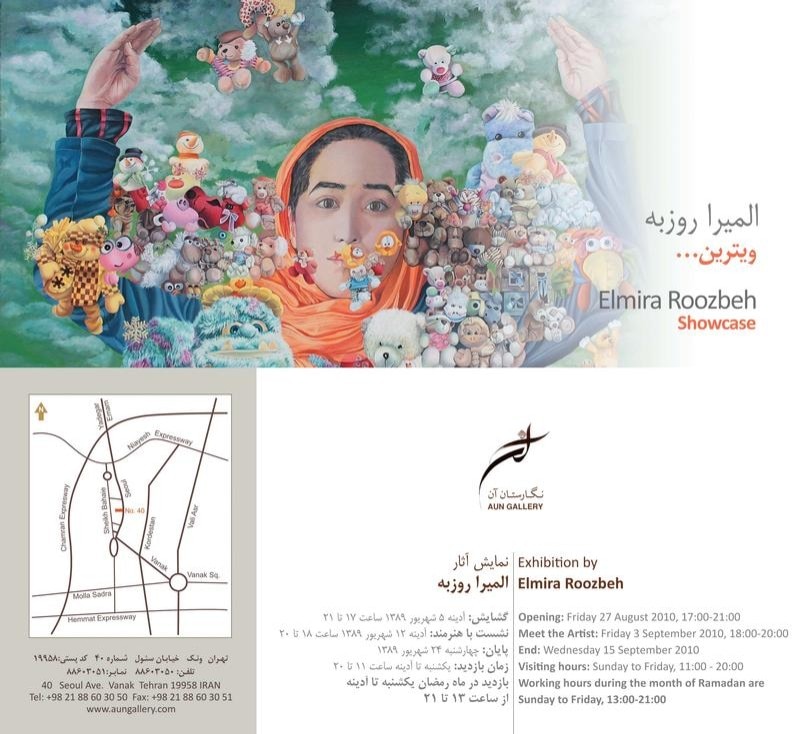

Elmira Roozbeh paints the still life, with that exception that her subject matter is not the fruit bowl, or the vase of country flowers or the dead fish on the chopping board. In an obvious contradiction in terms, Roozbeh’s still lives are about childhood. Her latest series, entitled "Show window" offers a new and disturbing look into the experiences of the child, with inevitable parallels into adulthood.

