When we spoke on the phone at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, Martine Bedin was thankful to have settled in her home in the mountainous region of northern Corsica, where she spends half of her time. The house provides her with all the artistic necessities that allow her to keep working, she explains, namely her professional archives, sketchbooks, and a fully-equipped studio. “As I get older, my work has started to change from simply observing the natural environment over time. I went back to what made me want to go to school in the first place – drawing based on nature.”

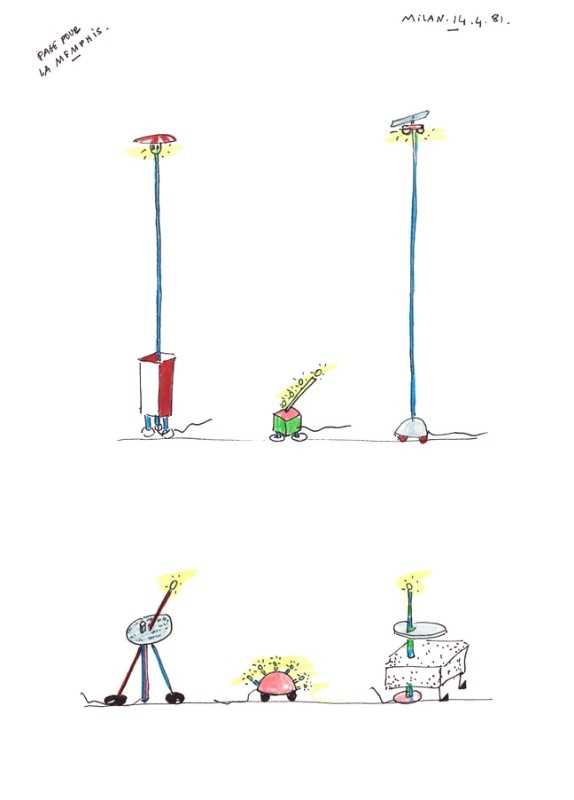

Which would come as a surprise to someone only familiar with Bedin’s early oeuvre, marked by her contribution to the radical Memphis movement in the early 1980s in Italy. With Memphis, she mostly designed experimental lamps and furniture, a journey that she started early on – even perhaps too early. She was only 23 years old when Sottsass took her under his wing upon seeing her Casa Decorata which from the Triennale Milano in 1979. Co-founding Memphis provided her with an ideal design education, a premature experience that led her to conceive an impressive variety of objects with some of the most free and irreverent thinkers in the industry.

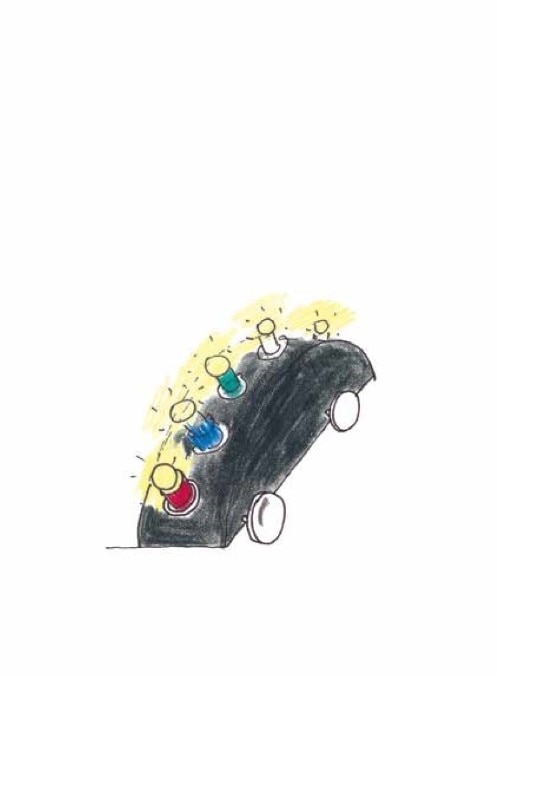

It is in this highly creative context that her iconic Super Lamp came about (designed 1981), the group’s most profitable object, whose prototype is now held in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Designed like a dog, the illuminated crescent-shaped body on four wheels can be trailed around using a long chord. “I wanted to be able to drag the lamp behind me, and that is why I designed the Super Lamp. I am very much a tinkerer, and there I felt like tinkering.”

