From contentment to ecstasy, irritation to rage. Feelings have taken on an urgency and extremism of late. Fuelled by emoji-friendly social media platforms, emotional intensities have been informing everything from election outcomes to the social standing of expertise. Often overlooked in architecture and design exhibitions in favour of (seemingly) more objective interpretations, emotions have been appearing with more regularity here too; implicit in the experiential turn in curation, and explicit in exhibitions such as “Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World”, the new Design Museum’s inaugural show last year. “Emotional States” is therefore a pertinent theme for this year’s London Design Biennale, the second in the series following 2016’s “Utopia”, itself a timely topic in our troubled world.

View gallery

View gallery

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

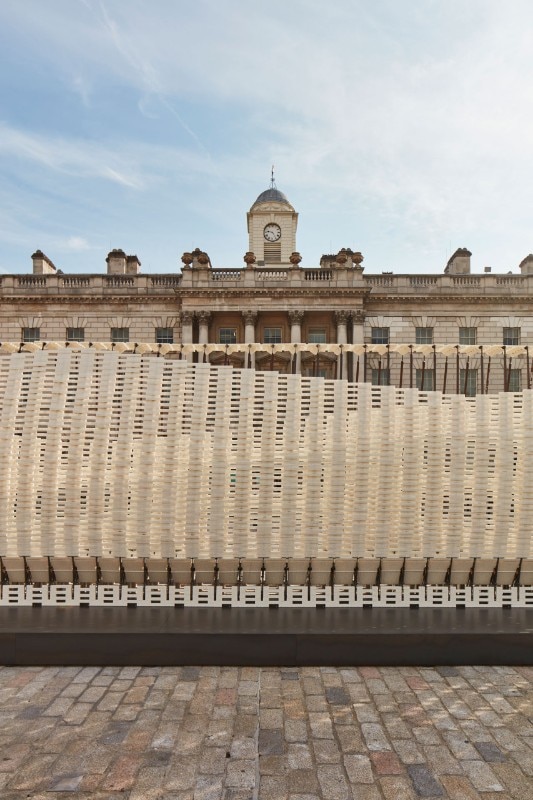

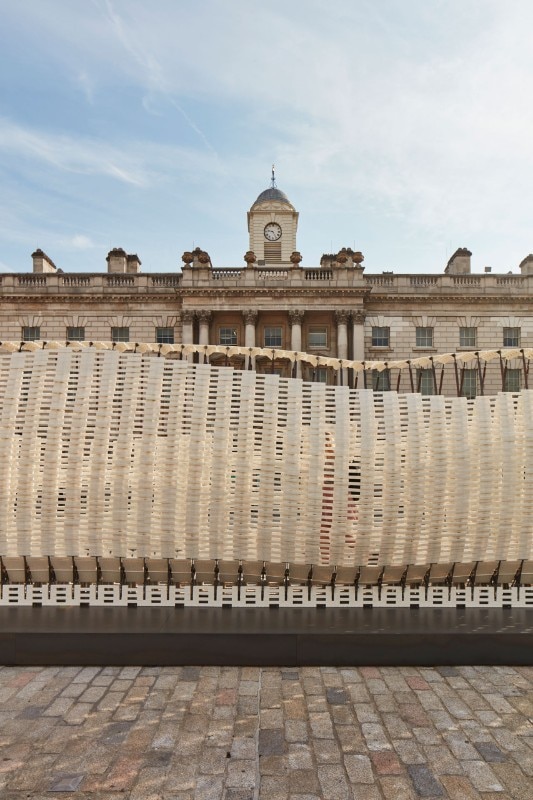

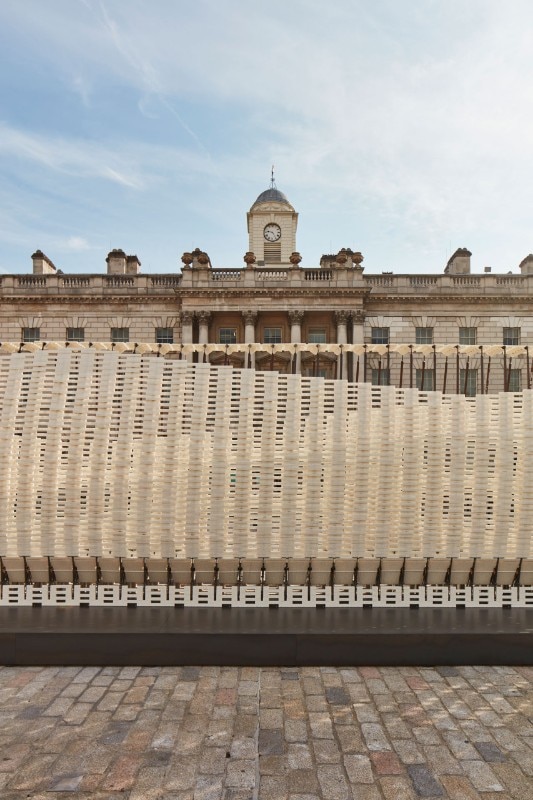

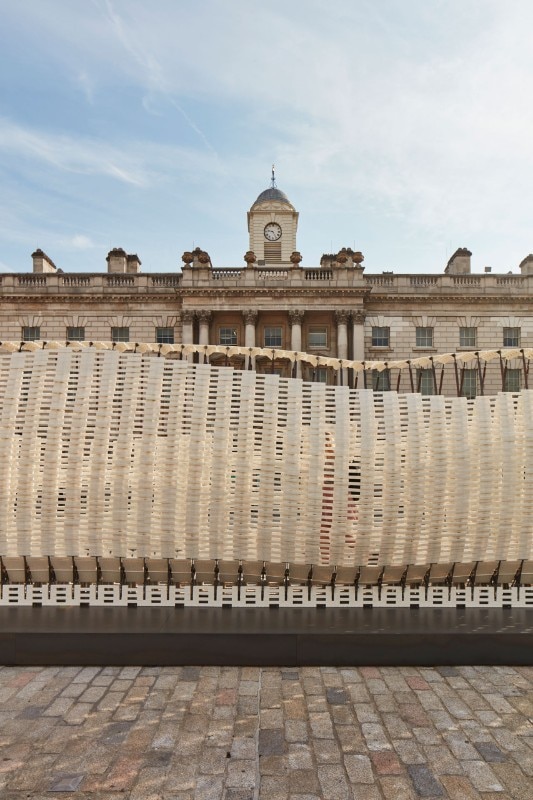

“Emotional States”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Emotional States”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Emotional States”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Emotional States”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

Es Devlin, Panasonic Design, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Palopó”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Palopó”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Palopó”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Palopó”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“State of Indigo”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“State of Indigo”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“State of Indigo”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“State of Indigo”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Body of Us”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Body of Us”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Body of Us”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Body of Us”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Emotional States”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Emotional States”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Emotional States”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Emotional States”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

