What can one say of Jerusalem, a city which has always been contested by differing cultures, a cocktail of traditions, stories, legends, religions and people? This melting pot, which has no equal anywhere else on the planet, a symbol of excellence for that which should be considered as integration (but which is difficult to truly consider as such), could only lead to such a rich Design Week full of projects, situations, adventures and dreams, all with a single common denominator: looking into the future thanks to the magical potion of design, an instrument which is capable of transforming and improving our society. A necessary hope.

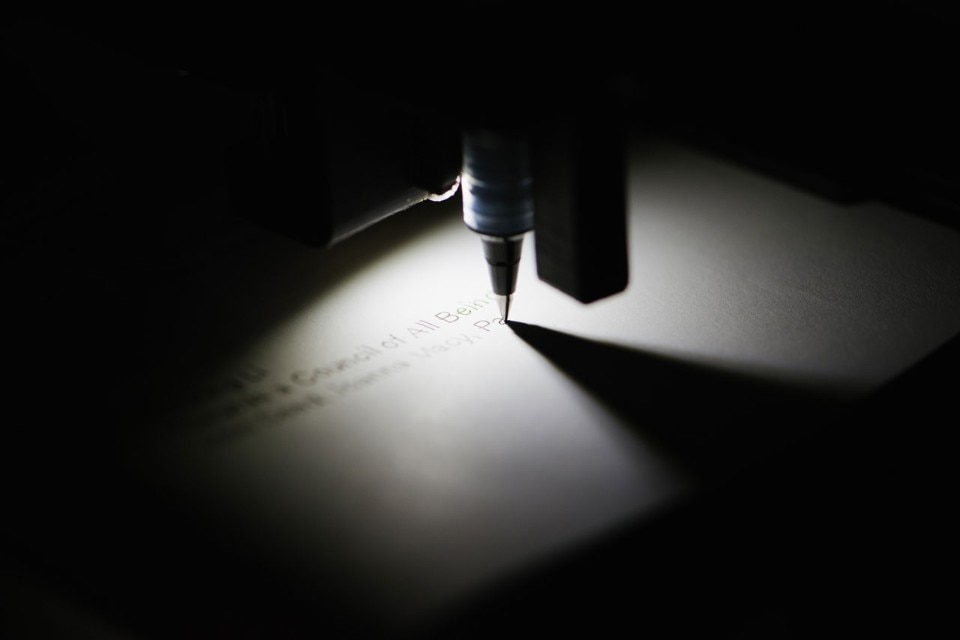

The third edition of the Jerusalem Design Week was a frenzy of information, images, stories and performances which is hard to condense into a description of just a few words. The excellent work carried out by the two curators, Anat Safran and Tal Erez (both with an excellent CV behind them, extraordinary passion and just as much talent) is as appreciated as it is impossible to summarise. Their main exhibition, “The Human Conservation Project” speaks of the efforts of humankind for self-preservation, both on a biological and a cultural level, touching on important themes such as politics, history, and the society in which we live, with a specific focus on the particular geographic context.

