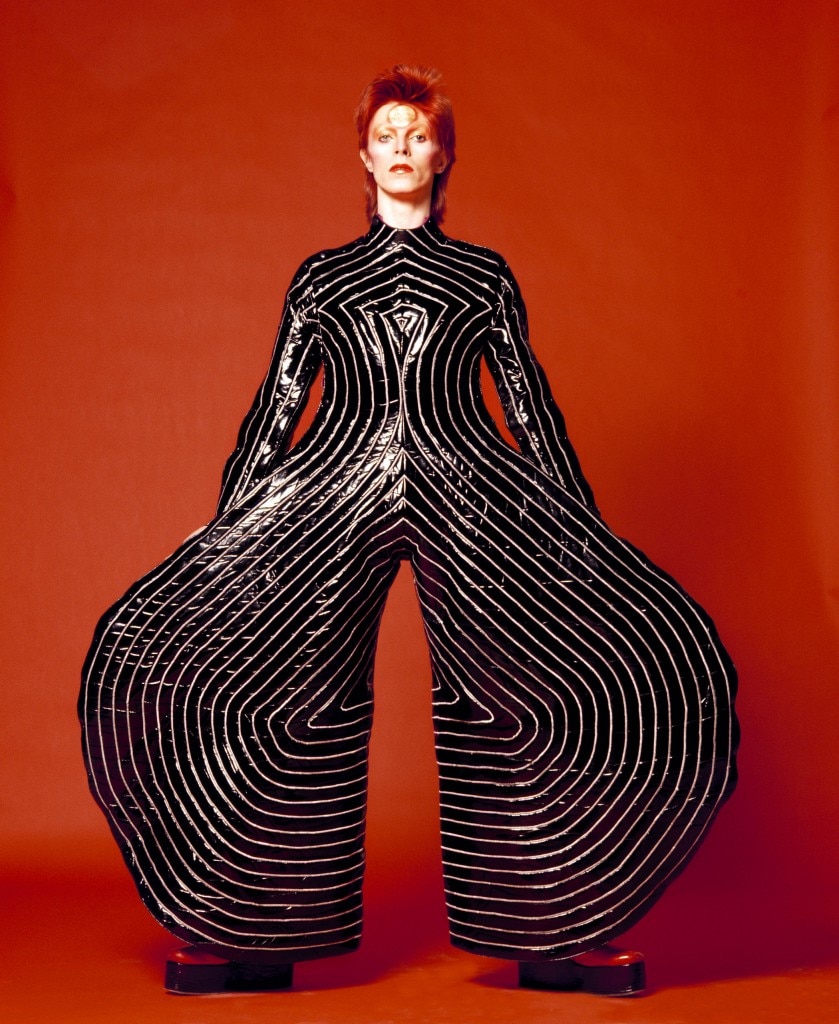

Space is therefore given to instruments — such as the EMI Synthi AKS synthesiser used with Brian Eno to record “Heroes” — as well as to the most varied ephemera, from a Ziggy Stardust Barbie doll to concert setlists. Costumes are of course present too, including the suede bodysuit designed in 1971 by Kansai Yamamoto — one of the designers Bowie collaborated with most closely — for a Ziggy Stardust live performance, later worn by Kate Moss at the 2014 Brit Awards.

An iconographic legacy that goes far beyond fandom and now becomes part of Britain’s cultural heritage, freely accessible to the public through “one-to-one” sessions with their object of choice. Visitors can thus spend an hour studying the types of make-up Bowie used on the Station to Station tour (1976), or reading the letters sent to him by fans.

Modernism at the roots of the Bowie myth

Born David Robert Jones in Brixton, South London, in 1947, Bowie manifested an interest for the world of arts even before picking up his first instruments. When studying art, music, and design at the Bromley Technical High School, David fell in love with jazz and blues, therefore, with their modernist artworks. On one hand modernism as the current permeating the design and the architecture of the times, on the other as the Mod subculture the young Bowie adhered to, were pivotal in forging his artistic sensibility, soon coming to life in the total art of his albums, videos, costumes and performances.

It is with this modernist attitude that Bowie led the evolution of popular culture, reading the changing spirit of times like an open book and embodying it before it turned into fashion, actually defining it.