Es Devlin, Panasonic Design, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Palopó”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Palopó”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Palopó”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Palopó”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“State of Indigo”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“State of Indigo”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“State of Indigo”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“State of Indigo”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Matter to Matter”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Body of Us”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Body of Us”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Body of Us”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries.

“Body of Us”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

Like its predecessor, “Emotional States” posits design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict. This is nothing new in the context of design’s more general socio-political impulse, yet the question of emotion offers an original brief for the participating countries. There are over forty in all, from an impressively diverse geography that includes Egypt, Germany, Israel and Turkey, the USA, Qatar, and Mongolia, as well as a handful of British cities. Their installations are set across Somerset House, a gargantuan 18th century building on the banks of the River Thames. These territorial installations sit alongside a number of special projects commissioned from leading studios and brands including the stage designer Es Devlin and Panasonic Design.

Taking up a prime spot in the central courtyard is Greece’s “ΑΝΥΠΑΚΟΗ” (Disobedience), a 17-metre-long elevated structure designed by Studio INI. Made of recycled plastic, the skeleton-like tunnel shifts and stirs as visitors pass inside, its responsiveness intended as a metaphor for the more adaptive architecture the designers desire. One of the more attention-grabbing works on display, it was not surprising to see a steady queue of visitors awaiting their turn to try it out.

Participation was a key feature in other installations. In “Matter to Matter”, the Latvian entry designed by Arthur Analts of Variant Studio (and which was awarded the Biennale’s Best Design Medal), visitors were invited to leave messages on a green-glazed wall. While in Switzerland’s Body of Us, participation was mandatory. Curated by Rebekka Kiesewetter, the installation consisted of a low platform in the centre of the room, on which a large rectangular petri dish collected bacteria from visitors and the surrounding space. Unafraid to explore more negative emotions in the sense of unease its contents evoked, the installation ultimately sought to provide a positive message, highlighting the bacteria that unite and blur the boundaries between us as humans, an original response to how to overcome our increasingly divisive society.

