In the past few years, conversation about design has been increasingly dominated by a certain theme: the generative process. Standardised form, or even pure form itself, seems almost aimless in comparison to a new kind of object that is unique within a consciously imperfect series. For the user, these curious mutations represent a special type of commodity, receptive to the infusion of value and memory. Process, it would seem, is a kind of elixir, curing design fatigue and consumerist shame without sacrificing a whit of aesthetic consciousness.

Thus there is something uncannily marketable about this phenomenon. In theory, the notion of process suggests a broad range of transformations, transactions and assemblies in the course of an object's life. In practice, however, the situation is otherwise. Process-based design tends to delineate a precise timeframe, one that begins when prepared materials are obtained and ends the moment the object emerges from its mould. During this span, the designer is often the sole agent of change; the studio, like a hermetic laboratory, is often the sole context for manufacture. When these defiantly non-homogeneous objects leave the workshop for the "real world", they are primed for direct consumption, "inherent value" already included.

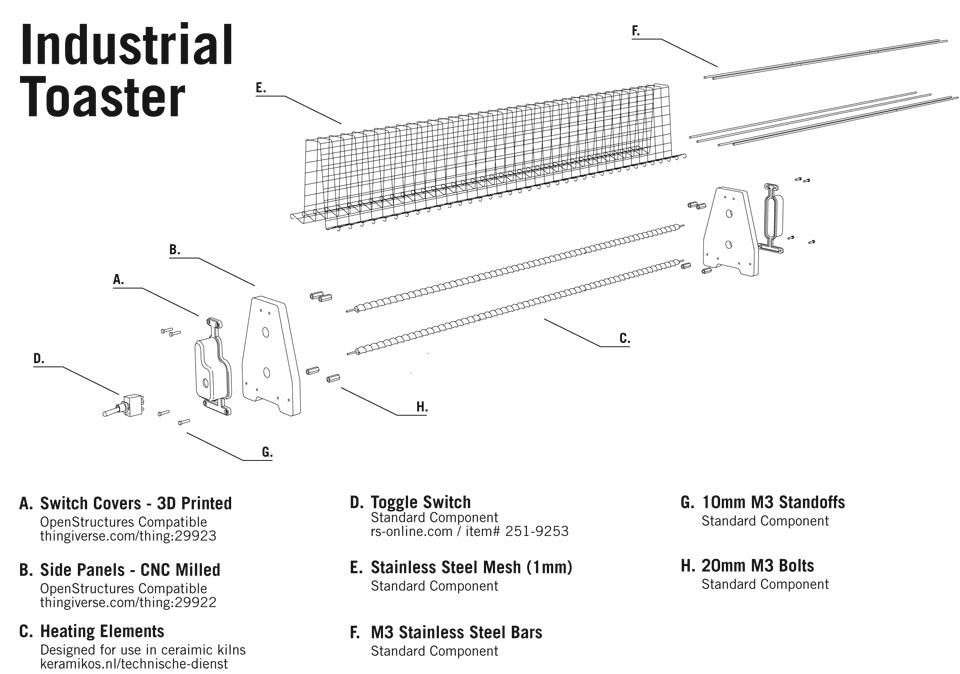

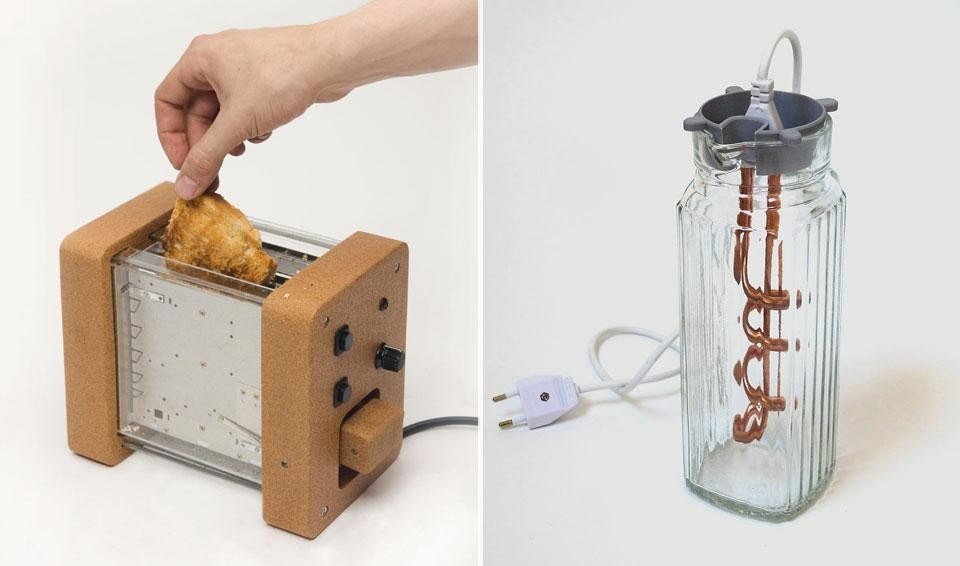

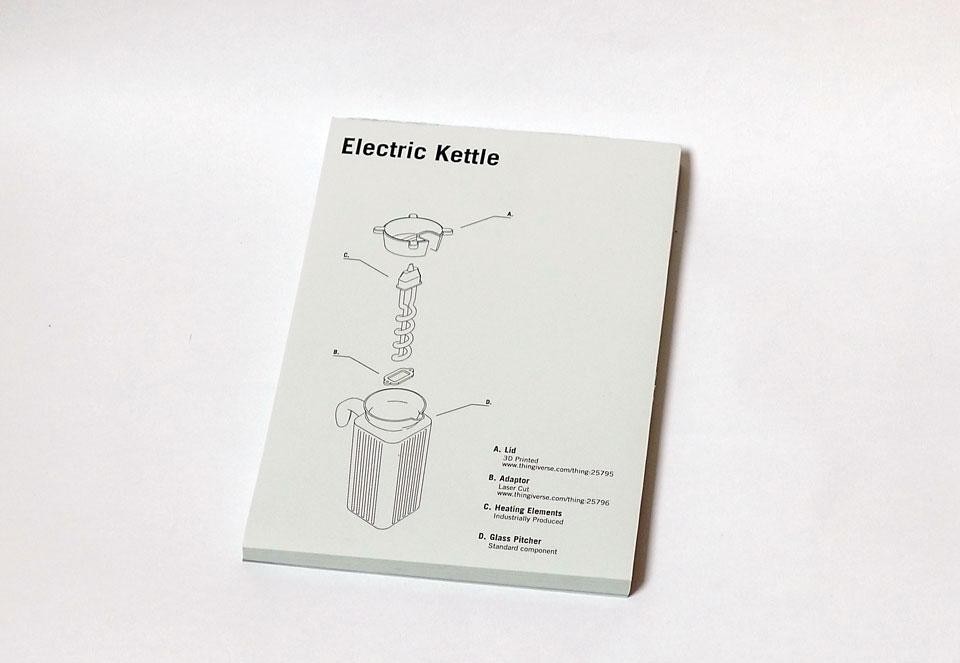

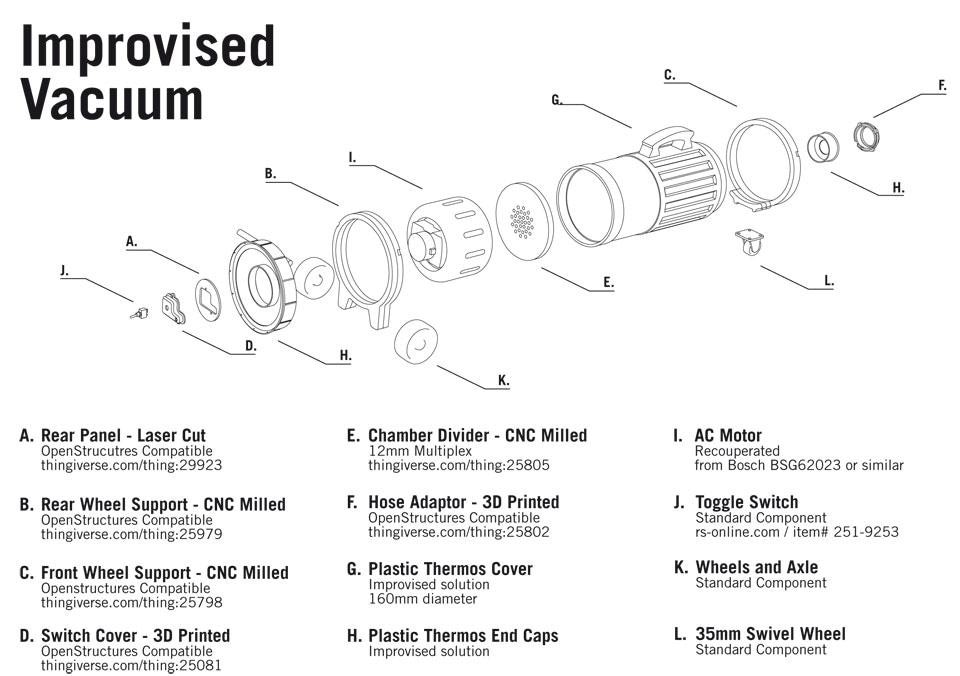