The artworks of Bowie’s albums, just like their content, or, more simply, his ever-evolving face, became the map of fifty years of Western design and pop culture. Bowie moved seamlessly and at ease across genres and subcultures, spanning from the rhythm and blues of early ‘60s London to the Jungle of the late ‘90s, and encompassing psychedelia, glam, “plastic soul”, new wave and new romantic along the way.

The total art of the alter-egos

The hippy performances and the theatre practices between the commercial failure of the first singles and the breakthrough of the 1970s are therefore fundamental in tracing the aesthetics and the total art that characterise the entire career of Bowie.

Thanks to the experience of the Art Labs – a movement formed in 1968 in the English capital, which influenced many likeminded mixed arts workshops across Europe, including the London ICA (Institute of Contemporary Arts) – which he also promoted in the town of Beckenham, Kent, Bowie developed the mindset resulting in the staging of a plethora of alter-egos. Their birth and death are summoned by Bowie himself, not as a tantrum, but as a necessity generated by the changing cultural season.

I’m Pierrot. I’m Everyman. I’m using myself as a canvas and trying to paint the truth of our time on it.

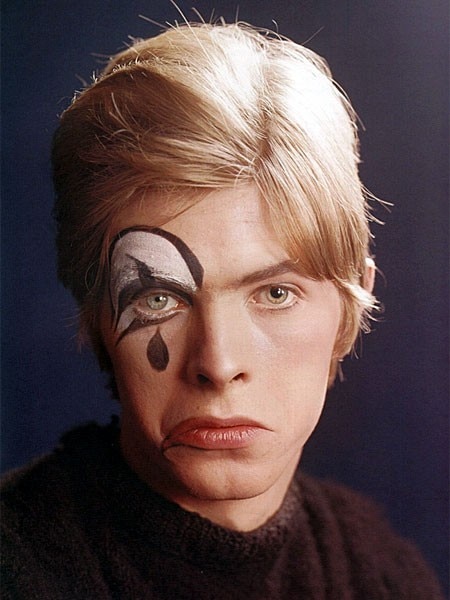

Bowie made this clear in a 1976 interview for the Daily Express: “I’m Pierrot. I’m Everyman. What I’m doing is theatre and only theatre […] I’m using myself as a canvas and trying to paint the truth of our time on it.”

