For four years, there has been more than one reason to stop off at Saint-Étienne, around an hours drive from Lyons going in a south westerly direction. As well as the international design biennial organised since 1998 by the local school of fine arts, many ideas on the boil. The French town has fulfilled its ambition – to transform itself from ancient mining centre (an activity abandoned in 1975 and which certainly hasn’t contributed to making it attractive from an architectural or tourist point of view) into a design hub. It is the dream of mayor Michel Thiollière: “Saint-Étienne could be for design what Avignon is for theatre or Arles for photography”, he explains. The highlight is the future International Design Centre, due to open by 2005 on the site of the ex Giat factories (Giat stands for Groupement industriel des Armements Terrestres, the ex site of the Manufacture royale d’armes, created in 1764 and rebuilt in 1866). Eighteen hectares, the conversion of which will be the subject of an international competition.

A truly international biennial

A typical day at the design biennial – nine days of exhibitions, workshops, fashion shows, conferences and lots of events “off circuit” – moves to a tight schedule. The official reopening of the building site (interrupted years ago) of the church by Le Corbusier for Firminy-vert in the morning, at midday the opening of the exhibition “Design de Mode” at the museum of applied art, reopened recently following redesign by Jean-Michel Wilmotte or, alternatively a retrospective on design from the last twenty years at the Museum of Modern Art. In the afternoon, a tour of the projects and designs proposed by designers, manufacturers and students from around a hundred countries and crammed into 40 000 square metres of exhibition space filled with young people who take notes in sketch books. All very international, from the chaise longue by French designer Eric Jourdan to the collection of objects for everyday use by Nicolas Cissé from Senegal, lamps in fabric from Madagascar designed by Zoarinivo Razakaratrimo and the creations of ten designers from northern Europe (including Iceland): “This year what is different form the last edition is that I chose just women” explains curator Pascale Cottard-Olsson, “to demonstrate that design isn’t just for men”.

Workshops – what’s brewing

Worth a mention apart are the workshops, around twenty working groups made up of students, designers and professors of different nationalities getting together to work on different themes. A range of witty proposals can be found in “Design for Europe” directed by Jörg Adam & Dominik Harborth, where each participant was asked to design a map of Europe, a characteristic object, a new flag and packaging; in Masayo Ave’s sensory space each person can experiment with the “sound” of materials. “My approach is to transform the particular emotional quality of a material into an item which will be useful in contemporary society”, explains the Japanese designer. Encouraging forms of African creativity and their development with local materials and techniques was instead the objective of Kossi Assou (Togo). The starting point was the simple and daily gesture of sitting down to eat. Despite the fact that eighty percent of Senegalese houses have western furniture, most of the inhabitants continue to sit on a mat and eat with their hands. “How can tradition be adapted to contemporary life?” was the question posed to the participants.

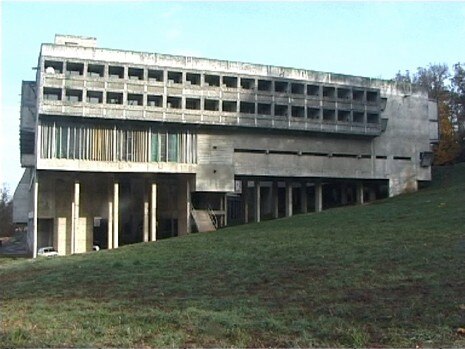

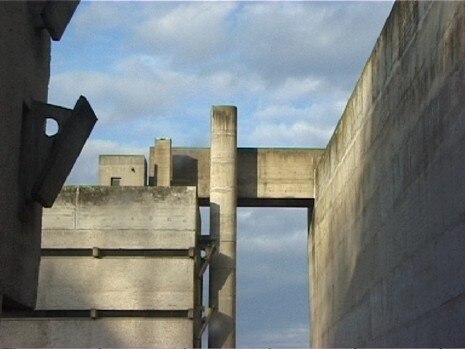

A night in the convent

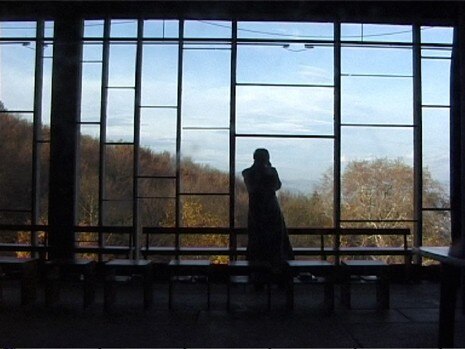

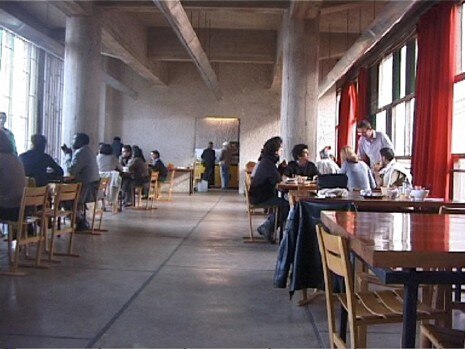

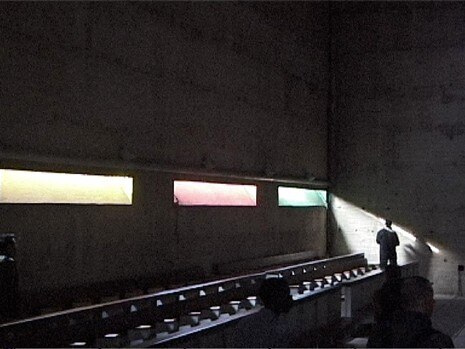

The evening, moving on to Eveux for dinner and a night at the convent of Sainte Marie de La Tourette. Le Corbusier again, in this case with one on his most significant European works, opened 19 October in 1960 and built for Dominican monks. On arrival you are allocated a cell – just 1.83 metres wide, 5.92 long and 2.26 high but – modulor docet – a perfect fit. Each cell also has a balcony from which to look outside but positioned in such a way that no one can see in. “Architecture is the sum of space, volumes and light” as Le Corbusier often said and moving round the corridors and communal areas of the monastery you can immediately see why. Everything here comes down to the question of light. The materials, building methods and finishes are simple and humble as imposed by the Dominican order but everything is extremely functional. Such as the neon light which illuminates the corner at the foot of the staircase at each floor, interrupting the wall in a very fragile moment – a very simple as well as very elegant solution. Or the absence of window frames, the glass sits directly on the concrete wall, held in place by just a thin layer of mastic. The view onto the countryside around is breathtaking, spectacular too is the church, dominated by light, primary colours, geometry and a height which takes ones breath away. The enthusiasm which can be perceived in the words of the priest who takes us on a quick tour (“When I came hear five years ago I didn’t know anything about modern architecture and I didn’t even know who Le Corbusier was…Today I call him Charles-Eduard”,) explains effectively the feelings of those who live in the convent. A deep relationship, of affection and gratitude bonds the monks to the architect who has designed the building, to the point that when Le Corbusier died, his body was brought to La Tourette and laid there for a night before being buried. Forty years on, the building is standing up for itself. And weathering quite well one might say considering that noone has touched it since then. The monks have launched an appeal however and in 2003 restoration and maintenance work should start.

16-24.11.2002

3rd International Biennial Design Festival Saint-Étienne 2002 http://www.institutdesign.com/bien/home.htm

http://www.mairie-st-etienne.fr

Dominican monastery of Sainte-Marie de La Tourette

http://www.couventlatourette.com