Several other installations similarly combined spectacle with substance. India’s “State of Indigo” was one of a number of installations that explored craft traditions. In this instance the curator Priya Khanchandani used large scale projections to immerse visitors in the production line of indigo, a pigment interwoven with the nation’s colonial past. Guatemala’s Instagram-friendly Palopó consisted of colourful suspended textiles and geometric forms designed by Zyle and Olivero Bland Studio. As a video tucked in one corner described, the latter has overseen the recent transformation of Pintando Santa Catarina Palopó, an impoverished town on the shores of Lake Atitlán. The designers worked together with the local community to paint its 800 houses in bright colours and patterns inspired by the local textile tradition, with the intention of turning the town into an economy-boosting tourist attraction and instilling a sense of pride.

View gallery

View gallery

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Maps of Defiance”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Maps of Defiance”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Brazilian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Brazilian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Brazilian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Canadian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Canadian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Canadian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Canadian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Pure Gold”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Pure Gold”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Pure Gold”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Pure Gold”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Maps of Defiance”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Maps of Defiance”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Brazilian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Brazilian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Brazilian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Canadian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Canadian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Canadian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

The Canadian participation, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Pure Gold”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Pure Gold”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Pure Gold”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

At the London Design Biennale 2018, 40 countries posit design as a response to our widespread ills, tackling issues from education to the environment, heritage and conflict.

“Pure Gold”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

One of the more sobering installations was the UK’s Maps of Defiance, curated by the V&A in collaboration with Forensic Architecture, the UK-based interdisciplinary studio. Through large-scale video screens and tables covered with documentation, equipment and architectural models, the installation laid bare the destruction being wrought by ISIL to the cultural heritage of the Sinjar area of Iraq, and the studio’s attempts to train researchers to evidence this horrifying act. The emotional charge of the quiet, somber display was testimony to how facts and feelings are not incompatible in an era of post-truth politics.

Some of the installations intentionally sought to elicit an emotional response, but also showed the challenge this presents to often time-pressed or attention-deficient visitors. Both Brazil and Canada’s offerings combined photography and film with evocative environments that sought to engender an emotional understanding of the value of their precious and threatened landscapes, but for me didn’t quite pack sufficient emotional punch. Germany’s entry, Pure Gold, presented recent upcycled design products and furniture from an international set of designers that included El Ultimo Grito, Dirk Van Der Kooij and Piet Van Eek. While the designs were interesting, the argument of the importance of an emotional attachment to objects has been around for some time, and a more critical approach to the effectiveness of this sustainable design approach would have been welcome.

View gallery

View gallery

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

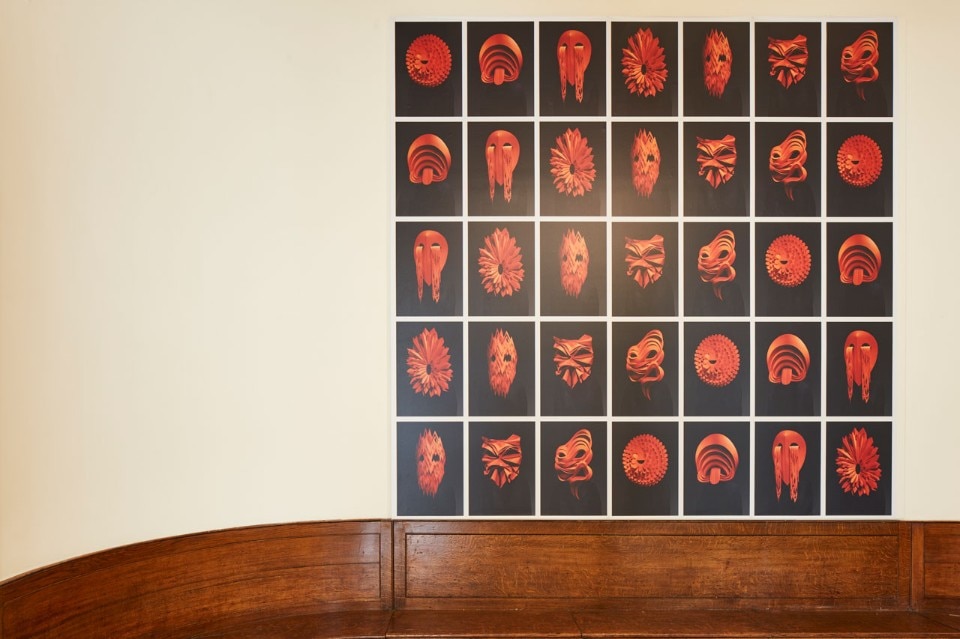

“Face Values”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Face Values”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Face Values”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Face Values”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

