This article was originally published in Domus 1103, July-August 2025.

The evolution of clothing and textiles maps the arc of our progress as humans.

From the skins of hunted animals to labgrown spider silk and materials engineered at the atomic level. It’s important to see where we have come from to help map out where we may go.

Fur and hide: 100,000 BCE to 3000 BCE

A hundred thousand years ago, we braved ice, wind and rain with animal furs and grasses. We softened the hides of animals by hand and tied them together using the sinews. In 1991, a naturally mummified Copper Age man was found fully clothed in the Ötztal Alps. He was named Otzi the Iceman. His shoes were made of bearskin and stuffed with hay for insulation. He wore a brown bear fur hat with a leather chin strap. And he had a woven grass cape.

Silk and cotton: 3000 BCE to the Industrial revolution

Fast forward 90,000 years, and as societies started evolving, so did our materials. The earliest evidence of silk production dates back to the Neolithic period in China, around 3630 BCE. The Silk Road connected East and West in the first truly global textile trade. Around the same time, another transformational fibre was being cultivated in India and Egypt. As early as 3000 BCE, cotton was being spun and dyed with natural pigments made from plants, insects and minerals. The Indian subcontinent became a powerhouse of dyed cotton.

In the eighteenth century, in England, the Industrial Revolution introduced the mechanical loom into textile production: cotton and woolen fabrics could be mass-produced, using water and steam looms. More than an art, dyeing became a science. After the accidental discovery of mauvein in 1856 by William Perkin, synthetic dyes replaced natural ones: this which once required days of boiling and fermenting with beetle bark or shells could, by that time, be replicated in minutes with industrial chemicals.

By the 18th century, Britain’s Industrial Revolution had mechanised textile production. Cotton and wool fabrics could be mass-produced using water- and steam-powered looms. Dyeing became a science, not an art, with synthetic dyes replacing natural ones after the accidental discovery of mauveine in 1856 by William Perkin. What once took days of boiling and fermenting with bark or beetles could now be replicated in minutes with industrial chemicals.

Polyester and nylon: the rise of synthetics

Synthetics were the next major advance for industrial chemistry. In the 1930s, nylon emerged as a silk substitute. Nylon was strong, stretchy and could be produced in virtually infinite quantities. During World War II, it found new purpose in parachutes, ropes and military gear. Then came polyester. Marketed in the 1950s as a “miracle fibre”, polyester was wrinkleresistant, stain-resistant and cheap to make. Entire wardrobes were now composed of plasticbased textiles. The invention of synthetic fibres fundamentally reshaped fashion, making it faster, more affordable and more disposable.

This year, 100 million tons of synthetic fibre will be produced globally. That’s 70 billion square metres of fabric a year. This 100-year-old technology of nylon and polyester, along with the far more ancient cotton, still makes up the vast majority of everything the clothing industry produces. As designers, both my brother and I, who run Vollebak, saw this as the most incredible opportunity to help push forward the future of clothing.

These fabrics are essentially a high-tech upgrade of skins and furs and offer the same functional promise of helping us survive in hostile environments.

The space race and ballistic textiles

The space race created other material demands, fabrics that could withstand cosmic extremes. This is where heatresistant and high-strength polymers that could survive atmospheric re-entry and high-speed impacts were born. Developed in 1965 by DuPont chemist Stephanie Kwolek, Kevlar was the first para-aramid fibre. Five times stronger than steel by weight, it revolutionised body armour, aerospace insulation and tyres. These ballistic fabrics could stop bullets, resist flames and survive chemical exposure, while remaining flexible and lightweight. When we made our first pieces of clothing, we turned to Kevlar for all these incredible properties. These fabrics are essentially a high-tech upgrade to fur and hide. They offer the same functional promise to help you survive in hostile environments.

Synthetic biology

In this last decade, scientists have begun to look for more organic alternatives. And a new field has emerged at the intersection of biotech and fashion: synthetic biology. Companies such as Spiber, which we have collaborated with, started producing “brewed protein” fabrics by genetically modifying yeast or bacteria to produce silk-like proteins. These are harvested, spun and woven into biodegradable textiles.

Demand for sustainable fabrics is growing, with the market for bio-based fibres expected to grow by 30 per cent over the next decade. As these fibres offer a biodegradable alternative to synthetics. We have also experimented with DNA-based dying methods that use encoded biological sequences to produce colours through natural processes, reducing the chemical runoff typical of traditional dyeing. The results of this dying are beautiful, but it will take some time for the colour palette to expand as the technology is still in its early stages.

Graphene

In 2004, two scientists at the University of Manchester, Andre Geim and Kostya Novoselov, peeled a single layer of carbon atoms from graphite using nothing more than Scotch tape. They discovered graphene. It was heralded as a material wonder: 200 times stronger than steel, highly conductive, flexible and nearly transparent.

