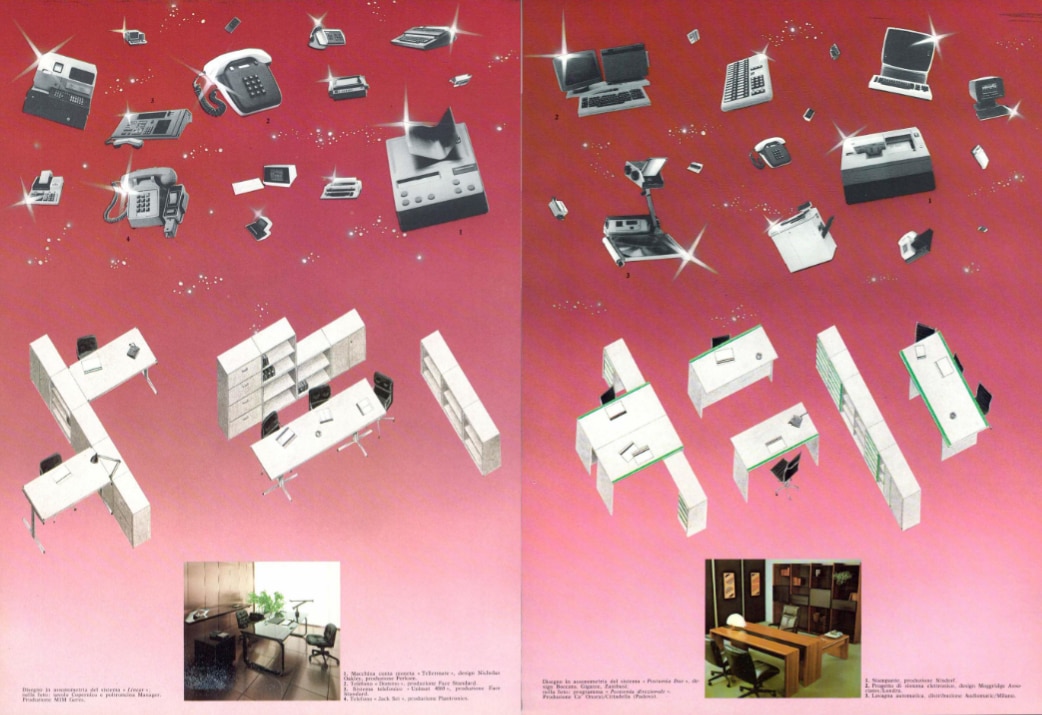

Just as the turn of the millennium had been surrounded by a thick cloud of prefigurations and reflections – a 2001 MoMA exhibition had set out to take stock of the work of the future – going back further, the then inescapable expansion of information technology within the office workflow had also constituted a milestone by the early 1980s, conditioning aesthetics but also substantive trends in the design of process, objects and interiors. In September 1982, introducing on Domus 631 a review of furnishings for the office of the future, mounted on the background of literally stellar graphics, Michele de Lucchi – who would become Domus Guest Editor in 2018 – started from the computerization outline the evolution of desks, from mechanical to electronic, extending towards a prefigurative narration of spaces characterized by ever-increasing efficiency, with different outcomes for the “hardware” of furnishings and the “software” of human practices, with a point still open today, summarized in the passage: “interpersonal contacts will be reduced in strictly operative phases of work (because more time will be spent in dialogue with the machine) but at the same time there will be an increase in the time available for satisfying more ‘human’ social needs”.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

The electronic desk era

The same thing happened about a century ago: the technological revolution had let loose imaginations, and intellectuals, writers, artists and scientists indulged themselves in futuristic predictions. The spark that set it all off was the idea that machines could substitute for man entirely in his physical and muscular functions, thereby multiplying his capacity for action, in particular his power. Machines, huge and minute, kind or aggressive, were invading the world and (for the pessimists) destroying nature and atrophying man, or (for the optimists) making possible the knowledge of the hidden secrets of the earth and universe, relieving man of the hardest and most wearisome work, paving the way for a fantastic civilization of wellbeing.

Now the moment repeats itself, and this time the starting point is perhaps even more fascinating: computers, electronic brains and magnetic memories might replace man in all his rational and mental activities. Today’s predictions concern what has been called the electronic or computer revolution: underway for some years now, but now becoming a mass phenomenon with the spread of personal computers and with an awakening to the potential of computer science.

The advance of the computer revolution today can be seen in the improvement rate of about 30% a year in the ratio of performance: cost and capacity, cost of solid-state primary memories and electronic processing components. This improvement will probably continue throughout the ‘80s and part of the ‘90s, levelling out towards the year 2000 when we shall have instruments that, it is calculated, could be 256 times better than the ones we have today. The fields of our society and economy where this evolution will bear greatest fruit are basically in the automatization of services, in the automatization of industry and finally, with a much quicker rhythm of development, in the automatization of the office.