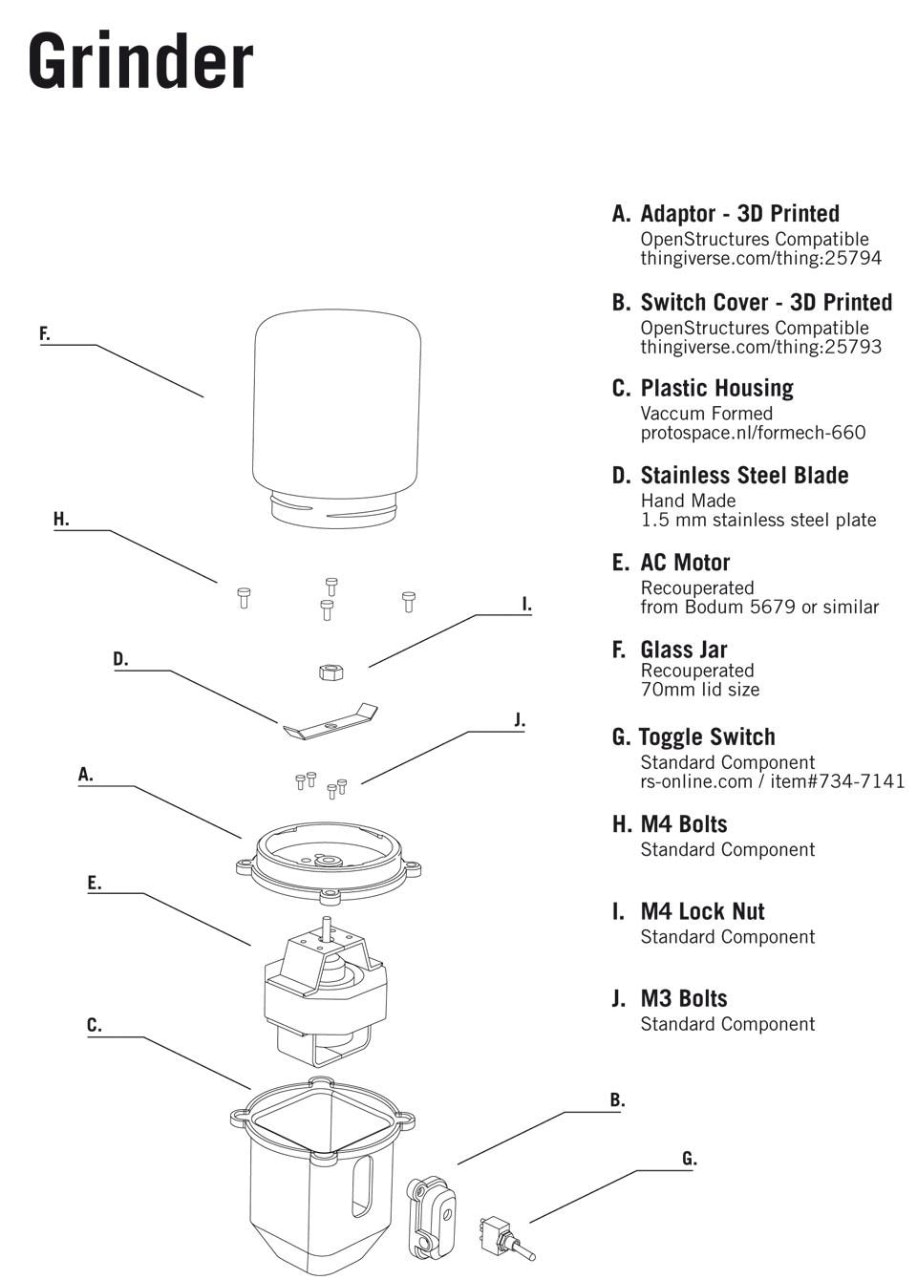

In the seminal Toaster Project, in which he reverse-engineered the ubiquitous kitchen device and reconstructed it from the ground up, London designer Thomas Thwaites discovered, for example, that 30 per cent of the world's total nickel production (more than 1 million tons per year) can be traced to a single mine in Norilsk, Siberia. The heating element in every toaster is made of nickel. If Thwaites was a pioneer in the field, using design as an investigative tool, then recent graduates Jesse Howard (Gerrit Rietveld Academy, 2012) and Gaspard Tiné-Berès (Royal College of Art, 2012) may represent the next phase, in which design becomes a participatory and reparative force.

