The vast and complex world of gaming has always loved turning real cities into alternate worlds. Existing metropolises become settings to cross or destroy: London is the home of Assassin’s Creed Syndicate, while revolutionary Paris is that of Unity. Tokyo becomes an eerie stage in Ghostwire, and New York serves as the ‘home’ of Insomniac’s Spider-Man series for PlayStation. Then there is the unique universe of Grand Theft Auto, with GTA V set in Los Santos, the fictional city inspired by Los Angeles and even featured in a documentary. GTA VI will not be released before 2026, and the setting will be Miami. There are even rumors that actual, existing architecture might appear in the game—officially, without alterations or fictional names.

What about Milan? It has rarely had a place in video games. However, it immediately takes on a central role in Stonemachia, the new action souls-like developed by the independent Italian team Crossfall games. Milan is the matrix from which the game itself is born, along with the bizarre, and seemingly senseless, idea that the main character could be a fighting chess piece.

The setting is Medhelan, a twisted version of Milan

“The original idea was to recreate Milan,” says Ivan Maestri, head of the game’s development team, “with a strong focus on its architectural history, but in a particularly distorted version.” In fact, the main character—literally a chess piece whose design becomes increasingly complex as you level up—fights against the vedovelle (the historic 19th-century drinking fountains of Milan) and find itself in Piazza Duomo with the cathedral as a stunning backdrop, or in a ‘reimagined’ Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, and even at the Sforza Castle.

However, over time, Milan became only a part of the setting, retaining the name Medhelan, the city’s ancient Celtic name. “This project was born during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the ‘red zone’ restrictions prevented people from moving freely, which is why it was initially set only in Milan,” Ivan Maestri explains. “Then, once we were able to move freely again, the project changed and opened up to the world.”

Thus, as players move from one level to another, architectural landmarks from all over Italy appear: the Siena Cathedral, the Baptistery in Piazza dei Miracoli in Pisa, as well as a small church spotted along the Cammino del Viandante and buildings inspired by Venice. Even art has been included in the video game, as demonstrated by an entire setting recreated within Perugino’s most famous work, The Delivery of the Keys located in the Sistine Chapel.

Not everything is reproduced exactly as it is—in fact, as often happens in gaming, the architecture is made up of references that can be manipulated and transformed as needed, while remaining perfectly recognizable. “The Milan Cathedral is probably the most important landmark, but it was designed with an extra row of windows to better suit players’ visual perception,” Maestri reveals to Domus. The Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, set between two Gothic-style buildings, unexpectedly touched the water, as if you suddenly found yourself in the Venetian lagoon (or on Milan’s Navigli), and frames the Sforza Castle in the distance.

“This is the beauty of designing a video game: you can create a tower that rises endlessly, a building suspended upside down in mid-air, and all the impossible things you can imagine, leaving room for even the most unlikely combinations”—like a Surrealist painting or, going back in time, a work by Pieter Bruegel, whose famous Tower of Babel also appears in the game in digital form.

Stonemachia is also a chess game, but not quite

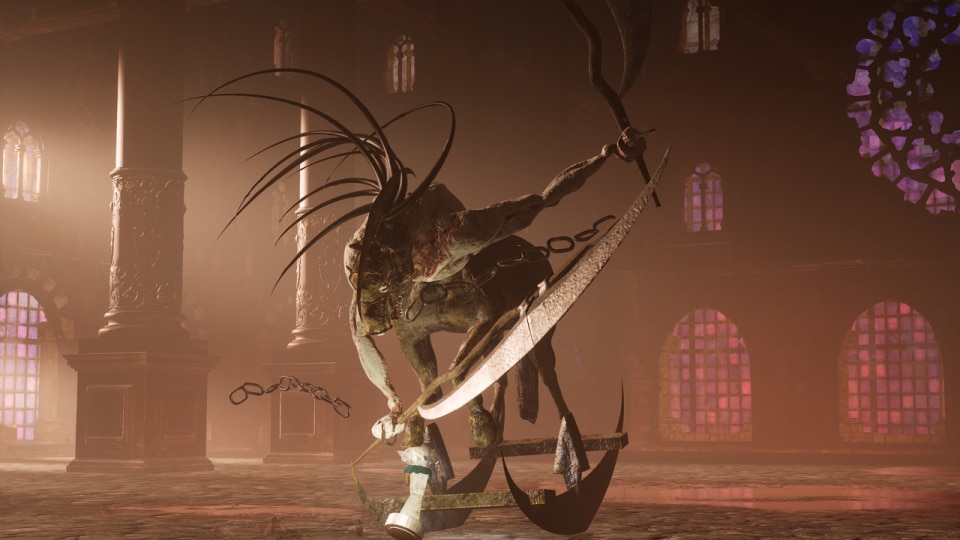

At first glance, Stonemachia looks like a souls-like set in a sequence of metaphysical locations made of stone and historical references. At every step you fight, dodge attacks, and endure, but the main character is, inadvertently, a chess piece. You start as a Pawn, then earn the power to become a Rook, Knight, and Bishop. “It’s a sort of ‘action chess’—very action, and barely chess, to be honest,” the developers say.

As the game develops, the character’s design becomes increasingly elaborate, taking on Baroque and Gothic forms, like the Rook, which turns into a real moving cathedral. “At first, we chose chess simply because of technical limitations: animating legs in 3D is anything but simple,” says Ivan Maestri, explaining how the team managed to turn the technical limitations of a young studio into a truly outlandish idea.

But what is the goal? To reach something higher, “the divine,” they say, without wanting to reveal too much—just as they did not want to spoil the appearance of the queen even during Join the Indie 2025 in Milan, where they presented the game.

Stonemachia encourages players to reflect on what it means to ascend, to evolve, to build—and who truly benefits from all of this. Around the protagonist, stone enemies and creatures known as ‘mammals’ move: these beings represent humanity itself, whose only purpose is to endlessly build the very same world in which the battles unfold.

A community that builds (almost) as much as the characters

The creation of Stonemachia’s world was not solely the work of the developers. Through social media, the team maintained a direct dialogue with those who had been following the project since its earliest mockups. “We wanted it to be clear that behind Stonemachia there are just ordinary people like us,” they say. In fact, the game’s feed is full of memes about the game itself—an appreciated humor that helped the team earn goodwill (and followers) even before the game’s release.

What’s more, a genuine community seems to have formed: daily messages—comments, DMs, reactions—suggested many of the architectural elements that now populate the game.

“There were people who wrote to us asking for a church, a village, a tower from their hometown. And sometimes, we made it happen.” And so, the project grew even further. The Bell Tower of Santa Maria Assunta in Parma, the Scaligero Castle of Sirmione, and many other important examples of Italian architecture from various eras were added.

In the end, Stonemachia is a video game that is also, in its own way, about building. The characters do it—the ‘mammals’ who frantically erect structures without any apparent purpose. The protagonist does it, evolving and building his own form to climb ever higher. And the creators do it too, who, starting from an unreal Milan, went on to design an entire animated stone world—hence the name Stonemachia—drawing inspiration from the rich history of Italian architecture.