View gallery

View gallery

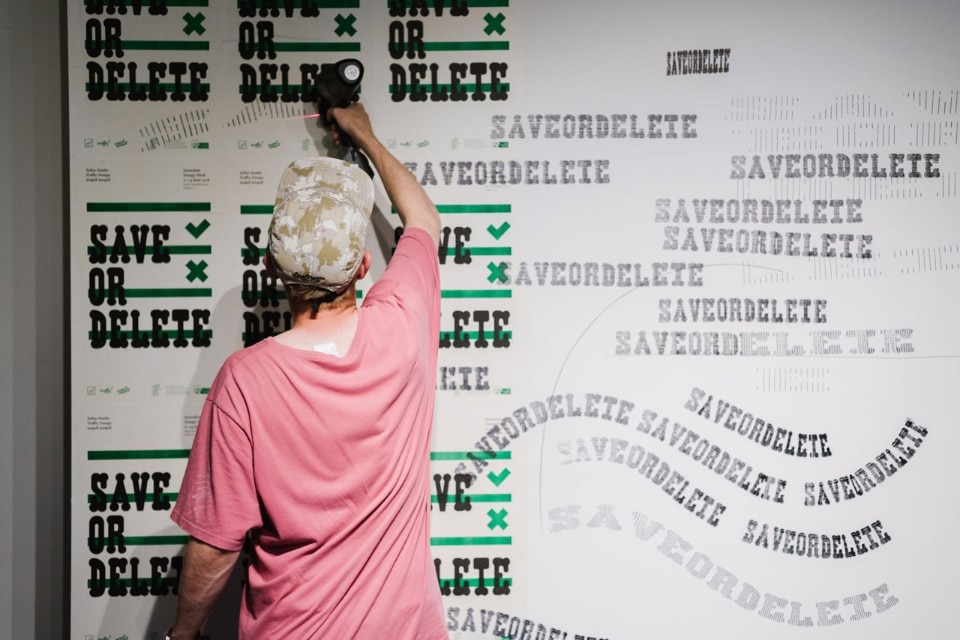

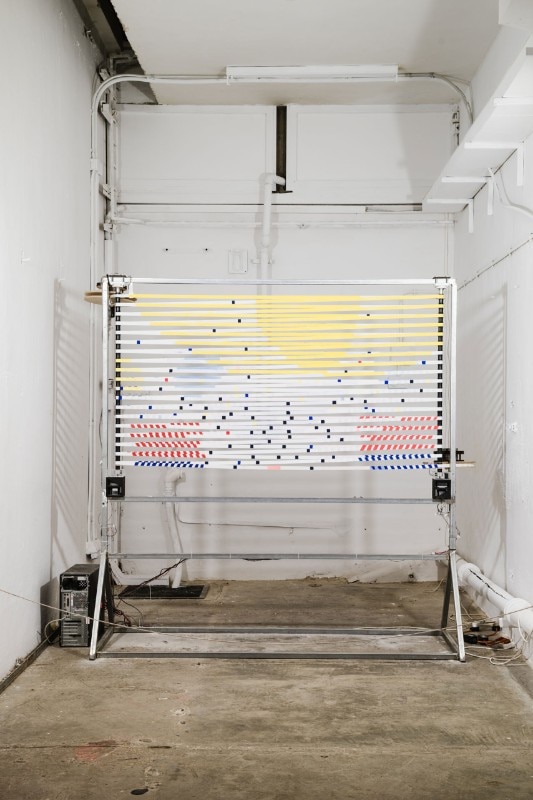

This is the case with the exhibition “Flag” by Shy Ben Ari and Zohar Dvir, a successful investigation on the theme of the flag, an object capable of immediately transmitting a clear unique message thanks to a series of precise and pre-existent codes which bring together cultures, places and situations. The national white and light-blue flag, which incarnates history and dreams, adopted on 28 October 1948 (inspired by ritual shawls - the tallit or talled - with the star of David at its centre, designed for the Zionist movement in 1891), a narrative device with which various authors examine the current situation in the state which was founded seventy years ago. This is an initial example for an examination of the multitude of voices orchestrated by Safran and Erez, which clearly presents the plurality of opinions and visions which here are interpreted by the over 100 local and international designers who were invited to take part, all called on to examine, from different points of view, themes such as our unavoidable cultural baggage, what to keep and what to leave behind from this, in order to understand who we are nowadays, but above all who we will be tomorrow. What to keep, conserving the past to improve our future. Concepts of a notable specific weight, including old age (100 years old by Tali Kushnir and Alexandre Humbert), physical disability (The Alternative Limb Project by Sophie de Oliveira Barata), are expressed thanks to various commissions from the curators.