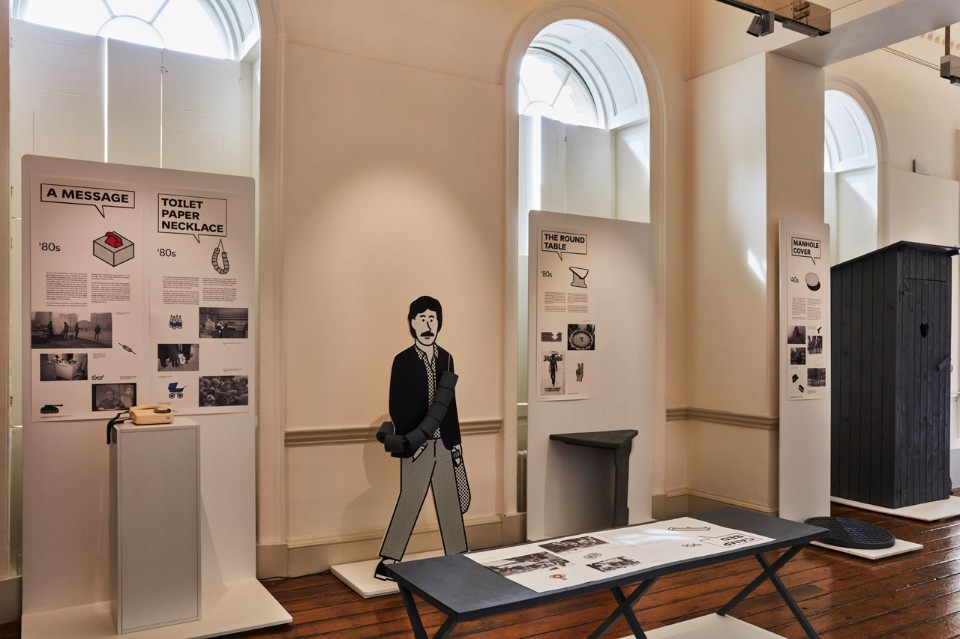

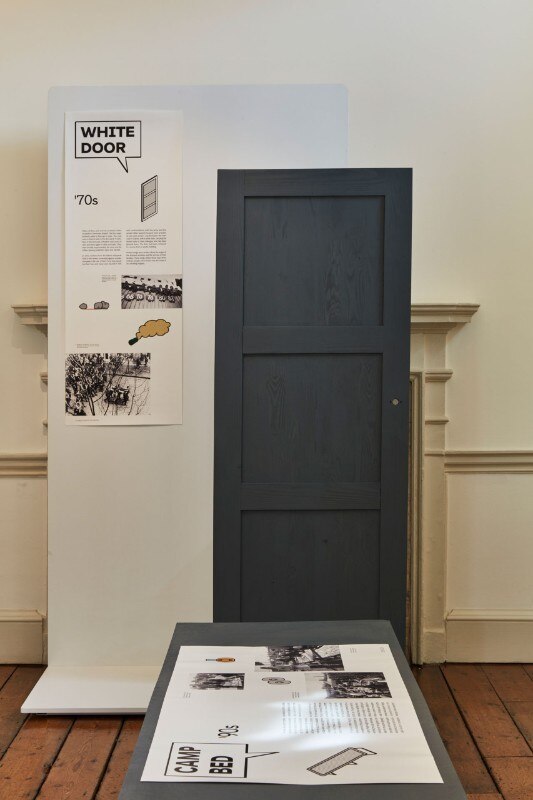

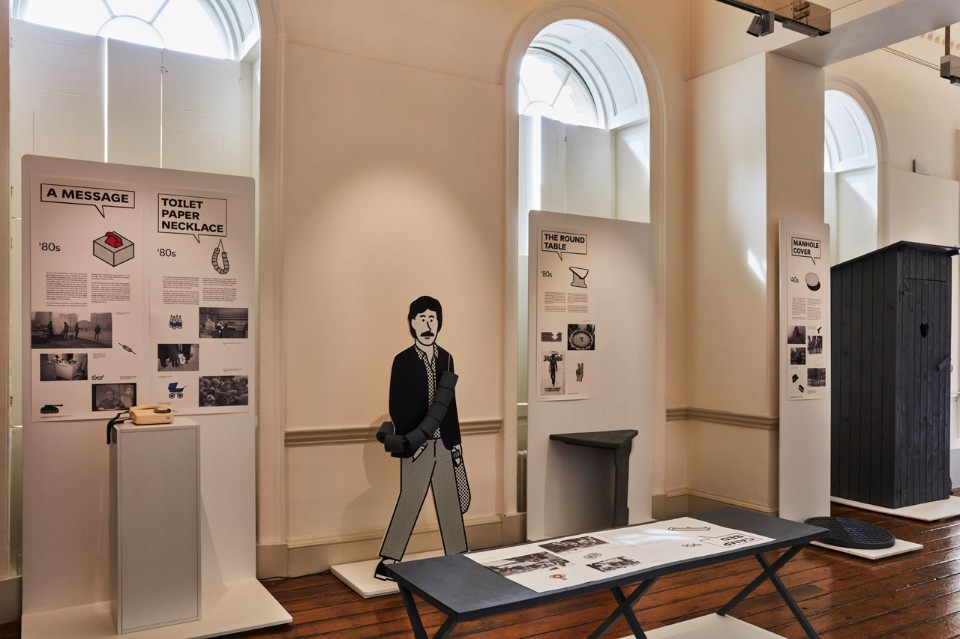

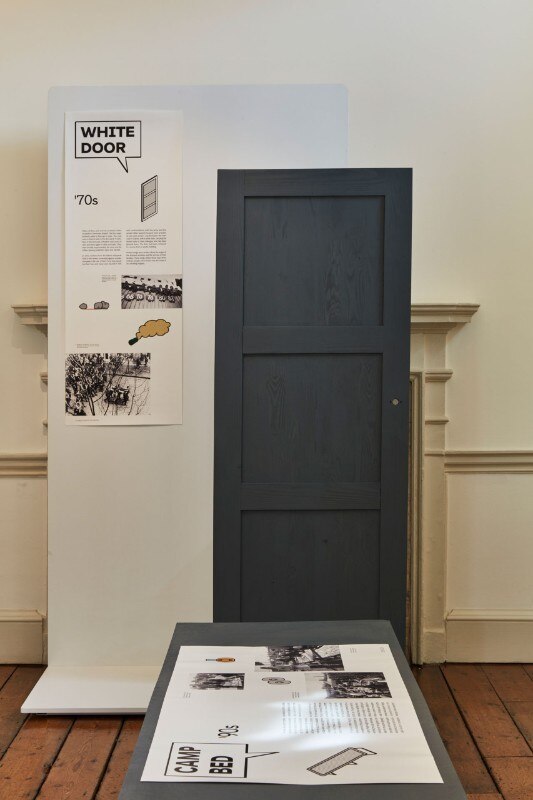

“Matter of Things”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Matter of Things”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Matter of Things”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Matter of Things”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Face Values”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Face Values”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Face Values”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Face Values”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Matter of Things”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Matter of Things”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Matter of Things”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

London. The emotional states of design

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history.

“Matter of Things”, exhibition view, Somerset House, London, United Kingdom, 2018

Two of the strongest entries were deservedly awarded medals by the Biennale. The USA provided one of the most polished and engrossing installations. Presented by the Cooper Hewitt, Face Values effectively mobilized the theme of emotion to expose the increasing pervasiveness of facial recognition technology, and the transformation of every facet of ourselves into data, by inviting visitors to perform a variety of facial expressions for digital displays. At the more low-tech end, Poland’s A Matter of Things displayed ten everyday objects and showed how they are charged with emotional, political and social resonance in