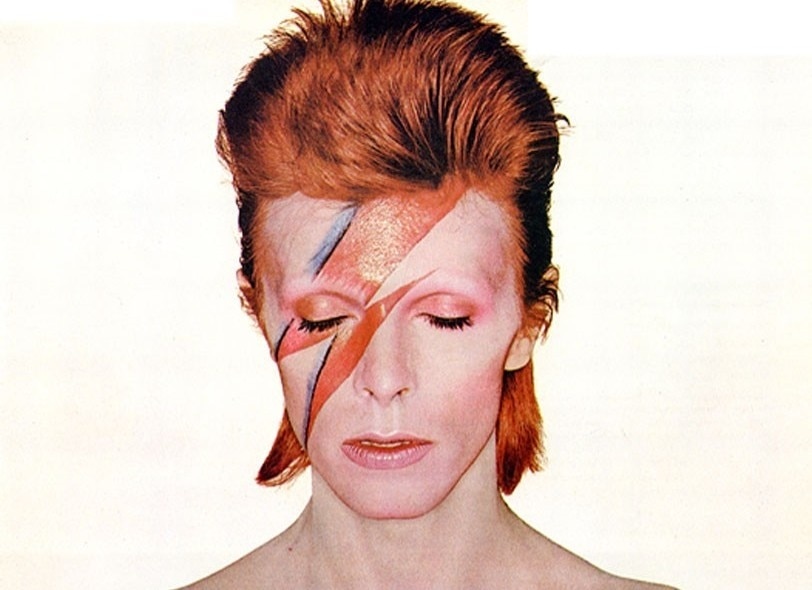

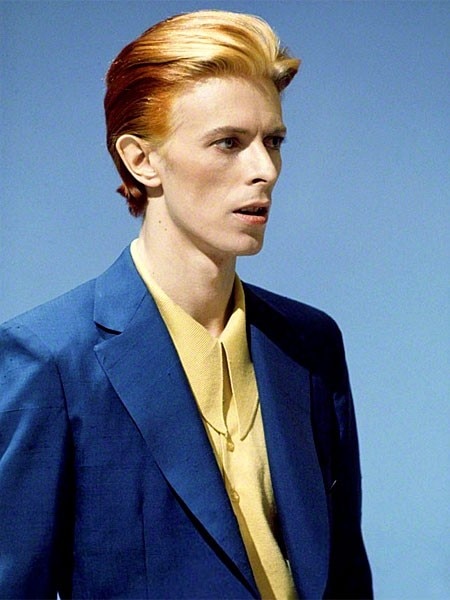

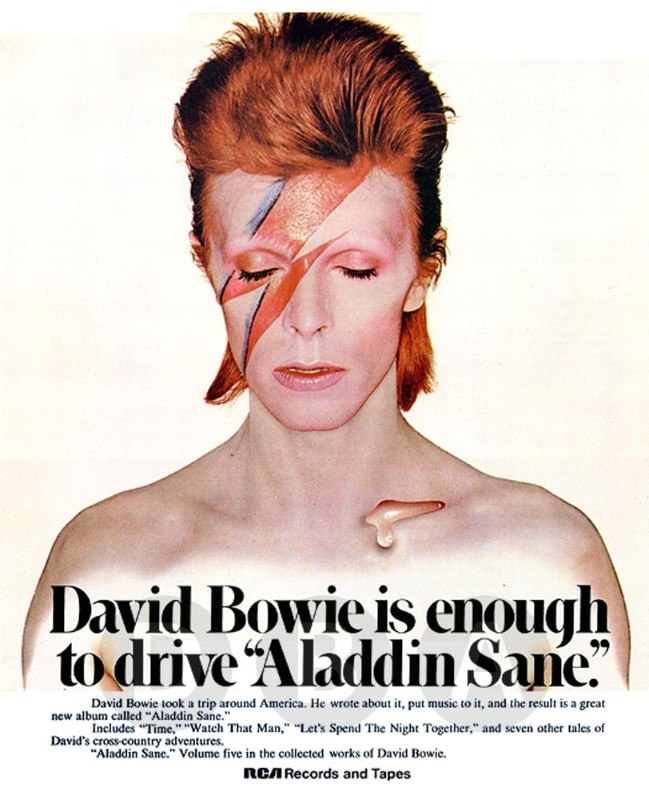

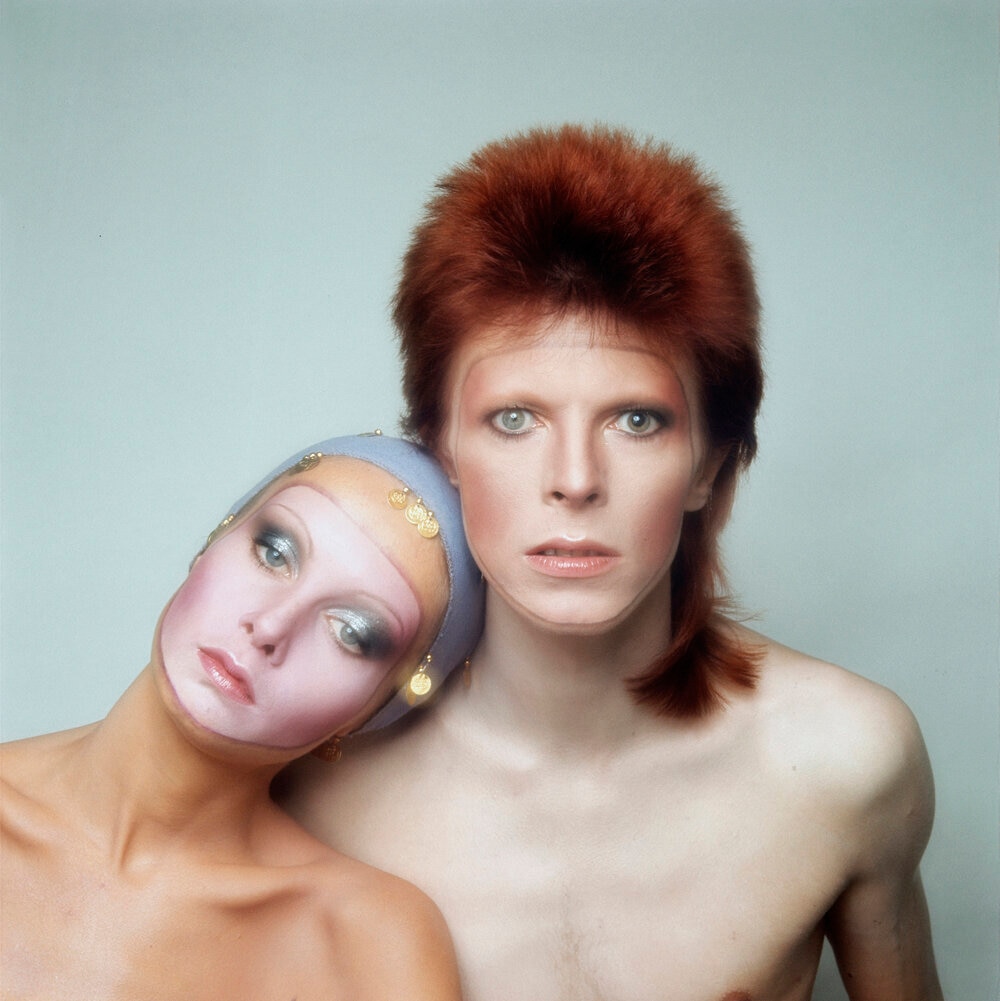

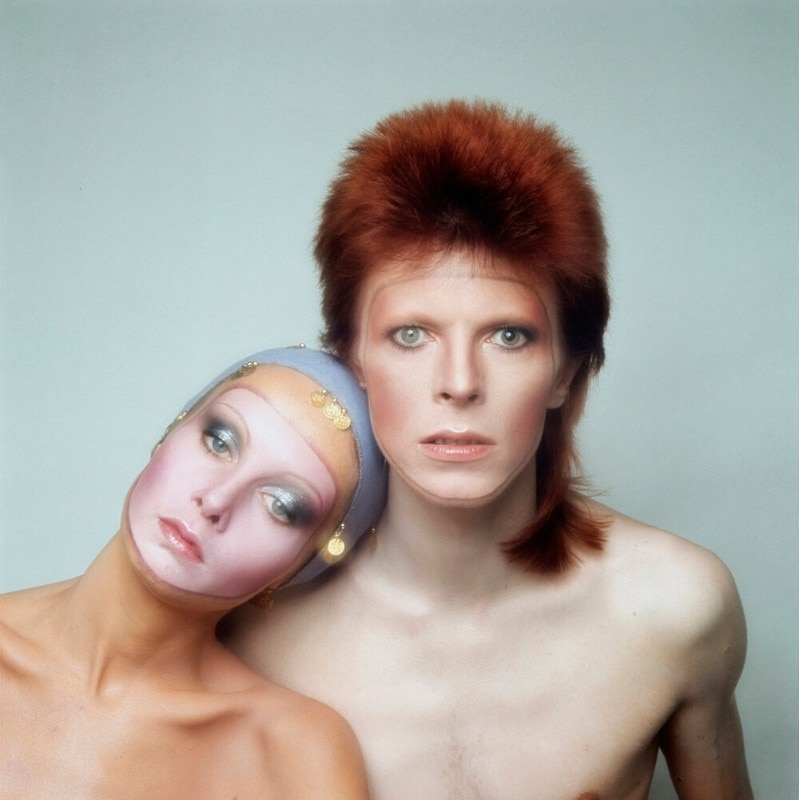

In doing so Bowie surrounded himself with artists, designers and tailors like Freddie Burretti, who crafted the ice blue suit used in the Life On Mars? video and the mustard one immortalised by the camera of Terry O’Neil. It was another maestro of British photography, Brian Duffy, to capture the role played by make-up in Bowie’s aesthetics with his portrait adopted for the timeless artwork of Aladdin Sane.

Then, there is the collaboration with Alexander McQueen, with whom Bowie co-designed the Union Jack-patterned coat – an “anti-icon” – protagonist of Earthling, the 1997 album representing one of the experimental peaks in the artist’s career. An LP where, despite his fifty years of age, Bowie felt the need of documenting what, back then, was the new drum and bass phenomenon.

