Amadori had seized the favourable opportunity – resulting from the debate on the concept of post-modernity – to relaunch the connection between antique and contemporary, while searching for a formula that would re-enhance an "intermediate" quality between the two.

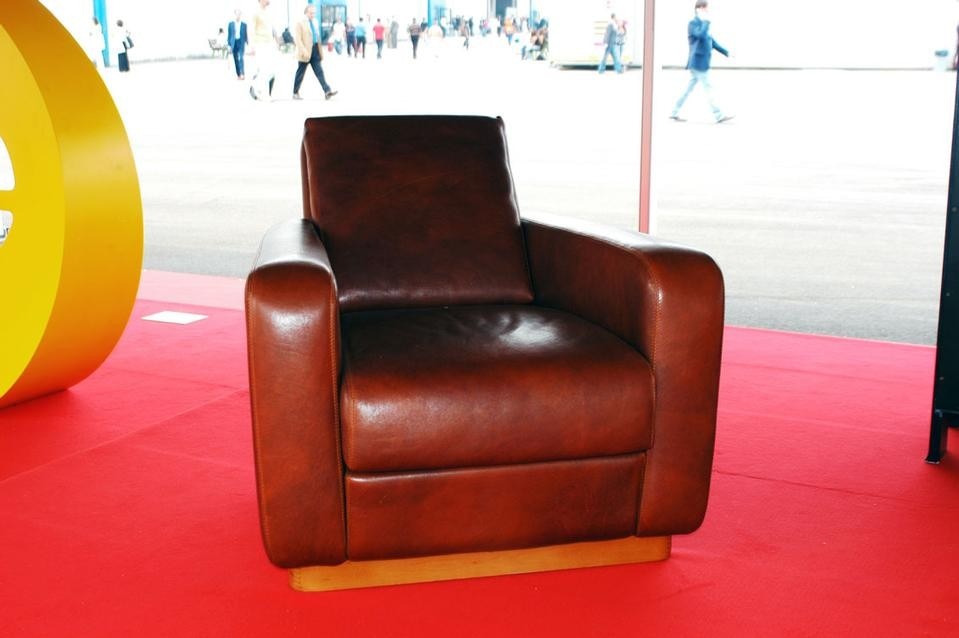

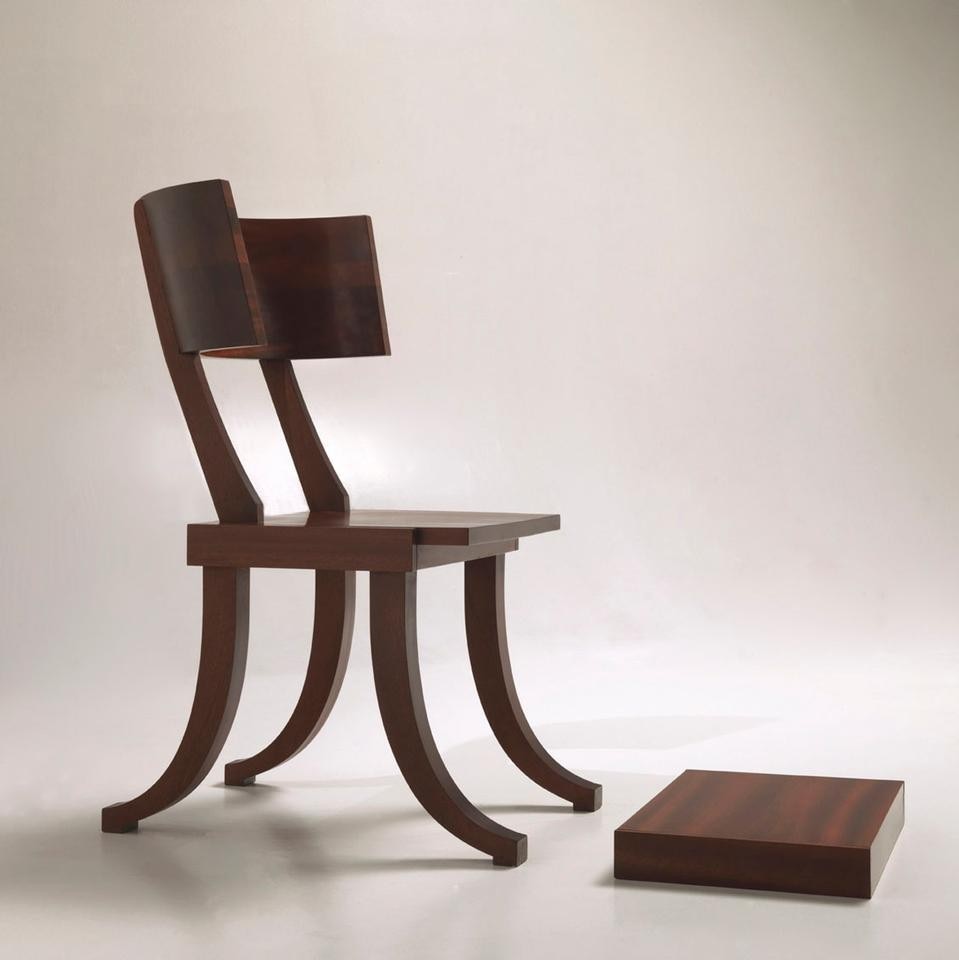

That opening had been influenced by Amadori's friendship with a circle of Roman personalities. These included Francesco Moschini, but especially Paolo Portoghesi, who had displayed Amadori's work as a painter in his Apollodoro Gallery. With their galleries, the two theorists and architects animated a transverse development of which Abitare il Tempo represented a new horizon: that of furniture inspired by great classical paintings. The "Il tempo abitato" exhibition (1986) adopted Carpaccio's Dream of St Ursula painting (1494) as an invitation to designers and craftspeople to express themselves through arredo in stile ("period furniture"). That debut was to have its sequel in the myth of the remake, or as Nicola Pagliara had called it, "The play on words of memory". But these were remakes of a different sort, and to be sold on the market, such as the majestic seating inspired by Jacques-Louis David's painting The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons (1789). The organisers and their advisors viewed the renewal of period furniture as "a positive development free from monotony and whose available criteria left enough room for individual freedom" (Amadori).

That enterprise proved an arduous but feasible task, guided by a cultural determination to steer furniture crafts back into the "high range" by recapturing lost qualities of form rediscovered through art and design.