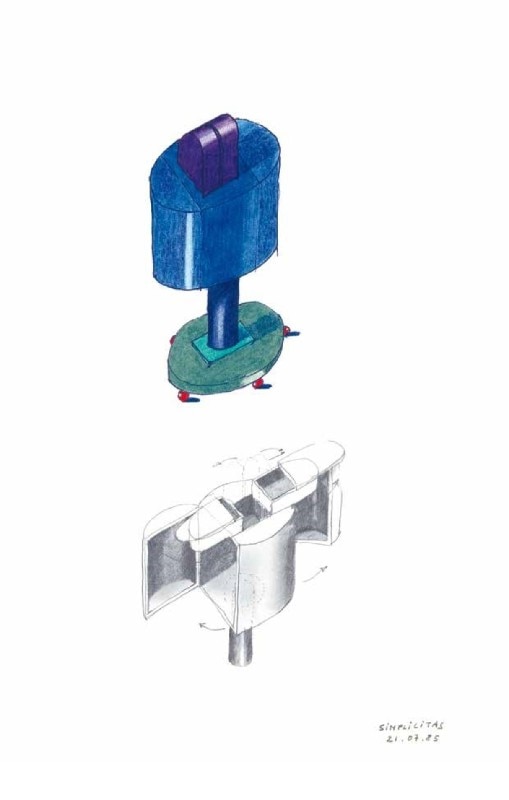

Following her success with Memphis, Bedin devoted further time and effort to industrial design projects involving such objects as small lamps and bathroom taps, for which she gained significant critical and commercial acclaim. “I was interested in industrial design, but quickly turned my back on it, simply because I did not want to be formatted by the industry”. The idea that thousands of her bathroom tap designs would end up in anonymous people’s homes was a frightening one that rang false to her personal artistic calling.

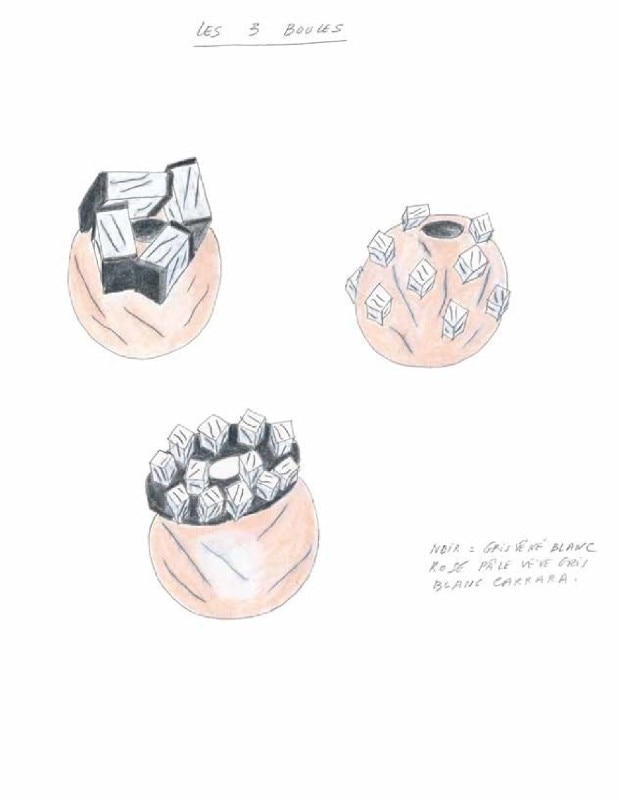

In more recent years, she started to create objects that are unique, “harder to make”, and whose fabrication she could control from their very first conception to their distribution. They remain pieces of smaller scale that are mostly functional. The Città series (2007) comprises unique marble vases inspired by the architectural ruins of eternal cities like Rome, Mandya or Aït Baha, whose carefully-erected forms mirror the precious stones of a deconstructed wall; the Portun’Candela series (2011) includes unique candelabras characterized by their elegant superimposition of silver rectangles of various shapes.

Essential to the conception of these pieces is the process of drawing, which has become increasingly important for Bedin as it catalyzes her individual act of creation. It is Sottsass who said that she took the risk to give drawings higher meaning. “I have realized that the act of drawing can express and communicate the most deeply moving things,” she explains. “I am interested in the mind, in ways in which one conceptualizes the world (through either architecture or design), before an object comes to life. Therefore, I am deeply committed to maintaining the secrecy of intellectual conception, and to the idea that, once the pencil hits the page, that line expresses a concept that has already blossomed in the mind.”