Impossible not to mention the pierrot costume by Natasha Korniloff for the 1980 Ashes to Ashes video, a glammed-up tribute to the mimes that had fascinated the young Bowie of the 1960s when, still a folk singer-songwriter, he posed for the camera with his face embellished by white make-up and a black tear.

However, it’s the collaboration with Japanese designer Kansai Yamamoto to stand out. With the costumes used for the Aladdin Sane Tour of 1973 Bowie was among the first artists to reveal the necessary relationship between music and fashion design. Yamamoto’s creations, with their hyperbolic silhouettes are perfect for representing the glam and theatrical extravagance of Bowie-Aladdin Sane.

These costumes, inspired by those of the Bauhaus theatre, highlight the importance represented by the past – from the Weimar School to the commedia dell’arte and the pop icons of the youth – as a prerogative to shape the present.

A love for Memphis

Bowie’s theatricality — enigmatic, playful, and layered with references that move freely between high and low culture — inevitably echoes the disorienting artistic freedom embodied by the Memphis group in the early 1980s. Just as Memphis designers transformed luxury furniture into playful, accessible divertissements of form and colour, Bowie was a deep and refined intellectual who was never elitist. A postmodern design language for a visionary who managed to become the demiurge of a new — indeed future-oriented — modernity, without ever losing sight of his cultural roots.

The group’s very name, in fact, winked at Bob Dylan and his Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again — a song beloved by Ettore Sottsass’s Beatnik youth and equally cherished by Bowie. It is hardly surprising, then, that the visions of Sottsass & co. would align so closely with Bowie’s tastes: Bowie himself paid homage to Dylan by dedicating the title of a song on his first successful LP, Hunky Dory, to him.

What Bowie admired about Memphis was its ability to create extraordinarily innovative pieces while reclaiming retro, outmoded materials such as Formica, plastic laminates, and briarwood. In a 2009 interview with GQ, seated beside his beloved Palm Springs table by Sottsass, he remarked: “As a kid, I spent an incredible amount of time reading and drawing at the living-room table, just like this one. […] The table is by the wonderfully original Milanese design group Memphis; it’s probably made of hardboard and old socks.”