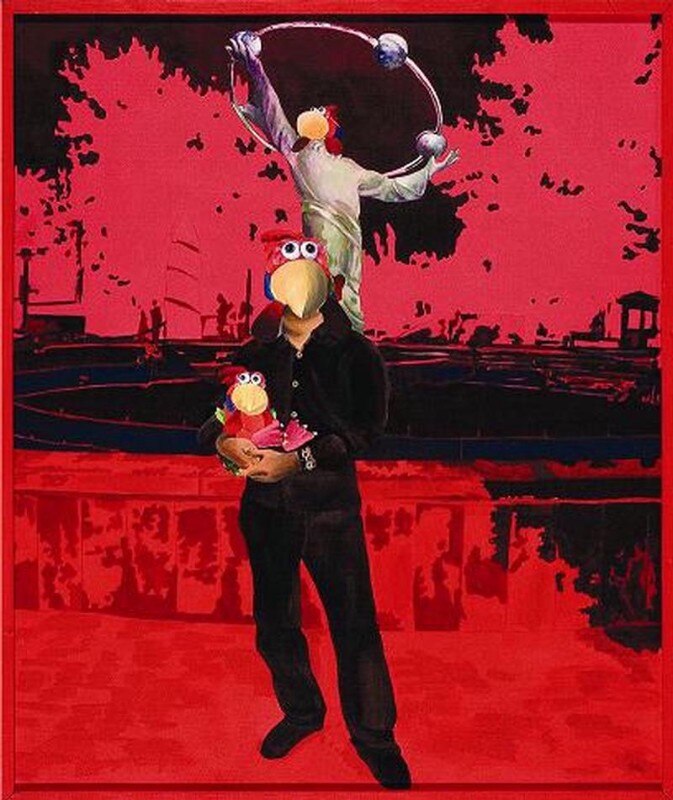

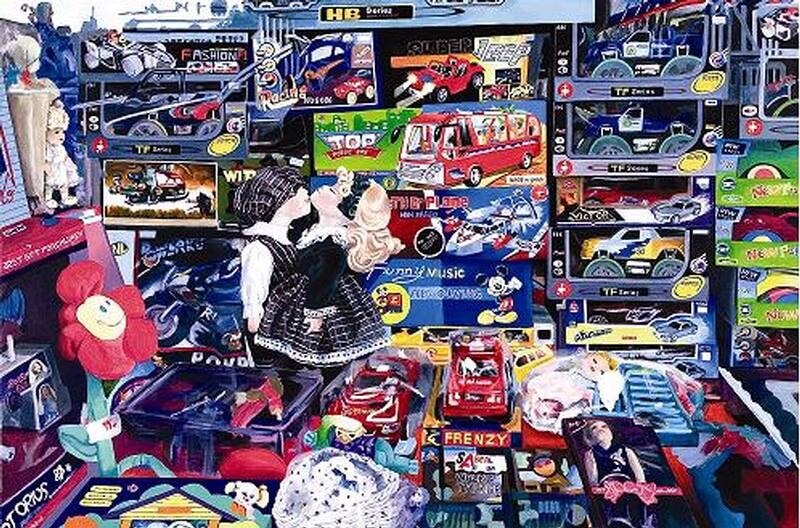

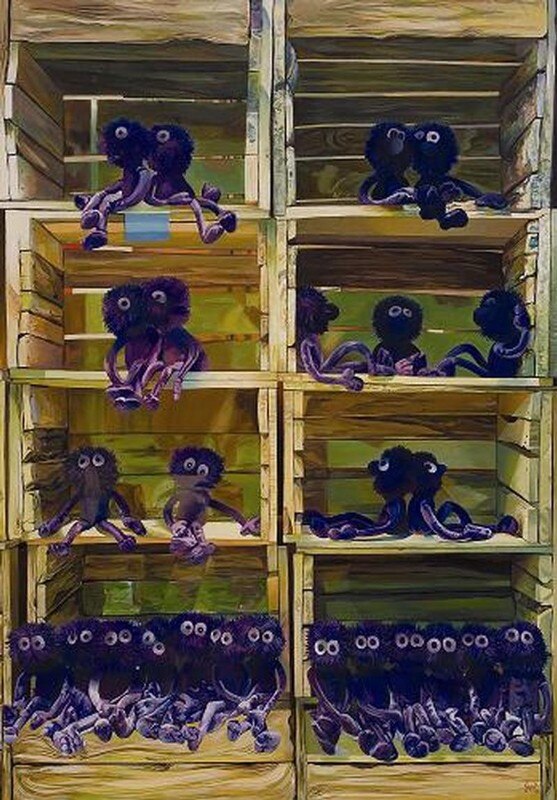

Her paintings place us on the pavement outside a toy store, peering into the shop from behind the glass window. What we see inside is a picture-perfect depiction of the ultimate toy store: shelves upon shelves of everything a child could ever dream of. But the glass window, an obstacle highlighted in the exhibition's title, and the frigid pose of the toys cast behind it seem to make a mockery of the very desire they are meant to provoke. Roozbeh’s toy store universe appears frozen in time, lifeless, airless, a sanitary perimeter where childhood is held captive. She depicts objects of play but never the child or the act of playing and thus portrays a childhood bereft of its own qualifiers. Childhood is shown as an intensely paradoxical and ultimately dismal experience, a closed universe where the child (invisible) and the toy (over-present) stare back at each other in a sterile non-interaction. With the toy inaccessible to the child, and the onlooker’s gaze obstructed by glass, Roozbeh creates two mutually exclusive worlds and introduces the concept of want and its pendant, the impossibility of want. Aspirations, in other words, are not met in Roozbeh’s paintings and children in her world don’t ever play with the toys of their fantasy. With subtle irony, Roozbeh’s paintings seem to ask us: what is it that we really long for? Is it the inert object, or is it the game, the interaction, the human touch? And what do we, the adult viewers, spend years pointlessly longing for?

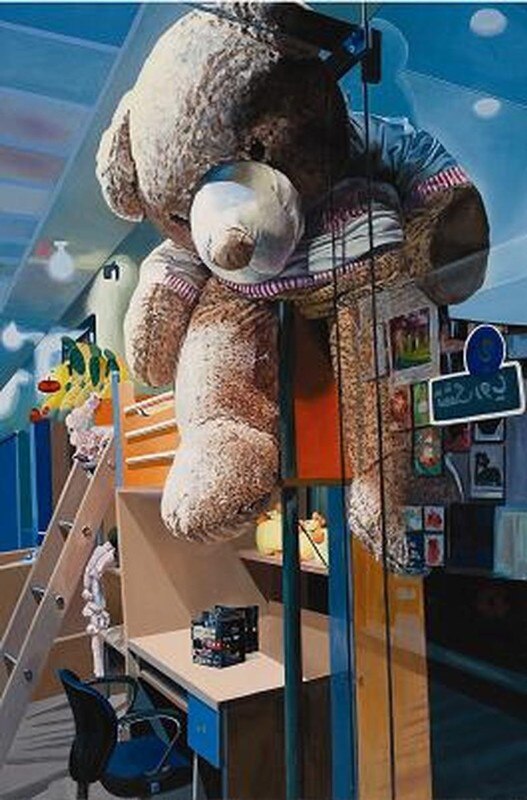

Roozbeh’s stuffed animals and dolls also act as vectors to convey or enact social taboos. In one painting, two dolls are kissing, while various packages around them spell out the words "music", "frenzy","fashion", "racing" and "high speed", all evocative of youth, experimentation and a will to be free. By transposing emotions – both figuratively and literally – onto toys and plastic wrappings, Roozbeh comments on the power of taboos in turning human beings into frozen dolls. Roozbeh’s technique borrows from exaggeration and perfectionism. With minute attention to detail and a realist technique that approaches hyperrealism in places, Roozbeh carbon copies objects – not humans or acts. Yet her depictions of over-crowded display windows and over-sized stuffed animals are much more than a perfect accomplishment in rendering; they speak of a childhood so overbearing that it cannot be surpassed. Playing, indeed toying with the concept of proportionality, Roozbeh addresses the arrested development of a generation of children frustrated by the misplaced expectations of adults. The perfect lay-out on the shelves evoke themes of orderliness and organization foreign to childhood, but very much a feature of adult life, a comment on how adult-imposed order serves only to asphyxiate the creativity and spontaneity in children. Roozbeh’s perfect execution in drawing and painting, reminiscent of a child eager to please, is itself a commentary on the absurdity of established standards of perfection.

On show at Aun Gallery, Tehran until Wednesday 15 September 2010.