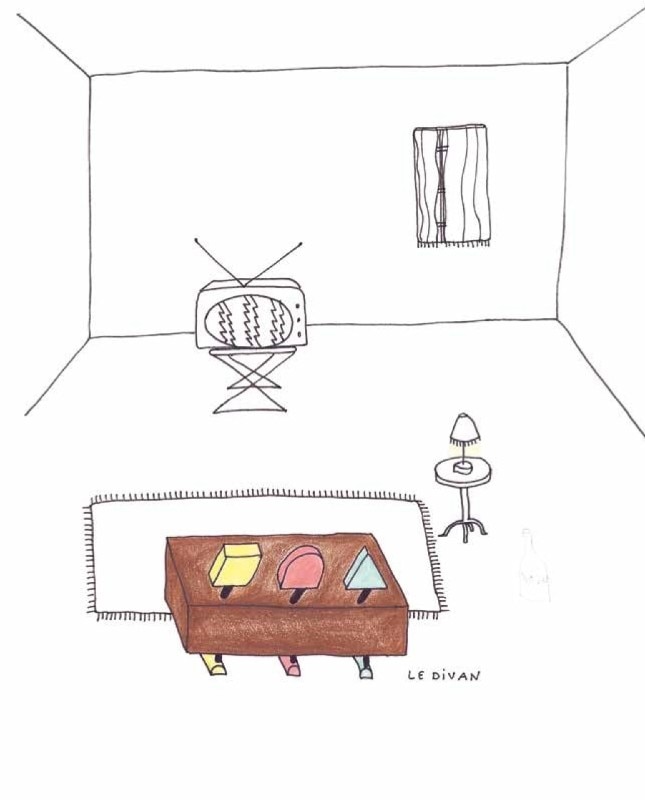

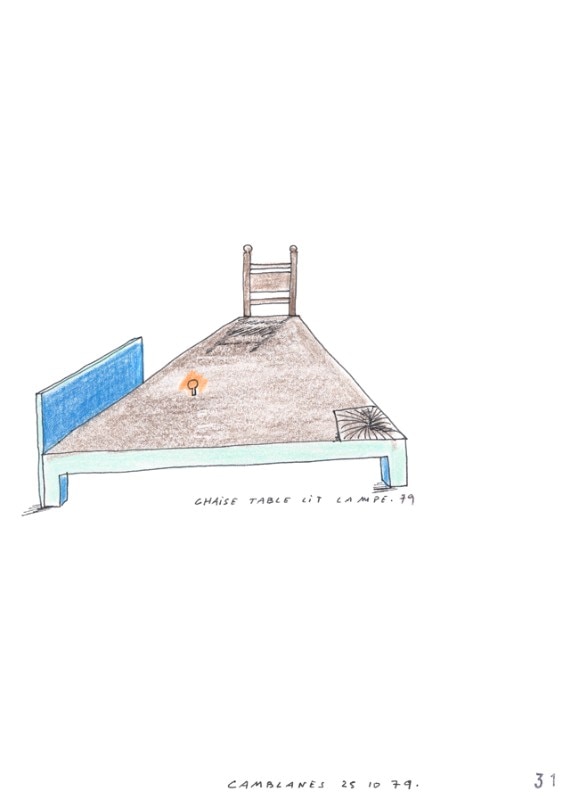

One becomes fully aware of the creative importance of the act of drawing when going through her most recent book, L’objet n’est plus là (2014)—a compilation of select sketchbook drawings from the late 1970s through the present day. Drawings of innovative, eccentric objects for the home, whose usage and materials blur the lines between art and function, fill the pages of this colorful book. She brought some of those drawings to life in 2014 by producing 12 unrealized objects from the sketchbooks, presented in a travelling exhibition at the Speerstra Foundation in Switzerland and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Bordeaux.

One of such pieces, the Table à Tout Faire (or Table for Everything), designed in 1979 and produced in 2014, provides a fitting example of Bedin’s conceptual approach to furniture-making—the idea that one piece alone could embody all furniture in a home. The piece, realized with Padouk wood and straw, features two backrests connected to a main plank, serving as table, bench, and seat altogether. “It is very amusing that these objects from forty years ago, which are a testament to the history of conceptual and post-conceptual design, have been produced today just the way I wanted.”

By valuing ideas, concepts, and drawing above all, the designer’s work so far has been marked by a constant and relentless exploration of concepts and an openness to embrace new means of expression. Simultaneously architect, designer, professor, and more recently painter, she has consciously and cautiously avoided any labels that might endanger the freedom of her creative process. “I am still digging. Like an explorer lost in the mountains, I always look for a new trail through new mediums of expression.”

From her Corsican family home, Bedin works on new projects that incorporate new techniques. Having recently discovered oil painting through classes at the École du Louvre, she started to copy still life paintings by Chardin and Old Masters. This provides the basis for a new collection of vases in dark wood into which are incorporated actual still lifes of her own making— mirroring the concept of a flower in a vase. “It is the first time in my work that the drawing of an object becomes the object itself,” she describes, adding that the series represents a kind of mise-en-abyme and a reflection of her own practice. “It works perfectly with the confinement because, as my grand-mother would say, I have nothing but time.”

Marble matters– exploring Carrara’s legacy

Sixteen young international architects took part in two intensive training days in Carrara, organized by FUM Academy and YACademy, featuring visits to the marble quarries and a design workshop focused on the use of the material.