View gallery

View gallery

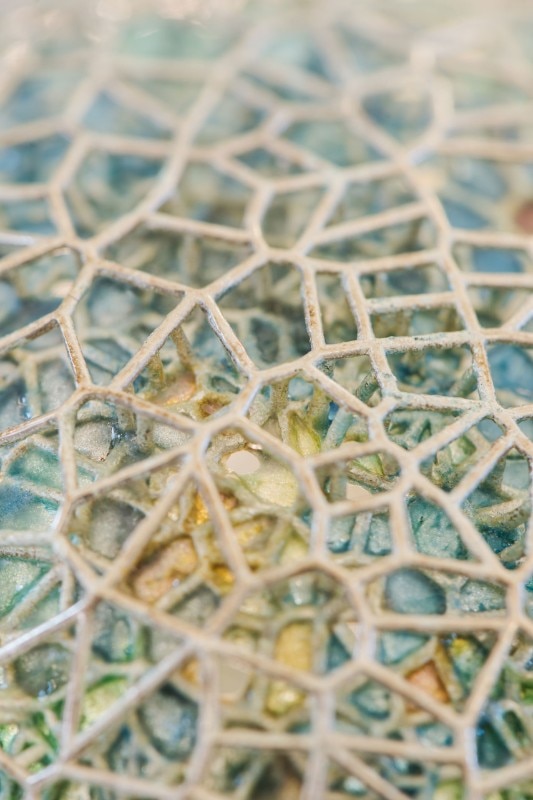

The title or theme of the edition is “Conservation”. Preserve, maintain, and improve our world, and therefore ourselves. Set up by the Ministry of Jerusalem and Heritage and the Jerusalem Development Authority, promoted by Hansen House and managed by Ran Wolf and Chen Gazit from Ran Wolf Urban Planning and Project Management LTD (therefore with public money), this design week managed to bring to the holy land (between 7 and 14 June) sector specialists, the curious and enthusiasts, even with temperatures of 45 degrees in the shade. Distributed throughout various venues beyond the walls of the old city, including the Bezek Building, Alliance House (the location of “Flag”), the Hansen House building reigns supreme. First a leper colony and then a mental institution, this large 19th century complex which is set out over multiple floors and is constructed in traditional Jerusalem stone, is currently the main venue of the event and for the Hansen House Centre for Design, Media and Technology. On crossing the threshold, we are welcomed by “Pro Jerusalem - 100 Years of Preservation”, an exhibition curated by Alexandra Topaz, Hadar Porat and Keren Kinberg, which explains how in this city, as far back as 1918, attempts were made to set out general basic rules for the preservation of its (architectural and archaeological rather than religious) integrity by the Pro-Jerusalem Society (PJS), an association founded by the then-British governor of Jerusalem, Sir Ronald Henry Amherst Storrs. A manifesto with precise regulations set out what could or could not be done, how practicability and aesthetics could be improved and contained, above all, a warning not to destroy or to construct anything on this small patch of land. Nowadays this would be classified as territorial marketing. Legislation was set out regarding everything that should and could take place within the fortified walls, from the porcelain street signs to urban planning. A series of common objects represent the image of a place characterised by a powerful and intriguing energy. A wide range of everyday objects - from glittered souvenir postcards, pieces of local stone, ashtrays, judaica in various forms and origins, and even mosaics celebrating the first 100 years since the institution of the association which created the image of JSL as we see it today.