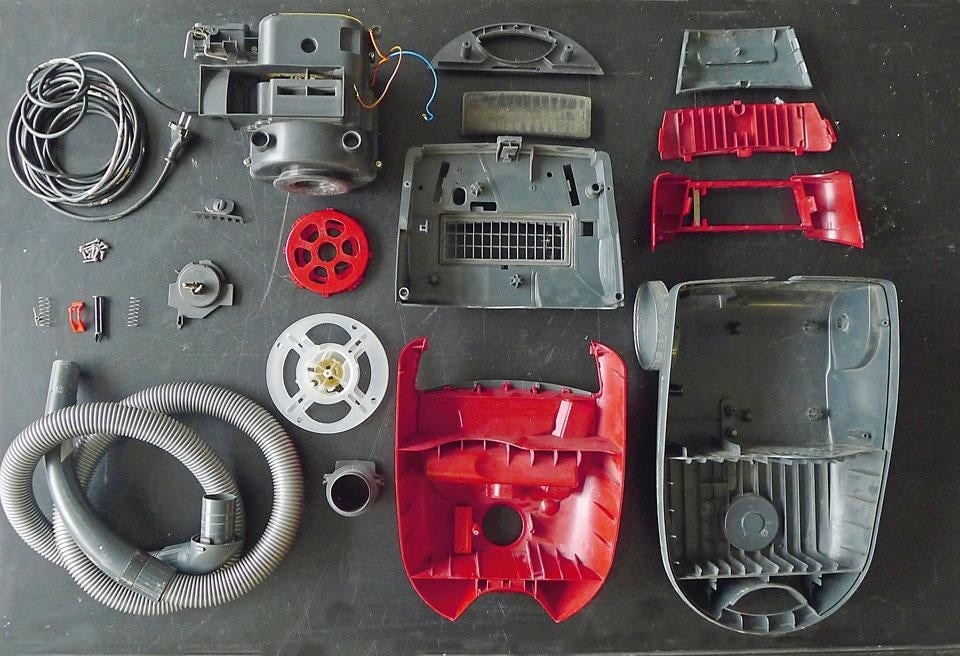

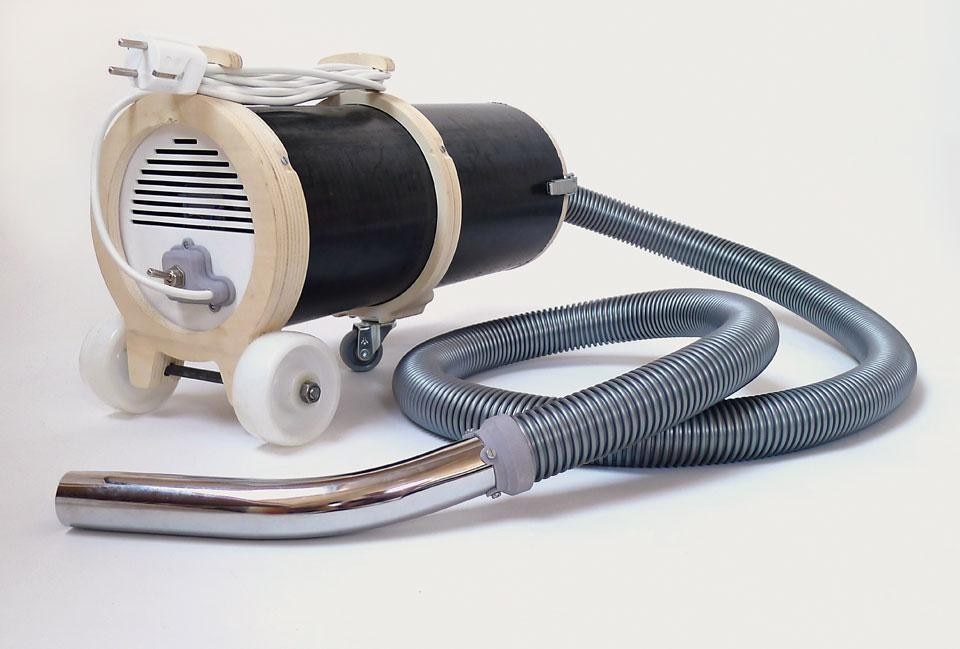

For all the apparent banality of these actions, there are a growing number of designers who embrace them as full-fledged stages in how things take shape. These individuals construct their design intervention as merely one of many inputs into a material, functional outcome alongside the user, the market, the political economy, the environment and society's customs