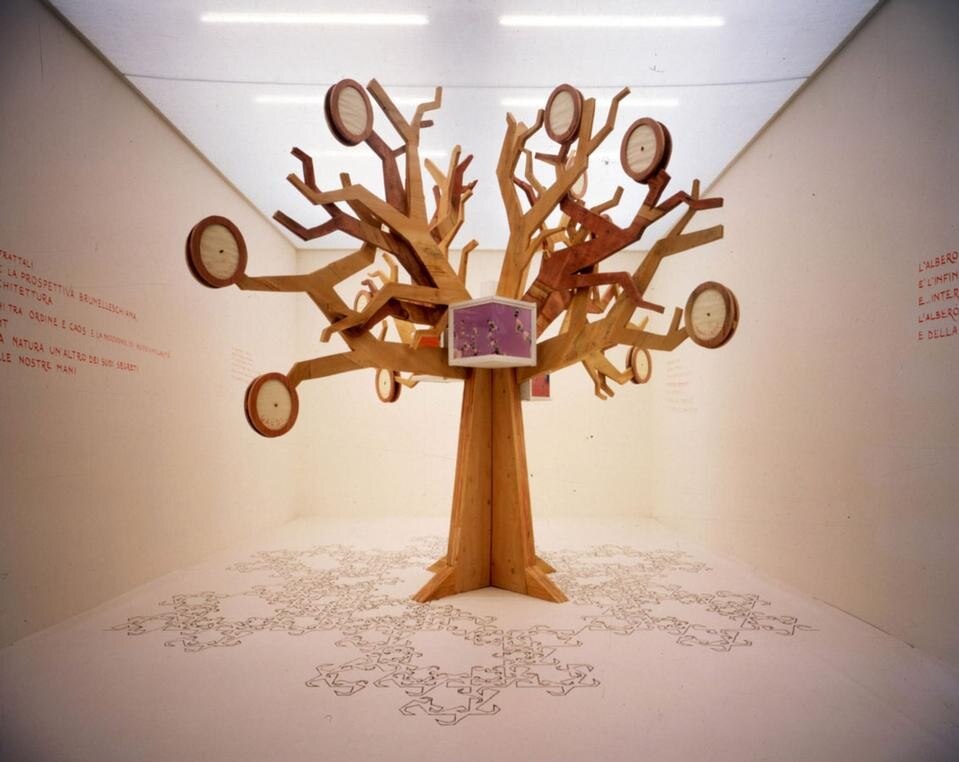

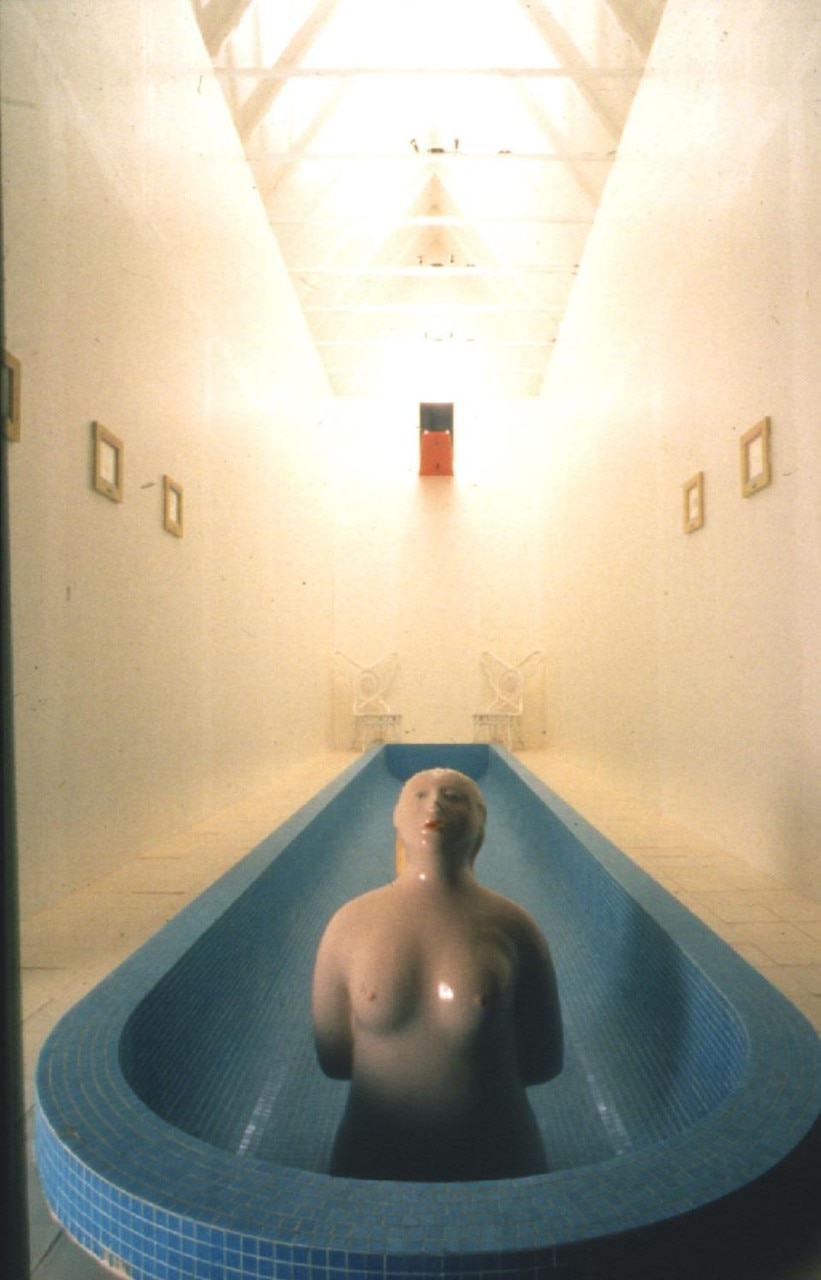

A militant artist-designer from the Milanese radical avant-garde groups of the 1970s, Ugo La Pietra strongly influenced the years to follow. More than any other, La Pietra succeeded in defining concepts that appealed both to entrepreneurs and to craftspeople. Through Abitare il Tempo, La Pietra launched his idea of the "Fatto ad Arte", which he described as a particular relationship between design and art objects that would embrace certain products such as furniture. It was necessary, he added, to remember that people at that time were looking for new patterns of behaviour that would increasingly preserve and re-evoke classical tempos. Hence, asserted La Pietra, the need to situate these between the traditional and the modern.

At the first congress on the subject of "The Concept of Classical" (1986), Ugo La Pietra defined three working models for the new fair. The first was that of the faithful replica of original classical objects, in terms of their technological processes, materials and manual skills. The second was based on protecting the original model while adapting it to new customs or cultural and industrial requirements. The third referred to traditional objects whose notions of the past might stimulate new ideas through memory as a reservoir to encourage innovation.