Of the three spheres of action, it is the world of the office which is best prepared to welcome new technologies, especially because it has used equipment at a low stage of development in comparison with the massive capitalization of the sector. In the space of a few years offices have become an important pace-setting sector thanks to substantial supply and strong demand for new technologies. The phenomenon of “office automation” is quite rightly a question of great moment today. To adopt computer terminology, the effects of the phenomenon can be analysed in the “hardware” and “software” structures of work.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

The “software” structures are those directly involved in work organization itself: this has been in slow and continual evolution for many years now. The stimulus behind development is the search for greater productivity through changes in operative structures. The computer accelerates this evolution and gives greater effectiveness to the results if only because it works in terms of increasingly restricted specialization, and this corresponds to what is happening in the organization of office responsibilities anyway. The computer modifies all the office structures connected with the power of information, which for years formed the basis for the hierarchical distribution of responsibility, and encouraged the specialization of duties by individual group members.

È proprio compito dell’arredo far sì che questa diminuzione di spazio non corrisponda anche ad una diminuzione di confort, ma anzi sia l’occasione per ristudiare la funzionalità del posto di lavoro.

A more functional distribution of information with computers encourages a more efficient exchange among the various groups operating on the same project or committed to the pursuit of a common objective; this will lead to fewer mistakes and avoid all those variations that can occur with the non-direct exchange of information. The basic effect will be that one will work less but more intensively and productively; interpersonal contacts will be reduced in strictly operative phases of work (because more time will be spent in dialogue with the machine) but at the same time there will be an increase in the time available for satisfying more “human” social needs.

As far as “hardware” structures are concerned, the arrival of office automation will cause important changes especially in furnishing, which will become the element designed to absorb the incompatibilities of man and machine. The emphasis on the man/machine relationship is being toned down anyway and we are getting a clearer picture of the real function of ergonomics, the science employed to ensure the healthy nature of man’s relationship with work instruments. It is and will remain a science of testing and evaluation, a control instrument to guarantee “natural behaviour”: it cannot become, as some have occasionally tried to make it, a creative discipline aimed at discovering and producing the most sophisticated modern comforts.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Norms will become in creasingly important and guarantee the constructional quality (especially in terms of safety) of the individual furnishing elements. Standardization of measurements will also allow easier integration of elements, without, one hopes, any reduction in the quality of presentation and design. One of the most important problems will be that of cables: when electronic machines arrive so do cables, and in a much greater numbers. This problem shouldn’t be seen as the bee in the bonnet of some interior designer who can’t bear the sight of a trailing wire; electric cables, telephone wires and interconnecting cables should be organized in separate conduits allowing easy access for inspection, but protected against accidents and tampering. Both horizontal and vertical trunking should be provided within the various furnishing elements, and spaces should be provided for storing excess cable and taking up slack.

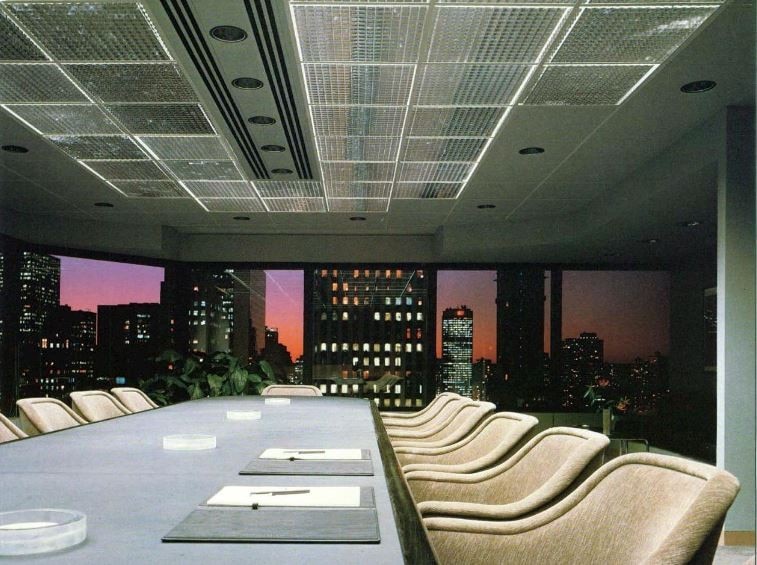

There will be increasing need for furnishing systems of maximum flexibility, not only for the purposes of optimum adaptability to given spaces and functions, but also to allow complete transformation of a space in a few hours or over a weekend. This quality is being increasingly asked of office furniture, which more and more tends to follow the model of American systems (Steelcase, Herman Miller, Westinghouse), the main feature of which is the use of the panel as base element of both structure and image.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

The cost of office space goes up daily and the space available decreases at the same time. Furnishing has to consider the consequences of this: in inevitably it will mean less space per person. It is the specific function of furnishing to ensure that this diminution of space is not accompanied by any di minution of comfort. Indeed, this moment of change should provide the opportunity for restudying the functionality of the work station. Important contributions here come from the American systems with their “vertical work stations”: a high concentration of furnishing elements ensure the “intimacy” of the worker at his work point.

Dedicating less time to work will give people more time at their own disposal and hence will presumably increase the cultural and intellectual expectations of office workers. This will produce the need to successfully individualize oneself in the workplace: hence the need to personalize one’s own work station. We are perhaps the first men of the electronic age and the whole world around us is changing, the office included.

The office is leaving behind its image of workplace of the technological age and is creating itself in a new image. Playing their part in this evolution we find many factors: electronic, technological, social, economic and cultural. Last but not least, there is the image factor: and the image, once perceived, allows us to carry through all the rest, often by more simple intuitive moves that allow us to make progress much more quickly.