Stage design and album artworks to envision the future

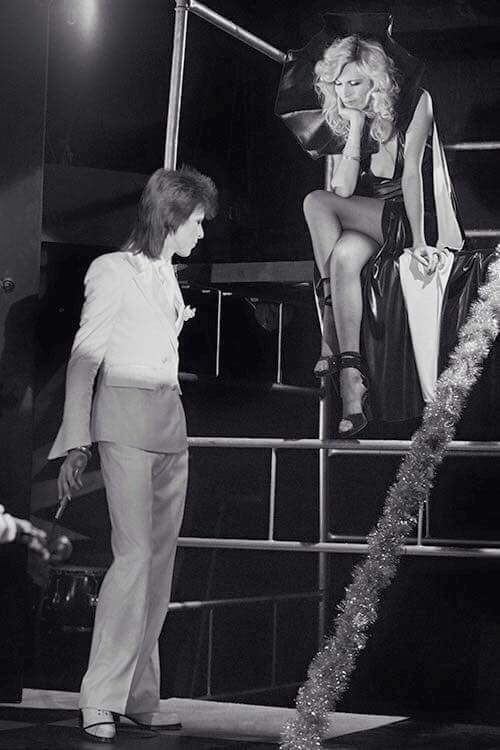

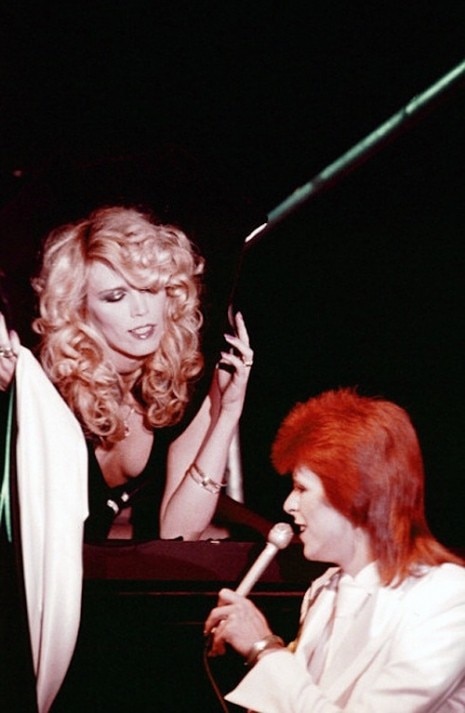

The stage is the inevitable site where Bowie applies the continuous creation and destruction of new cultural seasons. Take the urban, asphyxiating and dystopian one designed for the Diamond Dogs Tour (1974) to resemble a representation of the scenarios of George Orwell’s 1984. Or, the human checkboard adopted for the 1980 Floor Show, a TV special aired in 1973 where Bowie brings to life his vision of the future by covering a song old of nearly ten years (Sorrow by The McCoys) while quoting, in a whirlwind of sexual tension, Alice in Wonderland in conversation with the androgynous muse Amanda Lear.

1980 Floor Show (1973)

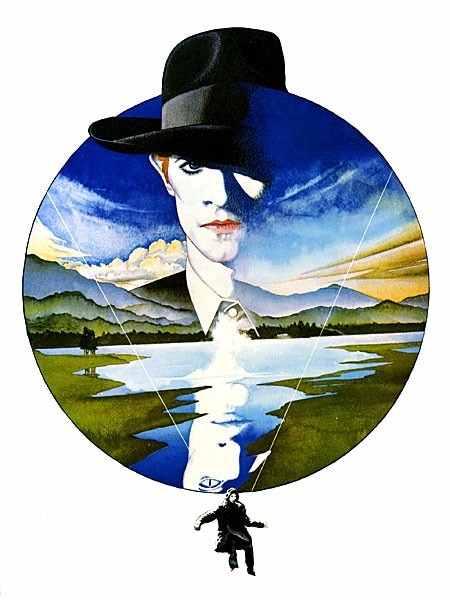

Not to forget the films starring Bowie. On one hand the alien and alienating set design for The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), on the other those for Labyrinth (1980) by Jim Henson – the puppeteer father of The Muppet Show – where homage is paid to the impossible architectures of Escher and Piranesi.

