Everything was growing, expanding, in 1950s Milan: the city itself with new population ceaselessly pouring into a bustling industry, but also research on construction and design, driven by a booming building market. New neighborhoods required new epicenters, still represented by places of worship in the Italian context of those years, and so it was that in Baranzate, northern outskirts of the city, today behind the Expo site, a new church was designed, where two relevant Milanese professionals, Angelo Mangiarotti and Bruno Morassutti, teamed up with engineer Aldo Favini to develop a concept of architecture for spirituality that could almost be called futuristic, as it anticipated a multitude of themes: an open liturgical space years before the reforms of the Second Vatican Council; a structure free of intermediate pillars characterized by iconic prestressed concrete beams – patented by Favini – made of X-shaped ashlars; the translucency of the envelope that visually and perceptually bound the inside with the outside, letting in nature and the city and giving back a luminous landmark for day and night, anticipating research such as Tadao Ando’s for the Church of Light, or Steven Holl’s in the chapel for Seattle University.

It soon became a cult building even in the pagan sense, i.e., a cult for the international history of modern architecture, valorized and restored across almost a decade to reopen in 2014. Domus featured it in the aftermath of its opening, on issue 351, February 1959.

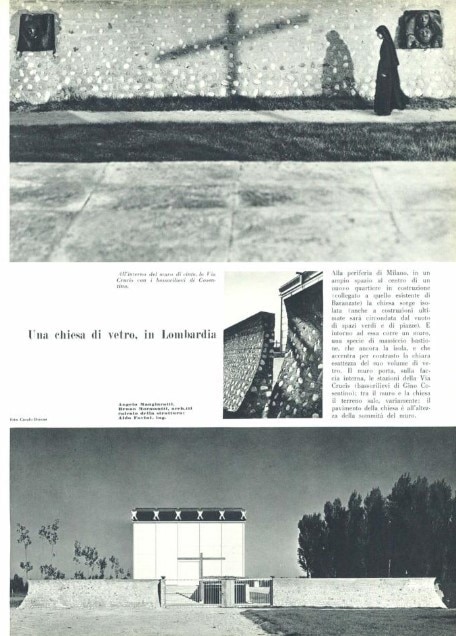

A glass church, in Lombardy

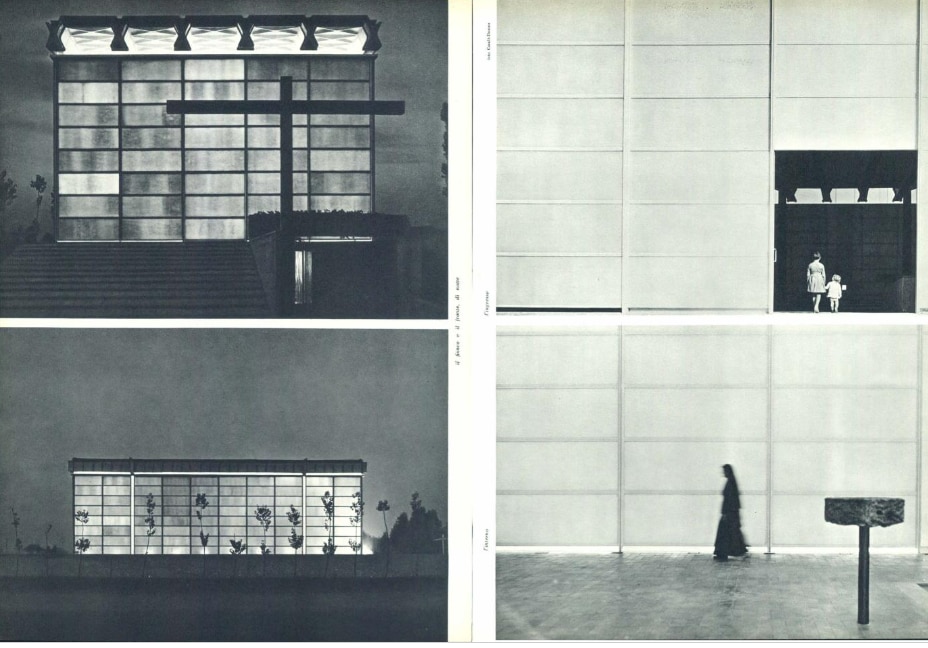

On the outskirts of Milan, in a large space at the center of a new developing neighborhood (connected to the existing ones in Baranzate) the church stands isolated (even when construction is completed it will be surrounded by the void of green spaces and squares). A wall is running all around, a kind of massive rampart, generating further isolation, and accentuating by contrast the clear exactness of its glass volume. The wall bears, on its inner face, the Stations of the Cross (bas-reliefs by Gino Cosentino); between the wall and the church the ground rises, variously: the floor of the church is at the height of the top of the wall.