The second axis introduced by Ugo La Pietra was that of "project and territory" exhibitions. These would highlight techniques and materials connected with regions or places, with the advantage of involving a network that comprised savoir faire, techniques and knowledge of materials used by craftspeople throughout Italy. These exhibitions also successfully established nationwide contacts with craft federations and associations, forming a network that was later also extended overseas. By selecting artists, designers or architects and enabling them to collaborate with craft-based firms, Abitare il Tempo offered the latter an appreciable mediation with manufacturers and an interesting exchange of know-how. But it also engendered an extension of the cultural effect within the enterprises themselves and a greater concentration on specific products.

To achieve this, Carlo Amadori adopted a policy of selective high quality. He did not rent space to just any exhibitor. Each had to be carefully picked, after participating by invitation or selection. This is what sets Abitare il Tempo apart from other trade fairs.

Commercially, more than 50 per cent of market demand is for "period furniture", which has sunk so low that its improvement is a matter of serious concern. What applies to the selection of "good design" also applies to that of "period furniture", with "good" furniture accounting for 10 per cent of output. So what about the other 90 per cent? Is it all just "bad taste"? By treating the theory of "intermediate culture" as a source to be reappraised, Abitare il Tempo has helped to appreciate what official and orthodox criticism would have prohibited.

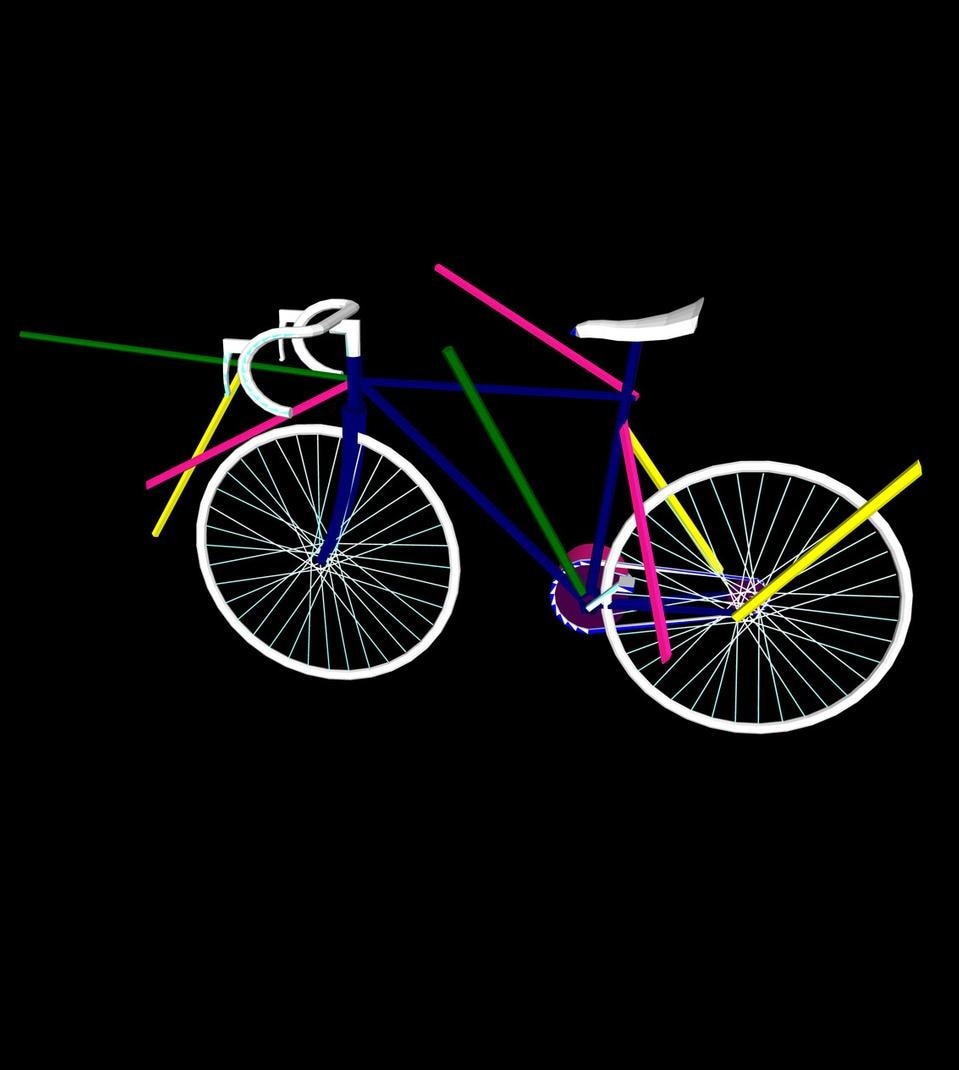

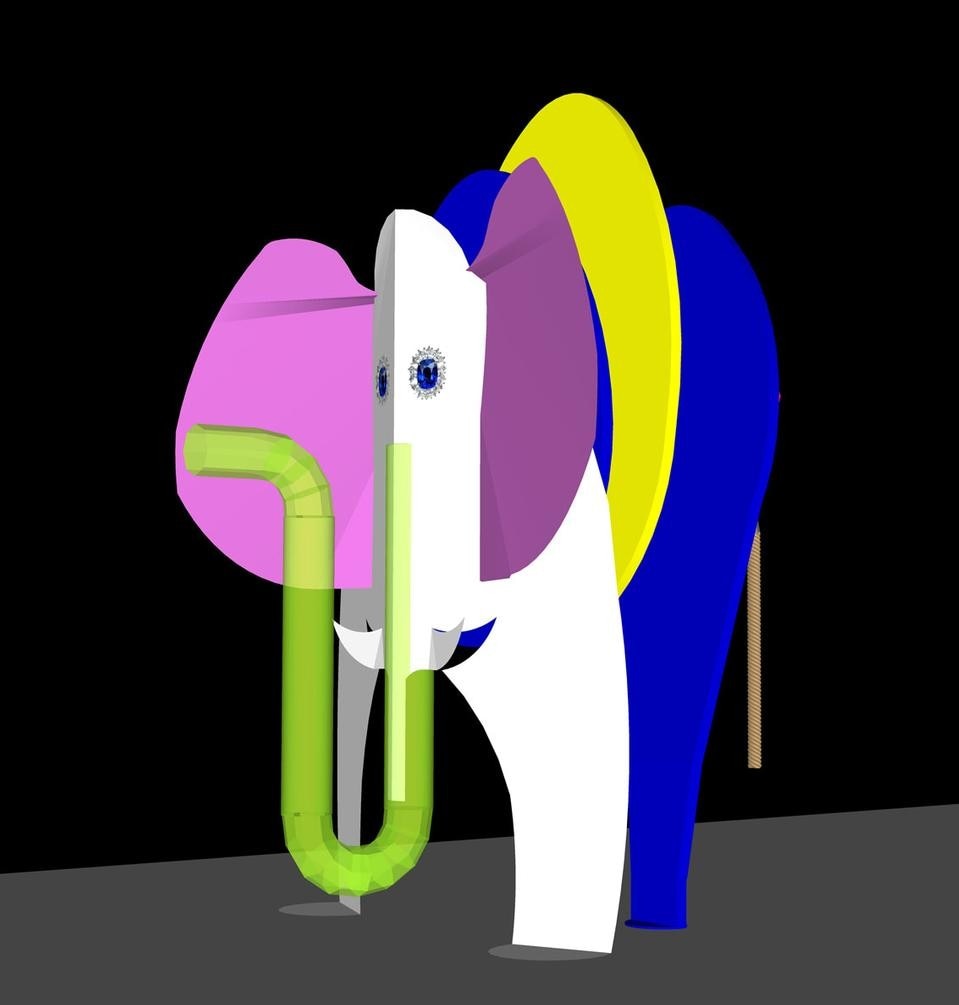

That difference, arising from the interconnecting of classical and contemporary, is a sort of eclecticism that has always distinguished Abitare il Tempo. Indeed, the long list of designers and architects involved includes top names from the widest variety of tendencies. Recent years have witnessed a cultural spread of "metadesign workshops", aimed not only at proposing prototypes of living, but also at policies and situations relating to distribution and markets.

The fair has developed from its four original pavilions to today's eight, with the advantage of being able to accommodate manufacturers of accessories and objects relating to every function of private and public living. As a result, there has been a wider spread of themes and a loss of centrality, due not only to generational change and adaptation to the demands of a globalised market, but also to the lack of interconnection between the sector and technological development.

The fair's 25 years have witnessed the creation of many objects and furnishings through the mediation service provided to companies. These pieces will eventually be gathered together and exhibited at the MoMA in spaces to be transformed by Mario Botta in the Fabbrica del Ghiaccio. This highlights just how important Abitare il Tempo's contribution has been to the furniture sector, through its role and influence on production and contemporary lifestyles.