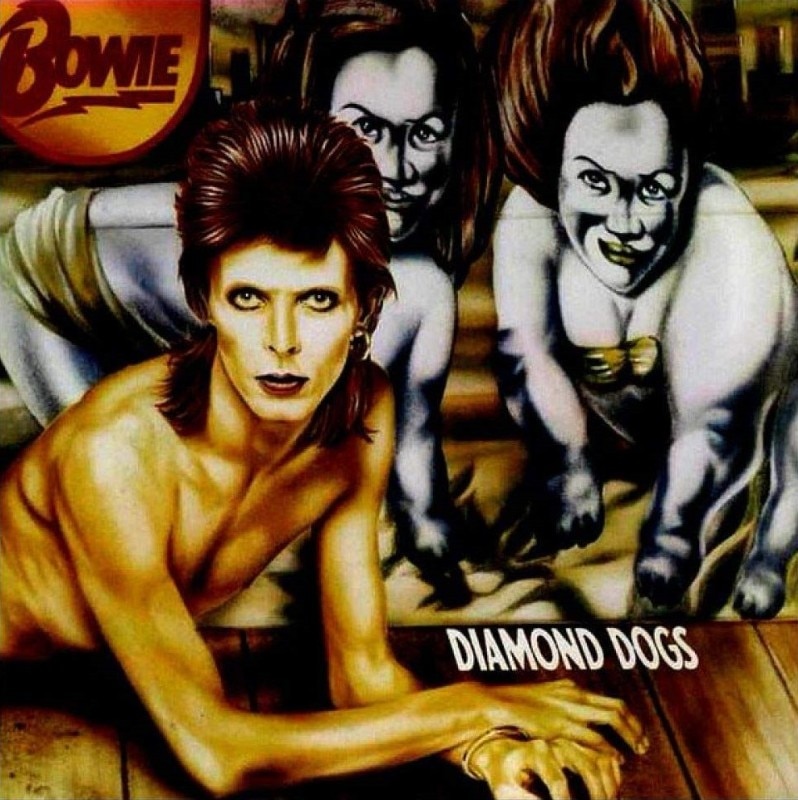

Offering a visual representation of Bowie’s vision of contemporary society and on the state of the arts are the covers of his albums too. Take the glam cyborgs with make-up by Barbara Daly of Pin Ups (1973), where David, at least conceptually, anticipates the dawn of Punk, and the zoomorphic, half man-half dog Bowie of the artwork of Diamond Dogs (1974) by Guy Peellaert – the Belgian illustrator who had already given birth to the countercultural comic Pravda and had worked on the interiors of Paris cult night club Crazy Horse.

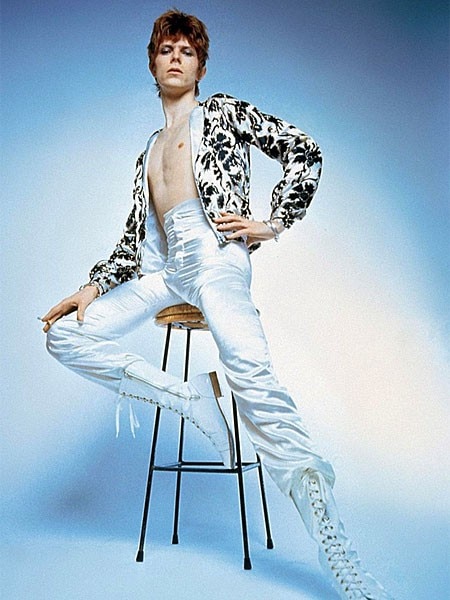

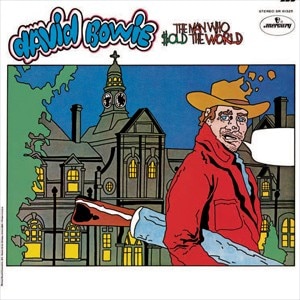

But also the importance of Pop Art and of the Art Labs experience in the original artwork for the US release of The Man Who Sold The World (1971) by Michael J. Weller, as well as the album’s new cover featuring Bowie posing in a Mr Fish dress inspired by pre-raphaelite paintings.

Or his more recent collaboration, since 2002, with Jonathan Barnbrook who, among others, conceived the artwork for The Next Day (2013), by readapting and ironically altering the cover of Bowie’s classic album Heroes.

It was Barnbrook, again, to design the visual identity of Blackstar, Bowie’s last opus and final coup de theatre, unexpectedly released in January 2016 on the day of his 69th birthday and just a few days ahead of his departure. The packaging is a gem of symbolism, containing hidden allusions to the artist’s terminal condition and able to reflect, according to the light it gets exposed to, images of stars and constellations. The final salute of the Starman to his audience.

Bowie’s eternal return

David Bowie’s practice of sacrificing his alter-egos to the altar of pop culture has nonetheless contributed to their immortality. As a consequence, pop culture itself has been absorbing his genius, repeatedly taking the late musician as a source of inspiration. From fashion collections to works of art and graphic design, the footprint of Ziggy Stardust or of the Thin White Duke is always there, in a continuous postmodern pastiche of references.

Think of the time when, just a couple years ago, Italian rapper-turned-pop star Achille Lauro stormed the Sanremo Festival stage on prime-time television with a Gucci suit simultaneously tributing the Life On Mars? And Ziggy Stardust-era Bowie. The same Italian fashion house under the creative direction of Alessandro Michele had already nodded to Bowie in their 2018 Gucci Cruise campaign Roman Rhapsody, when a series of personalities, including singer-songwriter Lucio Corsi, were filmed interpreting Rebel Rebel on karaoke.

Also think to the influence of Bowie on fashion designers such as Pam Hogg, Raf Simons (Dior SS15), Jean Paul Gaultier (SS13), Miuccia Prada (Miu Miu AW12), and John Galliano (Maison Margiela SS16), to mention a few.

Six years on from his death, Bowie’s pioneering androgynous aesthetics perhaps are his most influential heredity, another sign of the ability of the Man who fell on Earth to intercept and anticipate generational trends and shifts in culture.