‘If you go to department store to look at home appliances it’s not like with furniture, where you could probably find ten nice chairs. You’re lucky if you find something 20 years old. It’s a market almost untouched by design’.

The household appliances designed by Jasper Morrison are coming onto the market after three years of work for Rowenta, the German brand that was established in 1884 and entered the fold of the French Groupe SEB toward the end of the 1980s. After the partial takeover of Moulinex and Krups in 2002, the French multinational company is today the world marker leader in small household electrical appliances.

‘It’s an interesting challenge to work on this kind of product’, says Morrison. ‘It’s an unusual area of work for me, as I think it is for most designers, because it’s a sector where design is almost enslaved to the laws of marketing’.

After the dramatic 2001 failure of Moulinex (which dragged Krups with it) and its acquisition by Groupe SEB, the changed managerial direction set out a new design strategy for its eight brand names (Rowenta, Tefal, Moulinex, Krups, Arno, Calor, SEB and Samurai). Instead of limiting project decisions to internally integrated offices, it decided to open up the process and approach outside designers, planners able to escape the laws of so-called advanced systems by using their visionary freedom.

Apart from Jasper Morrison’s involvement with Rowenta, George Sowden and Sebastian Bergne are working on the new projects for Moulinex, while Konstantin Grcic is occupied with Krups. In the meantime, Marc Newson has been the first to come out on the market with of a series of Tefal saucepans, which have already received recognition from the Design Museum of London. The ideal aspired to by Frédéric Beuvry – the head of Groupe SEB Corporate Design – is in tune with industrial design’s most classic tradition: the establishment of an ongoing relationship between a designer and company on long-term projects involving corporate strategies and market positioning. In recent years, excessive marketing has resulted in the codification of the entire repertoire of forms of consumption and the response to a series of needs with a flood of novel objects.

This excess has generated a state of confusion in the consumer, who, confronted by the hyper-determination of supply, is often seen to make a non-choice based exclusively on the lowest price. ‘Especially today, after doing this project, I can really appreciate how incredible Dieter Rams was doing that job for Braun’, says Morrison. ‘It takes so much concentration and labour, but most of all you need power over everybody to make sure your vision arrives in the shop. I think each product should take on the basic shape of its function and nothing more. I looked for a base form for each piece that might gracefully express what it does‘.

In industrial production over the last 20 years (perhaps as a side effect of design’s expressive exuberance in the 1980s), one might say that extraneous characteristics have been standardized to the reality of the object – those that belong to the sphere of personalization and formal connotation but do not determine a substantial variation in meaning. Store shelves are thus crowded with appliances so dominated by their accessory features (colour, details of form, graphic elements) that their real functions seem to be alibis rather than actual necessities.

In this situation, the perfectionism of Morrison’s design language must compete with the demands of an industrial-scale production system plunged into crisis by market expansion and worldwide competition, forced to play the card of design (and therefore quality) to save itself from a contest based simply on the pursuit of the lowest price. It is a suicidal pursuit in a context (such as Europe) in which average labour costs are 20 times greater than in China, where the cost of a working day in an average small electrical-appliance factory comes to around $1.10.

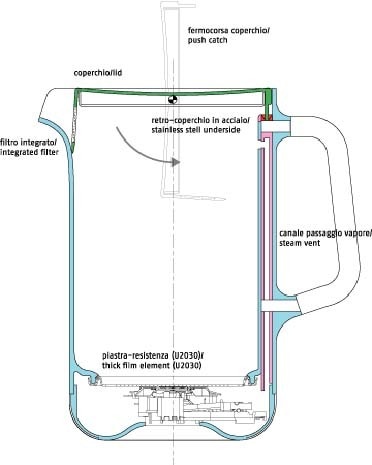

In his series of small electrical appliances for Rowenta, Morrison (assisted by John Tree, who followed the project for three years) expresses his vision of a world inhabited by silent presences; mysteriously normal, elegantly discreet and non-intrusive, they seem disinterested in the human world. It is almost as though they are evidence of a parallel universe brought onto the scene by the unperturbed and idealistic sensitivity of their creator.

In fact, Morrison appears to look at the things around him with a strange benevolence, attracted by the special spirit radiating from objects that seem to have prevailed over the ambitions of their makers. It is perhaps to avoid the danger of an overabundance of signs in the formal process that Morrison seems to require a meticulous and detailed process of fine-tuning – everything plays on subtle differences of angles and millimetres, radii of curvature, proportions between parts and dimensional ratios. This practice is possibly useful in giving way to a kind of automatic writing that ‘objectively’ helps him give full expression to the nature of the forms. It is a way of bringing out what Morrison refers to as ‘objectuality’, or the ‘object’s personality’, thus setting up ‘the same relationships that we establish with human beings’: a kind of kinship.