Polish history. Curated by Małgorzata Wesołowska, the objects were as diverse as they were humble, ranging from a toilet roll necklace that exemplified the privations of the 1980s to a manhole cover representing the sewers which served as systems for communication and distributing supplies in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. The installation’s simple design fitted the story of how the everyday is often the protagonist in grand historical narratives, and how our material culture is loaded with emotional charge.

As with any group exhibition not all of the installations responded as directly or as strongly to the theme as others, but Emotional States still made for a fresh and insightful exhibition. Collectively the installations also provided a snapshot of a diverse and rich international design culture, and the Biennale is a welcome addition to the design calendar in its global emphasis. Somerset House is also a tricky setting for the biennial. On the one hand it is ideally suited, as its large outdoor areas and corridors of rooms create easily identifiable spaces for individual installations. On the other hand, the building’s scale, sprawling nature and multi-functional use make it difficult for the Biennale to fully exert its presence and it is easy to miss out some areas of the exhibition, despite Pentagram’s arresting signage and visual identity. Overall however, Emotional States is a welcome second edition to the series, and it will be interesting to see how this Biennale develops.

- Event:

- London Design Biennale 2018

- Exhibition title:

- Emotional States

- Opening dates:

- 4–23 September 2018

- Venue:

- Somerset House

- Address:

- Strand, London WC2R 1LA, United Kingdom