View gallery

View gallery

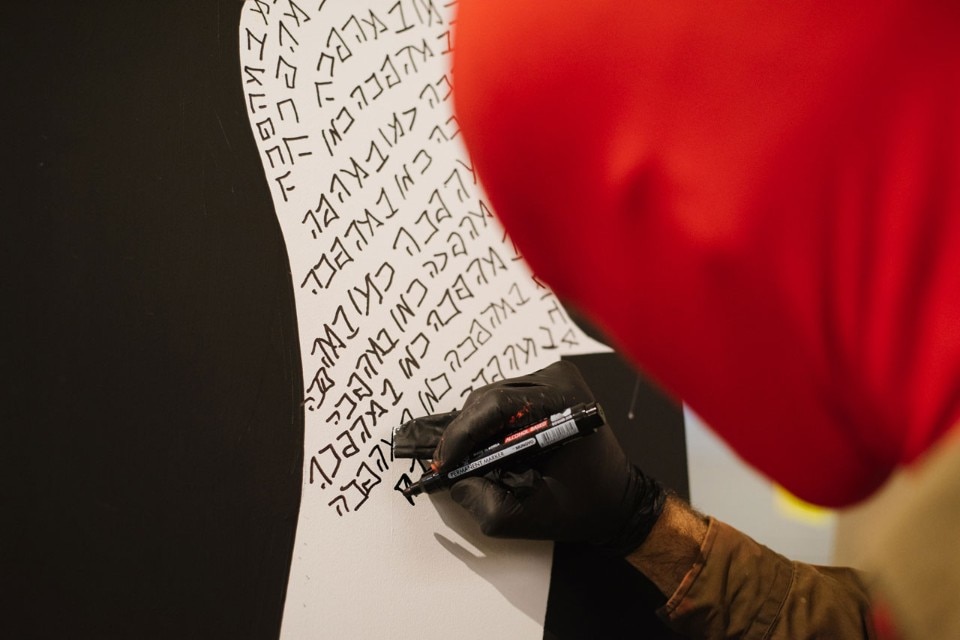

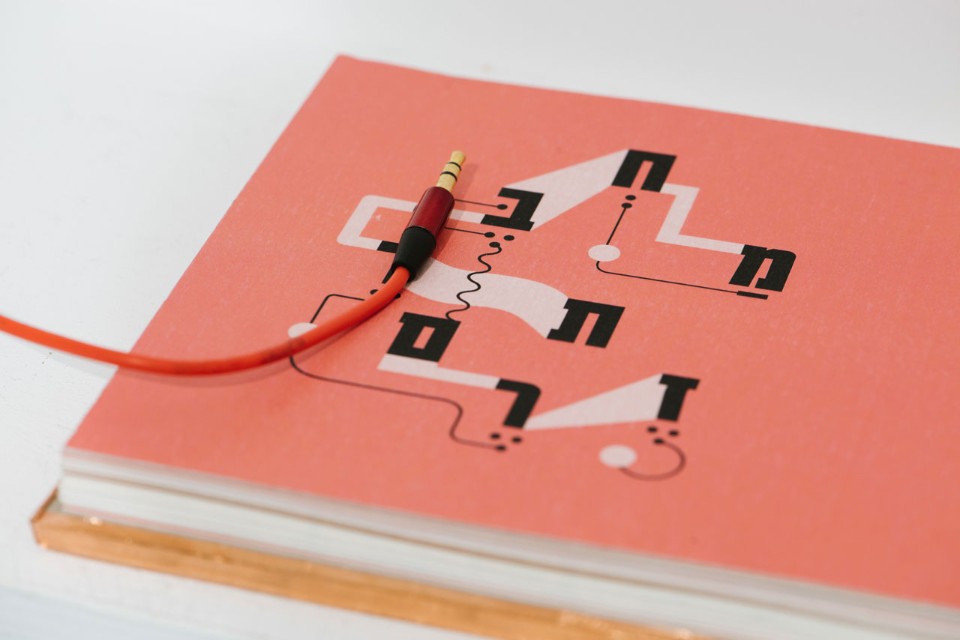

The present looks to the past with the eyes of the future, even if some are certain that tomorrow will be exactly like yesterday. In the ample spaces of the nearby Jerusalem Theatre, the exhibition “Haredi-made: The Product on Orthodox Society” regarding the mysterious and hidden universe of the Haredi (strictly-orthodox Jews) presents a series of interpretations by members of the community (which is in itself an interesting aspect) on customs and traditions, as well as rules (countless) which govern the daily lives of these religious figures; from a series of wig heads which look like statues (almost revolutionary in this rigid and inflexible tradition) to a black trolley used to carry the Torah around while on holiday. The exhibition curated by Noa Lea Cohn, a practising member of the Haredi community as well as heart and soul of the Hamiklat Gallery for Contemporary Haredi Art, tells of a distant world where integration and openness to a certain simpler, but no less fascinating, form of contemporariness. In fact, it is quite the contrary. Continuing in the exploration of the exhibition spaces, we also find a Revolution Square, with quality performances ranging from a frenzied group dance to express haircuts, all under the artistic direction of Tal Gur. In this square full of people and moments, everyone has the opportunity to express themselves freely, without rules.

View gallery

View gallery

As well as collaborations with the two cornerstones of local education, the Shenkar School of Engineering & Design (“Gaon’s Salon” is a series of talk shows curated by Galit Gaon) and the Bezalel Academy (including the unmissable exhibition by the students of Maya Dvash), Anat Safran and Tal Erez have also managed to set up a network of international partnerships with institutions, museums and foundations such as the Istanbul Design Biennial, the Polish Institute, D-Day Paris, and the Italian Milan Design Film Festival.