In textile form, graphene holds radical promise. Early prototypes of grapheneinfused clothing can regulate temperature, conduct electricity and power small devices. Its conductivity will one day lead to clothes that monitor vital signs, act as sensors or connect to wireless networks.

We used graphene and gold in our Thermal Camouflage Jacket that we made in 2022, which explored how to program a jacket so that it could disguise itself in the thermal spectrum. While the production of graphene for textiles is still early, there’s a lot to play for. The graphene textile market is estimated to reach 1.8 billion dollars by 2030, driven by innovations in wearable tech, smart fabrics and electronic textiles. Its ability to conduct electricity at the atomic level creates the possibility for selfheating and energy-harvesting clothing.

Electromagnetic shielding fabrics

As the world becomes increasingly wireless, electromagnetic radiation from smartphones, Wi-Fi and industrial equipment has given rise to a new generation of shielding fabrics. Made from metallic fibres such as silver and copper, these textiles can block electromagnetic fields and radio waves.

In 2011, NASA used a shielding tent to block external electromagnetic radiation during Curiosity rover testing. Electromagnetic shielding for the Mars rover primarily focused on protecting its sensitive electronics from interference during tests on Earth and, potentially, on Mars.

As we move forward, we may find that our bodies, in terms of how we have to think about electromagnetic radiation, are not so different from the Martian rover.

As we move forward, we may well discover that our bodies are not too dissimilar to theMars rover, in how we need to think about electromagnetic radiation. For us as designers, electromagnetic shielding has vast potential within architecture and travel. We believe it will become a huge part of the luxury experience, where there will be a drive to completely disconnect from the digital world.

Atomic layering: the metamaterial frontier

Material development’s new frontier is molecular-level manipulation, re-engineering matter itself. Atomic layering and nanofabrication now allow researchers to construct materials from the atom up, changing structure and behaviour in ways nature never intended.

These “metamaterials” can bend light, redirect sound and promise super-hydrophobicity, next-level weatherproofing and corrosion resistance, and even invisibility. From MIT to Caltech, textile engineers are experimenting with atomiclayered fabrics that change stiffness on demand, harvest energy from motion or modulate temperature in real time.

The development of metamaterials, powered by atomic manipulation, is still in its early stages, but projections suggest that the metamaterials market will exceed 20 billion dollars by 2030, driven largely by innovations in textiles, energy storage and defence.

As we face an era of climate instability, digital immersion and biological integration, we believe the metamaterial frontier may well become the defining medium of the 21st and 22nd centuries.

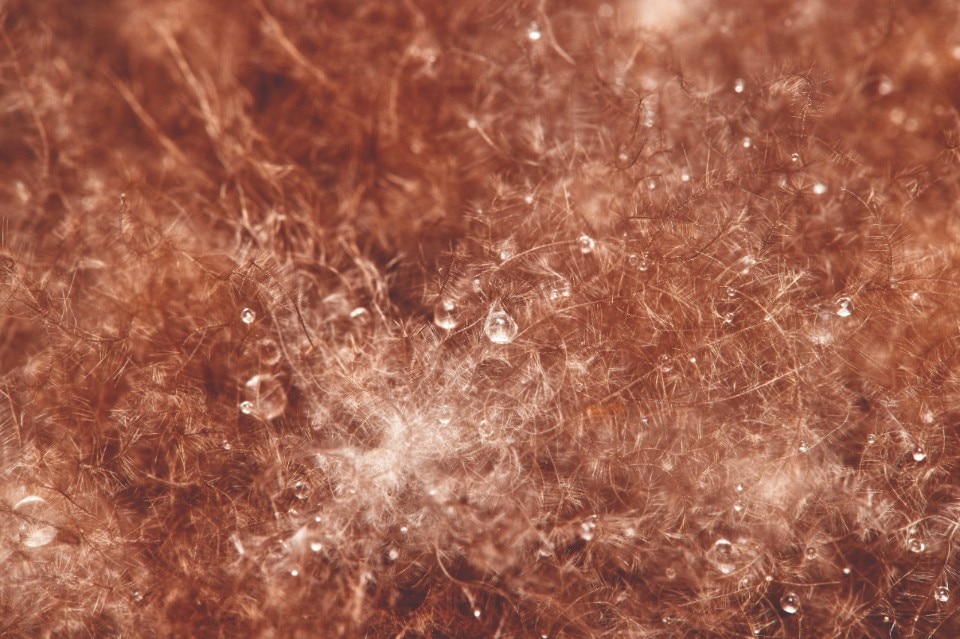

Opening image: Black Squid Jacket, made from polyester fabric and resin embedded with over two billion microscopic glass spheres, mimicking the adaptive camouflage of squid. In low light it is black, and when exposed to brighter light it reflects the entire colour spectrum