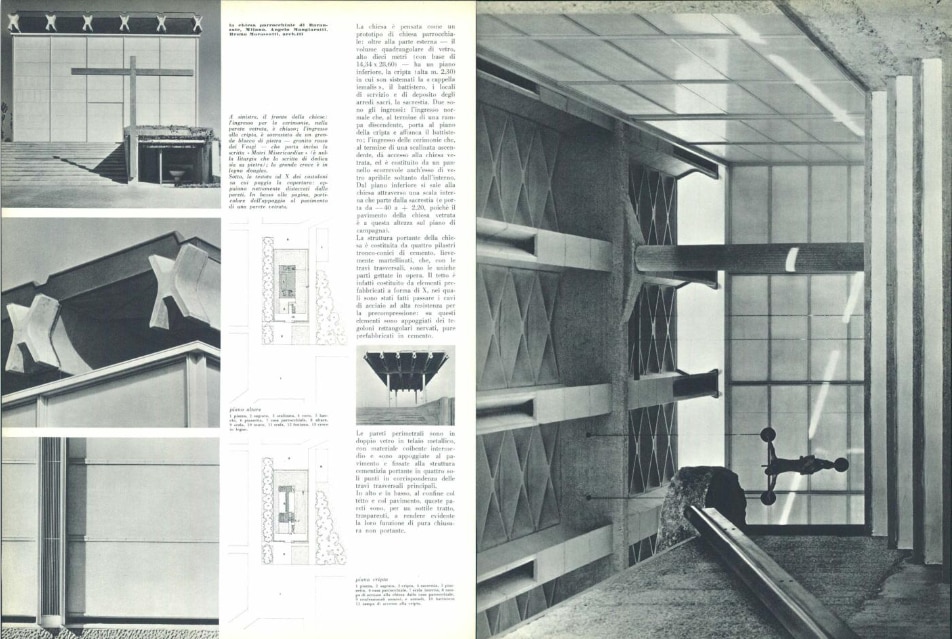

The building is conceived as a prototype for a parish church: in addition to the external part – the quadrangular glass volume, ten meters high (with a base of 14.34 x 28.60 m) – it has a lower floor, the crypt (2.30 m high) in which the winter chapel, the baptistery, the service and storage rooms for sacred furnishings, and the sacristy are housed.

There are two entrances: the normal entrance, which, at the end of a descending ramp, leads to the crypt floor and flanks the baptistery; and the ceremonial entrance, which, at the end of an ascending staircase, gives access to the glazed church, and consists of a sliding panel also made of glass that can be opened only from the inside. From the lower floor one ascends to the church via an interior staircase that starts from the sacristy (and leads from -0.40 to + 2.20 m, since the floor of the glass church is at this height above ground level).

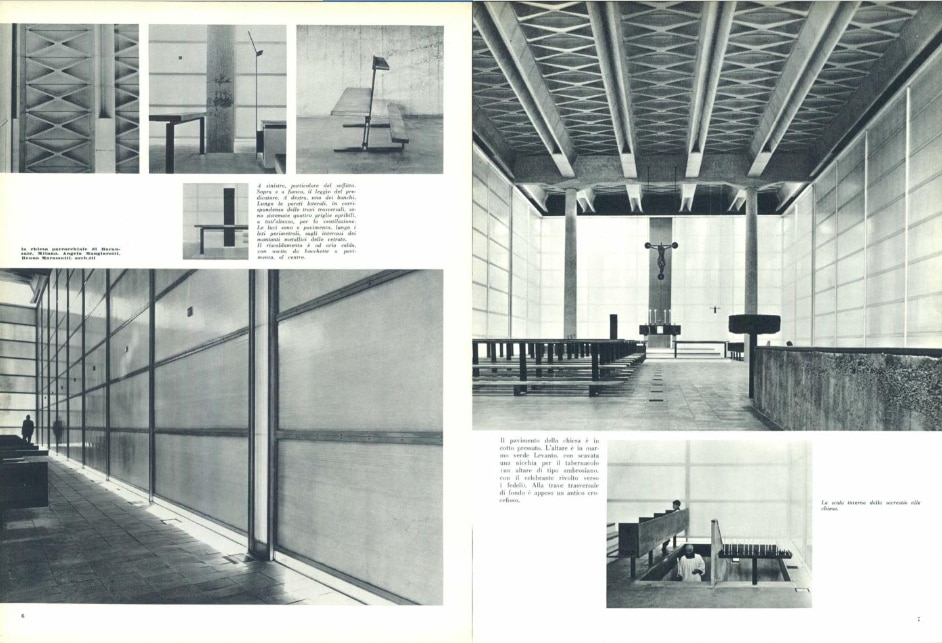

The load-bearing structure of the church consists of four truncated pyramidal concrete pillars, lightly rough-textured, which, with the transverse beams, are the only cast-in-place parts. In fact, the roof consists of prefabricated X-shaped elements, in which high-strength steel cables have been run for prestressing: rectangular ribbed slabs, also prefabricated in concrete, rest on these elements. The perimeter walls are double-glazed in metal frames, with insulating material in between, and are supported on the floor and attached to the load-bearing concrete structure at only four points at the main transverse beams.

At the top and bottom, at the boundary with the roof and floor, these walls are, framed by a thin, fully transparent section, making clear their function as purely non load-bearing enclosures.